The "Ballets Russes" in lacework porcelain from the Thuringia factories

From the first factory production of porcelain figurines in Europe, ballet has been a favourite motif: porcelain is a perfect vehicle for conveying the dynamism, brightness of colour, and elaborateness of pose and gesture that is characteristic of the art form. Towards the end of the 19th century certain standard images of the ballerina began to develop, complete with indispensable attributes such as formal stage costume, the puffy tutu and pointe slippers. Its imagery became popular and continues to be drawn on by porcelain makers to this day.

Lacework Porcelain

In the 20th century, ballet dancers depicted in role became a popular subject for porcelain manufacturers. Wide-ranging in its choice of themes, the European porcelain figurine industry, over the centuries in which this form of applied art has existed, has embodied some of the most fashionable and progressive trends in art.

Sculptural composition of Columbine in the ballet “Carnaval”

From the “Ballets Russes” series. Porcelain Manufactory Aelteste Volkstedter Porzellanfabrik AG Germany, Thuringia, 1912-1945

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding Height - 28 cm. Private collection, Moscow

In the work of the best porcelain artists the steps (pas) and pirouettes of dance are conveyed with a good degree of accuracy, essentially as they would appear in a ballet class or performance. However, factories that were less interested in such high artistic quality also manufactured mass-market items that were “themed" or “based on" such subjects, and the poses and movement of these porcelain dancers have little in common with reality. Instead, the aim is to “evoke" dance elements, to represent ballet poses in a generalized form, in a manner intended to fire the imagination: no dancer could ever perform such fanciful elements in dance - to do so would actually be physically impossible. Nevertheless, a great many such ballet “fantasies" have been manufactured by porcelain makers who have proved less than scrupulous in their approach. Their figurines are distinguished by a sense of grace that, though artificial, can certainly be attractive, and the result has proved immensely popular with the public.

True artists in porcelain, however, rather than catering for such undemanding tastes, were determined to maintain the reputations of their manufactories and began to use photography (which gradually replaced engravings and prints) as a source for the images of such ballet figurines. These were not photographs taken by amateurs during performance, but rather the work of professionals, who usually went through dozens, even hundreds of shots to select the one best for reproduction. Such photographic sessions were specially staged, properly lit and set against an appropriately arranged background, one that would display the dancer at the best possible angle in the quiet working environment of the studio. Such high-quality photographs of ballet dancers were published in newspapers and magazines, as well as on postcards, which were eagerly collected by ballet connoisseurs and aficionados, especially when they depicted the most acclaimed performers of the day in their most celebrated productions.

Following weeks of advance promotion, Sergei Di- aghilev opened the first Paris season of his “Ballets Russes" on May 19 1909, dazzling audiences with the bright costumes and sets of his productions, as well as the absolutely new works of ballet themselves. These pieces were directed by the young choreographer Mikhail Fokine, complemented by marvellous costumes and sets created by Leon Bakst and other artists, and by innovative music that enhanced the whole theatrical experience. But it was the stars who really won over those first Paris audiences: Vaslav Nijinsky with his phenomenal virtuosity, Anna Pavlova with her lightness and grace, Tamara Karsavina with her refined, sensual beauty. For Parisians, Diaghilev's company were an ideal combination of the lyric and the exotic: they enjoyed enormous success over the four weeks of their first season.

Diaghilev's second Paris season, a year later, proved even more successful; its hit was Fokine's third ballet in the company's new repertoire, “The Firebird", set to the music of the brilliant young Igor Stravinsky. By the following year, 1911, Diaghilev had severed his ties with St. Petersburg, and his “Ballets Russes" became a permanently touring European company which performed with great success in London, Berlin and Monte Carlo as well as Paris.

Such heights of popularity meant that all the principal dancers of Diaghilev's troupe were photographed professionally, their pictures reproduced in great quantities in all sorts of printed forms. The artisans of the porcelain factories had a great variety to choose from and could select episodes whose characteristics were best suited for their craft. Many of the “Ballets Russes" celebrities were represented in porcelain by craftsmen from the Meissen factory, as well from the porcelain factories and workshops of Thuringia and other European facilities. When Diaghilev's company was at the peak of its fame, these included craftsmen working at the Imperial Porcelain Factory in the company's native St. Petersburg: alongside many other items themed around Russian ballet, one particularly notable piece was a 1913 figurine designed by Serafim Sudbinin[1], representing Anna Pavlova as Giselle.

