Porcelain For Sale: A HISTORY OF THE LOSSES OF THE STATE MUSEUM OF CERAMICS IN THE 1920s AND 1930s

The campaign to export art treasures initiated by the Soviet government in the 1920s and 1930s affected numerous Russian museums. The State Museum of Ceramics was one of them, with many of its valuable exhibits donated to Antikvariat, the public agency responsible for the sale of art and antiques abroad. A review of the museum’s archive documents has helped restore the chronology of events of those times, estimate the scope of losses and study the composition of the items offered for sale.

“Spring” sculptural group. Germany, Frankenthal. 18th century

From the late 1920s onward, the museum collections of the Soviet Union were hostage to the forced industrialisation initiated by a government facing acute shortage of gold and currency reserves. The development of industry demanded ready sources of financing, with the export of antiques and art treasures becoming one of them.

In 1928, after review of the first draft five-year plan and a number of decrees from the Council of People’s Commissars,[1] the expropriation and sale of museum exhibits became systematic and gained momentum. As experience showed, the mass export of cultural heritage, which resulted in irretrievable losses of priceless masterpieces, was not effective and did not justify expectations. Meanwhile, the Bolshevik economic policy proved a trial for Russian museums forced to cooperate with Gostorg[2] and Antikvariat[3]. The State Museum of Ceramics at Kuskovo (hereinafter, the SMC) was no exception.[4] To date, the tempestuous events of those years have been uncharted pages in the history of the museum. This article serves as the first attempt to fill that gap and provide an estimate of the losses.

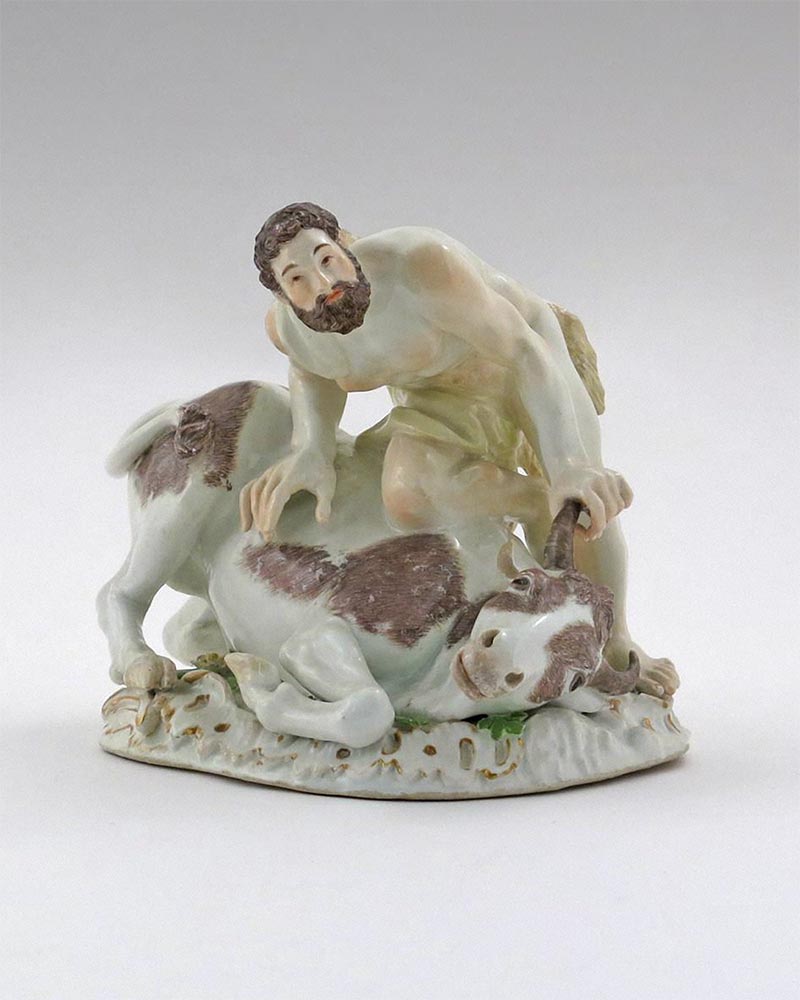

“Hercules Capturing the Cretan Bull” sculpture.

