"An Endless Dialogue" Ernst Neizvestny’s Illustrations to Fyodor Dostoevsky’s "Crime and Punishment"

Although Ernst Neizvestny is something of a symbol of our national independent art, it would seem appropriate to look back at some of the highlights of his biography. Born in 1925, Neizvestny was part of the generation destined for conscription and dispatch to the front line at the age of 18. War was undoubtedly a formative existential experience for him: joining the conflict as a private in the Airborne Division in 1943, he was very heavily wounded and even counted as dead. After the war, it took him several years to recover his health. Later, he studied - for about two years at the Academy of Fine Arts in Riga, and then at the Surikov Institute in Moscow. In 1955, Neizvestny joined the sculpture section of the Moscow branch of the Union of Artists of the USSR and, in 1957, participated in the Festival of Youth and Students. Even when Neizvestny was still a student, he was awarded prizes for his works, with state museums purchasing some of his pieces. He often took part in exhibitions and his career as a Soviet sculptor appeared to be off to a good start. However, when he was still a student, he began to have both artistic and ideological “differences with the system of Socialist Realism”. These differences were typical for students who were former soldiers: although many were Communist Party members, their extreme wartime experiences required special means of expression outside the mainstream of officially approved art.

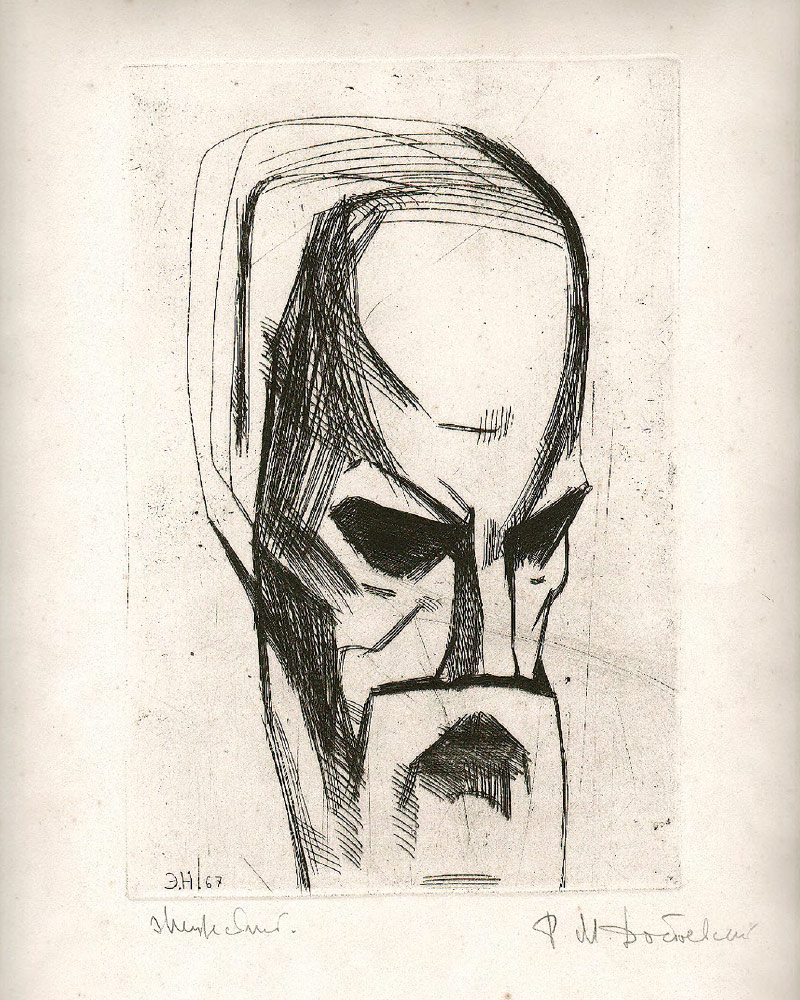

Ernst NEIZVESTNY. Fyodor Dostoevsky. 1967

Etching on paper. 29.5 × 20.0 cm (stamp); 47.5 × 34.5 cm (sheet)

