Russian Pop-art

"A country with a total shortage of goods and endless queues can't have pop-art,” the Soviet avant-gardist Vitaly Komar had said before he invented, in 1972, a politicized version of postmodernism wittily called "soc-art” (also known as "sots-art). Some of the prominent "socartist's” friends and colleagues did not believe his statement and made joint efforts to develop the artistic forms that the poet Genrikh Sapgir called "Russian pop-art”. Today, 35 years later, the question of Russian and Soviet pop-art remains open - did Russia have a pop-art style or not?

Before any attempt is made to answer this question, the undeniable fact that Russia does have pop-art today should be emphasized. It has been widely elaborated in the work of several prominent Russian artists who have younger colleagues following in their footsteps - as well as in that of art designers, architects, decorators and fashion designers and all those who adopt and adapt their creative ideas for use in commercial and practical art forms. Pop-art is supported by an increasing number of collectors and anyone interested in new aesthetic forms. This is why it can be maintained that pop-art does not simply exist - it is fashionable today.

-

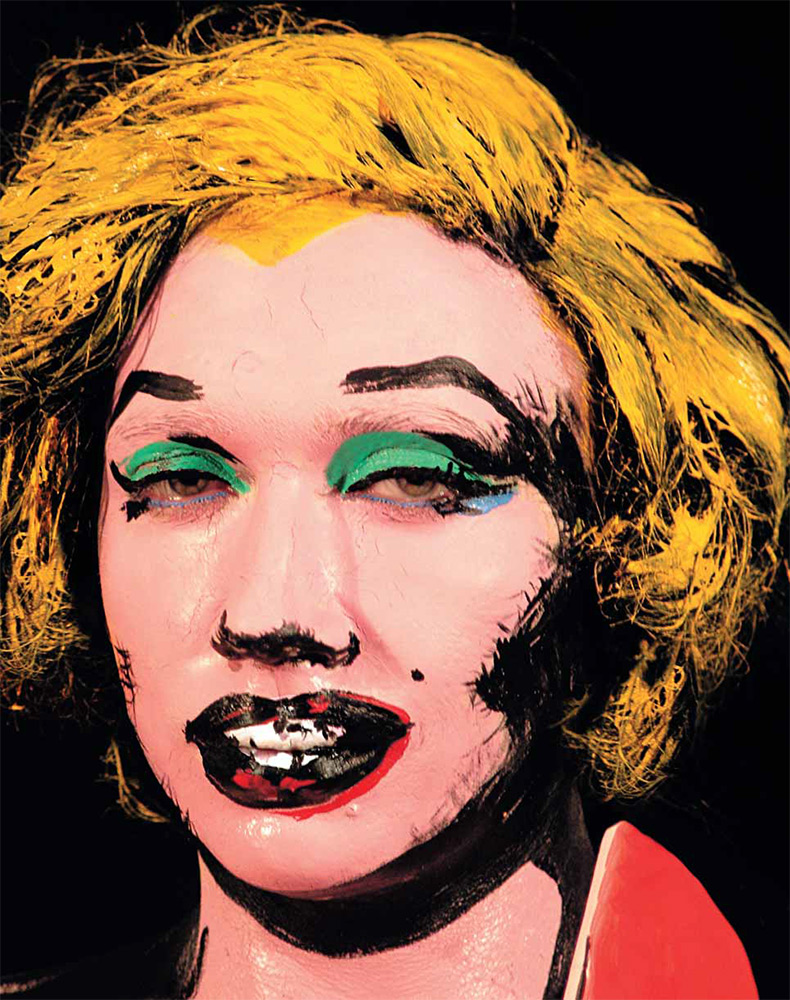

Vladislav MAMYSHEV (MONRO). Monro-Warhol-Monro. 2005

Colour print on canvas, Society of Modern Art Collectors

Over the decades after the formation of the style, its ideology became more clear and precise. First and foremost, pop-art always prefers mass phenomena to the unique - that is its principal, generic feature. It aspires to the "public" and the universal. The term designating the style - "pop", a short form of "popular", that is "belonging to the people" - attests to such priorities. Pop-art is oriented towards "the people's choice", the mass taste shared by the population (in all domains, art itself excepted), and objects and images replicated in numerous copies. Pop-artists are fond of the most marketable and popular articles. They place them in museums, turn them into monuments.

