St. Anastasia Chapel in Pskov. AN ARTISTIC COLLABORATION BETWEEN ALEXEI SHCHUSEV AND NICHOLAS ROERICH

To dear Alexei Viktorovich Shchusev, as a token of my heartfelt admiration for his truly monumental talent, which will be considered in the future as one of Russia's jewels, in memory of our common thoughts, aspirations, hopes and faith, yours truly and sincerely, Nicholas Roerich.

November 15, 1913Nicholas Roerich's dedication in his "Collected Works”, 1914

A small but unique creation by Alexei Shchusev (1873-1949), the St. Anastasia Chapel in Pskov is one of the few church buildings designed by Shchusev to have survived to the present day in Russia, and its murals are among only a handful of surviving works of public art by Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947). Neither artists’ biographers have written much about this landmark, the construction and decoration of which was an important milestone in their artistic collaboration. Despite its significance, in the Soviet period, the chapel suffered serious losses and the deformation of its original appearance. Only now - given the opportunity to study the previously unpublished archival materials, photos taken before the Bolshevik Revolution and technical drawings - can researchers trace the history of the chapel’s creation, compare its architecture and decor, and gain a better understanding of its creators’ vision.

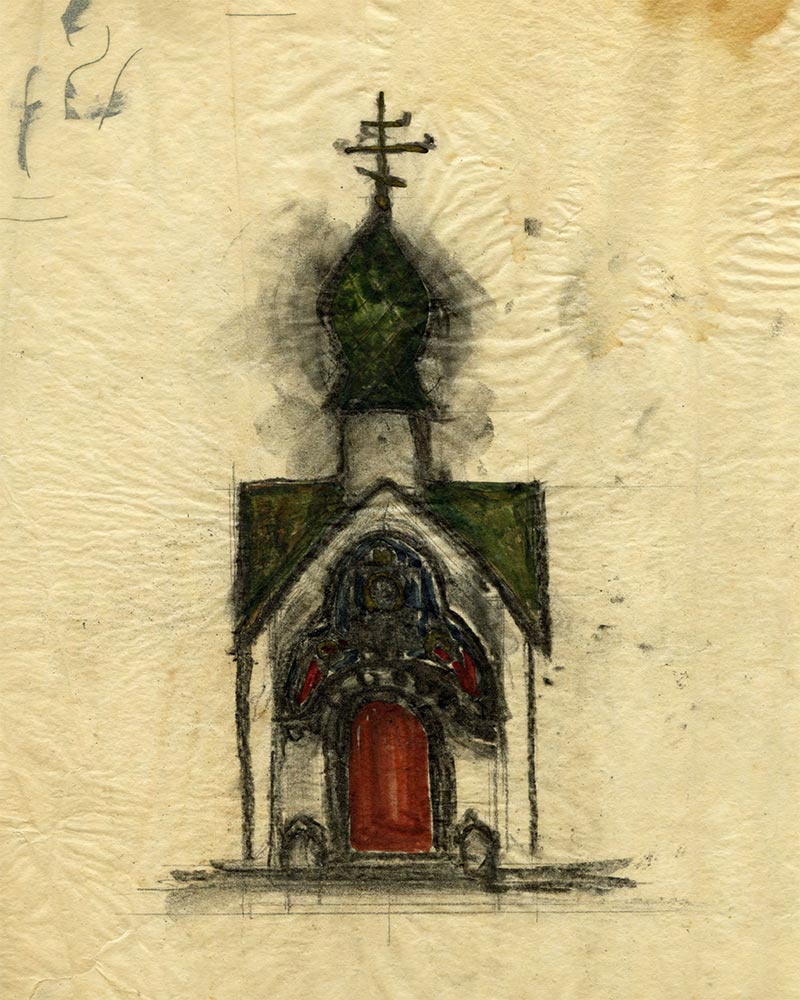

ALEXEI SHCHUSEV. Sketch of the St. Anastasia Chapel in Pskov. Initial variant. Façade. 1910-1911

Charcoal, watercolour, bronze paint on tracing paper. 33.3 × 27.7 cm

Private collection. Published for the first time

The artistic paths of Shchusev and Roerich crossed many times. Of nearly the same age, they first met as students at the Russian Academy of Fine Arts, where both visited student gatherings at Arkhip Kuindzhi’s house. Both graduated from the Academy in 1897 and continued their artistic training in Paris[1]. In the spring of 1906, Roerich was appointed director of the Painting School run by the Imperial Society for Encouragement of the Arts. Reorganising it, he first focused on its teaching staff, hiring Ivan Bilibin, Vasily Mate, Dmitry Kardovsky, Sergei Makovsky, Vladimir Shchuko and Shchusev. A shared interest in archaeology and academic study of Old Russian architecture also drew them closer together, but it was through working on common projects that they became friends. Roerich reminisced later:

As for architects, who even elected me a member of their society's board, my friendships with them were formed around our construction work. Then came Shchusev - one of the most remarkable architects. Teaming up, we produced the mosaic for the Pochaev monastery, the chapel for Pskov.[2]

