A Funerary Memorial for Arkhip Kuindzhi

Commissioned by the “Kuindzhi Society of Artists”, Alexei Shchusev worked on the monument to his mentor over the course of two years, modifying his vision together with his collaborators, notably the artist Nicholas Roerich. Such a process, involving a synthesis of the arts, would prove significant in Shchusev’s later work, including the Lenin Mausoleum.

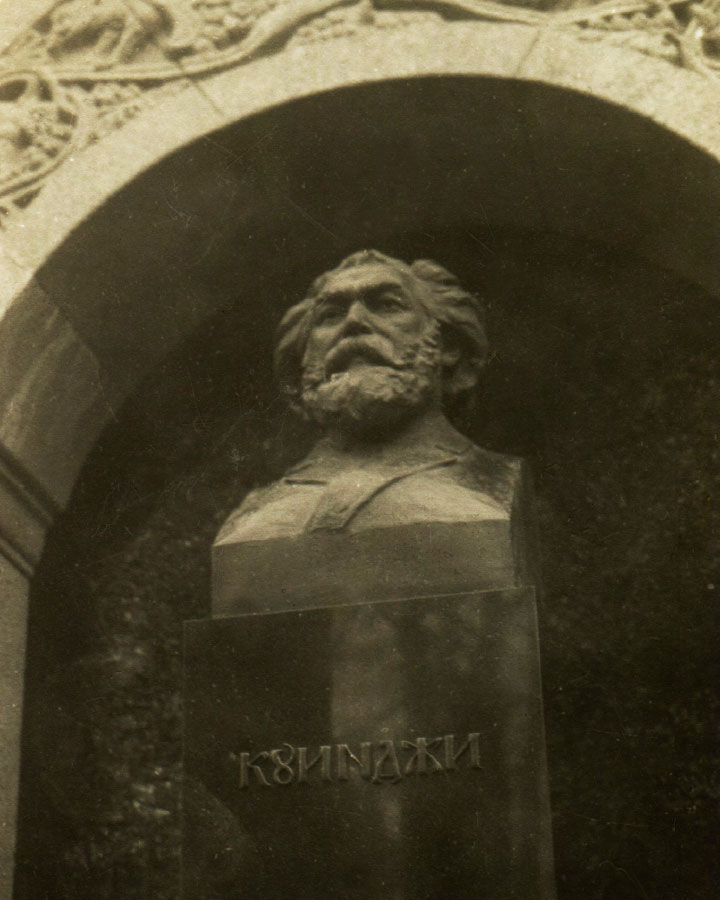

Kuindzhiʼs memorial at the Smolensky Cemetery in St. Petersburg. Detail. November 1914

Photograph by Alexei Shchusev. Private collection. First publication

The great Russian painter Arkhip Kuindzhi died on July 11 1910, and was buried in St. Petersburg's Smolensky Cemetery. Two years before his death, with a group of his apprentices, Kuindzhi had established the “Society of Artists" that bore his name: its founding members included Vladimir Beklemishev, Albert Benois, Richard Berggolts, Fyodor Bernshtam, Konstanty Wroblewski, Alexandre von Hohen, Vladimir Makovsky, Valerian Loboikov, Nicholas Roerich, Arkady Rylov and others, as well as the architect Alexei Shchusev (already then a member of the Academy of Fine Arts). Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, president of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, was an honorary member of the Society, while Emperor Nicholas II became its patron.

In April 1911, the Society suffered a new loss when its first chairman, Konstantin Kryzhitsky, took his own life. He was laid to rest next to Kuindzhi, and Kryzhitsky's friend, the sculptor Maria Dillon undertook to produce his tombstone. This development put the question of a memorial to Kuindzhi himself high on the agenda, and the Society turned to Shchusev:

“Dear Alexei Viktorovich. The Kuindzhi Society is contemplating the production of a memorial to Arkhip Ivanovich. Nicholas Roerich has told us that you are willing to design it... The Committee... hereby informs you that it hopes very much that you will carry through with your proposal."[1]

While studying at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in 1891-1897, Shchusev would visit Kuindzhi's studio, as well as attend the artistic gatherings that the artist organized for his apprentices. In 1901, Kuindzhi and Repin supported Shchusev's candidacy for a professorship at the Academy, but the young architect did not then receive the necessary votes and took a job as a part-time architect with the Synod. Thus Shchusev's offer to design Kuindzhi's tombstone, without requesting a fee, was tantamount to creating a tribute to his teacher.