Germany, Meissen Porcelain Manufactory. 1740s-1760s

The fate of numerous porcelain items from the SMC was decided by two documents. The first was the agreement concluded on February 15, 1928, between Mosgostorg[5] and Glavnauka of the People's Commissariat of Education[6] clearly defining a common objective: to maximise the export of art treasures and antiques. According to the agreement, Mosgostorg undertook to expand market channels and sell the items on beneficial terms, while Glavnauka was responsible for increasing the number of treasures available for export “both by selecting and assembling collections and lots of interest to international buyers, and by sourcing new objects that may be withdrawn from museum collections.”[7] The museum also received an Instruction on Identification and Selection of Artworks and Antiques of Export Quality. The document established the selection principle, according to which the objects that were “most precious in terms of material and quality/artistic, historic, etc.”[8] should be the first to be put forward. In addition, special authority was allocated to representatives of the People’s Commissariat, specifically “the right to examine all the museum’s current collections and diverse repositories.”[9]

Based on these documents, on May 16, 1928, the Porcelain Museum handed the first 1,265 objects to Mosgostorg for sale. Valuation was carried out by a committee that included members of Glavnauka and Mosgostorg, along with staff from the Porcelain Museum. The selected objects were stored in a special museum room, which was sealed by Mosgortorg after the contents had been inventoried. Interestingly, a small number of these objects were chosen for auction in London, and the museum’s director Sergei Mograchev received explicit instructions in this regard: “The boxes should bear the inscription ‘Fragile’ in German and English, a label and the address: Bank for Russian Trade Ltd.,[10] London.”[11] A customs official was invited to the museum to speed up the shipment of the “goods” and supervise packing. The quality of the future auction lots fit perfectly the requirements outlined above: a Meissen tea and coffee service with floral painting in a leather case (1750-60s, 31 items), part of a Sevres dessert service with gilt chinoiserie decoration (19th century, 36 items), a Crown Derby tea service (late 18th century, 17 items), a Meissen group entitled “Bull Baiting” (“Bison Hunting”) from the mid 18th century, from a model by Kandler, as well as numerous Sevres plates and cups (18th century) - in total, 127 rare porcelain objects from the great manufacturers of Europe.

The rest of the treasures appropriated from the museum were transported to the Mosgostorg store at 26, Tverskaya Ulitsa. The list of these objects is replete with pieces of equal interest, such as a cobalt Dart service (early 19th century) with views of Paris and its suburbs, part of a Meissen dinner service with bird images dating to the Marcolini period, part of a rare service with images of French farmers and folk characters manufactured by Denuelle, rue de Crussol, in the 1830s, various Sevres decorative plates (18th century), and a variety of items from the Vienna, Berlin, Ludwigsburg and Paris manufactories (18th-early 19th centuries).

Pieces from services with Chinese scenes in the style of J.G. Herold. Germany, Meissen Porcelain Manufactory. 1723-1730

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

The following year was without losses, but 1930 bore witness to two submissions to Antikvariat, the agency of the People's Commissariat of Foreign Trade responsible for selecting works to be sold abroad.[12] Unsurprisingly, the focus was on top-quality Meissen items dating to the first half of the 18th century.[13] Apart from European porcelain works, the list of items of “indisputable” export quality included French tapestries, Venetian glass and European bronze, Chinese porcelain vases and Canton enamel plates.[14]

According to SMC records, from 1928 to 1931, the most serious losses concerned European porcelain from the main museum collection. This period saw numerous rare items withdrawn from the museum and the loss of first-class works worthy of the best collections in the world. Meissen items included early samples of the factory’s work with Chinese scenes in the style of Johann Herold from the 1720s and a tea and coffee service with an embossed flower pattern and the image of a horseback rider from about 1730; items from the unique Zubalov service, decorated with paintings of fantastical animals by Adam Friedrich von Lowenfinck in the 1730s; plates with genre scenes painted in Friedrich Elias Meyer’s studio in about 1747 (rare Meissen objects decorated by hausmalers); and china from the 1730s and 1740s, decorated in traditional Far-Eastern styles, including pieces from a service in the Japanese Kakiemon style service items plates painted in the style of Imari ware. Among the well-known Sevres items to be taken were pieces from the Arabesque and Shuvalov services dating from the late 18th century.