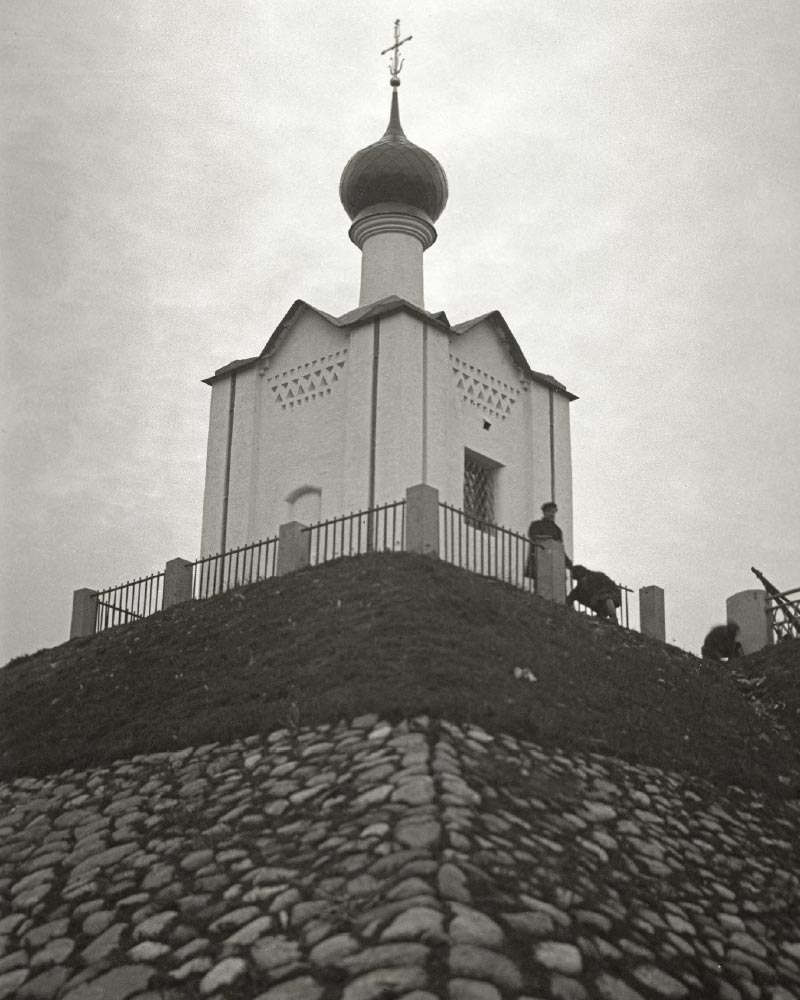

The St. Anastasia Chapel in Pskov. View of the south and east façades September-October of 1911.

Photograph by Alexei Shchusev. Private collection. Published for the first time

In 1906, Shchusev invited Roerich to take part in decorating a church building he was working on as an architect: the Holy Trinity Cathedral at the Svyato-Uspensky Pochaevsky Monastery. Initially, it was to be a major commission: designs of mosaics for two portals, icons for the central section of the iconostasis, and frescoes covering part of the walls. Financial difficulties at the monastery, however, pared all this down to just one mosaic on the southern fagade, “The Mandylion and the Holy Princes”, which was accomplished in 1908-1910. Concurrently with the cathedral in Pochaev, Roerich was also working on another project, which he had started a little earlier: decorating two big churches designed by Vladimir Pokrovsky, who was, like Shchusev, a prominent champion of the Russian Revival style.[3] It was those years that shaped Roerich’s approach to religious art and his predilection for certain themes that he would address in his spiritual compositions: the heavenly host and earthly warriors; the Mother of God, protectress of the human race; a Christian understanding of the cosmos. Drawing on Old Russian and Byzantine imagery, the artist formed his vision of the church’s interior - unique, but also in keeping with the Orthodox Christian canon. This exploration should have reached its climax in mural paintings and mosaics commissioned for Princess Tenisheva’s Church of the Holy Ghost in Talashkino. The artist was working on them from 1908 to 1914, until the First World War brought everything to a standstill. It was in the middle of this project that Roerich was offered by Shchusev several new commissions, which included murals for the St. Anastasia Chapel in Pskov.

The Mandylion and the Holy Princes. A mosaic by V. Frolov (1910) based on a sketch by N. Roerich (1908). The southern narthex of St.Trinity Cathedral at the Svyato-Uspensky Pochaevsky Monastery.

Photo: S. Koluzakov. 2013

The history of the present-day chapel is quite noteworthy. Once, there used to be a floating bridge across the Velikaya River, with one end near the (Paromenskaya) Assumption Church. When it was decided, in 1909, to replace the old bridge with a permanent one, it became clear that the low shoreline needed to be raised to the level of the Market Square in the town’s centre. The earth-fill site happened to be near a chapel dedicated to Holy Martyr Anastasia the Roman[4], which was built in 1710 in fulfilment of the pledge made in the time of the pestilence,[5] and stood at the point where the road to Riga began. On August 25, 1909, a deputy of the Bishop of Pskov wrote a letter to the engineer in charge of the bridge construction project Leonid Belyavin[6] with the following request:

Near the site where the earth-fill works are in progress [...] there stands a chapel dedicated to the Holy Martyr Anastasia—it has been there since time immemorial and belongs to the Paromo-Uspenskaya [Assumption] Church of the City of Pskov. The church's clergy and warden have apprised us that, when the bridge is built, this chapel will remain at the foot of the earth bank, so 1) water, mud and refuse will slide down the slope and accumulate on the land around the chapel; 2) the site around the historical chapel will become a dumping ground; 3) on account of the chapel's surroundings a repair that the church cannot afford would be necessitated every year. and 4) presently, as the chapel is continuously exposed to the fumes emitted by the steam engine employed to build the stone piers for the bridge, the plaster on its walls is becoming moist and peeling, and cracks are appearing in them. In view of the above, the priests with their warden and I, for my part, humbly ask Your Honour, if you would deem it appropriate, to issue... an order to take down this chapel, with the consent of the Bishop's office, and place up at the top of the earth bank a new chapel (on the same site), at least a small one, dedicated to the Holy Martyr Anastasia, using the funds made available to you for the construction of the bridge...[7]

The bridge construction committee reviewed the clergyman’s request, found it legitimate and, most importantly, decided that building a new church would make more sense financially than the construction of a new protective breast wall near the old one, as previously planned. The engineer Belyavin personally produced technical drawings and specifications for a breast wall, which was put in place together with the foundations for the chapel (the dimensions of the foundations were probably set with a view to preserving the old iconostasis). Belyavin also produced two versions of the chapel’s design, although neither of them was approved by the construction department of the Pskov Governorate.

On October 15, 1910, Sergei Zubchaninov, chairman of the Pskov Gover- nate's executive council, wrote to the architect Shchusev:

My dear sir,

[...] With regard to the desire to build a chapel small in size but grand in design, distinguished by its great artistry, worthy of Pskov's other surviving architectural landmarks, all my attempts to obtain a good project have failed.

Igor Immanuilovich Grabar has advised me that you, Alexei Viktorovich, are the only person capable of carrying through the laborious undertaking of producing a design for the chapel in the spirit of Pskov.

Begging your pardon for not having the pleasure of knowing you in person and aware that you are busy beyond all measure, I nevertheless ask you - please aid the Committee in its undertaking and produce at least a rough sketch of the chapel. I dare not bother you with a request to take care of the overall design, technical drawings of details and the estimate of construction costs, so I ask you most earnestly to assign these tasks to someone else, with all the expenses to be borne by me.

For your reference, I am sending you a draft of the bridge's design, with indication of the proposed site for the chapel. This draft also indicates the size of the foundation built for it.[8]

A report Belyavin filed on March 15, 1911, tells the story of the ensuing negotiations with Shchusev:

Shchusev in January this year said he would agree to take charge of designing and building the chapel provided that he is paid 1) 500 rubles for the design, 2) 150-200 rubles for travel, 3) 100-150 rubles for an assistant at the site - 750-850 rubles in total. The committee at its meeting on February 26 decided that the chapel, built on top of the breast wall at the entrance to the bridge, should be an adornment of the surroundings, so its members deemed Mr Shchusev's conditions acceptable and asked me to thrash out with him the details of the agreement and the overall costs of the chapel... In response to my inquiry, Shchusev, in a letter of March 11 of this year, confirming his agreement to accept this undertaking on the above terms, put the cost of the chapel's construction at 2,500-3,500 rubles. So, the most it will cost is 850+3000=3,850.[9]

Based on the documents reviewed here, late 1910 to early 1911 can be considered the date when the chapel project was officially commissioned from Shchusev. As the foundation was already built, Shchusev had to work within pre-set parameters: a site already assigned, the dimensions already established and the uncanonical decision to build the altar wall facing south already taken, although historians would later ascribe the idea to Shchusev himself. Besides, the initial agreement was that no interior decor (besides a simple plaster finish) would be required.[10] The architect at that time was mostly preoccupied with the completion of his “big-ticket” projects: the Pokrovskaya [Intercession of the Theotokos] Church of the Pokrovskaya Cathedral at the Marfo-Mariinskaya Convent in Moscow (1907-1911, 1914), the Church of St. Basil in Ovruch (1904-1911) and the Troitsky [Holy Trinity] Cathedral in Pochaev (1904-1912). These projects influenced the chapel's design in different ways, as it was while working on these buildings that Shchusev developed his original take on Russian architecture and conveyed his inimitable vision of the Russian Revival style. There is also an easily detectable kinship with another of his creations, which he had started to build a year previously - the Church of the Most Gracious Saviour in Natalievka (1910?-1913). Thus, the sketches and technical drawings for both buildings are placed side by side in his albums and exhibit common features.

Shchusev’s initial sketches for the St. Anastasia Chapel show a building imbued with the spirit of Art Nouveau, its elongated cupola the final touch to a silhouette that reaches for the heavens. The portal is accentuated with a large mosaic panel, similar to the Pochaev cathedral and the early versions of the church in Natalievka. This compositional arrangement did not, however, satisfy the architect. He continued searching for an architectural solution, drawing inspiration from austere forms of Pskov’s ancient landmarks. Producing one sketch after another, Shchusev changed the cupola’s proportions, making it heavier, and elaborated the geometrics of the roofing. The framing of the portal became significantly plainer and the mosaic was replaced with a small icon in an icon case.

Researchers have not seen the final version of the chapel’s design - most likely it did not survive - but drafts from the architect’s family archive allow us ample opportunity to trace the further evolution of Shchusev’s vision. In the spring of 1911, Shchusev came to Pskov to see with his own eyes the complex architectural landscape into which the chapel was to be fitted, close to Pskov’s ancient Krom [or Kremlin] and historic centre. His notepads and the photos he took then feature the nearby Paromenskaya Church of the Assumption. Later, the architect began to see the chapel and the neighbouring church as part of an organic ensemble. This is corroborated by the similarity between the form of the chapel’s cupola in the final version of the draft and the cupolas above the aisles of the Paromenskaya church, as well as by the similar brick ornament on the chapel’s fagade. Eager to preserve the gracefulness of previously established proportions, Shchusev opted for a tall pyramidal roof with tented tops cutting into the fagades and the angles of the walls accented with the vertical lines of doubled lesenes.