The Thuringia factories were equally absorbed by this fashionable trend. Unlike their colleagues elsewhere, however, the porcelain artists there did not aspire to capture images of particular dancers with documentary accuracy, but were rather more interested in highlighting the costumes of the dancers. Designed by prominent artists, the costumes of Diaghilev's company were works of art in themselves, both in their preparatory sketches and in finished form.

The process for modelling and painting such porcelain statuettes has remained the same throughout the history of this decorative art form: it involves not so much creating or inventing something original as copying, as carefully as possible, works of great art.

The porcelain artists of Thuringia were fortunate in the sense that the costumes of the Diaghilev productions, which left behind the academic simplicity of tutus and pointe slippers, were often elaborate and dazzlingly coloured. The choice of textiles for the dresses of the ballerinas was a perfect match for porcelain: usually made of tulle gathered at the waist, or even ordinary gauze, such costumes were ideally suited for lacework porcelain, the distinctive technology of Thuringia porcelain in which its practitioners were supremely accomplished.

The materials printed at the time about these ballets allows identification of the particular episodes represented in such porcelain figures. Clearly there are certain specific factors in the task of giving volume to two-dimensional images. In most Thuringian porcelain figures, portrait likeness with the dancers concerned was not a priority, although other elements fully correspond to the designs or photographs upon which their creators drew.

In general, both the photographs that inspired the porcelain makers, and the particular dancers performing specific pieces imaged in the pictures, can be fairly easily identified by the wide range of characteristic details that are there both in the porcelain objects and in the photographs concerned. Porcelain figurines, more than any other form of decorative art, can capture such moments of magic and present to the viewer in a snapshot all the subtleties and nuance of the fragment of a ballet piece - its dynamics, colour and volume.

Vaslav Nijinsky

The showmanship and charisma of Vaslav Nijinsky was such that he could change his appearance almost beyond recognition in every different role that he performed. Devoted theatre-goers and ballet-lovers of the early 20th century used to say that it had been at least two or three generations since they had seen anything comparable to Nijinsky's artistry in dance.

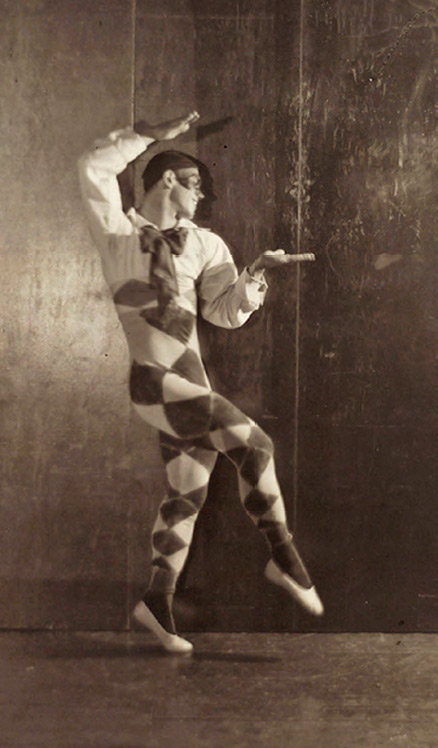

Vaslav Nijinsky as Harlequin from the ballet “Carnaval”. 1910

Photograph by Robert Schumann. Private collection, St. Petersburg

In Fokine's “Carnaval", Nijinsky was the enigmatic Harlequin to Karsavina's Columbine, while in the brutal and erotically charged “Scheherazade" he played the role of the exotic Golden Slave.

As a choreographer, Nijinsky created productions of astonishing variety, whose style of movements and patterns of dance were radically different not only from what the public was accustomed to in ballet, but also from each other.

Rumours about Nijinsky's and Diaghilev's scandalous relationship only boosted the popularity of the “Ballets Russes". When Nijinsky married in 1913, he was dismissed from the company as punishment. During World War I he was brought back briefly for two seasons, but his later mental illness put an end to his astounding career.

Tamara Karsavina

One of the most spectacular stars of the “Ballets Russes", Tamara Karsavina's art impressed artists and poets alike. She was depicted in costume by artists such as Valentin Serov, Bakst, Mikhail Dobuzhinsky, Sergei Sudeikin, Zinaida Serebryakova, John Singer Sargent, Wilfrid Gabriel de Glehn, Alfred Eberling, George Barbier and many others. “The turning point in her artistic evolution was the invitation to join the ‘Ballets Russes'. In the ‘Ballets Russes' she became a ballerina two years earlier than this status was officially granted to her at the Imperial company. In the second season of the ‘Ballets Russes', Karsavina again captivated Parisian audiences. From then on the ballerina divided her time between the Mariinsky Theatre and the ‘Ballets Russes'." (From: “Tamara Karsavina. ‘La Rose de Russie'" by Natalya Dunayeva in the collection “Legendary Actors of St. Petersburg", St. Petersburg, 2004, Russian State Library).

Tamara Karsavina as Columbine from the ballet “Carnaval”. 1910

Postcard. Private collection, St. Petersburg

The porcelain figurine presumably featuring Karsavina as Columbine, produced at one of the Thuringia manufactories, was based on a well-known portrait by Wilfrid Gabriel de Glehn. Compared to de Glehn's image, the costume of the porcelain ballerina looks much more opulent, lacking the elegant simplicity of the portrait image. That is not to say that this “transformation" significantly misrepresented either the ballerina or the character she was performing: such an eye-pleasing porcelain statuette was intended for interior decoration and never aimed for documentary likeness (the face of the porcelain ballerina does not resemble Karsavina's: even the colour of the hair is different). The porcelain figurine is not an image of Tamara Karsavina, the particular “Ballets Russes" star, but rather that of an abstract ballerina in performance.

The Thuringia porcelain artists never intended to create thorough, faithful copies of the images that they took from paintings or photographs, instead they had their own distinctive interpretation of the characters that they were modelling. Any figurine or statuette produced at the porcelain manufactories of Thuringia had to have the trademark features of Thuringia porcelain, such as copious use of gold in colouring and lacework porcelain. This opulent exterior of porcelain statuettes was of paramount importance: the rules of applied art are fundamental and distinctive.

Karsavina's performances inspired Russian porcelain artists as well, such as the porcelain group designed by Serafim Sudbinin that featured Karsavina as the Firebird in Stravinsky's ballet of the same name, produced at the Imperial Porcelain Factory in 1913. Shortly afterwards, in 1920, this time at the State Porcelain Factory, Karsavina was once again depicted in a porcelain composition that featured the ballerina as Giselle in Adam's ballet of the same name, designed by Dmitry Ivanov.

Anna Pavlova

A ballerina whose fame outlived the 20th century, Anna Pavlova's name remains forever etched in the history of world ballet. With her arresting appearance - her compelling dark eyes, the regular features of her pale oval face, hair smoothly and plainly drawn back, and her elegant, slender figure - combined with her fanatic, almost religiously ecstatic commitment to dance, Pavlova was regarded throughout the 20th century by ballerinas across the world as the model to emulate. The prominent Russian ballerina's first appearances in the Diaghilev productions brought her international acclaim, and very soon the magic of Pavlova's dancing won over the hearts not only of the European public but of ballet lovers all over the world.

Anna Pavlova as Lisa from the ballet "La Fille Mal Gardée". 1913

Photograph. Private collection, Moscow

Pavlova was careful about the way she looked not only onstage but outside the theatre, too: she was a well-groomed and level-headed woman who dressed elegantly and expensively - what we would call today a “style icon". The image of the refined, ethereal, polished prima ballerina of the Mariinsky Theatre had an impact not only on the art of ballet - it also inspired artists, photographers, directors and sculptors.

The flying arabesque in her “Dying Swan" solo from “Les Sylphides", choreographed in 1907 by Mikhail Fokine, was immortalized by the artist Valentin Serov for a “Ballets Russes" poster.

Fokine's “Les Sylphides" premiered in February 1907 at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg. Diaghilev introduced changes to the composition and design of the production for the French tour, adding new dances and commissioning new sets from Alexandre Benois. It premiered on June 2 1909 in the “Ballets Russes" season, the new version featuring Pavlova, Karsavina and Nijinsky in the lead roles.

Pavlova's collaboration with Diaghilev would not last - each was too forceful a personality. As Russian folklore characterizes such situations, “Two bears cannot live in one lair." Pavlova starred as Armide at the premiere of the Diaghilev company's “Le Pavillon d'Armide" in 1909, and danced Giselle in the 1911 “Ballets Russes" London tour, but by 1913 she had already established her own company, in which she would be, finally, the uncontested prima and absolute leader.