Shchusev's initial sketches, showing how his concept evolved, survive. He was experimenting in a neo-classicist vein, envisioning the memorial either as a stepped pedestal crowned with a funeral urn, or as an obelisk, or as a sarcophagus. Shchusev presented his design to the Society in the spring of 1912, in the form of a gravestone of low height running the entire width of the plot, with a low fence around its perimeter. The slab's midsection, with the artist's sculpted profile portrait, would be highlighted by a circular pediment and supported with bolsters on each side. However, this version of design was not approved, as “Apollo" magazine briefly reported: “Recently the Society named after the deceased [Kuindzhi] rejected the design of his gravestone produced by Shchusev since, in its view, it was too modest."[2]

In June 1912, the Society announced a competition for the Kuindzhi memorial: “Any form of sculptural or architectural design is acceptable... the size of the site is 4 by 3.5 arshins [2.8 by 2.5 meters]. [submission] deadline: November 1."[3] Eighteen entries were submitted in all, and the first prize was awarded to a student of the Arts College, Valerian Voloshin; the second prize went to the sculptor Mary Dillon,[4] the third to the artist Andrei Nikulin. Beklemishev participated too, presenting a neo-classical design with Kuindzhi's bust mounted on a high pedestal with the figure of a youthful female muse mourning at its base.[5] However, a general meeting of the Society failed to approve any of the entries, possibly because none fully reflected the spirit and personality of the prominent landscape artist.

Carefully studying these entries, Shchusev set about producing a new version of the memorial, one that would retain the best features of his earlier work. This time, however, Shchusev would make use of a Russian style.

Like the previous version, in the new design the headstone ran the entire width of the plot, only it was much higher, more resembling a wall that partitioned the monument off from the rest of the cemetery. In the middle was a semi-circular vaulted niche with Kuindzhi's bust on an elegant prism-shaped pedestal, against the background of a coloured mosaic.

In subsequent sketches the architect projected the midsection with the niche, topping it with a pediment. On the lateral wings of the protruding section he placed small icons: one of St. Archippus above the date of the painter's birth, another, of the Saviour, over that of his death. These images were echoed with a small cross against a golden background in the centre of the pediment.

Whereas the initial version had featured an abstract (or, rather, landscape-like) design for the mosaic in the niche, in the second the imagery became more specific, featuring intertwining vines (the biblical symbol of Christ, resurrection, paradise). Cornices and eaves mouldings were decorated with floral patterns in relief. The platform in front of the gravestone was elevated several steps above ground, with a low border on its sides serving as a bench. Shchusev accomplished thus version in less than a month and submitted it for approval to the Society's demanding jurors. On December 9 1912, “Zodchy" (Architect) magazine apprised its readers: “Having reviewed the sketches and models submitted for the Kuindzhi memorial competition, the general assembly of the members of the Society named after the late professor. selected the out-of-competition proposal presented by Alexei Shchusev."[6]

Almost immediately after securing the commission, the architect started negotiating with the painters whom he wanted to enlist for the project: they would be artists who had known Kuindzhi well. Shchusev asked Nicholas Roerich, with whom he worked most productively on a number of projects at this time, to design the mosaic panel. Roerich perhaps accomplished the first version of the outline drawing at the end of 1912, but it has not survived. To judge by the correspondence between the artists, it did not quite satisfy the architect:

“Dear Nikolai Konstantinovich!