Shchusev went on to produce detailed drawings of individual elements of the building. As numerous sketches confirm, he spent much time working on the front door and the icon case above it, as well as the cupola with the cross. His vision of the door alternated between a very simplified version with conspicuous superimposed elements and an iron-plated door with stylised chased floral decoration, like the western door of the Pokrovskaya Church at the Marfo-Mariinskaya Convent. Eventually, he opted for plain door panels, like those he designed for the chapel with gatehouse at the Marfo-Mariinskaya Convent and the Church of St. Basil in Ovruch. He elaborated the design of wrought-iron grilles for the round-headed windows in the side walls. The exterior of the altar wall was to be decorated with a builder’s plate. The main highlight in Shchusev’s chapel design, however, was the cupola, covered with iron scales and crowned with an intricate and elegant wrought-iron cross. The design of this cross was literally borrowed from the sketches for the church in Natalievka, although, when completed, that church in fact had a different cross. For every element, full-size technical drawings were produced. In April 1911, Shchusev was offered an additional assignment - designing a fence for the site of the chapel site near the bridge: a grille whose elegance would match that of the chapel.[11]

The laying of the foundation stone for the chapel took place on August 5, 1911. Just a few days later, the following record appeared in one of Belyavin’s reports about the Velikaya River bridge construction: the building of the St. Anastasia chapel has begun and will be completed in the second half of September.[12] The walls were built of limestone and brick and the dome of reinforced concrete. The walls were then plastered and painted white. Shchusev is known to have initially planned to produce a new iconostasis for the chapel to accommodate the already existing icons, because the old Baroque iconostasis was stylistically out of character with the new architecture. Grigory Osipovich Chirikov was asked to evaluate the condition of the old iconostasis and the possibility of its preservation.[13] Shchusev himself was then living and working in St. Petersburg, but his assistant Mikhailov was working on the site in Pskov.[14] He kept Shchusev updated on construction progress and wrote on August 23, 1911:

Dear Alexei Viktorovich,

I have been told that it remains uncertain whether the old iconostasis should be installed or a new one produced: the construction costs need to be all totalled up, then it will be clear how much money we have available. Nonetheless, yesterday I sent a cable to Chirikov, asking him to come and inspect the iconostasis and tell us about his terms. We learned from his cabled reply that he was in Ovruch. We have decided to do without backstays, as the walls are very firm; the vault - thanks to a thick network of beams, the quality of the concrete, and horizontal abutments - will not produce any lateral pressure. We did not manage the three-centred arch over the window [...] so we had to make do... with a little decorative arch the size of half a brick, thanks to this we could make a convenient air duct and keep intact the right appearance of the window inside the chapel. [...] The carpenter produced the parts of the cupola using the full-size drawings and will do the assembling after completing the framework. I have communicated all that you wrote in your letter to Leonid Petrovich. Yours respectfully and faithfully, Vl. Mikhailov.[15]

The letter also makes clear that the structure of the reinforced concrete vault did not permit the builders to produce round-headed windows according to Shchusev’s design and the architect had to rework the technical drawing of the window grille.[16] When Chirikov came to Pskov, the decision was taken to proceed with the old iconostasis, and on August 30, 1911, he produced a cost estimate for the renovation and artistic work:

Renovating the old 18th-centiry two-tier iconostasis, adding on top. a carved icon case and an icon. Cleaning the frame and the woodwork of the iconostasis down to the wooden base, identifying the degrees of coloration and gilded and silver-plated spots along the way; trimming damaged woodwork and applying the gesso primer for painting and gilding; applying gilt and paints in the original manner. [...] Painting one new icon for the new icon case. [...] Producing... three hanging incense burners for candles with brackets. [...] In addition to them, three icon lamps. One hanging lamp for the centre of the chapel. [...] Fresco-secco painting the vaults in the chapel, as well as all of the walls, as shown in Academician A.V. Shchusev's design: 600 rubles. Academician A.V. Shchusev's design and oversight: 200 rubles. All of the above, in total: one thousand, six hundred and eighty-five 1,685 rubles.[17]

The iconostasis from the chapel is believed to have been lost for good, although there are unique photos, taken immediately after Chirikov’s renovation in 1912-1913, which show us what it looked like. The iconostasis from the old chapel had two tiers: local saints and feasts. The local saints tier featured such icons as “St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker”, “St. Anastasia”, “Select saints [including, inter alia, the aforementioned St. Anastasia and St. Nicholas] with the Feast of Resurrection and the Old Testament Trinity”. The heterogeneous mixture of local icons suggests that the iconostasis in the 18th century was composed of relics then kept in the chapel. The feasts tier included five icons: “The Annunciation”, “The Transfiguration”, “The New Testament Trinity”, “In Thee Rejoiceth...”, and “The Assumption”. All of the same style and size, they were probably produced especially for the iconostasis. Above the feasts tier, in the centre, Chirikov placed a 19th-century icon “The Lord of Sabaoth” and, above it, a crucifix.