On the other hand, pop-art hates exclusiveness, it hates single, unique pieces, exclusive or expensive rarities, for the style is against any sense of traditional caste, whether elitist or Bohemian. Pop-art disregards subcultural milieus and local traditions; the peculiarities of the "spirit" or "genius" of a particular historical locus have no appeal. It is not predisposed in favour of any class, age or confession and their corresponding groups of the population. Like any other global style, pop-art perceives itself as the art of the global, universal problems of modern civilization.

Pop-art is indifferent to power and neglects the formula of culture as an opposition between an official camp and non-conformism. According to this mental stereotype, art is born in a conflict between the fighters of an intellectual underground with the mastodons of the official "fine arts". The wider population does not take part in such a tournament, remaining content with the role of passive spectator. But when the encounter becomes drawn out to a great length, and the fighters tire, the bored spectators leave the stands and go to enjoy themselves in Disneyland or the Exhibition of the Achievements of People's Economy (VDNKh). Pop-art departs with them too.

Another important preference of pop-art is its love for every kind of culture considered "low", "street", or trivial and worthless, including the sphere of what Mikhail Bakhtin called "the material bodily lower stratum". Pop-art works with the phenomena rejected by good taste as "inferior" things, "unliterary" speech and "anti-aesthetic" images. It strives towards everything that is unstandardized, not approved, not assimilated by "higher" culture: newspaper images, advertising videos, taglines, labels, pictograms, guide signs and countless other images from the modern urban context. To pop-artists, all these incoherent objects are valuable for one common quality: they are vehicles of comprehensible and commonly accepted sign systems which allow the artist to communicate with almost every member of society. Just as Fedor Dostoevsky who, in his time, made a literary norm of the cheap novel, or Mikhail Larionov who presented the signboard as a model for modern painting, pop-art establishes the principles of new art in conformity with the law of mass communication idioms. At the same time, all the language forms and figures of speech which are exalted above the horizon of everyday life and referred to as embodying elegance and discriminating taste, are demonstratively rejected by pop-art, irregardless of who is exploiting them - whether the president of an Academy, or an "underground" modernist.

The third characteristic feature of popart is that it deals only with the reality of a world of common, everyday things and images. When the pop-artist paints a portrait or a landscape, what he paints is not "la nature vivante", but rather an already existing image - an advertisement, a newspaper photograph, a television image, a theatre playbill or a poster. Pop-art likes changing the scale, framing, simplifying, and "animating" the image. Nevertheless the pop-artist always remembers that the image he wants to copy is just a picture (or a set of dots on the screen), and always emphasizes the definition, pixels, lines and stains of printer's ink. Pop-art imitates figurative languages, but its self-perception is also that of a language - rather than of an authorial, individual speech and utterance. In the work of pop-art the author's voice should not be heard, and (ideally) his personality, soul and character cannot be revealed. This does not mean that pop-art is empty, cold and inhuman. Just the opposite, it can use banal, popular signs to build different images, varying in terms of their meaning and emotional charge, and relating stones of love, death, loneliness and glory. It is no surprise that pop-art is eager for liminal states of consciousness: it was born and "grew up" together with existentialism, as well as structuralism and semiotics.

Could pop-art appear in a Sov'et society in which there were no supermarkets, no publicity, nor any developed sphere of illustrated journals, comics and the like? The scarcity of everyday life of the Sov'et years was indeed not rich in such diverse v'sual information, but it was nevertheless available, as were "inferior" languages and semiotically rich everyday objects with the potential for metaphorization.

Railroad posters painted on tin plates, fire-drill stands, direction signs, sweet wrappers, packets of cigarettes with their mountain scenes - in the late 1960s and early 1970s all these samples of miserable typographic design suddenly invaded the "assemblage" pictures of Russian avant-garde artists. It is difficult to explain this twist toward object and sign through any direct influence of American art.

Apparently, in the mid-1960s Russian art experienced the same kind of crisis as the American avant-garde of the late 1950s, as art's necessity to structure and re-shape aesthetically the actual context of contemporary life was lost. Art became the practice of fixation of the artist's neuroses and personal phantasms. Such was the situation of abstract expressionism in the USA, with its refusal to find any connection between the artist's emotional experience and the outer world of "profit" and Hollywood-style mass culture. In the USSR, the same kind of autism and escapism, with the artist's flight to cultures of the past or atemporal metaphysical meditations, flowered in the work of non-conformist figures and was even reflected in the dream-like deserted landscapes of painters who represented the liberal wing in the Artists' Union.