Please forgive me for having kept your sketch for so long. I've been having a difficult time and now I'm sending the sketch to you, asking you to look at the tracing paper. My idea now is to picture the Byzantine tree in a Byzantine fashion, namely patches of green on black, with bough and leafs inside. The leaves could be golden; there could be a weeping birch tree. Try it yourself. Such a background will look calmer and less pretentious, and with your colours and skills it will come out excellently."[7]

Eager to establish what he considered the right direction for the artist's experimentation, Shchusev drew his vision of the composition and themes for the mosaic panel on the tracing paper. Accomplished in muted colours, this sketch has survived: it features a tree, stylized in its ornamentation, with large flowers as finials of spiral-like branches. Such stylization can be found in Byzantine art, as well as in Old Russian carved woodwork and liturgical garments, but Shchusev fitted this motif into the pre-set architectural forms masterfully, adapting it for such material as smalt. The architect's notebooks show that at the same time he was contemplating a similarly abstract image of a birch tree for the mosaic.

For the portrait statue of Kuindzhi, Shchusev wanted to use a bronze cast of a gypsum bust of the artist that Beklemishev had created in 1898 and replicated in marble in 1912.[8] He suggested that the stonework for the monument itself should be executed in Pavel Chirkov's workshop.[9] Commissioned to produce the mosaic following the approval of Roerich's design, the mosaicist Vladimir Frolov was also put in charge of record-keeping for the project by the Society.[10] In March 1913 he wrote to Shchusev:

“Dear Alexei Viktorovich!

In response to a request of the Kuindzhi Society’s board, I humbly ask you to engage with Arkhip Ivanovich’s memorial - time is passing, and progress is needed in this matter. In private conversations I have made tentative enquiries as to the funds needed for the production of the model and its details, and I think there will be no objections on this score. Especially since the board’s old membership is gone, and the new board includes nearly all of Arkhip Ivanovich’s apprentices, as well as myself, your obedient servant - people who have been working all along to have your project realized... Chirkov wants to have his work estimate enclosed herewith - I believe this craftsman is more reliable than the others...

I’ve talked with [Vladimir] Beklemishev about the bust - certainly, he gladly agreed to fit the [Kuindzhi] bust into the column and asked to tell you that he’s prepared to help you with that.

I’ve talked about the outline drawings for the mosaic with [Nicholas] Roerich[11] and he will certainly make good on his promise.”[12]

Shchusev set about completing the memorial at about this time. He eliminated the lateral wings of the wall that had featured in his out-of-competition design and increased the width and height of the central section, thus giving the structure a more impressive look. The stone canopy over the artist's bust became the dominant motif. Shchusev's sketches show that he contemplated filling some sections of the memorial with imagery carved in stone. The concept and colour scheme of the mosaic changed too, the imagery of a birch tree grove replaced with the theme of intertwined vines evoking Leonardo da Vinci's ornamental ceiling painting for the “Sala delle Asse" at the Sforza Castle in Milan, with the inscription moved to the bust's pedestal. Shchusev sent his new version of the design - the third, not taking into account the pre-competition and out-of-competition sketches - to the Society: according to him, he planned, after securing the Society's approval, to hire the sculptor Sergei Evseev to produce the model of the memorial.[13] Returning the technical drawings to Shchusev in April 1913, Frolov wrote:

“Dear Alexei Viktorovich.

... I hereby wish to communicate to you (officially) that most members [of the Society] favoured the version without the ornamentation on the pediment. Of course, the proposals included some extraordinary ones, but in view of their lack of reason they do not merit any mention.

And now I ask you not to delay the production of the model and send your final version directly to the Society...

I have shown your design to Nicholas Roerich, and he enthusiastically confirmed his willingness to create an outline drawing for the mosaic in the niche... He hopes that there will be no more reconsiderations on your part and will create a design applying the measurements from your drawing. I got in touch with Roerich so quickly because he is leaving the country soon...”[14]

Receiving the letter, Shchusev communicated to Roerich:

“Frolov writes that you'll be producing sketches for the Kuindzhi memorial. I've created an outline but will be making it simpler and adding new details although the size of the niche remains the same. To get an idea of the rhythm, look at da Vinci's tree at the Sforza Castle, it was printed in the Volynsky publication."[15]

As Frolov mentioned, Roerich left for Paris in May to work on theatrical productions, and from Paris he travelled to Kislovodsk, where he was to undergo a treatment and stay for some time, almost until mid-July. During that period he did not work on the new outline drawing for the mosaic. Shchusev meanwhile introduced some changes. Taking them into account, Evseev accomplished an architectural model, which the architect wanted to use to test his design.

