Tears and Smiles in the Graphics of Igor Smirnov

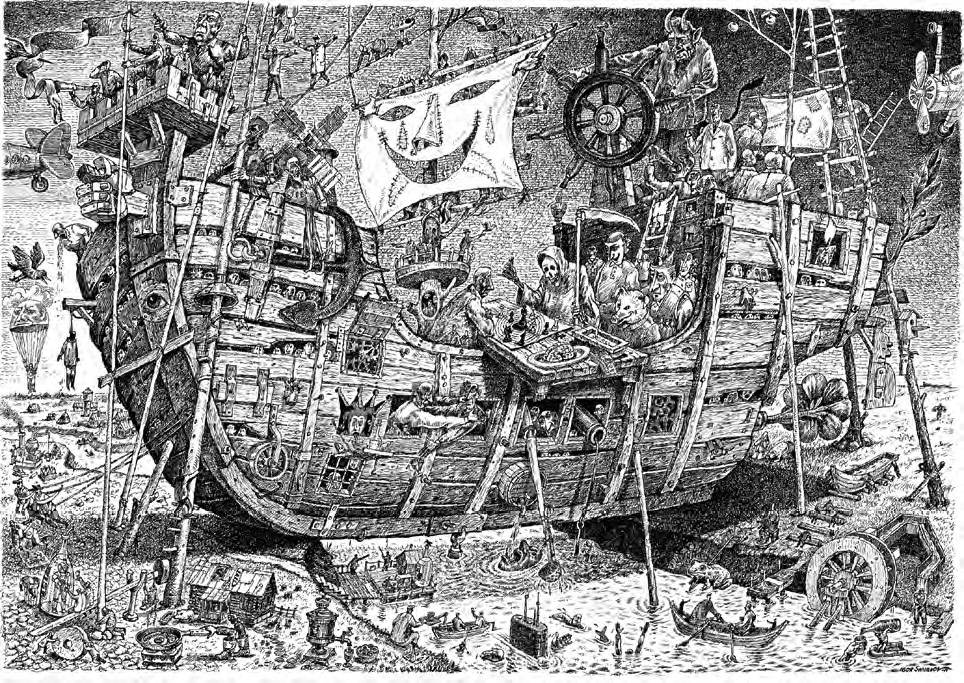

The acclaimed artist-caricaturist Igor Smirnov marked his 75th birthday this year with an exhibition that ran through July 2019 at the Russian Academy of Arts. Titled “This Is Us!”, the show brought together some 80 of his caricatures and graphic works, including pieces drawn from his renowned series “All About Don Quixote” and his recent “Ship 1” and “Ship 2”.