Pavlova's contribution to popularizing ballet in the 20th century was very significant. It would not be an overstatement to say that she introduced this art form to audiences around the world, touring with her company from 1913 to 1931, including appearances in various faraway locations, some of which seemed then absolutely out of touch with international cultural life. As a “missionary" of cultural enlightenment Pavlova visited India, South America, Africa and Australia: many people encountered classic ballet for the very first time at her performances, which were not just standard fare but the very best that ballet had ever offered. Pavlova took a lively interest in local dancing traditions, using elements of ethnic folk and ritual dances in her choreographic miniatures with exotic flair.

All her performances demonstrated the highest calibre of craft, irrespective of where she was appearing - whether in a theatre of international standing in one of the world's major cities or the assembly hall of a small town. Her passionate commitment to dance and her self-abandon on the stage were appreciated equally by sophisticated city aesthetes and by ordinary people from the provinces who were new to ballet. The young Frederick Ashton, who went on to found London's Royal Ballet, was first exposed to this art form when he saw Pavlova perform in Lima, Peru in 1917. Many years later he would often say that his choice of profession was determined by those moments, that Pavlova would become his inspiration for the rest of his life.

Pavlova's image can rightly be called one of the most popular and recognizable themes of ballet porcelain, the Thuringia figurines distinguished by elements of their distinctive local style, such as the requisite porcelain lace “flying" in a dance.

Sculptural composition of Anna Pavlova from the ballet "La Sylphide".

Porcelain Manufactory Aelteste Volkstedter Porzellanfabrik AG Germany, Thuringia, 1912-1945

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 30 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Pavlova was herself a dedicated amateur of porcelain art, keen on creating and modelling statuettes. Partnering with the sculptor Hugo Meisel, she created gypsum models of her self-portraits, which were used to produce corresponding porcelain statuettes at the Schwarzburger manufactory in Thuringia.

Pavlova took lessons in porcelain making at Meisel's workshop in Schwarzburger, and the sculptor later used these gypsum models to produce moulds for the elegant porcelain figurines. Werner Weiherer, director of the oldest porcelain manufactory in Volkstedt, highlighted this dimension of the great dancer's talent: “In 1927 the celebrated Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova visited Volkstedt and produced gypsum figurines representing herself. Hugo Meisel, the sculptor well known at the period, used these figures to create the porcelain statuettes."[3]

“Marvellous in its agility and grace, the porcelain statuette represents Anna Pavlova dancing ‘The Dragonfly' - a short ballet to Fritz Kreisler's piece ‘Beautiful Rosemary' - which she herself produced."[4] Both porcelain items are unpainted, drawing the viewer's attention to the great ballerina's movements in one of her most brilliant performances.

Similar porcelain compositions focused on Pavlova, created at the Volkstedt porcelain factory using gypsum models that she herself made, are in the collection of the Royal Ballet School, London.[5]

The “Ballets Russes” Company

The porcelain artists who created figurines at the Thuringia factories were also inspired by other Russian ballerinas from the “Ballets Russes", performers not as talented as Pavlova or Karsavina but whose dancing was nonetheless of a very high standard. It was Diaghilev's principle never to work with average performers. Ballerinas such as Vera Trefilova or Yekaterina Geltzer, even though they did not shine brightly, eclipsed as they were by world-class dancers, were never mere Cinderellas on stage. Their impeccable performances totally enraptured the public. But the Olympus of ballet is crowded, the ranks of seats for the great strictly limited - virtuosity is not always sufficient to qualify a dancer to join this pantheon. In case of a particular performer, many other circumstances, not directly related to ballet, may play a role. In Pavlova's case, it was the sheer versatility of her creative talents, as well as her impeccable taste in everything, including what might seem the least significant details. Or, as with Nijinsky, the complex, tangled intrigue of his remarkable, albeit brief, life both on and off stage proved important.

A soloist of the Mariinsky Theatre, Vera Trefilova performed with Diaghilev's company in 1921-1926. Although “Don Quixote" was never produced by the “Ballets Russes", the Thuringia porcelain artists somehow found postcards with photographs featuring one of Diaghilev's best dancers in one of her best performances, from her pre-Diaghilev period, and gave these images new life in porcelain.