However, this version would not to be the last, either. On July 13 1913, Maria Dillon wrote to Shchusev:

“Dear Alexei Viktorovich.

First of all, I beg your pardon for this unexpected intervention, but it seems to me that I need to bring an issue to your attention before it is too late. It is this:

On July 11, I attended the service of remembrance for the late Kuindzhi, whence, in the company of several artists, I went to have a look at the model of the Kuindzhi memorial that you have designed. I remember perfectly well the sketch that I saw in your studio, it appeared to have fine proportions; in addition, I remember that you envisioned a fairly thin wall and a shallow niche. Well, what I saw in the small model, in my opinion, has nothing to do with your sketch - first of all, because the wall there is very heavy and the niche is very deep. May I assure you that I wouldn’t dare to intervene in your affairs were it not for my Kryzhitsky memorial, which is certain to be disadvantaged by the Kuindzhi monument when it is put in place next to it - as the matter stands, the large protrusion from your wall will completely hide from view the Kryzhitsky tombstone.”[16]

Shchusev must have promised to do all he could, since in her next letter Dillon was already expressing her thanks: “I owe a debt of gratitude for your beneficence and for the joy I felt when I saw that I was right about you. May God help you bring your work to a successful conclusion."[17]

After this the architect produced the next version - his fourth - of the headstone's design. This one had the thinnest possible wall, a different shape to the pediment, with the inscription placed to the left of the arch. He enclosed with this version two additional variants: one, in accordance with the Society's proposals, had a minimal amount of carved stonework (only a cross and two doves on the pediment); another had carved stonework all over the top. He needed ornamentation to link the mosaic and its framing compositionally. Evseev produced a new wood-and-gypsum model based on these sketches.[18]

In late August, Shchusev left for Italy to oversee the construction of the buildings he had designed there - the Church of St. Nicholas in Bari and the Russian Pavilion in Venice. Upon his return in September, he reminded Roerich about the assignment:

“Dear Nikolai Konstantinovich!

I have just returned and have received your letter. Frolov writes that [he wishes to] see the fresco of your own making in the model, and if you choose wood as the material, don't copy Leonardo - something Russian is needed - a birch tree, and you have the talent to produce a fine semi-landscape, semi-ornament against a golden background. As for me, I'm certain that you're the one to do the work, and I wouldn't take this assignment for anything; if you select the first version, although it's too Russian, too northern for A.I. [Kuindzhi], I think it should be realized anyway..."[19] And a little later: “And now about the Kuindzhi memorial. What have you decided? Think about wood, the things that you and I have been designing together have come off well, hold on to this principle."[20]

In Autumn 1913, Roerich created a new outline drawing for the mosaic, featuring the so-called “Tree of Life" with golden leaves and blue flowers against a black, starry sky. The crown of the tree is flanked by the moon and the sun, which symbolize the Tree's immortality within the stream of ephemeral time. At the tree's root there is a stylized, almost icon-like, hilly landscape with churches and low-growing plants, above which it towers. At the top of the tree is a nest, with a bird protecting its chicks from a snake that has sneaked into it.[21]

Some elements of the composition echo the murals that Roerich was producing at that time for the Chapel of St. Anastasia in Pskov, also designed by Shchusev, and for the Church of the Holy Spirit in Talashkino. Laden with symbolism, the imagery of the mosaic is perhaps rooted not only in the Bible. The Tree of Life portrays the grandeur and unfading importance of Kuindzhi's art and personality. The golden smalt is probably an allusion to the origin of the artist's surname (kuyumdzhi means “goldsmith" in Turkish: the artist's grandfather had been a jeweller). The black sky references his famous night landscapes, while the struggle with the snake shows how Kuindzhi took care of his students. As Roerich recalled: “Kuindzhi knew how to defend those who had been wronged. The students at the Academy often didn't know who it was that courageously rallied to their defence. 'C’mon, keep your hands off the young.’ Kuindzhi showed his strong commitment when Grand Duke Vladimir and Count Tolstoy suggested he should immediately hand in his resignation for defending students."[22]