Despite the difference between the USSR and the USA their cultural situations were similar - the artists rejected modern society even more than that society rejected them. They literally hated the aesthetic aspects of the environment, despising and feeling ashamed of them, and therefore constructed their art on the principle of radical opposition. It should be pointed out that the feeling was not (or not only) one of political aversion to the regime, but rather aesthetic disgust at the conditions of life and forms of communication with their fellow countrymen. As a result, the avant-garde began to deteriorate, eventually degrading into a "drawing-room" mannerism characterised by self-contained narcissism. Only a few brave figures revolted against this degradation of art.

The circle of rebels in New York who turned against the "respectability" of abstract expressionism consisted of five members - Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselman, James Rosenquist and Claes Oldenburg; later their circle would widen, but not to any considerable extent. Very few artists in Paris and Rome decided to adopt the ideological principles of pop-art and break away from their existing "lofty" style. It is thus not surprising that the circle of revolutionaries and opponents of "metaphysical" art in Moscow in the mid-1960s was also narrow - defined principally by Mikhail Roginsky, Mikhail Chernyshov and Boris Turetsky. With the arrival of a younger generation of artists in the 1970s the movement of local pop-art expanded, amounting to ten painters and sculptors - now including also Alexander Kosolapov, Leonid Sokov, Igor Shelkovsky, Rostislav Lebedev, Dmitry Prigov, Ivan Chuykov, and Alexander Yulikov - organized in several cooperative groups. As is usual in pop-art, each of the artists found his variant of sign and object, his own recognizable brand, and developed it for several years, multiplying it in numerous works.

How did it happen then that only ten or 15 years later, when the first critical and historical publications on the new, "post-metaphysical" stage of the Soviet avant-garde began to appear, that the term "Russian popart" fell into disuse, being substituted by "soc- art" and "Moscow conceptualism"? For many originators of Russian pop-art, as well as their colleagues and followers, the pop-art experiments of the early 1970s were a launching platform from which they catapulted themselves into later artistic movements. Evolutionary progress through different stylistic streams is typical for Russian art in general: almost each generation of Russian artists has had to assimilate the voluminous and various experience of Western art, trying at the same time to elaborate national versions of the styles concerned. This situation resembles an intensive course one which concludes with a transfer to yet another institution of intense training, instead of to a professional job.

Moreover, many artists who started working in the pop-art manner emigrated to the West as early as the mid-1970s, where they chiefly exploited the recognizably Soviet "soc-art" style. Finally, Russian pop-art was not supported by exhibitions and criticism; it was not properly announced and positioned alongside allied movements, and nor was it supported by purchases and orders. As a result, the pop-art experiments of the 1970s were completely forgotten until the end of the 1980s. The few people who remembered and preserved those works considered Russian pop-art an episode without any continuation, little more than a curious incident.

By then capitalism had returned to Russia and, in the blink of an eye, built a consumer society and an industry of mass-market entertainment; the process demanded that modern artists acquaint themselves with the international experience of neo-pop-art. In such a situation, the artistic experiments of more than 30 years ago suddenly became part of a tradition which received a continuation, and a vital support for today's creative work.

Sponsors of the Project:

"Stroiteks" Co., General Power & Fuel Co., the Embassy of the USA in Moscow

The Exhibition was organized by:

The Tretyakov Gallery Valentin Rodionov,

Director of the Tretyakov Gallery with the participation of the "Drugoe Iskusstvo" ("Other Art") Museum (L.Talochkin Collection) in the RGGU (Russian State Humanitarian University), the "Ekaterina" Cultural Foundation, and the "Novyi" ("New") Foundation

Installation. Porolon. 500 by 300 by 150 cm. Ridzhina Gallery

Wood. 97,5 by 52,5 by 31cm. State Tretyakov Gallery

Wood, oil, handle. 160 by 70 by 10 cm. “Drugoye Iskusstvo” (“Other Art”) Museum

Acrylic on cardboard, Property of the artist

Wood, plaster, oil

(Part of the installation “Scarce Goods ” for a canteen at DINAMO factory. Author’s copy 2005). “Novy” (“New”) Foundation

Oil on canvas. Property of the artist

From a series “Museum Paintings”. Oil on canvas. Society of Modern Art Collectors.

Hardboard, gouache, canvas, plaster. 100 by100 by 50cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Hardboard, enamel, Property of the artist

Oil on canvas. 140 by 168 cm. Marat Gelman Gallery

Hardboard, oil, mixed media. 153,5 by 99 cm. The Ekaterina & Vladimir Semenikhin collection

Installation, detail. Oil on canvas. 200 by 150 cm. Property of the artist

Installation. Glass, metalworks, flowers. 400 by 250 by 600 cm. Property of the artist