Easter Eggs FROM THE IMPERIAL PORCELAIN FACTORY

* General management of the project: Natella Voiskounski. Ivan Golsky, author- compiler, researcher, custodian, The Museum of Ceramics and the 18th Century Kuskovo Estate. Consultants: Tamara Nosovich, Deputy-director, Custodian of the Porcelain Fund of the Peterhof Museum-Reserve; Anna Dobakhova, Expert, P.M. Tretyakov Independent Art Research & Expertise. Images in this publication are from the relevant museum websites.

The illustrated album “The Imperial Porcelain Factory. Easter Eggs. St. Petersburg. Private Collection” was published in Spring 2017 by the GRANY Foundation.* Its appearance marked the conclusion of a major academic project, one of interest for connoisseurs of decorative art and champions of Russia’s heritage alike.

A new album surveys a Russian private collection devoted to the remarkable output of the St. Petersburg ceramics factory.

Project manager: Natella Voiskounski; Author: Ivan Golsky. Moscow, GRANY Foundation, 2017. 426 pp.: illustrated.

The publication marked a significant event in the nation's cultural history - the acquisition, in 2015, by a Russian collector of 227 Easter eggs made by the St. Petersburg Imperial Porcelain Factory, and their subsequent return to Russia. The eggs originated from the collection of the American industrialist, Harold Witbeck; Tamara Kudryavtseva, curator of the Russian porcelain collection at the Hermitage, had earlier catalogued it and published a survey in 2001.

These Easter eggs became an invaluable addition to the existing collection of 71 porcelain Easter eggs that the same collector had previously purchased at sales of Christie's and Sotheby's auction houses. Thus, the new album covered an unmatched collection of 298 Easter eggs of distinct historical and artistic value, as well as commemorative significance. These delicate decorative objects evoke both the foundations of European civilization and Russia's own unique culture, inspired by the Orthodox faith.

Porcelain Easter eggs are a Russian phenomenon, and were produced at the Imperial Porcelain Factory from the moment of its foundation. Dmitry Vinogradov, the chemist who originally developed the formula for Russian porcelain, produced the first satisfactory samples of hard-paste porcelain in 1748. In the third week of March 1749, he wrote in his work journal: “Today we turned and moulded the [Easter] eggs." While initially Russian porcelain production was modelled on the finest examples from the Meissen porcelain factories in Saxony (which were the first porcelain manufacturers in Europe), these miniature works of art celebrating Easter were original creations.

From time immemorial, Easter was celebrated in Russia as the “Feast of Feasts", and marked with profound piety: thus, it is only fitting that the idea of making porcelain Easter eggs as a symbol of renewal and hope would appear in Russia. The precious medium of porcelain, which is sometimes known as “white gold", was indeed filled with symbolic meaning when it lent itself to the Imperial Easter eggs. Regardless of the variety of styles and themes that were used in their decoration, Easter eggs retained their powerful Christian symbolism. For Russians, an Easter egg was not unlike a precious miniature icon made in porcelain, an heirloom that occupied the krasny ugol, or the “holy corner" in the family home.

Easter Egg. Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1860-1870s (?)

Bisque, perforation, relief. Height - 8.2 cm

The custom of giving porcelain Easter eggs as gifts originated at the Imperial court and served to express the inviolability of the brotherly Christian union between the Emperor and his people. The introductory article that opens the new album is illustrated with images of Easter eggs decorated with the monograms of Emperors and Empresses, Grand Dukes and Duchesses. Its first section is dedicated to Easter eggs with religious paintings and scenes from the Gospels, including eggs with miniature copies of icons from St. Isaac's Cathedral (1818-1858) in St. Petersburg and paintings from the Imperial Hermitage. The album continues with a series of Easter eggs decorated with religious paintings based on sketches by Viktor Vasnetsov, Mikhail Nesterov, Osip Chirikov and Alexander Kaminsky, principally for the interior of the Cathedral of St. Vladimir (Volodymyr) in Kiev (1862-1896). Its third chapter covers Easter eggs decorated with landscape paintings and commemorative images, divided into two groups: eggs with paintings based on the “Views of Palestine" series (1842-1843) by the brothers Grigory (1802-1865) and Nikanor (1804-1879) Chernetsov, and those with views of St. Petersburg and its surrounding country estates. The final chapter covers Easter eggs with flower paintings and ornamental compositions.

The publication established new attributions and revised previously accepted information about certain objects of art. However, the format of the illustrated album did not allow for research-style annotations or references to attribution sources. This article therefore offers information on the original sources of paintings and their prototypes, such as lithographs of renowned European religious art and illustrated publications.

The Imperial Porcelain Factory in St. Petersburg was under the aegis of the Cabinet of His Imperial Majesty, which managed the private property of the Romanov family. Like the famous manufacturing enterprises belonging to the royal houses of Western Europe, the St. Petersburg factory was the property of the Crown. The factory was a source of national pride as one of the most important and prestigious manufacturers of objects of decorative art. By special provision, the factory manufactured works of art for the Imperial family, including objects to be used as His Imperial Majesty's gifts to various individuals and organizations, primarily on the occasion of the “Feast of Feasts" - the Holy Resurrection Sunday.

The egg is a long-established symbol of life's renewal. In the Russian Orthodox tradition, the Easter egg symbolizes the tomb of Christ and His resurrection from its depths. This interpretation led to the choice of the egg as the symbolic object that serves to illustrate the meaning of Easter. After the Saviour's ascension into heaven, Holy Equal of the Apostles Mary Magdalene came to Rome to preach the Gospel and greeted the Emperor Tiberius with the words, “Christ Is Risen!" She presented him with a red egg, as the symbol of Jesus Christ's sacrifice to redeem humanity, and of Adam's head, covered with blood that was shed on the Cross. That was when she began preaching to the Emperor and started the tradition of the Easter egg, which began in the years of the 30s of the First Century AD but was formalized only much later, in 1553.

The custom of blessing such dyed eggs in church took shape in 1682 and reached Russia through Poland in the 1720s. Up until the 1850s, eggs were dyed only with a “blood" red colour. Later on, Christians in Bohemia, Poland, Ukraine and Russia began decorating Easter eggs with painted patterns and ornamentation as a way to celebrate Christ's Resurrection and the beauty of God's world.

The Russian Imperial tradition of manufacturing porcelain eggs as presents dates from the reign of Catherine the Great, with such symbolic Easter gifts usually reserved for courtiers and those close to the Romanov family. It was during the reign of Nicholas I that traditional porcelain Easter eggs became true works of art: larger in size than before, they offered a perfect surface for miniature copies of paintings from the Hermitage, works close to the heart of the Emperor and his family. Ceremonial presentations of these unique artworks were held to mark name days, birthdays, marriages, and other important events in the life of the Imperial family. Naturally, the images and motifs that decorated these Easter eggs were carefully chosen, with miniature portraits of saints, copies of paintings, landscapes, floral motifs and ornamental patterns conveying personal messages.

In the 1840s-1860s, the most popular designs included paintings from the Hermitage, the Winter Palace and the royal residences outside St. Petersburg: artists of the Imperial Porcelain Factory were given special access to the art gallery at the Hermitage. The introduction of lithography in Russia in 1816 allowed the public wider access to reproductions of works of art, etchings being the most common source for genre miniatures. To provide samples of original art for their painters to copy, the factory administration regularly purchased illustrated books and publications, as well as watercolours and original sketches by famous artists.

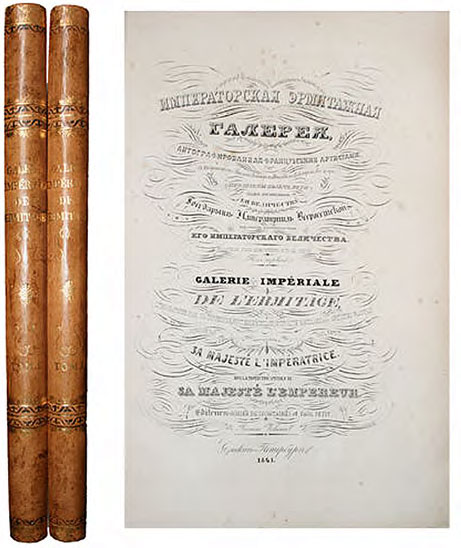

The collection commemorated in the album includes four Easter eggs painted with copies of works from the “Imperial Hermitage Gallery" series of lithographs, dated 1845-1847. Another source was the “Gravures de la Galerie du Palais d'Orleans", a famous volume published in 1786 in Paris which reproduced 500 paintings from the collection of Philippe II, Duke of Orleans. From that publication came the Easter egg images titled “Rest on the Flight into Egypt", and two eggs with similar images of Mary Magdalene, which were created at different times.

In the 1840s-1860s, when the works of the Old Masters and the academic realists alike were at the height of their popularity at the Imperial court and throughout Russian society, miniature copies of the graceful and emotional images of Guido Reni were often used to decorate porcelain Easter eggs.

Reni was both a painter and printmaker, and achieved considerable recognition in his lifetime, but he became truly famous only after his death, when his work was acclaimed on a level comparable to that of Raphael the “Divine". For three decades the work of Italian artists of the Bolognese School set standards equally for masterly painting accomplishment and ideal images. According to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, in the period 1890-1907 the Imperial Hermitage had 11 paintings by Guido Reni. The private collection catalogued in the new album includes nine eggs painted with copies of Re- ni's works (the attribution of one of them was completed only after its publication).

Porcelain Easter eggs allow us to share the stories and the generous touch both of those who created them, gave them as gifts or received them with gratitude, and of those who later collected and treasured them with such love and care. Their miniature paintings are a feast for the eyes, while their messages, whether concealed or clear, delight the mind. It is a field that undeniably rewards further study.

The Holy Family

From “Imperial Hermitage Gallery”. Engraving after “Madonna del Latte (Nursing Madonna with an Angel)” by Antonio da Correggio. Museum number: 1859, 1008. 28. British Museum

Easter Egg “Madonna and Child with an Angel”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1870s

Underglaze cobalt, overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 10.9 cm

Egg with painting after “Nursing Madonna with an Angel” by Antonio da Correggio. 1489-1534. Purchased by Imperial Hermitage (State Hermitage, inv. № ГЭ-87) from I. Kazanova in Dresden, Germany. The work is currently housed in the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest (Inv. № 55)

Madonna and Child

From “Imperial Hermitage Gallery”. Engraving after Andrea del Sarto. Museum number: 1843,0513.700. British Museum

Easter Egg “Madonna and Child”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1870s

Signed by porcelain painter’s initials: A.S. Overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, imitation of diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 11.2 cm

Egg with painting after “Madonna and Child” (1787) by Andrea del Sarto (1486-1530). From the Imperial Hermitage collection

The Allegory of Faith

From “Imperial Hermitage Gallery”. Engraving after Moretto da Brescia Museum number: 1859,1008.50. British Museum

Easter Egg “The Allegory of Faith”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1845-1855

Overglaze laying, overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, imitation of diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 9.1 cm

Egg with painting after “The Allegory of Faith” by Moretto da Brescia (1498-1554). c. 1540. Acquired by the Imperial Hermitage collection (inv. № ГЭ-20). in 1772 from the Paris collection of L.-A. Crozat, Baron de Thiers (1661-1740).

Christ Carrying the Cross

From “Imperial Hermitage Gallery”. Engraving after Lodovico Carracci. Museum number: 1859,1008.35. British Museum

Easter Egg “Christ Carrying the Cross”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1845-1855

Overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, imitation of diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 8.5 cm

Egg with painting after “Christ Carrying the Cross” by Lodovico Carracci (1555-1619). Acquired by the Imperial Hermitage (Inv. № ГЭ-1613) in 1779 from the collection of François Tronschen (1704-1798) in Geneva, Switzerland. The painting is currently attributed to an unknown 17th century artist of the Bolognese School.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt

Engraving after Pier Francesco Mola. 1786-1808. Museum number: 1855,0609.394. British Museum

Easter Egg “Rest of The Holy Family on the Flight into Egypt”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1870s

Overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, imitation of diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 9.1 cm

Egg with painting after the print from “Rest on the Flight into Egypt” (1630-1635) by Pier Francesco Mola (1612-1666). Currently at the National Gallery, London

St. Mary Magdalene

Engraving after Guido Reni. 1786-1808. Museum number: 1855,0609.371. British Museum

Easter Egg “St. Mary Magdalene”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1830-1840s

Signed with painter’s initials: A.P. Overglaze polychrome painting, gilt on paste, diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 8.8 cm

Egg with painting after the print from “St. Mary Magdalene” by Guido Reni (1634-1635). Currently at the National Gallery, London

Easter Egg

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1750-1760s

Overglaze monochrome painting, gilt on porcelain. Height - 6.7 cm

Egg with painting on one side after the print “The Annunciation”. The State Hermitage online digital catalogue lists a 19th century lithograph of an earlier composition “The Annunciation” by the lithographer Legris. Inv.: ОГ-391883

URL: http://е-expo.hermitage.ru/

The Infant Christ with a Floral Wreath

Lithograph from the collection of the Royal Bavarian Picture Gallery, Schleissheim Palace, by Franz Dahmen after Carlo Dolci. 1823. Museum number: 1854,1020.1457. British Museum

Easter Egg "The Infant Christ with a Floral Wreath"

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1862-1870s

Signed with the painter’s initial: P. Overglaze polychrome painting, enamel, gilt, diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 9.0 cm

Egg with painting after the print from a fragment of “The Infant Christ with a Floral Wreath” by Carlo Dolci (1616-1686) (1663). It is possible that the source of this lithograph was the literary and artistic monthly periodical “Art Galleries of Europe. Notable Works from Various European Schools of Painting”, published by Maurycy Wolff (1825-1883) and edited by the renowned art scholar Alexander Andreev (1830-1891) in St. Petersburg in 1862-1864.

Virgin Mary and Child with St. Francis of Paola

Engraving after Francesco Solimena. c. 1757. Museum number: 1855,0609.1315. British Museum. From “Engravings from the Most Famous Pictures of the Old Masters Gallery”, Dresden

Easter Egg “Virgin Mary and Child”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1850-1860s

Signed with porcelain painter’s initials: K.Z. Overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, imitation of diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 11.2 cm

Egg painted with a motif from a copy of “Virgin Mary and Child with St. Francis of Paola” (1703-1705) by Francesco Solimena (1657-1747), currently in the Old Masters Gallery in Dresden, Germany.

Porcelain tablet with image of a Saint (thought to be St. Alexandra)

IPF. 1825-1855. State Hermitage. The Imperial Porcelain Factory Museum. Inv.: Мз-И-674

Easter Egg "The St. Great Martyr Alexandra"

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1860-1870s

Painter Mikhail Kryukov (signed M.K.). Overglaze laying, overglaze polychrome painting, enamel, gilt, diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 10.8 cm

The frame over the painting on the egg erroneously identifies the image as that of St. Olga, but it is the St. Great Martyr Alexandra who is depicted here, holding a palm branch and a sword. A wood panel with a painting of St. Alexandra with all her attributes, exhibited in the permanent collection of the Imperial Porcelain Factory Museum, was instrumental in correcting the error. Alexandra of Rome is a Christian saint revered as a martyr. We know about Alexandra from the life of St. George, where she is identified as an empress, the wife of Emperor Diocletian. Alexandra, who witnessed the suffering of St. George and God's repeated miraculous succour, accepted Christ as her Saviour and openly declared her faith, for which her husband sentenced her to be beheaded.

Porcelain tablet painted with a copy of “Michael the Archangel”

(Inv. title: Tablet with image of St. George). Painter: Alexander Nesterov. IPF. 1844. State Hermitage. The Imperial Porcelain Factory Museum. Inv.: Мз-И-687

Easter Egg with inscription “Michael the Archangel”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1860-1870s

Painter: Alexander Tychagin (A.Т.). Overglaze laying, overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, diverging pattern on porcelain; silk ribbon. Height - 11.0 cm

Painted egg after the work “Archangel Michael Fights Satan” presumably ascribed to Timofei Neff (1805-1876). A porcelain tablet with the complete original painting from the permanent exhibition of the Imperial Porcelain Factory Museum was instrumental in clarifying the origin of the composition.

Fyodor BRYULLOV. Icon. St. Alexei. 1847-1848

(with Slavonic script on the top “St. Alexei, Metropolitan of Moscow and all Russia”). The Museum St. Isaac’s Cathedral, St. Petersburg State Catalogue Number: 4179560

Easter Egg “St. Alexei, Metropolitan of Moscow and All Russia”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1850-1860s

Painted by N. Voronin (signed N.V.). Overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 10.6 cm

Egg with painting after the icon “St. Alexei, Metropolitan of Moscow and all Russia” (1847-1848), by Fyodor Bryullov (1793-1869) crafted for St. Isaac’s Cathedral, St. Petersburg. The inscription “Gregory of Nazianzus” in the frame above the image is mistaken. In 2001 the painting on this Easter Egg was erroneously attributed as a copy of a work by Timofei Neff (1805-1876).

Children's Island in Tsarskoye Selo Park

Engraving from the collection of F.M. Dostoevsky Literary Memorial Museum, St. Petersburg

Easter Egg “View of Children's Island in the Alexander Park at Tsarskoye Selo”

Imperial Porcelain Factory, St. Petersburg. 1870s

Overglaze polychrome painting, gilt, imitation of diverging pattern on porcelain. Height - 8.8 cm

Egg with painting after the lithograph by Karl Kolman (1786-1846) “View of Children's Island in the Alexander Park at Tsarskoye Selo” (1830). During the reign of Nicholas I, an island on the pond at the Tsarskoye Selo park was fitted out for his son and heir Alexander as a place to play and study. In 1830 the architect Alexei Gornostayev (1808-1862) oversaw the building of a small children’s playhouse, designed by the architect Vasily Stasov (1769-1848). In 1830 Karl Merder (1787-1834), the heir’s tutor, suggested that the children think of a motto for the island, which had become their home. The result of their collective creative effort was a drawing of “a cliff, washed clean with water, an ant, and an anchor”, symbolizing “persistence, action, and hope”. Presumably, the ant, as the symbol of the Children’s Island, later lent its name to the handwritten magazine “The Ant”, which the heir, with the help of his friends, started “publishing” in 1831. When the children of Alexander II and his brothers grew old enough, they continued to explore the territories previously “occupied” by their parents. Alexander II passed his love for the Children’s Island to his children and grandchildren. The children of Nicholas I, Alexei and his sisters, the Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria and Anastasia, enjoyed playing here, boating on the pond, planting flowers and shovelling snow in the winter. They were often joined by their father.