The sketch also features a dozen small birds around the Tree, reminding us about Kuindzhi's love for animals and birds, as recalled by Roerich in his memoir: “His private life was unusual and isolated, and only those students who were closest to him knew the depths of his soul. At noon on the dot, he would go up to the roof of his house and, as soon as the midday gun was fired from the fortress rampart, thousands of birds would flock to him. He would hand-feed them, all these countless friends: doves, sparrows, crows, jackdaws, seagulls. It looked like all the birds of the capital had flocked to him, covering his shoulders, arms and head."[23]

The sketch submitted to the Society, however, received a negative response, about which Roerich complained to Shchusev in November of the same year:

“Dear Alexei Viktorovich!

With the Kuindzhi Society, I don't know what to do: my project was met with criticism so harsh there that now, for all my desire to change anything, the changes will look like they have been done in response to the shouting of people like Genteev... I just don't know!

I'm simply looking in amazement at this despicable Society which wrecks and banishes everything!"[24]

After this Shchusev adopted a less cooperative stance, determined to see the project through to its completion without further consultations with the clients:

“Dear Nikolai Konstantinovich. I received your letter - I think that in matters concerning the Kuindzhi memorial I'll be keeping in touch only with you and Frolov; the Society does not need to look into it any more. Frolov is writing from Ravenna that he's on his way back already, and I'm thinking - give him the sketches, let some of your assistants produce a larger image on carton, and we'll call it a day. I've never seen anyone from the Society during my visits, there is no need to discuss the memorial anymore."[25]

However, Roerich made some concessions, mostly formal ones, soon writing to the architect: “I've removed birds from the sketch of the memorial; replaced them with flowers."[26] This phrase from the letter is interesting because it indicates that the above-mentioned sketch was changed. Perhaps the motif of birds had been much stronger in previous versions. Having tried Roerich's sketch on the model, Shchusev decided to go ahead with the variant featuring a more complex ornament on the pediment.

Alexei SHCHUSEV. Sketch for Arkhip Kuindzhiʼs memorial. Final version with a carved pediment. Facades. 1913

Lead pencil, watercolour, bronze paint on tracing paper. 21.5 × 67 cm. Private collection. First publication

The production of the memorial began in Spring 1914, with Shchusev drawing patterns - full-sized individual details - at the same time. Evseev was told to use these patterns, producing stucco models of fragments of carved stonework in order to make things easier for the stone-carver. The imagery of the carved stonework echoes the themes in the mosaic panel - birds and animals woven into a floral ornament. The architect meanwhile introduced his final changes, removing the wordy inscriptions in ornate fonts from the front of the monument, replacing them with a crucifix, and leaving only a brief inscription “Kuindzhi", in plated irons letters, on the pedestal. He placed the artist's name and the dates of his birth and death on the reverse of the monument.

The main part of the monument was made of grey granite, its foundation of pink granite. The artist's portrait statue, cast from Beklemishev's bust with only slight alterations to its lower section, was made at Karl Robecca's bronze-casting workshop in St. Petersburg. From the out-of-competition version onwards, the architect had been proposing to highlight the pediment under the bust with elements of red. The pediment was manufactured from unique polished Shokshinsky quartzite by the end of September 1914, and the base was made of black gabbro.

The solemn unveiling ceremony took place on November 30 1914, in the presence of all those who had been involved in the monument's creation, whom the Society's members presented with artfully designed formal letters of gratitude. In 1952, Kuindzhi's remains, together with the memorial itself, were transferred from the Smolensky Cemetery to the Necropolis at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra (Monastery), the resting place of prominent Russian cultural figures.

