George Costakis: The Keeper of Modernities

"GEORGE COSTAKIS. 'DEPARTURE FROM THE USSR...' ON THE CENTENARY OF THE COLLECTOR'S BIRTH" IS THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY'S MAIN EXHIBITION PROJECT OF 2014. BACK IN JULY 2013 THE GALLERY'S KRYMSKY VAL BUILDING OPENED A SEPARATE HALL DEDICATED TO COSTAKIS (1913-1990), STIMULATING THE PUBLIC'S ATTENTION AND INTEREST IN THIS FAMOUS MOSCOW COLLECTOR AND RELENTLESS ENTHUSIAST OF ART. THE EXPANDED SHOW OF WORKS FROM COSTAKIS'S COLLECTION THAT HAS FOLLOWED ALMOST A YEAR LATER HAS BECOME THE TRUE CULMINATION OF THIS UNUSUAL ANNIVERSARY "MARATHON".

The fact that Costakis's accomplishments, previously largely forgotten, are now widely celebrated is explained by one significant circumstance: in 1977 he donated part of his collection (notably, the best and most valuable works of art that he came to own during many years of collecting) to the Soviet state. The events of those years changed his life and made it into a shining example of good citizenship: this is probably the reason why Costakis's efforts are often compared to those of other major Russian art collectors such as Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, and even the brothers Pavel and Sergei Tretyakov, renowned for their generous donations of art to the city of Moscow.

Such a verdict is not entirely fair, however, and hardly true to life. Before the 1917 Revolution everyone, aristocrats, industrialists and merchants alike, were free to both make their purchases openly, and publicly bequeath their property; philanthropy and patronage of the arts were widespread and encouraged. For George (Georgy) Costakis, the process was much harder. He lived in a very different, Soviet era, when any kind of collecting was equated with hoarding wealth, considered unethical and even marginalized as an expression of "bourgeois throwbacks". Costakis's "ideologically alien" passion for collecting icons and Russian art of the i9ios-i93os, the so-called "Russian Avant-Garde", could even be prosecuted as crime against the state. God only knows how Costakis was able to avoid the many pitfalls of hunting for such "forgotten masterpieces", and he did end up saving a huge number of priceless works of art. Costakis put his "forbidden" collection together under such trying circumstances that both his will and his desire to donate part of it to the state, making it accessible to the general public, reflected a private individual's courageous and impertinent challenge to the entire system of acceptable rules of behaviour at this time of"collective thought". In the 20th century, this was an unprecedented case.

It would not be possible to bring together all the works of art that Costakis selected in his lifetime. Like any other private collection, it often went through transformations, first at the decision of its owner, and later of his heirs. It would be futile to attempt to "reconstruct" the already world-famous collection of Russian avant-garde of 1910-1930 as it was in 1977, when it underwent the epic split into two parts, one donated to the Soviet state, the other taken by Costakis with him when he left the USSR. Since then, both parts of the collection have been exhibited in various galleries and museums worldwide, both together and separately, on many occasions. Masterpieces from the two locations - Moscow and Thessaloniki, where they now have permanent domicile as "legal residents" - were often shown together, though never previously in the halls of Russian museums.

The curators of this anniversary show offer viewers a new way of looking at Costakis's collection: instead of focusing on the avant-garde theme, they have used carefully designed tools to shift the viewer's attention to the collector and the magnitude of his personality, to his vast, extraordinary talent as a landmark phenomenon in its historical context. The exhibition showcases different dimensions of the Costakis collection, diverse as it is/ was in terms of the types of artwork amassed, amazing in terms of their artistic quality, and unique as a tangible "encyclopaedia of Russian avant-garde"; magnificently generous, Costakis's donation was an extraordinary landmark event in Soviet history. Along with Costakis and his family we all received the missive: "Departure from the USSR..." is now allowed. This anniversary show and its subtitle, "Departure from the USSR...", is a metaphorical message for the contemporary viewer.