NICHOLAS ROERICH. The Mandylion. Sketch of the mural of the north wall in the St. Anastasia Chapel. 1913

Lead pencil and tempera on cardboard. 64 × 47.5 cm. © Russian Museum

Securing a commission for the chapel’s interior decor was very important for Shchusev. To back up Chirikov’s estimates, he personally wrote to the engineer in charge of the bridge construction:

Dear Sir [Leonid Petrovich Belyavin],

Considering that... the construction of the St. Anastasia chapel to my design is nearing completion, whereas inside it... remains without any finish, painting and iconostasis, and so it follows that the clergy of the Paromenskaya Church would have to fill the chapel with holy objects of their own making and, therefore, compromise the integrity of the austere old style in which the chapel is designed... I take the liberty of addressing you in my capacity as the creator of the design and asking that you solicit the estimated lacking sum that would make possible the full completion of the chapel's decoration in the spring of 1912, and that the chapel be handed to the bishopric only when this task is completed. I dare hope that this is the only way to ensure the consistency of the abovementioned chapel's austere appearance not only outside, but inside as well.[18]

When completed, the bridge was opened for vehicles and pedestrians on October 30, 1911, after a procession of the cross and a consecration ceremony. Emperor Nicholas II gave his approval to name the bridge Olginsky, in memory of Grand Princess St. Olga of Kiev, Equal of the Apostles, who, as the legend goes, was born near Pskov. In the autumn, Shchusev again came to Pskov to personally oversee the completion of the final works on the chapel. The photos he took capture the installation of the fencing near the chapel’s eastern, western and southern walls, as well as the hanging of the lamp in front of the icon in the niche on the front wall. On the icon, which was probably painted by Chirikov especially for the chapel, we can discern the silhouette of St. Anastasia with a scroll in her left hand and a crucifix in her right. The altar wall features a white stone memorial plate, fashioned to Shchusev’s design, with this inscription in an ornate Cyrillic script: “In the summer of 7419 Anno Mundi and 1911 Anno Domini, during the reign of the most pious emperor Nicholas II Alexandrovich, this holy chapel dedicated to the Holy Martyr Anastasia was built with funds provided by the Board of Inland Waterways and Highways, under the supervision of the engineer in charge of construction of the bridge across the Velikaya River L.P. Belyavin,, as well as his assistants V.D. Leontiev and V.P. Tikhomirov, with participation of members of the Construction Committee and its chief engineer V.K. Orlovsky, as well as members of the Board of the Pskov Audit Chamber - I.G. Astreiyn, P.T. Mikhailov, S.I. Zubchaninov, L.B. Kreiter, A.K. Albov, G.D. Gertz and P.D. Batov, under the practical oversight of the auditor A.P. Ogloblin, to the design of Academician of Architecture Alexei Viktorovich Shchusev.” It is notable that the above text does not mention the architect’s assistant, who oversaw the chapel’s construction, but names mostly officers in charge of the bridge’s construction and local officials who approved the project and provided the necessary funds. Perhaps an explanation can be found in the insignificance of Mikhailov’s role in the undertaking and/or in Shchusev’s displeasure over, for instance, the changes to the shape of the window apertures (the architect is known to have always insisted on precise execution of his designs and loathed even the most minute deviations). On November 1, 1911, the Board of Inland Waterways and Highways, heeding Shchusev’s request, approved Chirikov’s estimate and appropriated an additional 2,000 roubles for the chapel’s interior decoration.[19]

In 1912, the construction of the Olginskaya Bridge was nearing completion, and decorative obelisks with lamps were mounted at the entrance points on both sides. In March, the committee in charge of the bridge’s construction reassigned the responsibility for decorating the chapel to the zemstvo [self-government body] of the Pskov Governorate.[20] Shchusev, meanwhile, had again teamed up with Roerich. This time, they were responsible for producing a tombstone for their teacher, Arkhip Kuindzhi.[21] At about the same time, the architect asked Roerich to take part in designing the decor of the Kazan Railway Station in Moscow[22] and the St. Anastasia Chapel. Aware that the artist was busy on the Talashkino project, he promised him a floating deadline for the station’s mural and asked for nothing more than sketches for the Pskov frescoes.

On December 3, 1912, Roerich wrote to Shchusev:

I received your technical drawings for the chapel and will make pictures. It is true that 200 rubles is very little, but let's not talk about it,[23]

and on December 16, the architect responded:

Please, don't take too long with the sketches, we should do the painting in the summer.[24]

This is currently the earliest known document indicating the date when Roerich was offered the commission to decorate the chapel’s interior: the end of 1912. Of most significance is the fact that the church building had been completed by then, so the technical drawings sent to the artist were of a precise, definitive nature. The work on the sketches for the frescoes was finished in March-April 1913, as is made clear in one of Shchusev’s letters:

Now I want to remind you about the chapel; submit your sketches and Chirikov will send you the money right away. Do this before you leave Russia.[25]

(In May, Roerich went to Paris to work on theatre projects.)