The Kuindzhi memorial is among the best, as well as the most famous works that Shchusev created before the 1917 Revolution, and a good example of one of the most important components of his artistic creed, the synthesis of the arts. Working in close cooperation with artists and sculptors, the architect was determined to obtain from them artistic solutions that would fit his architectural forms. Comparison of Roerich's final mosaic with Shchusev's earlier tracing-paper sketch is striking: for all the originality of the theme and details, the artist was guided by the composition and scale of the picture set out by the architect.

Shchusev would exploit many of the discoveries he made while working on this memorial in another unique project, the symbol of an entire era - the Lenin Mausoleum. Such formulae include combining stone blocks of different colours and textures, together with mosaic (the decorative panels in the Mausoleum's funeral hall were also produced by Frolov), and the laconic expressiveness of the lettering. Shchusev's mastery is unquestionable: as he moved from one version to the next, taking into account the suggestions of clients and colleagues alike, he brought the final form of his tribute to Arkhip Kuindzhi to perfection.

- Open letter from Vladimir Beklemishev and Valentin Volkov to Alexei Shchusev. Undated (November 1912?). Private collection, published for the first time here.

- ‘Chronicle of Russian Arts’. Supplement to “Apollo” magazine. 1912. Nos. 8-9, April-May. P. 115.

- The competition was advertised in the periodical “Zodchy” (Architect), published by the St. Petersburg Imperial Society of Architects. “Zodchy”, 1912. No. 23, June 3. P. 247.

- For Dillon’s project, see: ‘The Russian Museum Presents: Maria Dillon’ / “Almanac”. Issue 243. St. Petersburg, 2009. P. 36.

- For Beklemishev’s project, see: ‘The Russian Museum Presents: Vladimir Beklemishev’ / “Almanac”. Issue 325. St. Petersburg, 2011. P.77.

- “Zodchy” (Architect), 1912. No. 50, December 9. P. 505.

- Alexei Shchusev letter to Nicholas Roerich, dated January 7 (1913?) / Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 44. Item 1521. Sheet 1. The letter is mistakenly dated 1910, although the information in it suggests it was written in 1913.

- Photographs of Kuindzhi’s gypsum and marble portrait statues were printed in ‘The Russian Museum Presents: Vladimir Beklemishev’ / “Almanac”. Issue 325. St. Petersburg, 2011. Pp. 48-49.

- Pavel Nestorovich Chirkov (?-?) was a stone-carver (?) and proprietor of the “A. Barinov and Successor Pavel Chirkov” store that sold granite and marble objects produced in a St. Petersburg workshop that Chirkov owned. The company also owned a granite quarry in Finland. Chirkov contributed to others of Shchusev’s projects: the second version of Pyotr Stolypin’s white marble gravestone (1913, demolished) and the Gorchakov family burial vault with a chapel (1916, unrealized).

- Vladimir Alexandrovich Frolov (1874-1942) was a mosaicist, like his father, Alexander. In 1894-1897 he studied at the painting department of the College of Arts under the aegis of the Academy of Fine Arts. In 1900 he took charge of a mosaic workshop, producing mosaics for various buildings that Shchusev designed: the Troitsky (Trinity) Cathedral at the Pochayiv Lavra (Monastery) (1910-1911), the Pokrovsky (Intercession of the Theotokos) Church at the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent (1911), and the funeral hall of the Lenin Mausoleum (1929-1930).

- An “outline drawing” is a professional term used by mosaicists - it refers to a detailed sketch, a drawing with the full-sized image to be reproduced.

- Vladimir Frolov letter to Alexei Shchusev, March 4 1913. Private collection, published for the first time here.

- Sergei Alexandrovich Evseev (18821959) was a sculptor and stage designer. In 1904 he graduated from the Stroganov School of Arts and Crafts, and in 1908 took charge of the stage design workshops in St. Petersburg. He made models for Shchusev’s designs, including the Church of St. Nicholas in Bari (1912-1913) and the Kazan Railway Station in Moscow (1914-1917). In 1926, teaming up with the architect Vladimir Shchuko, he created a statue of Lenin that was erected near Leningrad’s Finland Station, and in 1934 he produced portrait statues of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, placed in the garden at the former Smolny Institute.