In the Soviet Union in the 1970s every innovative trend in the arts of the 1910s to the 1970s - exactly the kind of art that George Costakis collected - was strictly banned for reasons of ideology. The work of such acclaimed masters as Chagall, Kandinsky, Filonov, Tatlin, Popova and Kliun were not exhibited in Soviet museums until 1986; it was also forbidden to mention the names of many other renowned artists in official publications. The decision whether to accept Costakis's gift became mired for quite a period of time in the depths of the USSR Ministry of Culture, as it was discussed among the highest echelons of various departments. There was no ready answer to such an audacious offer; the bureaucrats had to be creative and make sure the comma in the famous phrase "allow not forbid" ended up in the right place.

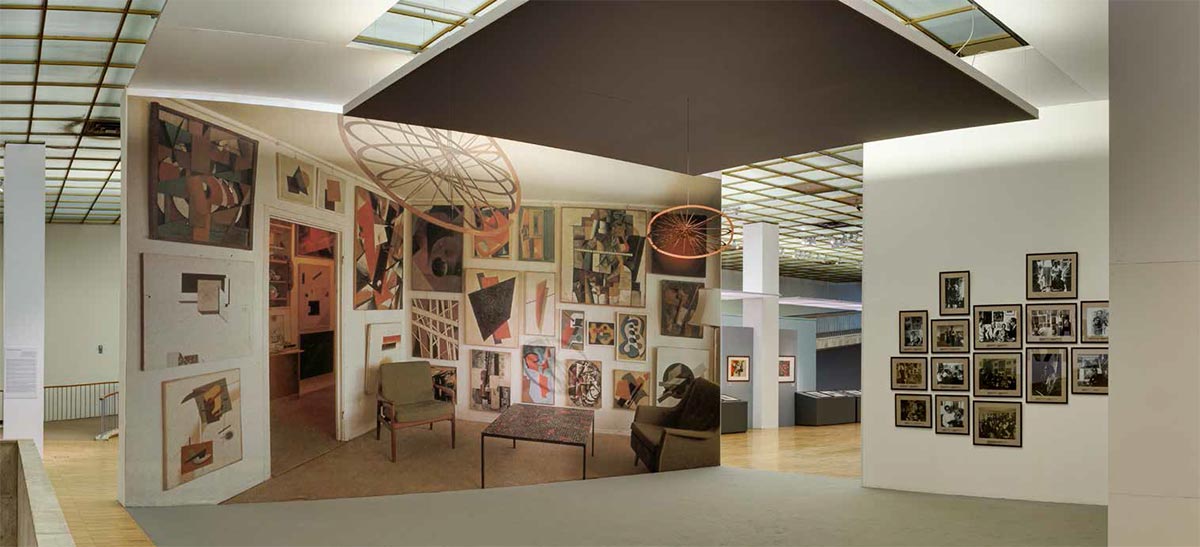

The historical reality of the ethos of the Soviet state, its atmosphere of constant ideological and spatial constraint influenced all artistic and cultural expressions, both the public conscience and the private lives of individuals. Consequently, the post-war era and cultural life in the time of "the thaw" and the years of stagnation are all subjects of the current exhibition. A unique illuminated "cube house" provides a spatial metaphor, an artistic image of that historical period in the space of the show. This symbolic "Costakis house" lends itself to two enormous enlarged photographs of the collector's old Moscow apartment; small and with low ceilings, the apartment had three rows of paintings displayed on its walls. Small black and white photographs in black frames hang close to one another, just as they would in somebody's home, on another wall; they are "silent witnesses", evidence of the conversations that took place at the Costakis residence under Kandinsky's "Red Square".

Many people were interested in seeing Costakis's collection, foreign diplomats and prominent members of the Russian and foreign artistic elites among them. The apartment on Vernadsky Prospect welcomed Igor Stravinsky, Svyatoslav Richter, Marc Chagall, Edward Kennedy, Andrzej Wajda, Michelangelo Antonioni, David Rockefeller, Sergei Kapitsa, Andrei Voznesensky and many others. On the exterior walls of the cube the visitor sees remarkable photographs taken by the well-known photographer Igor Palmin in the 1970s. They show a tight group of non-conformist artists looking straight into the camera; Costakis is always in the centre - their friend, supporter, connoisseur and courageous defender at the infamous "Bulldozer exhibition" that only lasted for half an hour before the authorities had it dispersed. Such was the beginning of that story. The main space of the exhibition is divided into sections in proportion to their importance in Costakis's collection.

Everyone in the Costakis family cherished his collection of icons and liturgical needlework textiles; for these objects, a special "icon corner", reminiscent of the worship corner space in the Orthodox Christian home where icons are placed, was created in the exhibition hall. Fifteen of the 60 works of religious art that George Costakis donated to the Andrei Rublev Museum are shown here. They represent various schools of icon-painting: the "St. George and the Dragon" icon painted in the Novgorod region at the beginning of the 16th century; the double-sided icon "Epiphany - Procession of the Cross", painted in the second half of the 17th century in the tradition of the Russian North; and "Crucifixion of Jesus" (c. 1600), a cross placed over the iconostasis, an especially remarkable example of Serbian religious art, rarely found in Russia. All the ancient icons of the 16th-18th centuries that Costakis donated are regularly exhibited, in different places and combinations, while the unique fragments of monumental frescoes from the Saviour Church on Nereditsa (12th century) never leave their permanent location at the Andrei Rublev Museum.

The well-designed display cases on the opposite side of the exhibition hall allow visitors to examine the smallest objects, from the Tsaritsyno Museum-Reserve, to be seen at the exhibition. George Costakis was fortunate to obtain an unusually comprehensive collection of folk toys made of clay, wood and even straw; by acquiring it from his fellow long-time collector (N.I. Tsereteli, an actor and historian, the author of one of the first publications on folk-toy manufacturing centres), Costakis saved it from being dispersed. This collection was among the rarities donated to the state. The folk art of making children's toys from clay is represented by unique works of the renowned master Larion Zotkin from the village of Abashevo, including his "Goat with Silver Horns" (1919), old Dymkovo "ladies" and "roosters". The sculptural composition "Musicians" was made out of wood in the 1920s in Sergiev Posad; the figure of "Nicholas II on the Throne" was carved at the beginning of the 20th century in the Nizhny Novgorod region. The "Ruby Bolete Mushroom" is one of the rarest representational folk toys that represent the tradition of the Russian North; quite fragile-looking, it was assembled from the various materials that seem to have been available - wood, moss, hemp, birch bark, cord and paper - and combines elements of carving, weaving, assemblage and painting. Costakis donated more than 200 works of folk and decorative art; they were housed in the depository of the USSR Ministry of Culture, waiting for a dedicated museum to be opened, and it was only in 1993 that they found their new "home" in the Tsaritsyno Museum-Reserve.

Most of the exhibition's space is dedicated to the signature part of Costakis's collection, as well as his gift to the Soviet state - the works of the Russian avant-garde that are now on permanent display at the Tretyakov Gallery. The curators have grouped all these paintings and drawings into separate sections, such as early avant-garde, Cubism, Cubo-Futurism, plastic painting, from Suprematism to Constructivism, experimental art trends of the 1920s, the new figurativeness of the 1930s, and late avant-garde of the 1940s. This division reflects the collector's wish and his ultimate goal to create a visual "encyclopaedia of the Russian avant-garde", to show the entire history of this movement in Russian art, a movement that brought Russia's artistic agenda of the 1910s to the forefront of the pre-war European quest for new expression in visual arts.