In June 1913, Shchusev discussed in his letters to Roerich whether Chirikov should be trusted with the task of painting the frescoes:

I don't know what to do with Chirikov - he is willing to take the assignment, we can pay 200 rubles right away he'll return your sketches, but 200 rubles is too little, 300 is the very least, but what if he botches the job? Maybe you can recommend to him your apprentice at the rate of60-70 per month... he would not mind, write to him. [...] Nesterov scolds me and tells me that Chirikov would make a mess of the paints.[26]

But despite these doubts, Chirikov was given the painting assignment. He carried it out from June to October 1913. Later Shchusev wrote to Roerich:

I wish to update you on the Pskov chapel, relating what Chirikov has told me: the chapel is finished, the iconostasis and everything else are in place, all came off very well and the commission is extremely satisfied because the chandelier is not screwed into the plafond, so the remaining 50 rubles will be sent to you, for your assistants. Besides, I shall tell the zemstvo to send their evaluation report to you. The ornament includes an inscription that Chirikov painted to your design. Chirikov must return the drawings and specs to you.[27]

On November 5, 1913, Roerich replied:

Dear Alexei Viktorovich, Thank you for the news about the chapel; it means that our experience was a success and this settles a lot of our plans for the future. [...] I am certain that you speak well of me. And the paths we follow have so much in common.[28]

The chapel must have been consecrated on October 29, 1913, on the day dedicated to the memory of the saint’s martyrdom.

Regrettably, the surviving frescoes are but a pale shadow of the chapel’s original art. We can get a fuller picture if we look at Roerich’s surviving sketches and the unique photographs taken before the Revolution. In a monograph about Roerich published during his lifetime, the writer mentioned the number of sketches and their style: four sketches for the Pskov chapel murals (in a style close to the canon of 17th-century Russian icon painting.)[29] Two of the sketches (the northern wall and the plafond) are held at the Russian Museum. The whereabouts of the other pieces (the western and eastern walls) are unknown. As for the southern wall (the one with the altar), there were no plans to decorate it with a fresco as it was almost entirely hidden behind the iconostasis.

Roerich’s sketch for the northern wall features, above the entrance portal, the Mandylion [the image of the Saviour “Not-Made-By-Human-Hands”] supported by angels. Below, along each side of the doorway, there are kneeling holy princes, presumably Vsevolod of Pskov and Daumantas of Pskov, heavenly protectors of the city, against the backdrop of a stylised town. An ornamental band stretches beneath their feet. The composition is a milestone in the journey of artistic exploration that Roerich had begun with his previous projects - the mosaics for the churches in Parkhomovka, Pochaev and Talashkino. Painting on the walls to Roerich’s design, Chirikov significantly reduced the size of the sudarium with angels because he had to find his way around the complex geometrics of the wall and the door jambs - something that Roerich did not take into account. For the same reason, above the doorway he painted an ornamental band and seraphs not envisaged in the design.

Roerich’s sketch of the plafond features a blue vault of Heaven, with the Sun, Moon and stars. The Holy Ghost, in the centre, is a dove on a little cloud, surrounded by heavenly creatures - seraphs and cherubs. The artist conveys the Christian understanding of the cosmos - an identical image is also featured above the entrance arch of the church in Talashkino. Painting the plafond, Chirikov faithfully reproduced the sketched image.

In photographs taken before the Revolution, you can catch a partial glimpse of the frescoes on the walls with the window apertures, the sketches for which have been lost. The compositional arrangements are somewhat similar: the windows are flanked with images of full-size angels with fluttering banners in their hands and, over the apertures, there are saints in a round town. Sheep are grazing around the town, symbolising a congregation of believers. An ornamental band extends along the bottom of the walls. As for the floral motifs adorning the door jambs and lunettes, in the same way as they do on the northern wall, it is possible that they did not feature in Roerich’s sketches and were added by Chirikov at his own discretion. These images, however, have different symbolical overtones. On the western wall, the flagstaffs in the angels’ hands are topped with spikes and the ornament on the banner cloth includes an arm carrying a sword appearing from a cloud - a symbol of the Hand of God. The angels rest their other hands on sheathed swords. In the town, we see St. Nicholas of Mozhaysk bearing arms (a nearly exact copy of the image inside the Talashkino church). On the eastern wall, the flagstaffs held by the angels are topped with four-point crosses and the angels hold the flagstaffs in one hand while supporting them with the other; the female saint in the town folds her hands in a prayerful gesture. There is no consensus among the researchers as to this saint’s identity. It would seem logical to presume that this is St. Anastasia. Roerich knew that the chapel would be dedicated to her and thus most likely felt obliged to feature her in the murals somehow. However, the headgear (a crown, a wreath?) over the piece of cloth and the rings at the woman’s temples are not very typical of her canonical image. Roerich could, of course, have drawn on early Western versions of the saint’s iconography.

This would explain the thematic thread of both compositions. They are focused on the protection of the town and the congregation. In the first composition, the protector is the heavenly host, swords in hand; in the second composition, the protection is through prayer.[30] Taken together with the subject matter of the murals on the northern wall and the plafond, you can see that the narrative thread of the chapel’s art is the heavenly protection of the town of Pskov. There are identifiable parallels between the iconography of the frescoes iconography and the composition of the iconostasis. The colour scheme of the wall paintings is based on contrasts of the predominant colours: deep blue and yellow. As for reds, greens, browns, and whites, they are present only as occasional spots.