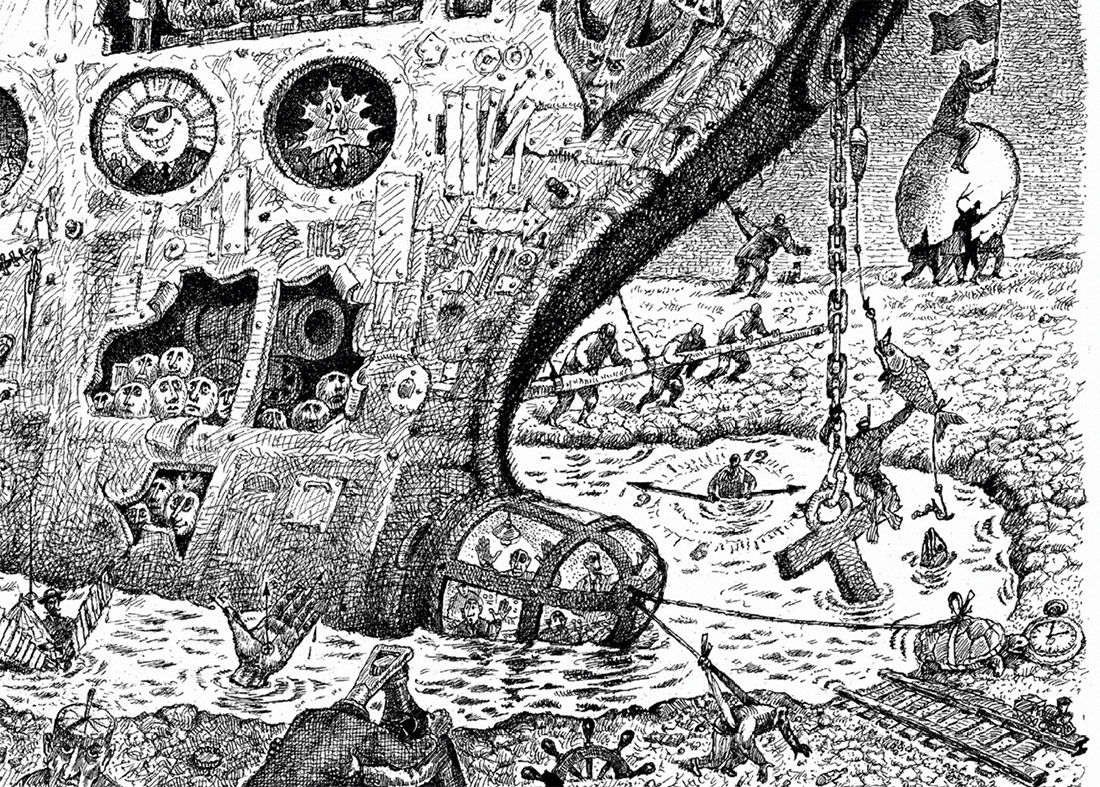

Ship 2. 2018

Ink and pen on paper. 70 × 100 cm

The work of Igor Smirnov is a rare example of graphic art that combines a superb command of different techniques with a complex synthesis of layers of meanings: their impeccable, inventive form hides many things - social commentary and philosophy, elements of comedy alongside hints of tragedy, the concerns of the immediate moment and issues of lasting importance. He is an undeniable master of caricature and so-called “problematic" graphic art, a trend that presents not so much the humorous entertainment characteristic of mass culture as an intellectual, often high-brow art that invites considered contemplation and even an element of “creative participation" from the viewer.

Born in 1944 in Moscow, Smirnov has lived in the Russian capital all his life. He has created several thousand graphic pieces, which started to appear in the 1970s, first in the Soviet press and later in publications of contemporary Russia. He was still a student at the Moscow Art College “In Memory of 1905" when his work was first printed in 1971 in “Krasnaya Zvezda" (Red Star, the official newspaper of the Soviet Ministry of Defence), an event that he considers the start of his artistic career. Smirnov has since won more than 60 international awards, including diplomas and prizes at competitions of satirists and humorists, such as Italy's Festival della Satira - he received the “Satira Politica" prize in 1988 from Italian foreign minister Giulio Andreotti - and professional gatherings in Warsaw, Havana, Melbourne, Ancona and Istanbul, where the prize was awarded to him in the city's Caricature and Humour Arts Museum, as well as medals from professional bodies such as the Sociedad Mexicana de Caricaturistas (Mexican Society of Cartoonists). The artist's individual pieces are held in private collections and have been reproduced many times in exhibition catalogues and other publications, solid indication of the international recognition that Smirnov enjoys.

A full member of the Russian Academy of Arts and a member of France's L'Academie de l'humour, Smirnov is well-known in the Russian professional community of caricaturists and among his colleagues from the “guild of graphic artists" of the former Soviet republics. While maintaining the socially and politically engaged approach that distinguished caricature first in the Russian Empire and then later in the USSR, Smirnov at the same time keeps himself at a distance from real life, something that allows him to transcend the boundaries of the genre and create works on a larger scale in both form and substance. His works often highlight not immediate social and political concerns but matters of broader humanist, existential and civilizational nature, along with other topical underlying messages that are recognizable for contemporaries. He has often compared his role as a satirist to that of a doctor, for whom “reaching a diagnosis is a professional duty".

Smirnov's art is ambivalent. On the one hand, his caricatures are distinguished by their genre-specific keen social awareness, something conveyed through repetitive archetypal intertextual historical and cultural visual markers that engage, subtly or directly, with the political life of society. On the other hand, his graphic work is an example of artwork that, through its use of narrative and compositional, purely artistic techniques, addresses much more complicated questions - life and death, freedom (and the lack thereof), the meaning of existence and absurdity, solitude in the crowd. All this characterizes Smirnov as not only a caricaturist who always hits his target but also as a graphic artist with a distinctive visual idiom and a range of subjects that have a lasting importance to him.

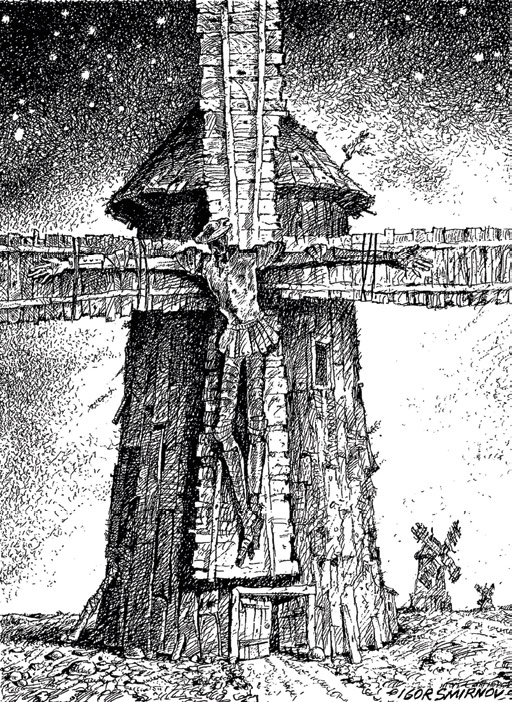

The defeat of a materialist concept of the world and of humankind's development, one in which rational, positivist discourse prevails over any spiritual, non-systemic element, does not always amount to the victory of good over evil, or any sense of coming closer to freedom. As the artist's works paradoxically show, this world in which angels fly around on wings stuffed with the souls of those who have died naturally (or unnaturally) has no place for altruists or romantics, for heroes such as Don Quixote with his “tilting at windmills", in its absurd and unfair reality. The macrocosmic element in Smirnov's compositions is complex: often overtly hostile to the individual, it creates around it a secondary civilizational reality, one which only very rarely brings anything that approaches happiness, peace of mind or “lightness of being". Smirnov's Don Quixote is a symbol of the desperate struggle of the good side of human nature with the destructive chaos of the noosphere, an environment in which social cataclysms destroy the vibrant, creative, soft and sympathetic energy of humanity. The crucified Don Quixote is an ambiguous image that is open to various interpretations, but at the same time it is a compelling and very specific rendition of the tragicomic idea about the nature of perpetual sacrifice in the struggle for goodness. His series of drawings devoted to Cervantes's famous hero is arguably Smirnov's finest creation.

Crucifixion. 2019. From the series “All About Don Quixote”

Silk screen printing. 32 × 26 cm

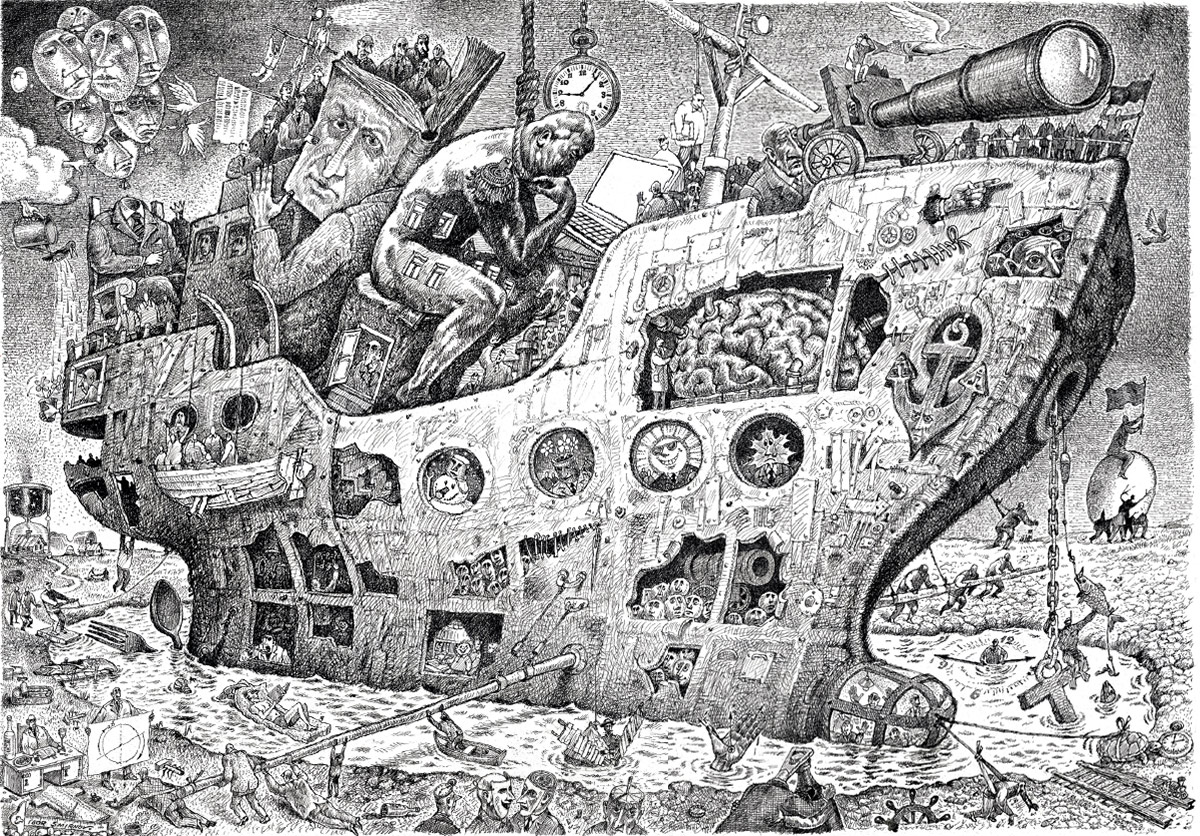

In recent years the artist has been concentrating for the main part on pictures of a complex composition, whose arrangement of inner space can be said to resemble that of Hieronymus Bosch. Graphic pieces such as “Time" (2017) and the two variants of “Ship" from 2018 present a masterful fusion of socio-political commentary and superbly crafted surrealist images and motifs that are vivid in their grotesquerie. “Ship 1" has a plethora of intricate details that combine to form a coherent picture of this strange vessel, with its seemingly innumerable passengers and other figures somehow caught up in the process that goes on around it.

Barge haulers for our time

Closer examination of some of the details of “Ship 2" helps to illuminate something of the artist's underlying conception. At the extreme lower right-hand corner, a man and a tortoise seem to be attempting to haul the vessel with a rope, an element that brings with it its own cultural associations. In Russia before the Bolshevik revolution, such work was done by hired labour, barge haulers, of whom we know today from works of art such as Ilya Repin's famous early painting “Barge Haulers on the Volga" (1873, Russian Museum) or Nikolai Nekrasov's 1860 poem “On the Volga". In Smirnov's piece these “new" haulers are not dragging the vessel along any river bank but rather attempt to pull it out from an expanse of water, some mini-ocean or pond in which a variety of activity, both marine and otherwise, is happening. However, there is no sense of any current, against which those barge haulers of old had to struggle, on this aquatic mass. The second figure concerned, the tortoise, complements the general picture, which can be seen as a metaphor for a state of life in which the joint efforts of man and tortoise can be interpreted as the slow futile efforts of some huge colossus against the unconstrained laws of nature.

Not for nothing do people speak about someone being “slow as a tortoise" while - further stretching this loosest of analogies - the famous song “Vladivostok 2000" by the popular Russian rock group Mumiy Troll (lyrics and music, Ilya Lagutenko) has a line that refers to “rails crawling out of the pocket of the country". The same right-hand corner of Smirnov's “Ship 1" has a rail that indicates the direction in which the ship might travel, were the man and tortoise able to drag it out of its pond. But how can this rickety, immobile boat transform itself into some sort of high-speed train? No matter how hard they try, this odd couple will never manage to complete this transformation. More than 150 years ago, Nekrasov wrote in his poem about the horrible labour of the barge haulers: “Like him, you'll die without words / Like him, you'll be lost in vain / This is how sand sweeps over / Your footprints on this strand / Which you tread yoked / Looking no better than a convict in chains / Repeating the sickeningly familiar words / Forever the same heave- ho!". Smirnov's etching, his surrealist portrait of our times, shows the continuing relevance today of Nekrasov's lines to these “new" haulers. The tortoise hauling the ship also has a pocket watch, an obvious symbol of time (though perhaps, too, an allusion to the March Hare of Lewis Carroll's “Alice's Adventures in Wonderland"), while a little behind it, various human figures seem to be trying to navigate the boat from the glass windows of what might be the cockpit of an aeroplane.

Rodin’s “The Thinker” as helmsman, Tsar-the-Father

The desire to understand how to steer this ship makes the viewer carefully examine the figures on its deck: the congregation of Smirnov's characters - both human and far removed from humanity - is numerous, the huge figure of Rodin's “Thinker" prominent at its centre. The very fact that this famous statue appears amidst the other creatures on the ship is essentially surrealist, thus evading any simple interpretation. And yet, when coupled with this immobile ship, Rodin's “Thinker" becomes easy to understand: we can see that, if this figure were to attempt to rise to its feet, the slip knot around his neck, which seems to be weighted by another, larger pocket watch, would become a noose... If he goes on sitting there and thinking, however, sooner or later he will become mature enough to understand the general principles of how the mechanism works, thanks to which knowledge the spring will “straighten" and the boat be set in motion.

But how much longer will this take, and how many haulers' lives be lost? Rodin's statue is a symbol of the workings of the human intellect, inconspicuous but invisibly present within. Smirnov's “Thinker", meanwhile, is an image showing some more hidden energy, inasmuch as he is also a commander, the appearance of the epaulette on his shoulder far from accidental, evoking as it does the Tsar-the-Father, the monarch's rule or the cult of a leader (the imaginative viewer may even detect the features of Joseph Stalin in the Thinker's visage). Another unusual element appears in the windows on the Thinker's body, an image that generates anxiety: there might be something threatening hidden behind the glass, though at the same time windows expand the substance of what we see.

In the iconography of Russian art, similar sensations are provoked by compositions such as Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin's “1919. Alarm" (1934, Russian Museum) or Igor Obrosov's “1937. Mother and Father. Waiting" (1967), in which such windows play an important psychological role in conveying the feeling of an era in which fear is generated by an inevitable future that will appear through such glassed-in entrances and usher the painters' subjects away towards the heavy black automobiles of the security police. The perpetual fear and dread felt by the “little man" in relation to the bureaucratic apparatus, this state-as-ship, is neatly conveyed through the imagery of windows that resemble flecks of light on the body of the “Thinker" leader-commander. The compressed spring of the meaning of Rodin's sculpture is decompressed for us in this detail. This imagery in equal measure reflects the idea contained in Alexander Ill's famous aphorism “When Russia's Tsar is fishing, Europe can wait" (for which the pose of Rodin's “Thinker" is best suited) and a rendering of the more complex knot of relations that connect the Tsar-the-Father and his people, and the machinery of state that they jointly operate.

Ship 2. 2018. Detail “The Thinker”

Ink and pen on paper

Fishing and sinning

The process of creating any surrealist artwork is distinguished by a certain automatism, by moments when the subconscious comes to define the appearance of the world in a work of art. For Smirnov, however, it is intellect that almost always prevails over any irrational element: thus, “Ship 1", like many other of his works, features clear motifs that are surely deliberately introduced by the artist, one such example being the imagery of fishing that is here sublimated into a motif of Christianity.

Ship 1. 2017

Ink and pen on paper. 70 × 100 cm

Significantly, it was from the Latin navis (“ship") that the nave, or central part of a rectangularly built church, came to be known (with the shape of the nave itself referencing either the “ship of St. Peter" or the salvation of Noah's Ark: in 17th century Eastern Orthodox church architecture the arrangement of the detached belfry and the main church, joined by a gallery or a low elongated narthex, was known as the “ship design", the belfry above the porch serving as the prow). As an extension of that idea, the believers present in a church in some sense “commanded" that ship. But the rest of the details of Smirnov's picture, as elucidated above, show that this ship is going nowhere - it is stationary: the people cannot operate it because each is pulling in his own direction. Nevertheless people are fishing from its vessel's mast, out of its portholes. If we recall that in Christianity the fish, via the Ancient Greek ic- thus (ixQug), is a symbol of Christ, we are confronted with a strange, and sad, spectacle: we all are sinners, the artist says, showing us why humans cannot be perfect.

Igor Smirnov's creative will enables him to produce an art that has a special aura, a sort of art that is aesthetically tragicomic, allusive and humane, and always attractive to a thinking individual.

Etching. 32 × 26 cm

Etching. 32 × 26 cm

Triptych. Watercolour, ink, pen on paper. 70 × 100 cm each

Ink and pen on paper. 32 × 26 cm

Etching. 32 × 26 cm

Etching. 32 × 26 cm

Etching. 32 × 26 cm

Ink and pen on paper. 70 × 100 cm

Watercolour, ink, pen on paper. 61 × 83 cm

Colour pencil on coloured paper. 65 × 50 cm

Colour pencil on coloured paper. 65 × 50 cm

Watercolour on paper. 55 × 80 cm

Watercolour on paper. 55 × 80 cm

Ink and pen on paper. 70 × 100 cm

Etching, colour pencil. 32 × 26 cm