Neizvestny was drawn to the subject of violent death: one of his first works in which he searched for new artistic idioms was the sculpture entitled “Dead Soldier” (1957). A year later, it was followed by “Man Who Took His Life” (1958). By the late 1950s and early 1960s, Neizvestny was already an accomplished artist with a distinct worldview and vast creative potential. He was already contemplating creating the colossal sculpture “Tree of Life”, which he expected to become a visual symbol of the unity of art and science - the unity of scientific and intuitive paths of learning about the world. The artist’s numerous creative ideas had a colossal existential drive. The ordeals that destiny had in store for him, however, were not at all of a creative nature. The most famous episode from

the artist’s life has been described many times: it was his bitter dispute with the then head of state, Nikita Khrushchev, in December 1962, at a show to mark the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Moscow branch of the Artists Union of the USSR (MOSKh). This conflict had quite drastic consequences: at the end of 1962, Neizvestny was excluded from the Artists Union and, accordingly, could no longer rely on assignments from the state. In 1962, Neizvestny set about creating “Orpheus”, his statuette of the Greek mythical hero: completed in 1964, it represented a muscled man on his knees, his arm bent at the elbow and pressed against his head, which is thrown back, and his other arm ripping his chest apart in order to touch the cords of his soul hidden under his skin.[1] This sculpture conveyed the theme of human suffering and despair with extraordinary forcefulness.

Neizvestny was genuinely interested in philosophy. At this point, it would be appropriate to note that, while training at art school, he also attended lectures at Moscow State University’s department of philosophy. At the lectures, he became acquainted with Yuri Karyakin.[2] Later, echoing Pushkin’s designation for the enduring friendship formed in youth, Neizvestny would call Karyakin “a lyceum friend”, and the writer and the artist remained close for many years. Even during his student days, Karyakin developed a scholarly interest in Dostoevsky, and this interest determined his further professional career. Karyakin wrote an article “Anti-Communism, Dostoevsky and ‘Dostoevshchina’” (1963), the publication of which in the Prague-based magazine “Problems of Peace and Socialism” marked the beginning of the writer’s reinstatement in Russian public cultural discourse. Later, Karyakin continued his meticulous study of Dostoevsky’s journals, drafts, notebooks, and social commentary.[3] Neizvestny undoubtedly shared his friend’s keen interest in Dostoevsky, although what produced a truly powerful impact on him was Mikhail Bakhtin’s book “Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics”.[4]

A philosopher, a literary scholar, a solitary genius, Bakhtin spent more than 30 years isolated from his professional community because of the state’s repressive policies. Nonetheless, the tract published in 1963 was in synch with one of the main worldwide trends of 20th-century philosophy: engagement with the problem of the Other. This problem was revealed in his analysis of Dostoevsky’s creative method as introducing the concept of dialogic narration, and through this analysis of Dostoevsky’s texts, he produced his definition of the “new type” of novel: unlike the monological novel, in which the author’s position is unequivocally revealed, this new type of novel is polyphonic.

Later, Neizvestny wrote: “The idea of polyphony ... this issue was elaborated on by Bakhtin brilliantly.”[5] Polyphony, dialogism, antinomy - all these categories drawn from Bakhtin’s work resonated with the artist as he pursued his own creative goals. The idea that he found particularly engaging was “a plurality of independent and unmerged voices and consciousnesses”[6]. Bakhtin’s discoveries contributed to expanding the artist’s conceptual territory. Today, one can quite confidently suppose that Bakhtin supplied Neizvestny with a theoretical foundation for his creative quest while also enabling him to follow “in the philosopher’s steps,” to undertake his own enquiry into Dostoevsky’s prose, but using the method that he was a master of: graphic art. As a result, he created hundreds of drawings based on Dostoevsky’s works.

These numerous graphic pieces were not straightforward illustrations to the texts. Later, Neizvestny explained his goals in a fairly detailed manner in his text “How I Illustrated Dostoevsky”[7]. Even his use of terms indicates Bakhtin’s influence: “I appreciate in Dostoevsky his polyphony,” wrote Neizvestny, “his multitude of voices and the conflict of his own inner contradictions.”[8] In his analytical work, Neizvestny appears to be following in Bakhtin’s footsteps; the artist, however, is not a literary scholar or a critic. Comparing Bakhtin’s monograph and his creative method, Neizvestny emphasised that, “my advantage [consisted in that] I studied Dostoevsky, only not through analysis but using a method of parallel creativity.”[9]

Neizvestny did not so much seek visual parallels for the writer’s prose, but rather had a more global intent: visualising the philosophical substance of a literary work. And not just of any particular novel, but of the philosophy of Dostoevsky’s writings.