The exhibition shows works of art from the massive collection Costakis donated to the three Moscow museums, along with a few pieces lent by the collector's daughters. These include Anatoly Zverev's watercolour portraits of members of the Costakis family, several pieces by "non-conformist" artists of the 1950s-1970s, as well as seven canvases by George Costakis himself, accomplished after 1978. These two sections are placed on the gallery in the main room. A similarly-titled album and a companion multi-media project, which include many pieces and archival materials from this collection that have for many years been housed in Greece, Costakis's ancestral homeland, enhance the exhibition. For the first time information on the Greek part of the collection is available to Russian-speaking viewers: George Costakis's path to recognition, both in terms of his contribution to Russian and European culture, and the documented outline of his life, compiled by Lyubov Pchelkina, provides a striking confirmation of that.

George Costakis, a Greek national, was born in Moscow on July 5 1913 and lived in Russia most of his life. His father Dionysius (1868-1932) was from the island of Zakynthos, Greece; he went into the family trade as a tobacco merchant, and at the beginning of the 1900s began doing business in Russia. Dionysius and his wife Elena (nee Papachristodoulou, 1880-1975) had a large and close-knit family, lived well and maintained close ties to the Greek diaspora. George's mother knew several languages, was devout and had a special gift of treating everyone with exceptional thoughtfulness. There were five children in the family: daughter Maris (1901-1970) and four sons, Spyridon (19031930), Nikolai (1908-1989), George (1913-1990) and Dmitry (19182008). After the revolution of 1917, when the family lost all their sources of income, the children began helping their parents by selling small items from their remaining possessions at a local market. With time, the sons, who were taught to understand cars early in life, started working as drivers. The family moved to the settlement at the Bakovka railway station; supported by the men, George's grandmother, mother, aunt and sister with her children would go on living there for the rest of their lives. The household in Bakovka was to be the source of both the collector's dearest memories and worries. In the mid-1920s, the head of this household, as a Greek national, succeeded in getting a job at the Greek embassy; his older sons followed suit, and thus it became a family "tradition". Having finished seven years of grammar school, in 1930 George Costakis was also employed by the embassy as a driver.

Soon after that, the family was shaken by loss: the deaths of their beloved son Spyridon, a passionate motorcyclist, during a race (Vasily Stalin was also racing that day), and then of their father, whose heart could not bear the grief. However, fate did smile upon George at this trying time - in 1932 he met, and a few days later married Zinaida Panfilova (1912-1992). They would have four children: the daughters Inna (b. 1933), Alika (b. 1939), and Natasha (b. 1949) and a son, Sasha (1953-2003). Zinaida came from a family of Moscow merchants, and was thus a member of a "hostile class", so she was not able to get an education that would match her rare beauty and delightful musical voice. Both spouses loved music, so when the hospitable couple had guests, Zinaida sang romantic songs, with "dear George" playing the accompaniment, their "trademark" entertainment.

In 1938 George's mother, aunt and younger brother were arrested. The family was able to get the women out after a few months, but Dmitry ended up spending several years in the Kotlas labour camp. At risk of being arrested, George managed to travel there and visit his brother, and upon his return continued his efforts to rescue him with the embassy's assistance. When the Greek embassy in Moscow closed in 1939, Costakis, due to his family circumstances, did not make use of the opportunity to move to Canada afforded to him. It was difficult for a foreigner to find a job and he accepted a temporary position as a caretaker at either the Finnish or the Swedish embassy. In 1944 he had a stroke of luck when he found employment with the Canadian embassy as a superintendent. Diligent and courteous, sharp and enterprising, he was soon promoted to the position of senior administrator in charge of the Russian staff and granted, together with diplomatic immunity, a privilege that the embassy's Soviet employees did not enjoy - his salary was paid in foreign currency, and he was entitled to exchange some of the money for rubles in a bank. Such were the terms of the employment contract concluded with him as a foreign national.

On the occasions when he took diplomats to antique shops, he could afford modest purchases. Gradually he took to collecting, trying to learn as much as possible about the objects he acquired. He remembered a childhood embarrassment: immediately after the Revolution his uncle Christopher had bequeathed to him a collection of postage stamps, and the boy, unaware of its true value and without asking permission from the adults, exchanged it for a bicycle. The awfulness of what he had done dawned on him later, when rich buyers came for the collection. The family's indignation was hard to bear, and George even decided to flee, but was found at a railway station and taken back to the family house. He remembered that lesson well and always took care to learn what he could about the rarities that came into his possession. At the beginning, he collected old Dutch paintings, porcelain, Russian silver, carpets and textiles. After the war the collector's interests changed cardinally, and so did his collection.

George Costakis described in his memoirs how, in 1946, practically by chance he saw several works of avant-garde artists - in particular, Olga Rozanova's "Green Band" (1917). Born in the old town of Vladimir, Rozanova belonged to a small group of innovative artists. Malevich's Suprematism at that time pioneered for them the notion of "weightlessness", the soaring flight of bodies in space, because the invention of cinema caused "fatigue" when contemplating the static state of the classical formulas. Through the "Green Band" Costakis discovered for himself, much earlier than others did, the world of this new art. He became "infected" with the avant-garde - considering the political situation, collecting this type of artwork was a fairly risky and, in the opinion of many, useless affair. He did not understand anything about abstract art, but the new world of bright colours, previously unknown to him, and simple forms excited his imagination, aroused his curiosity and inspired him to search for a "new art".

His first mentor was his neighbour in Bakovka village, the well-educated archivist, connoisseur of libraries and dynastic collector Igor Kachurin. He advised Costakis on his first acquisitions, suggested how to seek out experts and even gave him some gifts. Costakis did indeed find experts and listened to them, eagerly absorbing the knowledge they shared. He met with Nikolai Khardzhiev, the well-known scholar of Vladimir Mayakovksy, who introduced him to the St. Petersburg avant-garde, the legacy of Kazimir Malevich, Mikhail Matyushin, Pavel Filonov, and the Ender family of artists. He also learned a great deal from Dmitry Sarabyanov, who would later become a leading specialist in the avant-garde and the art of Lyubov Popova. Costakis was assisted in his search by two young art scholars, Vasily Rakitin and Savely Yamshchikov, who were fascinated with his personality and enthusiasm; assistance also came from other artists, who shared with him information about interesting meetings and finds.

Costakis would visit, inspect, choose and, raising the necessary sum, buy the object; then he would clean it, arrange its restoration, put it into a frame and, finally, hang the work on the wall. He was eager to demonstrate to the entire world the exceptional talent of many Russian pioneering artists of the early 20th century, and put all his efforts into this endeavour. Certainly, he hoped that he was the discoverer of this "Klondike" of the Russian avant-garde and that over time, somewhere in the future, the money that his family had been deprived of would be recouped, and his children would understand why they had to endure all this fear and the permanent presence of KGB "watchers" in their apartment block. The collector's profound belief that the art that enraptured and fascinated him so much would be understood and appreciated in the future helped him to preserve the Russian avant-garde artists' priceless works that are today known all over the world. That would indeed be what happened.

In 1955 Costakis became acquainted with Robert Falk, who told him about the story of the arts in Moscow and Paris in the period from the 1910s to the 1930s. Soon Costakis left the USSR for the first time and, immediately after a medical examination in Sweden, hurried to Paris to meet with Goncharova and Larionov, Nina Kandinsky and even Marc Chagall. Goncharova, witnessing the unusual Soviet man's great enthusiasm for the distant past when she and Larionov had been young, painted a small picture in rayonist style and presented it as a token of respect for Costakis's interest. Inspired, he returned home and exchanged several letters with the Parisian artists. Then followed the festival exhibitions in 1956, acquaintance with more interesting people, and the visit to Moscow of the famous critic Alfred H. Barr Jr., founder of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Barr looked over the objects and explained his understanding of the artwork he saw.

© Photo: Artemiy Furman (FURMAN360), 2015

Costakis and Barr disagreed over a number of things, but Costakis was eager to learn the famous expert's opinion, and they began corresponding from time to time. In 1959 Costakis brought early Chagalls from his collection to the artist's show in Hamburg. Things were humming around Costakis: in the early 1960s he visited the experimental artists of the 19204930s Ivan Kudryashov and Alexei Babichev and bought the works of contemporary unofficial artists, first of all Anatoly Zverev, Vladimir Veysberg, Dmitry Krasnopevtsev, Oscar Rabin and Igor Vulokh. His hospitable home was the place where the entire generation of the 1960s was first introduced to the Russian avant-garde, which had a strong impact on the direction of its creative explorations. As new items were added to the collection, Costakis's knowledge and influence grew. In 1973 he delivered a series of lectures in universities in America and Canada, and at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. In the same year, 1973, a show of items from Costakis's collection was held in London.

However, by the mid-1970s Costakis's relationship with the Soviet authorities was increasingly deteriorating and he decided to leave the USSR. Costakis wrote in his memoir that the decision to leave Moscow, where he was born and where he spent most of his life, was not an easy one, taken on account of his health and the air of anxiety which settled around him after a strange fire in his house in Bakovka village, which destroyed many works of the non-conformist artists of the 1960s. The collection that he had put together over many years was an obstruction - it would be difficult to take it out of the country in its entirety. According to Soviet law, only artwork created during the last 40 years could be taken out of the country, after substantial customs duty had been paid. Undoubtedly, as a foreign national, Costakis could have availed himself of different diplomatic channels, but how could he then secure an exit visa for his wife, who was a Soviet citizen, and for his adult children? After consultation with an old friend Vladimir Semenov - a well-known Soviet diplomat and collector - Costakis found a solution. He decided to act and wrote a letter to the Soviet minister of culture Pyotr Demichev on October 26 1976. For nearly 36 years not a single expert had been granted an opportunity to see the letter, but the Tretyakov curators were allowed unprecedented access and, relying on it and other recently declassified documents, put together the whole story of the transfer of the Costakis collection to the Soviet state.

© Photo: Artemiy Furman (FURMAN360), 2015

"Presently I wish to gift to the state the result of my efforts of many years - a unique collection of Russian and Soviet art of the 20th century. The works that I pass to the state include pieces of great aesthetic and material value, very important for the development of the era's culture, such as: Kazimir Malevich's 'Portrait of Mikhail Matyushin', Wassily Kandinsky's 'Red Square', Tatlin's relief, El Lissitzky's 'Proun', Alexej von Jawlensky's landscape, Lyubov Popova's relief and paintings, pictures of Marc Chagall, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Alexander Drevin, Alexandra Ekster, Georgy Yakulov, Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Alexander Rodchenko, Pavel Filonov, Olga Rozanova, Ivan Kliun ('Landscape Racing By'), Jean Pougny... several pieces of propaganda artwork created after the Revolution by Lyubov Popova, Ivan Kudryashov, Gustav Klutsis... pictures of Alexander Volkov, Solomon Nikritin, Mikhail Plaksin, Kliment Redko. Serge Poliakoffs paintings".

The description of the collection was followed by stipulations as to its further existence in the state museums, the key points being as follows: all works were to be passed to the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow; Yakulov's "Landscape with an Amphitheatre" was to be sent to the National Gallery of Armenia in Yerevan; an appropriate portion of the collection was to be on permanent display within the Soviet art section, with an indication that it was Costakis's gift. This provision applied to the display of the works at any show, including those abroad. It was prohibited to separate individual items from the collection, to pass them to other museums and institutions, to sell or gift them. "Passing the largest part of the collection to the state, I ask for permission to take a part thereof out of the country with me... please find attached two separate lists. I believe that in order to settle all matters related to the collection's future, the following individuals should be appointed as trustees: V.I. Popov, A.G. Khalturin, V.S. Manin, V.S. Semenov, V.I. Rakitin, D.V. Sarabyanov, N.G. Costakis..." The Soviet minister of culture was not in a position to independently accept or decline the stipulations set out by the collector, and in early January 1977 he sent an enquiry to the department of culture of the Communist Party's Central Committee.