Тарелки из столового сервиза с изображением птиц. Германия, Мейсенская фарфоровая мануфактура. Конец XVIII – начало XIX века.

Музей керамики, Музей-усадьба «Кусково»

In addition to crockery, valuable porcelain figures from the 18th century were also lost. These included the Meissen sculptural groups “Persian with Moor on Elephant” and “Hercules Capturing the Cretan Bull” based on models by Kandler, rare Harlequin and Scaramouche figures from the Commedia Dell'arte series based on models by Wenzel Neu from the Kloster Veilsdorf manufactory), “Spring” allegorical group from the Frankenthal factory, and the sculptural composition “Knight and Lady at a Dressing Table” from the Royal Vienna Porcelain Manufactory.

Later-period porcelain was also ceded. The items dating from the 19th and early 20th centuries were not priced as highly, but many of them were of value to the SMC collection. These include a five-item dejeuner with the monogram of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, manufactured by Carl Tielsch & Co in Altwasser, a series of 12 bisque Apostle figures from the Royal Porcelain Factory in Copenhagen, and a nine-item tete-a-tete service with the Oranienbaum town crest manufactured by the Imperial Porcelain Manufactory in the reign of Nicholas I.

The selection of objects for sale reached its peak in 1932-1933, when withdrawals occurred on a monthly basis (12 in 1932, 13 in 1933). Furthermore, a large number of porcelain items were taken from the museum’s reserves. Most often, the rare objects made their way to Mostorg Consignment Shop No. 92, where one female employee had a power of attorney to “receive goods from the Museum of Ceramics”. More than once, objects were given to Torgsin Store No. 1[15]: this “closed” store received china and glassware from predominantly European factories.

Although in the first stage of the process the majority of withdrawals were of foreign porcelain destined for export, the situation changed in 1932. The bulk of items lost in 1932-1934 comprised Russian works (predominantly from private factories). Figures, crockery and household items from various periods and of various levels of quality were selected for domestic sale. Of all the wide thematic variety of Russian porcelain held by the museum, two categories that were in high demanded among the officers of the trade agencies were nude figures and miniature figurines from the Popov and Gardner factories. Notably, Gardner nude figures of the mid 19th century were valued higher than figurines from the same factory dating from the 18th century.

“Persian with Moor on Elephant” sculptural group. Germany, Meissen Porcelain Manufactory. 1740s-1760s

The State Museum of Ceramics had always been distinguished by its diverse collection of Russian porcelain figures, with several examples of numerous models available. In a certain sense, this circumstance saved the collection, although numerous duplicate copies provided for sale were of the utmost interest to experts. However, although the SMC employees tried to only cede duplicates, the loss of extremely rare works could not be avoided. These included painted terracotta figures “The Bather” and “Negro Playing the Double Bass” (1860s and 1870s) from the Guzhev factory, “Pony”, “Hare” and “Boy with Flute” miniatures from the Imperial Porcelain Manufactory (1820-1840s), and a figure of Nicholas I from the Sipyagin factory (mid 19th century).