One of the crucial points for Neizvestny was to approach Dostoevsky as an artist of the tide: “for me ... [Dostoevsky was] an artist of the tide. That is, he moved along with life, not creating individual masterpieces, but as if creating objectified meditations of his mental states, his ideas, projected as an end-to-end movement through an entire life, from the first jolt to infinity. And in this movement, he tackled several grandiose themes which run through his novels as guiding ideas. The novels, sure enough, are constructed in keeping with the rules of literature - with an introduction, an elaborate plot, something in the way of denouement, and an intrigue. This is purely literary workmanship. But philosophically, Dostoevsky has a prodigious amount of ideas, and I singled out the ones that spoke the most to me.”[10]

So, what are these “philosophical ideas” singled out by Neizvestny? First, this is the idea of dialogue - the inner dialogue, the clash of different voices within an individual. And, as a consequence, this becomes “the polyphony of human consciousness”. Following in Dostoevsky’s footsteps and reaching deep into his heroes’ minds, Neizvestny created his own original metaphors, and deve I oped his own visual symbolism. Gradually, these ideas translated into 12 etched compositions that Neizvestny included in a portfolio published in Italy in 1967.[11] One can say that these compositions were the crystallisation of a multitude of previous artistic explorations.

Little by little, scores of drafts produced this series of etchings. The artist displayed these pieces at several shows, including a print exhibition in Moscow and his solo show in Tallinn. It was important for Neizvestny to show this portfolio to Bakhtin: he found an opportunity to pass the folder with the etchings to the philosopher, who was then living in a retirement home in Grivno. Later, in an interview to a Polish reporter, Bakhtin described his impressions of the Neizvestny prints: “It was the first time that I sensed a true Dostoevsky. Ernst Neizvestny managed to capture the universal nature of the writer’s image ... This is not illustration, this is an emanation of the writer’s spirit ... [He] managed to convey the unfinished state of human beings in general . This is a continuation of Dostoevsky’s world and imagery in a different medium - in the medium of graphic art.”[12] Attitudes to Dostoevsky in the Soviet Union, meanwhile, were undergoing a cardinal change. Within 10 years in the 1960s, this semi-prohibited author was reinstated as a Russian classic, and his novel “Crime and Punishment” was reintroduced into the school curriculum. Articles and books about his life and work started to be published, and academics began to deliver public lectures about the writer; Russian Dostoevsky scholarship started to flourish.

When, in the late 1960s, the Nauka publishing house set about preparing an academic (fully annotated) edition of “Crime and Punishment”, it was proposed that Neizvestny’s images be used as illustrations. The idea of using Neizvestny’s illustrations was proposed by the publishing house’s deputy director Anatoly Kulkin,[13] a coursemate of Karyakin at the university and a friend of the artist. Besides, Neizvestny already had some experience illustrating literary works - he had created drawings for masterpieces by Dante[14] and Plato. But the Dostoevsky project was a special one: this time, he was motivated by the interest of a researcher.

In the late 1960s, however, the partial liberalisation of cultural life that had taken place during the Thaw came to an end. In those years, censors could withdraw their approval even in relation to works and projects that had been previously allowed. This was what happened to Neizvestny and his participation in the publication of an academic volume was now considered undesirable. In his article “Neizvestny, Dante and Dostoevsky”,[15] Kulkin describes in great detail the ferocious pre-publication tug-of- war between editors and scholars on the one hand and censors on the other. However, despite all these spokes in the wheel, the book with Neizvestny’s illustrations was released.

The book contains 18 illustrations - six more than in the Italian portfolio; some of them develop the earlier themes and some tackle new ones. Perhaps Neizvestny came to think that greater loyalty to the text of “Crime and Punishment” was essential. The artist gave each composition a name. Thanks to “How I Illustrated Dostoevsky”[16], Neizvestny’s account of his work, one can familiarise oneself with the artist’s comments on the illustrations. It should also be mentioned that in these illustrations the artist’s visual idiom becomes more diverse: they include airy outlines and a line drawing of Raskolnikov’s profile, as well as a practically Naturalist representation of the laughing old woman’s face, and the energetic, highly contrasting imagery of the drawing featuring the “cracked mirror”.