- Vladimir Frolov letter to Alexei Shchusev, April 16 1913. Private collection, published for the first time here.

- Alexei Shchusev letter to Nicholas Roerich, April 17 1913. Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 44. Item 1523. Sheet 1.

- Maria Dillon letter to Alexei Shchu- sev, July 13 1913. Private collection, published for the first time here.

- Maria Dillon letter to Alexei Shchusev. Undated (July 1913?). Private collection, published for the first time here.

- Evseev’s model of the final version of the Kuindzhi memorial is held at the Russian Museum (wood, gypsum, 47 x 52 x 58 cm). The mosaic in the model’s niche was probably designed by Nicholas Roerich. The photograph of the model was published in ‘The Russian Museum Presents: A Forgotten Russia’ / “Almanac”. Issue 145. St. Petersburg, 2006. P. 101.

- Alexei Shchusev letter to Nicholas Roerich, September 27 (1913?) / Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 44. Item 1531. Sheet 1.

- Alexei Shchusev letter to Nicholas Roerich. Undated (October-early November 1913?) / Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 44. Item 1536. Sheet 1.

- Roerich created an identical drawing of the nest for an emblem of the “Circle of the Young’ (1906?). It was printed in Sergei Gorodetsky’s collection of poems.

- Roerich, Nicholas. ‘Kuindzhi: On the 30th Anniversary of His Death’. In: “My Life”. Minsk, 2010. P. 225.

- Roerich, Nicholas. ‘Kuindzhi’s Studio’. In: “Set the Hearts Alight”. Moscow, 1990. P. 75.

- Nicholas Roerich letter to Alexei Shchusev, November 5 1913. Private collection, published for the first time here.

- Alexei Shchusev letter to Nicholas Roerich. Undated (November 12 1913?) / Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 44. Item 1533. Sheet 1.

- Nicholas Roerich letter to Alexei Shchusev, November 19 1913. Private collection, published for the first time here.

Lead pencil, watercolour, bronze paint on tracing paper. 34 × 40 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil on tracing paper. 41 × 20 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil on tracing paper. 19 × 36 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil and ink on paper. 32.5 × 48 cm. Private collection. First publication

Charcoal, colour pencils, gouache on paper. 31 × 49 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil, colour pencils, ink, watercolour, gouache, bronze paint on paper mounted on cardboard. 49 × 64 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil, colour pencils, watercolour, gouache, bronze paint on paper mounted on cardboard. 49 × 63.3 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil, watercolour, gouache, bronze paint on tracing paper. 40 × 35 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil, watercolour, gouache, bronze paint on paper mounted on cardboard. 37.5 × 50.5 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil, watercolour, gouache, bronze paint on paper. 39 × 29.3 cm. Private collection. First publication

Charcoal, colour pencil, watercolour on tracing paper. 69 × 41 cm. Artist’s inscription on the upper left-hand side: If the niche is given in a flat pattern, the whole drawing will be wider. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil on paper. 13 × 9 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil, watercolour, bronze paint on tracing paper. 25 × 49 cm. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil, gouache, bronze paint on paper. 50.2 × 34.5 cm. Russian Museum

Lead pencil, gouache, bronze paint on paper. 50.2 × 34.5 cm. Russian Museum

Lead pencil, gouache, bronze paint on paper. 50.2 × 33.8 cm. Russian Museum

Gouache, bronze paint on cardboard. 65 × 45.3 cm. Russian Museum

Photograph by Alexei Shchusev. On the right is Konstantin Kryzhitsky’s memorial. Private collection. First publication

Photograph. From “Iskra” (Spark) newspaper, 1912, No. 46

Lead pencil, ink, bronze paint on tracing paper mounted on cardboard. 15.5 × 38.5 cm. Artist’s inscription on the lower left-hand side: The type weight could be larger, the colour of dark bronze. Private collection. First publication

Lead pencil, watercolour on paper. 50.7 × 33.7 cm. Private collection