The origin of the items that were withdrawn deserves special attention. The noteworthy provenance of many of them was due to the specific nature of the Museum of Ceramics’ collection, based on large private collections and acquisitions from the former imperial residences. Thus, the best Sevres and Meissen porcelain items selected by Antikvariat for sale originated from the famous collections of Leo Zubalov and Dmitry Shchukin and others had arrived from the Hermitage and the Yusupov Palace. The items from Danish factories belonging to Empress Maria Feodorovna were expropriated by Gosfond as “unnecessary to the museum and having no museum value”.[16] Works came from collections of well- known Moscow antiquarians including Vladimir Girshman, Sergei Bakhrushin, Mikhail Ryabushinsky, Osip Tseytlin and Claude Giraud. The same fate struck the seminal Russian porcelain collection of Aleksei Morozov amounting to about 2,600 items. This extraordinary collection, which had laid the foundation of Museum of Ceramics, lost some 300 items from Russian factories, including several unique works.

The procedure for the valuation of items was unclear and had several stages. We know that the People’s Commissariat of Trade established a general plan for the sale of antiques, based on which the People’s Commissariat for Education allocated the sums in the plan among the museums. Museum employees carried out the selection and primary assessment of the items. As the allocations for the museums were based on total value rather than on the number of items, the museum employees were incentivised to value the exhibits as highly as possible (and, therefore, withdraw fewer items). Assessment and secondary evaluation of the items selected, as well as further approval of the lists, was to be carried out by an expert committee of Glavnauka, the Main Directorate of Scientific, Artistic and Museum Institutions. Antikvariat, in its turn, made its own assessment, trying to undervalue the items and thus obtain more of them. The final sale price was generally reached by negotiation between the museums and Antikvariat. Notably, the price was also affected by the global situation, particularly the economic crisis of 1929-1933, which resulted in a fall in prices for artworks.[17] When sales plans were drafted, the relevant sums were specified individually for each category of “item” (that is, pictures, engravings, books, tapestries, furniture, gold/silver, icons/iconostasis, bronze/chandeliers). As for porcelain and glassware, an abstract from the draft plan of All-Union Export Association Antikvariat for 1930/1931 states the expected sales proceeds:

Porcelain, glassware and stained-glass artworks 250 thousand rub.

| LEPKE auction in September-October c.y. | 80.000 rub. |

| Small auctions in Germany | 10.000 rub. |

| in Austria via Gluckselig | 30.000 rub. |

| in America via IMANTIK | 20.000 rub. |

|

in France via antique sellers (including Russian porcelain) |

30.000 rub. |

|

in Germany directly to companies (including for department stores) |

25.000 rub. |

| In England via ARCOS | 30.000 rub. |

| In the USSR | 25.000 rub. |

ALL DISPUTED items should be obtained for implementation of the plan.

Russian State Archive of the Economy. F.5240, Inv.18, D.1576, P.76

The art treasure withdrawal process itself was implemented by people with varying qualifications and opinions. In addition to party officials far from museum affairs, it involved prominent specialists and art connoisseurs. The SMC statement dated July 13, 1930, mentions a “Troynitsky”[18] as part of Special Shock Brigade selecting the items for Antikvariat. As well-known experts were engaged in the shock brigades, this most probably refers to Sergei Troynitsky, a famous art historian and armorist, an authority on porcelain and the first post-Revolutionary director of the Hermitage (from 1918 until 1927).[19] In 1928, he was appointed a representative of People’s Commissariat for Education authorised to select items for export, and he was the member of the valuation committee of the Leningrad office of An- tikvariat. Incidentally, after his arrest and exile to Ufa, he made his way back to Kuskovo and worked there as an SMC researcher until his death.[20] The abovementioned brigade also included Vladimir Klein, professor, guru of Russian antiquities, the first head of the State Historical Museum fabric and costume department (from 1922), and deputy research director of the Kremlin Armory (from 1929). Also worth mentioning is Vladimir Eifert, an artist and museologist who, over the years, worked as academic secretary of the Tretyakov Gallery, deputy director of the Museum of Modern Western Art and an antiques expert in the USSR’s trade delegations in Berlin, Paris and Stockholm. Klein and Eifert were also mentioned in archive documents of the People’s Commissariat for Trade, specifically in the “list of staff and members of the brigade appointed for the identification and selection of museum valuables of export quality.”[21] According to the documents, the SMC items selected by them were handed to Antikvariat agent A.I. Tsvetayev. Most probably, this was Andrei Ivanovich Tsvetayev, the son of the founder of the Museum of Fine Arts. Trained as a lawyer, in the Soviet Union, he cooperated with Gostorg as an expert on painting and porcelain.

Mikhail Kristi, deputy director of the People’s Commissariat for Education’s Glavnauka (1926-1928)[22], was also an interesting personality. His name was specified in the Instruction above as “People’s Commissariat for Education representative authorised to select export items from museums.” Superbly educated, a former publisher and editor of progressive newspapers, in the early days of the Soviet Union, he succeeded in the preservation and renovation of Petrograd’s scientific institutions. His organisational skill and talent for leadership were also in evidence in his work in museums and, after two years working in Glavnauka, he was appointed director of the Tretyakov Gallery (1928-1937).[23] Interestingly, among the names given in the museum records, we can find several well-known pre-Revolutionary Moscow antiquarians. For example, Nikolai Nosov, an employee of Moscow’s Gostorg, came from a famous dynasty of industrialists and was a connoisseur of the applied arts. The bulk of porcelain and glass items from his collection was donated in 1923 to the Porcelain Museum[24] (and is still owned by the SMC). Paradoxically, it was Nosov who was authorised by Mosgostorg to collect the museum works withdrawn in 1928 for a London auction.

Notably, the institutions headed by the people mentioned above pursued various objectives in their cooperation. With regard to the selection and valuation of museum works, the opinions of Glavnauka were frequently in opposition to the judgments of Gostorg and Antikvariat. This was mirrored at a higher level by the opposition of the two People’s Commissariats, with both parties advocating their interests. Presumably, the Museum of Ceramics was also the object of this war between “dealers” and “educationists”.

The SMC records of this period do not reflect all the nuances of events. However, they do underline the main outcome, that is, the loss of thousands of exhibits dispersed nationally and globally. The results of the campaign are revealed by the figures: in 1928-1934, the main and reserve collections of the museum lost more than 6,600 items worth a total of 269,000 rubles.[25] (According to the documents, the SMC collection amounted to 21,170 items as of October 1, 1929).[26] Undoubtedly, the scope of these withdrawals is just a drop in the ocean when set against the requesitioning of art treasures all across the country. However, for the specialised Museum of Ceramics this figure was highly significant. The records evidence that the massive art object withdrawal process affected the SMC profoundly, and many of its exhibits, along with treasures from the main museum collections of the USSR, were forced to play a role in the country’s industrialisation. Today, the numerous withdrawals documents of that period are not only records of their time, they also represent an important source of evidence concerning one of the most dramatic periods in museum history of the 20th century.

- In 1928, two decrees of the USSR’s Council of People’s Commissars were enacted: “On efforts to increase export and sale of antiques and artworks abroad” dated January 23, 1928, and “On identification and export of antiques” dated July 24, 1928.

- State Export and Import Agency (Gostorg).

- Main (from autumn 1929, All-Union) State Trade Agency for Buying and Selling Antiques.

- In 1929, the State Porcelain Museum was renamed the State Museum of Ceramics. In 1932, it was transferred to Kuskovo near Moscow.

- Moscow branch of RSFSR Gostorg.

- Main Directorate for Scientific, Artistic, and Museum Institutions of the RSFSR People’s Commissariat for Education (1921-1930); from 1930, transformed into the RSFSR People’s Commissariat for Education Scientific Sector.

- Archives of the SMC Records Department. Documents of 1928. Case “Withdrawal Records, 1928”, sheet 24.

- Ibid. Sheet 23-23 overleaf.

- Ibid. Sheet 23.

- The Bank for Russian Trade operated in London in 1923-1932 and acted as the financial authority of Soviet Party institutions.

- Archives of SMC Records Department. Documents of 1928. Case “Withdrawal Records, 1928”, sheet 26 overleaf.