One of the new illustrations is a portrait of Dostoevsky. Neizvestny himself said that among all known images of Dostoevsky, the one he liked most was Vasily Perov’s “very honest Realist portrait”. Placed at the beginning of the tome, Neizvestny’s own portrait of the writer, however, is a far cry from Naturalist style. That artist himself called this image “the ultimate abstract portrait”. The portrait features over-emphasised forms: the forehead protrudes mightily, black shadows conceal the eyes, and the skull’s structure is accentuated. However, this stylised image resembles the real person: Dostoevsky is recognisable. In his commentary, Neizvestny remarked that, in this somewhat abstract piece, he attempted to create an expressive emblem, ignoring details.[17]

The writer’s hands evoke intense psychological strain. It is curious to see how the artist uses this visual metaphor: in one composition, the hand is pressed firmly against the head; in another, the hand semi-covers the eyes; in the third image, the clenched hand holds several human faces. This symbol also becomes becomes “polyphonic”: in one instance, a symbol of inescapable fate, at other times, a symbol of protection and safeguarding.

The bony hand catching hold of a toddler’s head becomes a symbol of death. In Neizvestny’s graphic pieces, the hand is a very important visual element existing seemingly independently from the human body. This shows the artist’s special attitude to corporality: he not only deforms and over-emphasises, but also works with the human body as if it is “an open form.”[18] The physiology of the body is something completely foreign to Neizvestny: his corporality is very close to literary imagery.

This can be seen especially clearly in his special treatment of the human personality. Elaborating the idea of the polyphony of human consciousness, Neizvestny comes to the following conclusion: “there are three ideas of a human appearance ... There is the human face, which bears the impress of both nobleness and ignobleness. This face is changeable. There is the visage, which is the divine substance shining through the human face; it is luciferous and metaphysical. And there is the guise. The guise is a mask. It is satanic.”[19] This notion that a human personality can have three different variants - “a face, a visage, and a guise” - empowers the artist to emphasise Rodion Raskolnikov’s transformations. One of the first illustrations features the young man’s profile, a barely traced outline on a white sheet: stubble on the chin, a skein of tangled hair over the forehead, the eyes half-closed, he is completely self-absorbed. This is Rodion’s human face. In the next illustration, we see a face that appears to consist of two parts - the young man’s face morphs into an ugly mask: “This is Raskolnikov’s guise, a split Raskolnikov. What is this? A split face does not necessarily spell out an end. Raskolnikov is divided. But this is already close to a guise, this is like a split mirror,”[20] wrote the artist about this illustration. In his commentary on another illustration, called “Arithmetic”, Neizvestny writes: “What is arithmetic in this novel? ... Raskolnikov dreams. Although his dreams can be considered as somewhat false. [He dreams] that having killed the old woman he will be able to provide for himself as a talented person - not a louse but a genius - and thus bring happiness, through himself, to humankind and even to people close to him. In his estimate, by killing an old woman who nobody needs or cares about and making many people happy, he takes a positively reasonable and beneficial step. This is what arithmetic is about. This is what drives revolutions, killings, and great bloody reformers. Everyone starts with an estimate. But Dostoevsky in this novel (and his novel is like a laboratory flask, like a laboratory where an experimental form, perceivable by reason, of such acts is carried out) learns the implications of this bivalent logic ... It is as if he established a diagnosis for present-day terrorism too.”[21]

As for the idea of dialogue itself, in Neizvestny’s art, it translates into the imagery of arguing “doubles”. This composition features what looks like a clash of two male profiles facing each other, nearly identical except that one man holds an axe and the other a cross. Between these two profiles, there is a smaller man’s head - and we understand that this argument is taking place inside this small-sized human head. The disputants are far bigger than the little man himself. In fact, this is a dispute between the axe and the cross, violence and faith, murder and life.

“An infinite dialogue” is how Neizvestny characterized the novel “Crime and Punishment”: “Dostoevsky’s antinomy is like an endless game of Yes or No. His novel is an endless dialogue: God exists - God doesn’t exist, killing is OK - killing is not OK ... Dostoevsky does not give an answer.”[22] And doubles arguing with each other are the visual metaphor of this dialogue: the dialogue of “narrow-minded positivism”[23] and the mind of a believer, with no end in sight. In one of his interviews Neizvestny would say: “Dostoevsky’s strength is in his ruthlessness”[24]. So, does the artist suggest that this inner dialogue turns out to be ruthless and endless?