After the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the St. Anastasia Chapel was, like many other Orthodox churches, dealt severe blows. In 1924, the chapel was closed and was later used as the ticket office for a cinema, as a news stand and as a kerosene store. In the course of these transformations, the building lost its dome drum with the cupola, roofing and door panels, and the frescoes were covered with white paint. The Olginsky Bridge was detonated and rebuilt three times during the Civil and Great Patriotic Wars and, in 1969, it was completely taken apart and replaced with a new structure. As for the chapel, it was designated for demolition as a building “of no artistic or historical value”. The building was saved by Ella Petukhova, head of the Implementation Group for the Protection of Architectural Landmarks, and the architect Natalia Rakhmanina. They were able to prove that the chapel was created by Shchusev and Roerich and have it designated as a protected landmark. Currently, the chapel is a federally protected site and officially a part of the Pskov Open-Air Museum. However, the haste with which the work to preserve the chapel proceeded and the renovation plan was drafted backfired. In the course of relocation to its new site on the bank of the Velikaya River, the chapel’s building was split in two, with the result that fragments of the frescoes (the ornamental belt) were lost and the altar wall is now facing east. Working on the chapel’s upper part (roofing, dome drum and cupola) and entrance door, the renovators ignored Shchusev’s design. The project to remove the white paint and renovate the frescoes began in 1970.[31] The tempera below the white paint turned out to have been severely damaged and to lack its former brightness, the contours no longer crisp. But even in this condition, the architectural forms and the frescoes are a compelling sight. The loss and damage look like the imprint of time, placing this structure on an equal footing with Pskov’s oldest landmarks. In recent decades, the condition of the building and frescoes of the St. Anastasia chapel have again given cause for concern. The landmark needs a comprehensive renovation, which would restore it to its initial appearance.

In Shchusev’s creative career, the chapel is important as one of the fully completed projects that clearly demonstrate the architect’s approach to artistic synthesis and to collaboration with other artistic contemporaries. In this project, Roerich was Shchusev’s kindred spirit - they both were keen students and reinterpreters of Old Russian art, drawing on it to find prototypes for their creations.

- In 1899, for nearly six months, A. Shchusev attended the Academie Julian, a private art school. In 1900, N. Roerich attended the Atelier Cormon.

- Quoted from: N. Roerich, “Friends” [“Druz'ya”] in My Life [Moya zhizn] (Minsk, 2010), p. 28.

- For more detail, see L. Korotkina, “N. Roerich’s Work with the Architects A. Shchusev and V. Pokrovsky” [“Rabota N.K. Rerikha s arkhitektorami A.V. Shchusevym i V.A. Pokrovskim”] in Museum 10. Art Collections of the USSR. Russian Art Nouveau [Muzey 10. Khudozhestvennye sobraniya SSSR. Iskusstvo russkogo moderna] (Moscow, 1989), pp. 156-161.

- For more information about the iconography of St. Anastasia, see P. Chakhotin, “Lives of Other Saints and Martyrs Named Anastasia” in: Sainted Martyr Anastasia. Her Holy Image and Churches in Europe [“Zhiti- ya drugikh svyatykh I muchenits s imenem Anastasia” in: Svyataya velikomuchenitsa Anastasiya. Svyashchenny obraz i khramy v Yevrope], (St. Petersburg, 2010), p. 311.

- “1710. In the spring, the plague, causing many to die every day, was brought from Riga to Narva, Pskov, Izborsk, Porkhov, Gdov and other townships and provinces. [...] In fulfilment of the pledge made during the pestilence, a chapel dedicated to Holy Martyr Anastasia of Rome was built in Pskov on September 1. Names of the builders thereof are entered into the Pskov commemoration book, to be prayed for.” Quoted from Metropolitan Yevgeny (Yevfimy Bolkhovitinov), History of the Principality of Pskov, with the Addition of a Map of the Town of Pskov [Istoriya knyazhestva Psk- ovskogo s prisovokupleniem plana goroda Pskova], part IV (Kiev, 1831), pp. 166-167.

- L. Belyavin (1856-?) was a railway engineer with the rank of a collegiate councillor.

- Request from the priest V. Chernozersky to L. Belyavin, August 25, 1909, Russian State Historical Archive, fund 190, file 8, item 841, sheet 11. Published for the first time.

- S. Zubchaninov’s letter to A. Shchu- sev, October 15, 1910. From a private collection. Published for the first time.

- L. Belyavin’s report to the Board of Inland Waterways and Highways, March 15, 1911, Russian State Historical Archive, fund 190, file 8, item 844, sheet 134. Published for the first time.

- L. Belyavin’s letter to A. Shchusev, February 28, 1911. From a private collection. Published for the first time.

- L. Belyavin’s report to the Board of Inland Waterways and Highways, April 6, 1911, Russian State Historical Archive, fund 190, file 8, item 844. sheet 170.

- L. Belyavin’s report to the Board of Inland Waterways and Highways, August 8, 1911, Russian State Historical Archive, fund 190, file 8, item 845, sheet 170.

- G. Chirikov (1882-1936?) was a distinguished renovator of old Russian icons, expert at the Imperial Archaeological Commission (1910-1917), icon painter and co-owner of the Chirikov Brothers Icons and Iconostases Workshop in Moscow. From 1918, he worked at the Commission for the Preservation and Cleaning of Old Russian Paintings. In 1918, he took part in the cleaning of Andrei Rublev’s “The Holy Trinity" and, in 1919, renovated the icon “The Mother of God of Vladimir”. Shchusev on many occasions enlisted his services for church decoration projects.