- “Antikvariat” was founded in 1928 under the control of the RSFSR Gostorg. In 1929, it was taken over by the People's Commissariat of Foreign Trade. Quoted from: E. Osokina, “Antikvariat (On the Export of Art Treasures in the Years of the First Five-Year Plan)” [“Antikvariat (Ob eksporte khudozhestvennykh tsennostey v gody pervoy pyatiletki)”] in: Economic History Yearbook 2002, (Moscow, 2003).

- Archives of the SMC Records Department. Documents of 19291930. Case “Withdrawal Records, 1930”, sheet 54 (Document No. 29 dated July 13, 1930).

- Ibid. Sheets 63-63 overleaf. (Document No. 31 dated August 12, 1930).

- The Torgsin (“Trade with Foreigners”) trade agency was opened on July 18, 1930, and on January 4, 1931, was reformed into the AllUnion Association for Foreign Trade in the USSR. Closed on February 1, 1936. Quoted from: E. Osokina, Gold for Industrialisation: Torgsin [Zoloto dlya industrializatsii: Torgsin], Moscow, 2009).

- Archives of the SMC Records Department. Documents of 19311933. Case “Withdrawal Records, 1933”, sheets 30-31 (Document No. 1 dated September 5, 1933); Withdrawal Records, 1934-1935. Case “Withdrawal Records, 1934”, sheet 1 (Document No. 1 dated February 2, 1934).

- The author would like to thank E. Osokina, Doctor of Historical Sciences, for consultation on this matter.

- Archives of the SMC Records Department. Documents of 19291930. Case “Withdrawal Records, 1930”, sheet 54 (Document No. 29 dated July 13, 1930).

- The SMC withdrawal records also mention a namesake, F. Troynitsky, former inspector of the Gosfond Lenin Region Financial Department.

- SMC records do not specify the exact date of S. Troynitsky joining Kuskovo. Based on the year of his detention (1935) and a three-year period of exile, he is assumed to have arrived in Moscow in about 1939.

- Russian State Archives of Economics, fund 5240, file 18, item 1576, sheet 197.

- The name of М. Kristi was also associated with donation of several valuable Soviet porcelain objects to the Museum of Ceramics: in 1929, the museum purchased his “Hunger” and “Awakening East” based on the models of N. Danko (FR 9704, the second figure did not survive) and two cups and saucers with Suprematist painting based on designs by N. Suyetin (FR 10939/1-2, 10694/1-2).

- Quoted from: Ye. Gladysheva, “М. Kristi, Director of the Tretyakov Gallery” [“M.P. Kristi - Direktor Tretyakovskoy galerei”] in: Tretyakov Readings 2013: Notes from a Scientific Conference, (Moscow, 2014), pp. 277-290.

- Quoted from: V. Mikitina, “Cultural Achievements of the Russian Revolution of October 1917” [“Kul- turnye zavoevaniya Oktyabrya”]. First Proletarian Museum in Moscow, in: The Museum and The Russian Revolution of October 1917: The Fate of People, Collections, Buildings [Muzey i revolyutsiya 1917goda v Rossii: sud'ba lyudey, kollektsiy, zdaniy], (Yekaterinburg, 2017), p. 133.

- The exact figure cannot be estimated due to the poor preservation of several documents.

- Archives of the SMC Records Department. Documents of 19291930. Case “The Collection of the State Museum of Ceramics as of October 1, 1929”, pp. 3-4.

See also:

Tamara Shubina

Tamara Shubina

The Gorki Estate and Its Collection

Darya Tarligina

Darya Tarligina

ENGLISH POTTERY IN RUSSIA. In the 18th and 19th Centuries

Zhanna Polansky

Zhanna Polansky

The "Ballets Russes" in lacework porcelain from the Thuringia factories

Marina Vaizey

Marina Vaizey

Science into Art, Art into Science

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Museum of Ceramics, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Photo

Photo

Archive of Records Department, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Archive of Records Department, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Archive of Records Department, Kuskovo Memorial Estate

Photo

Photo