© Photo: Artemiy Furman (FURMAN360), 2015

This correspondence between the Soviet Ministry of Culture and the Party body responsible for ideology remained classified for many years, and contained the explanation why nearly all of Costakis's terms were accepted: "It can be safely assumed that the acceptance of Costakis's gift and his departure with a portion of his collection will show us in a favourable light politically." Ultimately, in response to the minister's enquiry set forth in the memo signed February 25 1977 by the chiefs of three departments of the Soviet Communist Party's Central Committee, a resolution was drafted and the enquiry reviewed at a meeting of the Secretariat of the Communist Party's Central Committee on March 1 1977. In the resolution of the Secretariat, which was unanimously approved by its six members, the donor's main condition was upheld: his gift was accepted, Costakis himself granted "permission to leave the country and then to return, and live permanently in the USSR, and to own the cooperative apartment - the property of his wife, a Soviet citizen". Permission to take a portion of the Costakis collection to another country was granted as an exception to the law then in force. The reproduction rights for objects from the Costakis collections, in conformity with Soviet legislation, were transferred to the state.

Costakis endured almost five months of uncertain waiting, until on March 16 1977 the Soviet deputy minister of culture Vladimir Popov sent the collector a letter of reply stating that all his conditions were accepted and expressing gratitude: "The Minister of Culture of the USSR expresses its heartfelt gratitude in response to your noble deed." The Soviet Ministry of Culture's Order No. 175, issued on March 14 1977, to set up a commission and receive the items for permanent retention at the Tretyakov Gallery officially drew the curtain over the whole matter. The members of the commission and Tretyakov Gallery staff spent several weeks processing the artwork - it proved the beginning of a new life for the Costakis collection.

In autumn 1977, allowed to leave the country (and also to return there as a permanent residents, something unheard of in the case of people leaving the USSR as emigres), his daughter Alika and son Alexander departed with their families, taking with them a large portion of the collection. Several days after their arrival in the Federal Republic of Germany, the country's

first exhibition of Avant-Garde from the Costakis collection opened at the Kunsthalle, Dusseldorf, where it caused a real sensation.

In January 1978 George and his wife left the USSR, followed by the family of his daughter Inna. In order to support his large family, in autumn 1979 Costakis auctioned off at Sotheby's works by Anatoly Arapov, Alexander Archipenko, David Burliuk, Natalia Goncharova, Wassily Kandinsky, Ivan Kliun, El Lissitzky, Lyubov Popova and many others. A little later, at the very end of 1979, the "Paris-Moscow" exhibition opened - it was the first time that some of the avant-garde pieces from the Costakis collection were displayed abroad, but the organizers for some reason"forgot to mention" the donor's name. Such lack of attention is always unpleasant, and in this case it proved especially hurtful.

Costakis would restore his peace of mind by painting pictures - he took to painting after leaving Russia, when his artwork was no longer hanging around him in his home but was "stored" in museums and bank safes. A grandiose exhibition tour in 1981 and 1982 visited eight American cities, accompanied by the publication of a catalogue of the avant-garde collection and a series of lectures, and followed by displays of the artwork in many European museums. In 1986 Costakis came one more time to the USSR for an exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery, which for the first time printed in its catalogue ten pictures from his collection and a token five lines about him as a collector, along with information about other donors.

Symbolically, George Costakis, who died on March 9 1990 was buried in a cemetery in Athens not far from the tomb of the great Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of the ruins of Troy. At the end of his life Costakis understood that donating a part of his treasure, his discovered"Troy" of the Russian avant-garde, to the people with whom he had shared the trials and tribulations of revolution, persecution, war and ruin, was the pivotal action of his life. Thank you, Costakis!

* Works donated to the Tretyakov Gallery by George costakis in 1977.