Arguably, this is not so. Neizvestny’s illustrations to Dostoevsky’s novel not only reflected the hopes of our nation’s artists of the 1960s, but also continued the Humanist tradition originating in the Renaissance era. Virtuosity in drawing, bold composition and visual expressiveness impress on the viewer the artist’s profound conviction that evil and powerful forces that seem to have such a potent grip over human consciousness can be contained. Neizvestny believes that the human spirit can get the better of “the split of [a person’s] own consciousness” and stay on the side of goodness. And, paradoxically, through the endlessness of this ruthless dialogue there appears an image glorifying the human being’s holistic nature.

- Since 1994, a smaller-sized replica of this statue has been used as the prize for the annual Russian TEFI national broadcasting award.

- Yuri Fyodorovich Karyakin (19302011) was a philosopher, writer, literary scholar and public figure.

- Yuri Karyakin’s books Re-reading Dostoevsky (Perechityvaya Dos- toyevskogo) (1971), Raskolnikov's Self-Deception (Samoobman Raskolnikova) (1976), Dostoevsky on the Eve of the 21st Century (Dostoyevsky i kanun XXI veka) (1989), and Dostoevsky and the Apocalypse (Dostoyevsky i Apokalipsis) (2009) are valuable contributions to Russian Dostoevsky scholarship.

- Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics (Problemy poetiki Dostoyevskogo) (Moscow: Sovetskiy Pisatel, 1963).

- Ernst Neizvestny’s interview “How I Illustrated Dostoevsky” (Kak ya illyustriroval Dostoevskogo) (from A.M.Kulkin’s archive). Last accessed on Aug. 19, 2021. (Hereinafter referred to as “the Neizvestny interview”.)

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Thanks to Karyakin’s ministrations, the portfolio (series) of 12 compositions was published by the Italian publishing house Giulio Einaudi Editore.

- Quoted from: Per Dalgaard, “Neizvestny’s Dostoevsky Illustrations: Bakhtinian Polyphony Applied to Visual Art,” Russian Language Journal 136-137 (1986): 133-146. Last accessed on Aug.19, 2021.

- Anatoly Mikhailovich Kulkin (19282014) was a philosopher, a staffer at the Novy mir magazine, an editor at the Nauka publishing house. He was Yuri Karyakin’s fellow student at Moscow State University’s department of philosophy and a friend of Ernst Neizvestny.

- Dante Alighieri, Minor Works, Literaturnye Pamyatniki [Literary Monuments] series (Moscow: 1968).

- Anatoly Kulkin, “Neizvestny, Dante and Dostoevsky,” Chelovek, no. 6 (2016): 145-161. For an expanded version of Kulkin’s memoir. Last accessed on June 24, 2021.

- The Neizvestny interview.

- This image was featured on badges produced for a session of UNESCO in 2006, which was declared the Year of Dostoevsky by UNESCO.

- “Pure form” is the term used by John Berger in his description of Ernst Neizvestny’s artistic method (John Berger, Art and Revolution. Ernst Neizvestny and the Role of the Artist in the U.S.S.R. [Iskusstvo i revolyutsiya. Ernst Neizvestny i rol' khudozhnika v SSSR] (Moscow: 2018), 64-78.)

- The Neizvestny interview.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ernst Neizvestny, The Centaur: Ernst Neizvestny on Art, Literature, Philosophy (Kentavr: Ernst Neizvestny ob iskusstve, literature, filosofii) (Moscow: 1992), 111.

- Ibid.

- The Neizvestny interview.

Etching on paper. 20.0 × 14.5 cm (stamp); 43.0 × 30.5 cm (sheet)

Etching on paper. 29.3 × 20.5 cm (stamp); 46.7 × 34.3 cm (sheet)

Etching on paper. 27.0 × 20.3 cm (stamp); 46.8 х 34.3 cm (sheet)

Etching on paper. 29.0 × 20.5 cm (stamp); 46.0 × 34.0 cm (sheet)

Etching on paper. 29.7 × 20.8 cm (stamp); 43.7 × 31.4 cm (sheet)

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts

Etching on paper. 29.5 × 20.2 cm (stamp); 47.5 × 34.7 cm (sheet)

Etching on paper. 27.4 × 19.1 (stamp); 34.5 × 45.5 (sheet)

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts

Etching on paper. 29.7 × 20.8 cm (stamp); 43.7 × 31.4 cm (sheet)

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts

Etching on paper. 29.5 × 20.5 cm (stamp); 46.0 × 34.5 cm (sheet)

Etching on paper. 29.8 × 24.0 cm (stamp); 45.2 × 34.3 cm (sheet)

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts