“An Unforgettable Friend and a Comrade-in-Art”. PARISIAN ENCOUNTERS WITH ROBERT FALK

The memoirs of the artist Tatiana Mikhailovna Verkhovskaya (known as Tatiana Hirshfeld in 1895-1980 due to marriage) are now being published for the first time. Like Robert Falk, she graduated from the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, having studied under Konstantin Korovin. In 1939, she joined the Artists’ Union of the USSR and later became famous, largely for her work on theatrical sets and costumes for many venues, including the private Korsh Theatre, the Moscow Satire Theatre, the Moscow Operetta, and the Bolshoi Theatre.

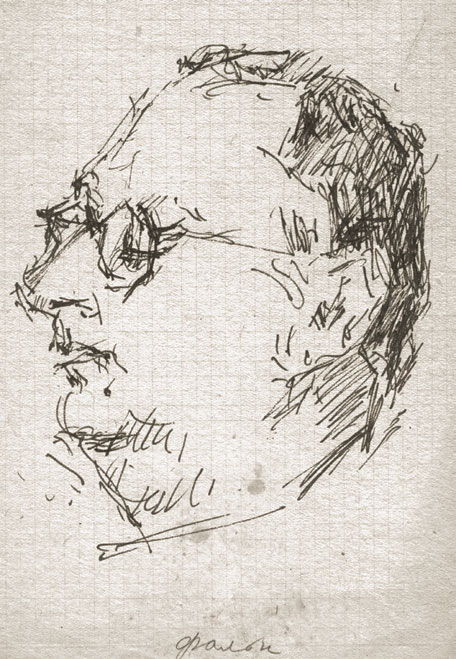

ANDREI YUMASHEV. Portrait of Robert Falk. 1950

Ink, pen on paper. 18.7 × 13.8 cm. © Yaroslavl Art Museum. First publication

Tatiana Verkhovskaya and Robert Falk met in Paris; she lived there in 1934-1938 with her husband Yevgeny Hirshfeld,[1] a diplomat and second secretary of the Soviet embassy in France. Her story refers to events that occurred in 1934-1937, a period of three years out of the nearly full decade that Falk lived in Paris. According to her account, it was Verkhovskaya who introduced Falk to Andrei Yumashev, the pilot who would become the artist’s backer during the difficult period following Paris, at a reception at the Soviet embassy in 1936.

The memoirist describes numerous instances of creative collaboration with the master, including nude studies and landscapes on the streets of Paris and in the surrounding environs. The account of the memoirist’s collaboration with Falk on the Soviet Pavilion at the International Exposition in Paris in 1937 is especially valuable. Until recently, this episode of the artist’s biography was practically overlooked in the literature. Verkhovskaya’s description of how Falk participated in that historically significant project reveals interesting details about the artist’s innovative work on the displays for the section of the exhibition dedicated to painting, theater, and light industry. It is now known that Falk became involved in this work on the advice of the memoirist herself, whose husband was the commissar of the Soviet pavilion (his signature is on the certificate granted to Falk as a participant in the exhibition, which has been preserved at the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art).

Special note must be made of the descriptions of Falk’s work on pieces related to places Lenin had visited during his emigree period: “House in Longjumeau, where Vladimir Lenin stayed in 1911” (mid-1930s, paper, gouache, State Historical Museum, Moscow), “Cafe in Paris that Lenin visited,” etc. There is no doubt that working with the maftre influenced Verkhovskaya’s own work. The composition of the self-portrait she painted in 1939 is quite close to Falk’s pencil portrait of the artist, which was preserved by her family and is now on display here for the first time.

Although Verkhovskaya sometimes took Falk’s advice rather gruffly, she was certainly grateful to the artist for the priceless professional lessons he taught her. When she visited a 1966 exhibit of Falk’s work at the Moscow Division of the Artists’ Union on Begovaya Ulitsa, she left the following message in the guestbook: “Looking [at] Robert Rafailovich’s work makes me feel like I’m reliving my youth and my life in Paris, where R.R. so often dressed me down for doing it wrong. My dear, unforgettable friend and comrade in painting... T. Verkhovskaya.”[2]

The manuscript of the newly published memoirs remains in the hands of the artist’s descendants. The text is presented in edited form based on a copy transcribed by a relative of Tatiana Verkhovskaya.

Yulia Didenko

- Yevgeny Vladimirovich Hirshfeld (1899-1941) faced political repression soon after he arrived in the USSR from Paris. He was arrested in May 1939 and shot by firing squad in May 1941, but later rehabilitated on August 18th, 1956.

- Citation: Guestbook of the R.R. Falk Exhibit at the Moscow Division of the Artists’ Union (October-November 1966). Autograph. Russian State Archive of Literature and Art. Coll. 3018. Aids 1. Fol. 277. Pp. 4.

Robert Rafailovich Falk had already been living in Paris for a few years when we moved there in the spring of 1934. My husband had been appointed advisor at our embassy there. One day the wife of our consul came by and proposed that we took up an invitation to see Falk in his studio and take a look at his works. The idea was a tempting one.

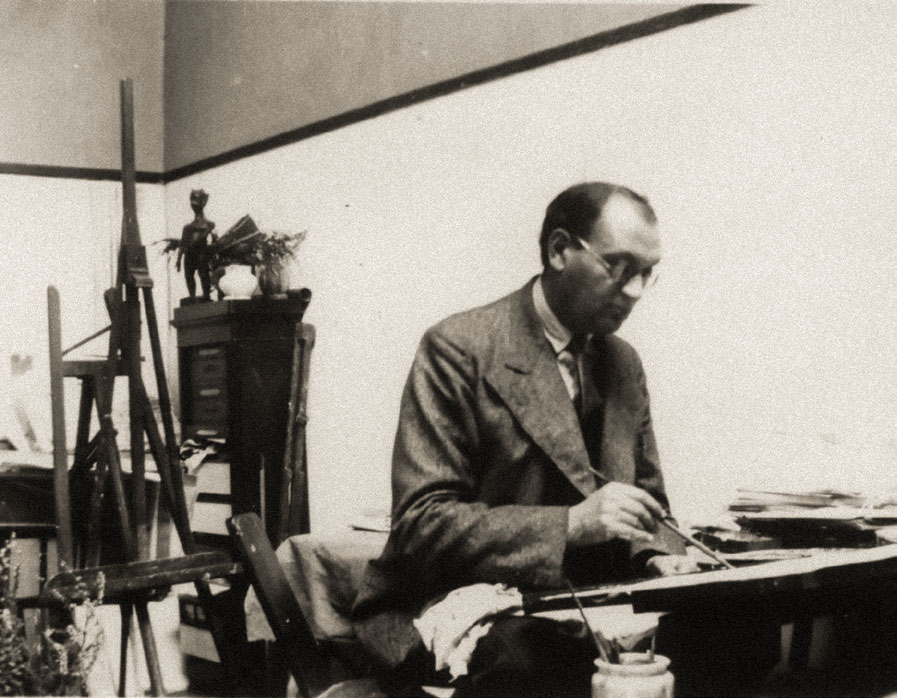

Robert Falk working at his studio in Paris. Mid 1930s

Photograph. From the archive of Kirilla Baranovskaya-Falk, Moscow

I remembered his works from the “Knave of Diamonds" exhibitions in Moscow, and once in Paris I had seen his landscapes (very reminiscent of his work in Moscow) at the Salon d'Automne in the Grand Palais.

In Moscow we were not acquainted. And here we were, visiting his studio. A tall, rather plump man opened the door for us, and asked us to enter in a pleasant, quiet, and slightly muffled voice.

Robert Rafailovich gave us a lengthy and interesting showing of his work, stopping to speak about nearly every piece. For the most part there were various landscapes, many of them urban, showing little cafes on narrow streets, the Seine embankments, canals with barges by the abattoirs. There was also the odd portrait. How many pieces there were! In some of them you could still feel that old Falk, the Falk he had been in Moscow, but now he had found something else, and somehow been cleansed of the inessential. The artist had begun to discover in him self something that was deep, new, and significant, but still tremulous.

How wonderful hat small summer landscape of a forest was, how silver-tinged and filled with light, with the germ of a trembling radiance which he would later master. Whenever I called by from then on, I always asked him to show me it. Where has it ended up, that landscape? It is possible that he sold it; after all, it was not easy for him to make a living there in material terms. Robert Rafailovich lived with his son Valery and gave lessons in drawing and music (he was a wonderful pianist).

I remember how he mentioned somehow in passing that he was working at a film studio on the film “Taras Bulba",[1] which was then being made with Danielle Darrieux and a famous German actor in the role of Bulba - Paul Wegener, if I'm not mistaken.

Robert Rafailovich asked to see my own work. I hadn't painted for nine years at that point; I had been working in theatres instead. In the first days after my arrival in Paris I had bought a small, folding easel and a paintbox, along with other tools of the trade. Gingerly, I started to paint. That was how our friendship began.R.F. was a wonderful teacher[2] - I realized that very quickly. Rather than instructing you, he guided you imperceptibly towards what you needed to see and how you needed to see it. His eyes feasted lovingly upon everything around him, and what's more he had the capacity to communicate that to his interlocutor. He took me regularly to museums and exhibitions, patiently listening to my naive criticisms, mildly explaining how to see and how to understand. He clearly loved to take people under his wing and to guide them, but at the same time without any sense of forcing his opinions on others. R.F was very quiet, but if he did say anything it was convincing and to the point.

We began to have sketching sessions together. Very often a call would come in the morning: “Would you like to go see a cafe were Lenin and a crowd of Parisian Bolsheviks used to gather?" Well, of course I would! And so off we went. The owner of the cafe was still living, and remembered Lenin well, along with many other patrons. Everything was just as it had been in the room upstairs that the owner let out for meetings and parties. He didn't charge a fee for the room - instead, everyone who came would order something, a glass of beer, a cup of coffee. It was often the case that a meeting couldn't take place because somebody had no money. We went up the squeaking wooden stairs and Falk sat in the centre of the room with his back to the window. He had gouache with him, so he made a sketch of the room.

In 1935 Robert Rafailovich proposed that Lyubov Kozintseva (the wife of Ilya Ehrenburg)[3] and I should make sketches of nude models in his studio. We worked in a group of four: Lyubov, Falk, Valerik (his son), and I. The first model was an exquisite strawberry blonde young woman with very fair skin. She sat simply and naturally. The others painted in oils while I was timid and used watercolours. The next model was a very beautiful brunette, with a mother-of-pearl body. We painted her for a much longer time, and this time I grew bolder and painted in oils. Falk didn't say a word to anyone, but all the same kept an eye on our work.

I remember that Lyubov and I stood together chatting while the model had a break. We were both brunettes; she was in a lemon-coloured knitted blouse while I wore a red sweater with a high collar. Falk, smiling, was watching us. “What I'd like is to paint you both together, just like that, just as you are standing now." Lyubov said nothing, and nor did I. It might indeed have been an interesting piece, but it was not to be.

He did paint me in the end, though, at my home in a black hat with a large ostrich feather and a cardinal-red blouse, against the background of a mahogany cabinet. From time to time he asked me to tell him something. Clearly, the frozen pose and vacant gaze of the model dejected him. He frequently cleaned away what he had done and started afresh. One day he did not come and the sittings ceased; the portrait remained unfinished. Mr. Falk was very dissatisfied with the painting, which he spent a long time over. It has not survived - apparently, he recycled the canvas for another painting, as was his wont if a piece was not to his liking.

These collective painting sessions at his studio did not long continue; the second model was our last. Perhaps Robert Rafailovich wanted to work alone. But we did start to meet again for sketching, working on the streets of Paris and outside the city.

One time we set off for the Seine embankment at Pont Marie[4]. It was the second time that we went there. The first time we were caught in a heavy downpour - how fun it was to take to our heels amid jokes and laughter. We larked like boys, leaping across puddles.

The second time was a success - there was a blue mist on the water, as there often is in Paris, and the ancient, hump-backed Pont Marie looked so beautiful. We always worked far apart. Absorbed in my work, I neither saw nor heard anything until a harsh, angry shout interrupted: “What are you doing?" I was afraid to look around, to see the fright ening face filled with rage. “They're not oils, you can't smear them with your fingers!" I lost my cool at that point and in a fury snatched up my portfolio and stormed off. When I got home, I laid the study on the table, but I could still see the bridge before me, standing in the blue mist, with the houses that I had managed sketch out stretching beyond it along the embankment. Trembling, I began to continue from memory.

I didn't hear the door opening, nor Falk entering quietly. He stood, silent, behind me.

I didn't even notice him. He saw, of course, how I took up paint from the palette with my fingers and applied it to the study. “Oh, paint how you like, use a splinter if you must!" he said in a cheerful voice, and we both started to laugh. Peace was made. Yes most probably that is my best gouache. How useful anger can sometimes be. That was our first quarrel, but unfortunately not our last.

I don't remember the exact year that the Air Show was held in Paris - it was 1935 or 1936. Our famed aviators arrived to take part, and one of them turned out to be an admirer of art. When I met him, I proposed that he go and take a look at Falk's works. That was the beginning of Falk's acquaintance, and later friendship, with Andrei Yumashev. Falk always showed his pieces very willingly and generously, without cherry picking. We spent nearly the whole day at his place, and we would have spent even longer looking at the paintings if dusk hadn't fallen.

Robert Rafailovich knew Paris well. He used to take pleasure in bringing me to various areas which he had already painted or was planning to paint. One day we had gone rather far, and on the opposite bank there was a whole forest of towering, smoking chimneys. It was the famous Lefranc Factory, which produced everything an artist could need, from paints to easels to portfolios to all sorts of other things. It was indeed a majestic place, that Lefranc Factory. I still have the frankly bad sketch I made of it, though I do not remember Falk's. He painted the riverbank, rather than the factory.

We visited the Parc Montsouris to paint yet another of Lenin's favourite places.

It was 1937, and the weather was warm with the taste of coming spring. We had long intended an expedition to Longjumeau, a town around 20 kilometres from Paris where Lenin and Krupskaya had once lived. There was no rain forecast, and the light was good and tranquil. There was a chill in the air, but that didn't bother us. I asked for a a car to take us there, and so we were standing on the street in the cosy little town, with its small, red-roofed houses. We took in our surroundings.

It was from here that Vladimir Lenin used to cycle to Paris on business, returning the same way. The road passed along the foot of a mountain, and one day the daring cyclist was struck by a car. Luckily there was no harm done to the rider, but the bike was not so fortunate. From then on he had to take the train. How little money the pair of them, Lenin and Krupskaya, had back then, and how young and unassuming they were.

All these thoughts galloped through my mind when I gazed at the small, single-storey house with its tiny front yard. Falk painted an exquisite silvery sketch of the house and fapade. How we froze then, working on the street! “We should warm up, let's go have a look at the cathedral." The cathedral was indeed beautiful, and in certain places there were metal gratings in the floor from which warm air issued. It was nice to stand on the gratings and warm up gradually, looking round. People praying sat on the benches, a mass was underway. The stained glass of the long lancet windows were marvellously beautiful; some sort of unreal, magical light streamed in. The quite music of the organ sounded like the music of that light. We returned home by train.

That summer [of 1937] the World Fair's was to open, and in spring work began on constructing the Soviet pavilion and delivering the exhibits. When the pavilion was nearly built and the crates from Moscow had already arrived, a handful of artist-decorators came over too, but not many. There was a clear manpower shortage. My husband was appointed to assist the chief commissar of the Soviet pavilion, and he proposed that I work on it. The hall of art fell to me. I proposed that we invite Falk, who started work in the next hall. There was an incredible amount of work to do - we were trying to open the pavilion before the Germans, whose pavilion stood opposite. We snuck in there once, on the quiet, and had a quick look round. Yes, it was hard to fault: everything was solidly done and looked great. We, however, wanted to make ours far better and more interesting.

At last the crates with paintings arrived. On their journey all the watercolours got unglued and slid down in their frames under the glass. The top brass was informed immediately, and once permission was received, the watercolours were removed and handed over to Falk to be properly re-mounted and re-framed, which was accomplished very quickly. We had to work nights, drinking an unbelievable amount of black coffee to keep us from sleeping. Each day we had time for only two or three hours of rest. News arrived that two wagonloads of arts and crafts (including bone-carvings from the North, fur-skin pieces embroidered with beads, hand embroidery, lacework, wood ware) stood waiting undispatched - should they be sent or not?

I knew the commissar[5] Ivan Mezhlauk[6] well, so went to see him and argued the case with passion and entreaties - they needed to come. He heard me out with close attention and sent a telegram to Moscow at once - and arrive they did. On the eve of the exhibition's opening everyone was on their last legs, no-one slept, but everything got done. It was worth it - those arts and crafts were the trump card of our pavilion. All the visitors crowded around the mirrored cabinets and display cases with the products of our craftsmen and marvelled at the taste and charm of the work.

Robert Rafailovich worked in the hall, where he hung with great taste all imaginable kinds of fabric. At that time the twentieth anniversary of Soviet power was just approaching. Behind the statue of Stalin stood a semicircle of columns made of light-coloured fabrics, lit very deftly from within. “Come with me, I'll show you a wonderful piece by Serov," said Falk to me one day. “‘Girl in the Sunlight', it's called." That portrait of Lvova[7] hung in the flat of her son[8]. It was the well-known portrait of Serov's cousin (born Simonovich), who was already at that stage married to Lvov. It is reproduced the monograph on Serov edited by Grabar. Falk told me that the portrait had been in a terrible condition, the paint crumbling and cracked. They gave it to the Louvre for restoration and here it was, back on the wall.

We stood, astonished, with goosebumps of delight. A charming face gazed out at us, lit by a double light; she gazed out with her wonderful violet eyes, with her luxuriant strawberry-blonde bush of hair, wearing a simple white camisole. Her son, lifting the lamp high with both hands, lit her from the right- hand side... I could talk only in a whisper, so overwhelming was the impression it made on me - this painting could not have been in a terrible condition, it was as fresh as if it had been just painted. I wanted to cry from delight. “You are like your mother," I said to the son in French, knowing that he did not speak Russian. “So they say", he answered. “Take the lamp off him, he's tired," I said to Falk, in Russian this time. And all of a sudden, the son announced in French: “Don't worry, madame, it's no effort." Mr. Falk and I were rather abashed. He may not have been able to speak Russian, but he certainly understood it. And we had been gossiping the whole time about how he, most likely, had no idea of the treasure he possessed in this portrait.

A few days later we went to meet the Lvovs. They lived near Paris, in a place whose name I don't know.[9] Robert Rafailovich studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, and remembered Valentin Serov most fondly of all. That was why, when in Paris, he tried to locate Serov's relatives,[10] and that was also how he found the “girl in the sunlight."[11]

They lived in a wooden house, which reminded me of the dachas around Moscow. The rooms were rather bare and poor; the walls were decorated with many small drawings and sketches, as well as a fairly large study for a portrait of Lvova. She herself was standing right next to it.[12] Her figure was very full, and she had greying strawberry-blond hair, an endearing round face and large, sad prominent eyes. “These are all his drawings and sketches. He always gave them to me willingly, as I never refused to sit for him," she said, smiling kindly at us. In the other room there was a tall old man sitting down.[13] “He is very deaf," warned Lvova. He greeted us from his armchair, and I understood that he might not be able to walk. He suddenly began to speak very loudly, as deaf people do: “Masha, stand by the portrait." At that moment we were gazing at a portrait of a delightful young woman. “Stand there," he repeated, insistently. She waved her hand, but obeyed. “Look at the resemblance! Smile, Masha," and a sorrowful grimace traced itself on her withered lips. What a love! He sees her just as she was then, and indeed it might be a good thing that he sees badly. He is very old, after all.[14]

Saying goodbye to the old man, we went out into the garden. Mr. Falk began talking with Lvova about what needed to be done to ensure that none of the pieces were damaged, and that she needed to write a will instructing that everything she had, along with his [Serov's] works, be transferred to the Soviet Union. I don't know if she managed to do that; I doubt it. The portrait is there, after all, with the son,[15] and I don't think he would have parted with it.

Robert Rafailovich played the piano well, and when he came to visit he would approach our instrument with pleasure, taking up my large volume of Chopin's mazurkas and waltzes bound together with Mendelssohn's “Songs without Words". He sometimes suggested that we hold a musical evening. On those occasions he would arrive with great ceremony, with a portfolio under his arm. He liked very much to play Schubert and Schumann. The musical evenings generally took place after work, and I used to gather together all the musically inclined embassy workers. Everyone sat where they liked, and the atmosphere was pleasant and cosy: a few of the women knitted jackets uninterruptedly, while others, sitting on the couch with their legs tucked beneath them, relaxed and daydreamed. I listened and sketched the reactions of the audience. It was at one of those evenings that I made my pencil sketch of Falk playing Schumann.

The ridiculous and hideous Trocadero was demolished, and in its place a snow-white palace was built to a strictly classical design, in which an exhibition of masterpieces of French art was held. This was at the same time that the World's Fair opened around the Eiffel Tower.

Early one morning, when the air was pure and the sun not yet very bright, we set off to see it on foot. The halls were still empty - they were spacious, and the light was ideal. The paintings were hung not very high in a single row, well spaced out. It was here that I first saw Soutine's famous “The Little Pastry Cooks" and the still life “Carcass of Beef". I was blown away, as if struck by lightning. So this was art, art in its pure, maiden state, without narrative. Falk was openly enjoying my confusion. He smiled mysteriously and called me further. The next hall had early pieces by Utrillo, Picasso, Matisse - all of France's young art. We couldn't stay long at the exhibit, and soon left.

That was my last meeting with Falk in Paris. That summer Robert Rafailoivich and his son went to Moscow. The next time we meet it was in Moscow, and a year and a half later...

Preparation of text, publication and comments by Yulia Didenko

- The film mentioned here was one of the first adaptations of Nikolai Gogol’s tale of the same name - an Anglo-French feature film “Tarass Boulba” / “Taras Bulba” (a GG Films production; directed by Alexis Granowsky, screenplay by Pierre Benoit, Fritz Falkenstein and Carlo Rim, dialogues by Jacques Natanson; starring: Harry Baur (Tarass Boulba), Jean-Pierre Aumont (Andrei Boulba), and Danielle Darrieux (Marina); 87 minutes running time; press screened on the 5 March 1936 in Paris). In 1935 Falk and his son Valer y made sketches for the film’s costumes. Falk wrote in a 1935 letter to his mother: “...my work in cinema continues. <...> They are very satisfied with me. I’m earning enough for Valerik and I to head off on holiday for a month and a half, or even two. As before, he is of great help in my designs for the cinema.” (quoted from: Falk, Robert “Conversations about Art. Letters. Memories of the Artist”. Moscow, 1981. P. 147).

- “Strange or not, I am (with no false modesty) an outstanding teacher, though I cannot stand to teach, to preach the truth and ways of art to ladies and girls” (From Falk’s letter to his mother, Maria Falk 1931 (?) // The Russian State Archive of Literature and Art. Fund 3018, inventory 1, item 157, sheet 19.

- Lyubov Mikhailovna Ehren- burg- Kozintseva (1899/1900- 1970) was an artist and the second wife of the writer Ilya Ehrenburg, as well as being the sister of the cinema director Grigori Kozintsev. Falk painted her portrait in oils in Paris (1929, private collection, St. Petersburg), as well as a range of portrait drawings.

- The Pont Marie is one of Paris’ oldest bridges, joining the tie Saint-Louis and the quai de l'Hotel de Ville on the Seine’s right bank.

- In the certificate issued to Falk as a participant in the exhibition the commissar is indicated as Evgeny Hirshfeld.

- 1.1. Mezhlauk (1891-1938) was a Party and political figure. From 1936 to 1937 he was head of the All-Union Committee for Higher Education under the Council of People’s Commissars of the Soviet Union. He was arrested in December 1937 and shot in spring 1938.

- Serov’s painting “Portrait of Maria Lvova”. 1895. Oil on canvas. Musee d’Orsay, Paris.

- See about him in comment 15.

- Neuilly-sur-Marne, near Paris.

- By Falk’s account, the encounter with the painting was unplanned. The artist was advised to take his ill son Valery to see “a certain elderly doctor. He lives 25 or 30 kilometres from Paris and is a very old man, about 80 or 82. So off we went, and he met us along with his wife, a little old woman of 70. I suddenly realise that hanging on the wall of the room is a very familiar portrait - a girl in front of a cabinet filled with books. It was an early piece of Serov’s, shrouded in a special poetry which later abandoned him. The old man asked us: ‘My wife is just like the subject, don’t you think?’ It turns out that Serov painted her 47 years ago! She is his cousin, and as it happens she is also the subject of my very favourite piece in the Tretyakov Gallery, ’Girl under a Tree’” (From a letter from Robert. Falk to the artist Alek- sander Kuprin. Paris-Moscow. February 1935. Autograph. // The Russian State Archive of Literature and Art. Fund 3018, inventory 1, item 147, sheets 19-19 obverse.

- The subject of the painting is Maria Simonovich - the model for Serov’s painting “Girl in the Sunlight”, in the Tretyakov Gallery (gifted by her to the Tretyakov Gallery in 1940). See the next note for more biographical details.

- Maria Yakovlevna Simonovich (in marriage Lvova, 1864-1955) was a sculptor, memoirist, and a cousin of the artist Valentin Serov. In 1890 she left Russia to study in Paris, where she married and settled permanently. Serov painted the portrait on one of her trips to Russia, in 1895. When she first met Falk in 1935 she was 70 years old.

- Solomon Keselevich Lvov (1859-1939) was a clinical psychiatrist, head doctor of a psychiatric hospital in Neuil- ly-sur-Marne (near Paris), the husband of Maria Simonovich, and the father of the microbiologist Andrey Lvov.

- In 1935, when he first met Falk, Solomon Lvov was 76 years old.

- Andre Michel Lwoff (19021994) - was a French microbiologist, a laureate of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965 (jointly with Frangois Jacob and Jacques Monod), and son of Maria Simonovich and Solomon Lvov. After the death of his mother he brought Serov’s portrait of her to the Musee d’Orsay, where it is to this day.

Sketch to an unfinished painting (not preserved). Lead pencil on paper

Private collection, Moscow. First publication

Gouache and watercolour on paper. 38 × 15.5 cm

Private collection, Moscow (previously, collection of Tatiana Verkhovskaya, Moscow). First publication

Gouache on paper. 39.7 × 53 cm

© State Historical Museum, Moscow. First publication

Oil on canvas. 60 × 71 cm

Private collection, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 96 × 64 cm

Private collection

Oil on canvas. 61 × 50 cm

Private collection, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 98 × 80 cm

Private collection, Moscow (on the reverse side of the Painting “Woman in a Cap (Elizaveta Potekhina)”. 1917)

Lead pencil on paper. 29.3 × 21.1 cm

© Yaroslavl Art Museum. First publication

Photograph

Oil on canvas. 90 × 59 cm

© Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Gouache, watercolour on grey paper. 31.9 × 41 cm

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts