Iulian

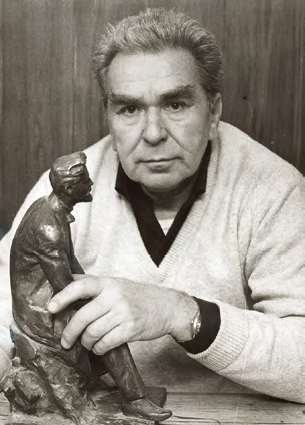

The precious time of childhood. A son remembers his father: Alexander Rukavishnikov recalls Iulian Rukavishnikov.

“I did harm not my loved ones, nor grasses nor weeds,

To the land of my forefathers, I remained true...

Still, the sky rose above me in limitless peace,

Stars would drop from the heavens, and onto my sleeve.”

Arseny Tarkovsky

Iulian was born in Moscow on 30 September 1922. When he died in 2000, I was 50 years old. His death could be said to mark the end of my childhood.

Losing one’s loved ones is never easy, and, if they were anything like Iulian, it is truly devastating. Iulian, indeed, “would harm not his loved ones, nor grasses nor weeds”. At our dacha in Velyaminovo, he would rise at dawn. I was aware of this even as I snoozed: our dog Fromage, who slept by my bed, would always yawn and rise reluctantly, preparing to do his duty by watching over and following his master. Leaving the house, father would go to tend his beloved garden, which was indeed magnificent... The birds, who knew him well, would gather for an early breakfast; he, however, breakfasted with us, some four hours later... Sitting with us at the table, he would prepare sandwiches for himself and for the dog.

Konstantin Korovin wrote of the young Chekhov that the boyish writer was nevertheless like a “kind old granddad”. Iulian produced something of the same impression. His approach to order in his studio was most unusual, very much his own. Using a collection of straps and slats, he contrived to create his own little corner, a kind of den in which all the necessary tools remained close at hand, as if suspended in the air. His real life was of course centred around his work in this den. He was, I feel, a truly great sculptor, born in the wrong place and at the wrong time. His many epigones, his would-be followers past and present, have naively tried to imitate his art, yet they have usually lacked imagination and a sense of measure. Thus, they are doomed to failure. When Iulian worked on his sculptures, he was always developing, transforming, selecting, favouring one detail over another, often introducing elements appropriate in form, yet dissonant in meaning. He was the first to talk to me about the care with which one needs to treat form, and about the poignant trepidation with which one should approach volume. Later, I heard something similar from a wonderful Vietnamese sculptor, Le Cong Thanh. Small and puny-looking in appearance, that man was truly great and powerful in his art. My father would often encourage me to forget all I had learned, and to free myself from the tyranny of all rules and stereotypes. His masterpieces such as “The Flea", “Clusters of Black Grass", “Seagulls" and “The Sandpiper" certainly show how well he himself was able to do this.

Konstantin Korovin wrote of the young Chekhov that the boyish writer was nevertheless like a “kind old granddad”. Iulian produced something of the same impression. His approach to order in his studio was most unusual, very much his own. Using a collection of straps and slats, he contrived to create his own little corner, a kind of den in which all the necessary tools remained close at hand, as if suspended in the air. His real life was of course centred around his work in this den. He was, I feel, a truly great sculptor, born in the wrong place and at the wrong time. His many epigones, his would-be followers past and present, have naively tried to imitate his art, yet they have usually lacked imagination and a sense of measure. Thus, they are doomed to failure. When Iulian worked on his sculptures, he was always developing, transforming, selecting, favouring one detail over another, often introducing elements appropriate in form, yet dissonant in meaning. He was the first to talk to me about the care with which one needs to treat form, and about the poignant trepidation with which one should approach volume. Later, I heard something similar from a wonderful Vietnamese sculptor, Le Cong Thanh. Small and puny-looking in appearance, that man was truly great and powerful in his art. My father would often encourage me to forget all I had learned, and to free myself from the tyranny of all rules and stereotypes. His masterpieces such as “The Flea", “Clusters of Black Grass", “Seagulls" and “The Sandpiper" certainly show how well he himself was able to do this.

When you were with him, it always felt warm and cosy. More than anyone else, he showed me how crucial to one's creative success are the comfort and order that one can nurture around oneself. This may sound somewhat abstract or relative, yet it is clearly important to begin one's work with organizing one's work space. We are talking of simple things: lighting, the height of one's stool, the correct height of the bench. The space should be quiet and clean. Then, and only then, can one hope to get on the right wavelength, find the right connection - however you choose to put it. Those poor fellows, whose teachers fail to tell them this, or to explain it properly - they're just wasting their time. Then too, you often hear those banal statements about “creative disorder". In my view, that's just like practising martial arts without proper breathingor understanding the currents of internal energy: it's just going through the motions.

At the studio with friends (the sculptor Yury Neroda, right). Photograph

Often, he would telephone and say privet, “hi", in that special way of his, lingering on the vowels as if he was smiling. His greeting was always cordial, and at the same time, a little insistent: “I need some advice, why don't you come round." Usually, two or three sculptures would be standing on the small table, the plasticine would be poorly mixed and patchy, but that did not hold him back: he saw only form. Usually he would already have prepared a lot.

Recently, we had a good laugh together, rehearsing behind the scenes at the circus in preparation for my birthday celebration. The wonderful Tatyana Nikolayevna and Maxim Nikulin were so kind as to offer us the Moscow Circus for the occasion. lulian Mitrofanovich and Sergei Sharov were very actively involved. The rows of seats were replaced with tables, while outside guests were greeted by clowns on stilts, camels and horse riders. My father had always dreamed of having his own elephant. I thought he was joking, but he persisted in listing the positive qualities of these animals, compared to all other beasts. As a result, a special routine was devised for me, and I set about rehearsing with a young female elephant (I do not recall her name). We were told that in the past, she had been very wild and impossible to tame, so her previous owner had got rid of her. Taking her on and treating her with kindness, the new animal trainer had helped her to become calmer and more obedient. He taught us how to place lumps of sugar in her maw in order to encourage her. Her big mouth was wet and hot, her eyes always attentive and vigilant, the gaze somewhat unkind. After a while, Iulian sent me off to rehearse other acts, while he remained with the elephant. Returning after some time, I witnessed a most touching scene. The elephant was sitting on her behind, as my father sat facing her on a stool. His cheek resting on his hand, he was smiling at her with rapt Zen-like affection. Beside him lay a pile of neatly folded empty sugar boxes. “So will you make a portrait or figure of her, then?" I enquired. “Of course!" he replied at once. Had he had time to carry out this project, it would doubtless have been quite delightful. .

Angelina and Iulian at the studio. Photograph

I should perhaps say a few words at this point concerning my father's choice of subjects. His compositions were always thought through, right down to the very tiniest detail. For this reason, almost all his works are quite capable of being enlarged, while still retaining their appeal. Most often, we see a very different picture: large-scale works which have not been properly thought out, resulting in chaos or comedy when they are enlarged. Among his works that proved successful in a larger format are “Four Lilies", “Butterfly on a Leaf", “Snails" and “Pupa". The hours he devoted to studying the art of the ancients - Egypt, Indonesia, Greece, Japan and Mexico - paid off well. Among the Europeans, his favourites were Aristide Maillol, Carl Milles and Karl Blossfeldt. Blossfeldt he always considered a particular authority, often repeating: “He's already found everything." I must also add that he made a lot of changes, usually favouring a more laconic solution.

I well recall our battles at home in the late 1970s. I also remember the incredible search for the agricultural expert's raincoat. Without this, he could not start work on the figure of the director of the collective farm for his composition, its figure doubtless inspired by the actor Mikhail Ulyanov, who had played the leader of a kolkhoz in the film “The Chairman". The model had long been found, yet the necessary raincoat continued to elude him... Tired of his stubbornness to continue the searches for the raincoat, mother and I would yell at him, until one day an invitation arrived to take part in some outdoor ecological exhibition at the VDNKh Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy.

Finally, Iulian made a laconic bronze leaf, around 90 centimeters long, not without a lot of fuss from us. Against the backdrop of other works, this sculpture gained notoriety among a particular group of Moscow artists. The following morning, as they say, he awoke a true master. Under the influence of those times, his incredible, mysterious, sacral works began to take shape one after the other, slowly and tortuously at first, then faster, bolder, more freely. In time, his direct connection with the Almighty was firmly established, and things began to flow with power and grace. Mother and I were overjoyed, although we remained his strictest critics, notwithstanding.

“Get rid of those eyes!"

“What do you mean?" he would typically respond.

“Just get rid of them!"

“The bird's leg is too realistic. Turn it into a part of some mechanism".

“A part. Why don't you just get lost!"

Often, in fact, he would listen and agree with us, which at first I found strange. My father's character is entirely different to mine. I tend to seek compromise; my behaviour follows the Eastern mindset. I form no intentions, acting instead according to circumstance. Once, reading a horoscope, I found the following description of my star sign: “Librans are incapable of heroic deeds." That assessment gave me some satisfaction. Iulian, on the other hand, was perfectly capable of heroism. If ever he chose to break off relations with anyone, it was always for good. Most people adored him, though. To this day, I come across people from different walks of life, who say to me: “We knew your father, you know." Their expression appears to add: “You're nothing like him." And I can't help but agree.

They say, with age, one begins to resemble one's parents in appearance. Father's character, however, was one of basalt, whereas mine is mere feather grass.

One year, sometime before his creative rebirth, he was commissioned to create a marble portrait of Brezhnev. By that time, Leonid Ilyich was not in good health, and his face had become somewhat asymmetrical. I gave father some help. We wanted to make the portrait look good, so in the end, we produced a likeness of Iulian himself, as he resembled Brezhnev. The work was five or six times actual size. Our workmen carved the likeness out of marble and polished it; blissfully unaware of any problem, we set off with it, as well as a few other works of mine for the Manege. His colleagues, however, immediately burst out laughing. “You're a character all right, Iulka! Putting yourself up in the Manege at the Party Congress exhibition! In the very entrance hall, too!" “Perhaps you could be a little more careful now, Iulian Mitrofanovich," Pyotr Demichev, Minister of Culture, cautioned my father anxiously. The phrase became something of a mantra among Moscow sculptors, who would cite it long after that fateful event was over.

I do not know why, but everyone in those days appeared to be feverishly jolly: perhaps this was due to the higher standard of living that had finally arrived. Accustomed to this gaiety as a child, later I began to find it irritating. It could have been promoted by certain cinema propaganda, as well. Compared to Soviet people, foreigners, who behaved in a more natural manner, really stood out. The guests who frequently came to our home in large numbers seemed always in paroxysms of laughter. Tossing and turning in my room on my sofa, I could not sleep: such was the carefree Moscow life in the 1960s and 1970s. By the 1990s, people somehow became more ill-tempered. As a child, however, I entered an attractive, mysterious and festive world of kind people, enlightened people, who knew about architecture, art and music.

Its main character, of course, was my lively, gay, occasionally sad, stunningly beautiful mother. Her beauty was not that of a model; she was sometimes uncompromising, and often sarcastic. Everyone called her “Alka" with deliberate familiarity; for me though, she was my beloved mother, who always treated me with such tenderness. My maternal grandmother Lyubov Alexandrovna, and my paternal grandmother Alexandra Nikolayevna were both highly intellectual and most noble. Lyubov, who had trained at La Scala and possessed a coloratura soprano, loved to sing Lyubasha from “The Tsar's Bride", “Tosca" or “La Traviata" around the house. At bedtime, both grandmothers would read to me from Pushkin or Andersen. I still have the beautiful old books of fairy tales published by Knebel with their fabulous illustrations. The entire vast book collection amassed mainly by my grandfather Nikolai Filippov was, indeed, at my disposal: then, just as now, it was housed on the shelf below the ceiling. My grandfather had also decorated the walls with fragments of works by Michelangelo, Titian, Piero della Francesca, Tintoretto, Mantegna and others. On the wide old black shelves, colour fragments of Luca della Robbia and Jacopo della Quercia reproductions were arranged. Over all this presided grandfather. He worked, seated at his huge oak easel, made to order according to his own design. Arranged in some incomprehensible way, all around him in special drawers lay countless kneaded erasers, Italian and French black and grey chalks, maulsticks, sticks of sanguine and the long brushes made, I think, by Rembrandt. He also compiled immensely thick albums with examples of the best-known world art, focusing on particular aspects such as “The Colour White in Dutch Painting", or “Craquelure"... I use them to this day.

The superhero in this set-up was of course my handsome, dark-haired young father. Strong and bold, he was always kind to me. In their televised revelations, many of today's romantic storytellers like to reminisce about having been real tearaways in their youth, leaders of Arbat gangs even. I, on the other hand, was more of a mummy's boy. My presence among my rough, streetwise peers appeared to arouse them as a red rag would a bull. This placid, plump son, who put one in mind of a good-natured old horse, was clearly out of place with his energetic, warrior-like father, who had grown up in the outer reaches of Krasnaya Presnya. Father bought boxing gloves, punch mitts and a punch bag, and began to train with me. It didn't work though, and nothing helped, until finally I found myself at the Trud boxing club on Tsvetnoi Boulevard, under the auspices of the legendary Lev Sigalovich. This wonderful, kindly old man, who greatly resembled the actor Louis de Funes, was the life and soul of Moscow's entire boxing scene. His grave in Moscow's Vagankov Cemetery lies next to that of my father, Iulian. A coincidence? I do not know. We know only that we know nothing.