- We could not find biographical information about Vl[adimir?] Mikhailov. However, it would be a mistake to relate him to P. Mikhailov, the member of the construction committee in charge of building the Olginsky Bridge, whose name is mentioned among others on the chapel’s builder’s plate. Nor is he related to V. Mikhailov, an architect and Shchusev’s assistant and student, who worked with Shchusev in 1929-1930 and 1944 on the design of the granite mausoleum for Lenin, producing technical drawings.

- V. Mikhailov’s letter to A. Shchusev, August 23, 1911. From a private collection. Published for the first time.

- The full-size drawing of the grille of the round-headed window, which never materialised, is held at the Russian Museum of Applied and Folk Art in Moscow. This is the only surviving full-size drawing made by Shchusev for the St. Anastasia Chapel.

- G. Chirikov’s estimate, August 30, 1911, Russian State Historical Archive, fund 190, file 8, item 846, sheets 44 and 44 reverse. Published for the first time.

- A. Shchusev’s letter to L. Belyavin. September 22, 1911, Russian State Historical Archive, fund 190, file 8, item 846, sheets 43 and 43 reverse. Published for the first time.

- Quoted from: Russian State Historical Archive, fund 190, file 8, item 846, sheets 42 and 42 reverse, 121 reverse and 122.

- Quoted from: P. Mikhailov’s letter to the Board of Inland Waterways and Highways, March 12, 1912, Russian State Historical Archive, fund 190, file 8, item 847, sheet 197 reverse.

- Quoted from: S. Koluzakov, “A Funerary Memorial for Arkhip Kuindzhi. A. Shchusev’s Project” in The Tretyakov Gallery Magazine, No. 3 (60) (Moscow, 2018), p. 195-213.

- Quoted from: S. Koluzakov, “A. Shchusev’s Kazan Railway. An Unrealized Idea of the ‘World of Art’” [“Kazansky vokzal A.V. Shchuseva. Nevoplosh- chennyy zamysel “Mira iskusstva””] in The Tretyakov Gallery Magazine, No. 2(55), supplement (Moscow, 2017).

- N. Roerich’s letter to A. Shchusev, December 3, 1912. From a private collection. Published for the first time.

- A. Shchusev’s letter to N. Roerich, December 16, 1912, Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery, fund 44, item 1522, sheet 1.

- A. Shchusev’s letter to N. Roerich, April 17, 1913, Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery, fund 44, item 1523, sheet 1.

- A. Shchusev’s letter to N. Roerich, June 3 (1913?), Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery, fund 44, item 1530, sheet 1 reverse.

- A. Shchusev’s letter to N. Roerich, undated (late October - early November 1913?), Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery, fund 44, document 1536., sheet 1.

- N. Roerich’s letter to A. Shchusev, November 5, 1913. From a private collection. Published for the first time.

- Quoted from S. Ernst, “N. Roerich” [N.K. Rerikh] in Roerich’s Kingdom [Derzhava Rerikha], (Moscow, 1994), p. 34.

- For a somewhat different take on the iconography of the chapel’s side walls, see Ye. Matochkin, “N. Roerich: Mosaics, Icons, Murals, Designs of Church Buildings” [“N. Rerikh: mozaiki, ikony, rospisi, proekty tserkvey”], (Samara, 2005), pp. 88-104.

- Quoted from: G. Donskoi, “Renovation of N. Roerich’s Murals in Pskov” [“Restavratsiya monumental'noy zhivopi- si N.K. Rerikha v Pskove”] in N. Roerich's Murals. Study and Renovation [Monumental'naya zhivopis' N.K. Rerikha. Issledovanie i restavratsiya], (Moscow, 1974), pp. 31-47.

Postcard

Private collection. Published for the first time

Lead pencil, Indian ink, coloured ink on paper

Russian State Historical Archive. Published for the first time

Indian ink on tracing cloth. Russian State Historical Archive. Published for the first time

Lead pencil and crayons on paper. 16 × 11.8 cm.

Private collection. Published for the first time

Lead pencil, watercolour, gouache, bronze paint on paper. 34 × 50 cm.

Private collection

Lead pencil, watercolour, bronze paint on paper. 17 × 25.3 cm.

Private collection. Published for the first time

Charcoal, watercolour, bronze paint on tracing paper. 34.3 × 33 cm

Private collection. Published for the first time

Lead pencil, watercolour, bronze paint on tracing paper. 38 × 22.3 cm

Private collection. Published for the first time

Lead pencil on tracing paper. 32.5 × 27.2 cm.

Private collection. Published for the first time

Lead pencil on paper.42 × 66.2 cm.

Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Lead pencil on tracing paper. 36.5 × 27.3 cm

Private collection. Published for the first time

Photo: Alexei Shchusev

Private collection. Published for the first time

Photograph. Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Tempera on cardboard. 47 × 47.5 cm

© Russian Museum

Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Lead pencil, watercolour on paper. 18 × 11 cm. On the margins, a drawing of the old St.Anastasia Chapel and a detail of the metal cover of an unknown icon (from the Paromenskaya Assumption Church?).

Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Private collection. Published for the first time

Pskov affiliate of Spetsproektrestavratsia (renovation company)

Pskov affiliate of Spetsproektrestavratsia (renovation company)

Pskov affiliate of Spetsproektrestavratsia (renovation company)

Pskov affiliate of Spetsproektrestavratsia (renovation company)

Pskov affiliate of Spetsproektrestavratsia (renovation company)

Russian State Historical Archive. Published for the first time

Private collection