Yekaterina Geltzer toured internationally with the Diaghilev company in 1910-1917, and was depicted by the Thuringia porcelain artists as a Bacchante. After the October Revolution in 1917, she cut all ties with her colleagues who had left Russia, becoming for a while the sole Soviet prima ballerina - there was no serious competition. She was the first ballerina to be awarded, as early as 1925, the title People's Artist of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

The Diaghilev company legacy

For two decades between their first Paris season and his death in 1927, Diaghilev managed to keep his company going, sometimes performing on different continents at the same time, an extremely difficult feat in itself. The First World War scattered its members across the world, while infighting and rivalry also took a toll. The “Ballets Russes" were in permanent financial difficulties.

The strategies that Diaghilev employed to handle such problems were astonishingly modern. A master of the game, with a good knowledge of the complexities inherent in the nature of celebrity and power, he was also skilful at marketing and adroit at working with the press.

Diaghilev's Russian ballet was not just a successful commercial project, but also an important cultural institution that would have a lasting international impact on the arts. The Diaghilev company's choreographic legacy remains an invaluable treasure trove of ideas that inspires dancers and choreographers across the globe to this day. The best works of Russian avant-garde artists became the basis for the stage design of the company's opera and ballet productions, and in large measure shaped the evolution of painting, the applied arts, design and fashion in the 20th century.

Porcelain artists caught this new artistic trend, applied it to chinaware, and thus represented these iconic figures in porcelain compositions and images. Artists from the Thuringia porcelain factories developed their distinctive, easily recognizable style of lacework porcelain whose elegance, grace, refinement and sense of air delight both aficionados of porcelain and ballet lovers equally.

- “Anthology of Russian Porcelain, 18th-early 20th century. Small-scale sculptures.” Collection of articles. T. 6. Book 1. / Compiler M. Korablyov - Moscow. 2015

- Khmelnitskaya, Yekaterina. “The ‘Ballets Russes’ in Porcelain. Anna Pavlova”. Gazette of the Vaganova Academy of Russian Ballet. 2016 (3)/

- “Tanzende Figuren aus den Sammlungen Alain Bernard und Vladimir Malakhov”. Berlin, 2009

- Dunaeva, Natalya. ‘Tamara Karsavina. “La rose de russie”’. “Actor-Legends of Petersburg”. St. Petersburg. 2004

- Agarkova, Galina; Petrova, Natalya. “The 250th anniversary of the Lomonosov Porcelain Factory in St. Petersburg. 1744-1994”. St. Petersburg, IPM - Desertina. 1994

- “Tanzende Figuren aus den Sammlungen Alain Bernard und Vladimir Malakhov”. Berlin. 2009

- Kudryavtseva, Tatiana. “Russian Imperial Porcelain”. St. Petersburg, Slavia. 2003

- “Ballet and Opera in Porcelain”. Broadcast by Rossiya-Kultura, aired on October 9, 2012

- Schwarzburger Werkstatten fur Porzellankunst, Wilhelm Siemen (Hrsg.), Wunsiedel 1993

- Dandre, Victor. “Anna Pavlova in Art and Life”. Moscow, Vita Nova. 2003

- Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research. Archives of the Dance: The Royal Ballet School Archives, A. Harman, 1991, Vol. 9, No. 1

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding Height - 23 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Watercolour on paper

Photograph

© Library of Congress, Music Division

Photograph. Private collection, Moscow

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 24 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 31 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Photograph. Private collection, St. Petersburg

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 29 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 26cm. Private collection, Moscow

Oil on canvas

© The Royal Ballet School, London

Photograph. Private collection, Moscow

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 27 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 19cm. Private collection, Moscow

Photograph. Private collection, St. Petersburg. 2019

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 19cm. Private collection, Moscow

Photograph. Private collection, St. Petersburg

Private collection, London

Photograph

© The New York Public Library

Hugo Meisel’s statuette based on the gesso model made by Anna Pavlova in 1927. Germany, Thuringia Aelteste Volkstedter Porzellanmanufaktur, 1927-1949

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Hugo Meisel’s statuette based on the gesso model made by Anna Pavlova in 1924. Germany, Thuringia Schwarzburger Werkstätten für Porzellankunst. 1927-1949

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photograph. Private collection, Moscow

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 30 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Porcelain, lace porcelain; modelling, polychrome overglaze painting, gilding. Height - 30 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Photograph. Private collection, Moscow

Sketch for theater poster

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London