Around 1966, my father won a competition to create a statue of Chekhov in Taganrog. Back then, evidently, one could still take part in such competitions. Our family entered a dark age of gathering the necessary materials, everyone in a state of constant stress. This was probably the first time that he took me to the sculpture kombinat with him: I was to help in creating the big statue. It was a whole new world, with foundry workers, handymen, enlargers and waterers, whose worldview appeared reminiscent of characters from Bunin's “Dry Valley" and “The Village". My new setting made a profound impact on me. Gradually, I grew more accustomed to it, and began to enjoy living at the plant. We took our meals together, and the others would drink a little - not me, though, I was concerned about my fitness. One time, I tripped on a piece of board and fell off a scaffold. Flying past the level where father was working, I saw him turn his head and look at me - somewhat condescendingly, I felt - shaking his head in silence. I was not hurt by my fall - I was young. Later, recalling that incident, I decided that my father's response had perhaps been the most powerful lesson he could have offered in the circumstances. Maintaining complete outward calm, he had simply continued with his work. Afterwards, I had noticed that when he was working, he would always finish one detail before moving on to the next. No “creative ecstasy" for him, no frantic to-ing and fro-ing around his sculpture. This did not necessarily imply that the detail was entirely successful and complete; merely, that the work was constantly advancing, that each detail led to the next.

Father worked with many architects, most often, perhaps, with Nikolai Milovidov. Always elegantly turned out, favouring late 19th century fashion, always the exceptionally well-mannered and erudite gentleman. When the two got together, they smoked so much, you could no longer make out their mock-ups, or their sketches. They swore freely, too: such swearing I never heard in my life, before or after, the choice words rebounding everywhere in a constant stream.

Water Clock. 1990

Bronze, aluminium, glass. 50 × 68 × 24 cm

Perhaps the most important factors in enabling his creative life were, for my father, order in his studio and comfort at his home. This was largely due to the war: during a training flight, he had sustained a concussion; he had also suffered through the years of hunger. Hunger, he told me, was a humiliating business. He was something of a pedant, liking to work on his cast bronze pieces by hand and refusing out of principle to use electrical instruments. As for me, he always called me “Sashka, that big lazybones".

The era of Pobeda cowboy cars and sculptors in shirts with abstract na'i'f designs and baggy gabardine trousers with high waistlines, was over. Gradually, these unique times would fade into oblivion, with their interminable arts council and exhibition committee meetings that invariably ended with a feast in the restaurants of the Metropol Hotel or the Union of Architects. People were beginning to forget about the exhibitions that had, in their time, created such a stir: the American National Exhibition in Sokolniki, Antoine Bourdelle and Sergei Konenkov at the Moscow Artists' Union on Kuznetsky Most, Picasso and Renato Guttuso at the Pushkin Museum, if I recall correctly. The actors of the Bolshoi and Maly Theatres were disappearing, too. Nikolai Gritsenko and Ira Bunina, who lodged with us for a long time and liked to make amusing little quips, which only those from our circle, seated right at the front thanks to our connections, could understand. Slava Rostropovich with the cello that he liked to call his balalaika when among friends; occasionally, his muse would appear, too. Mikhail Astangov, who loved to scare me when I was a little boy of about five. They were many, too many to name here. Someday, perhaps, I will write a book about them. Such, my dear reader, somewhat muddled, perhaps, is the story of my father, that great artist and truly exceptional man, lulian Rukavishnikov.

Bronze. 68 × 110 × 70 cm

Bronze. 100 × 65 × 68 cm

Bronze. 102 × 55 × 52 cm. Presented by the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin to the cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova on the occasion of her 80th birthday in 2017

Marble. 40 × 50 × 12 cm

Ceramics. 50 × 35 × 34 cm

Bronze. 165 × 64 × 55 cm

Bronze. 110 × 60 × 48 cm

Bronze. 87 × 47 × 27 cm

Bronze, stainless steel. 70 × 40 × 25 cm

Bronze. 87 × 45 × 48 cm

102 × 65 × 60 cm

98 × 120 × 48 cm

Bronze. 48 × 56 × 20 cm

Bronze. 58 × 28 × 37 cm

Bronze. 60 × 25 × 20 cm

Bronze. 81 × 42 × 31 cm

Bronze. 130 × 80 × 30 cm

Bronze, marble. 78 × 35 × 16 cm

Bronze. 70 × 56 × 30 cm