Staging the Future. Meyerhold and Golovin’s lost production of “The Nightingale”

On the evening of May 30 1918, opera lovers in Petrograd gathered at the Mariinsky Theatre to attend the Russian premiere of Igor Stravinsky’s “The Nightingale” (Le Rossignol/Solovei').[1] The audience dodged gunfire in the streets to make their way into this jewel box of Russia’s former Imperial Theatres, and what they witnessed on its stage that night was a painful reminder of their own collapsing social world: a satiric fairytale about a dying emperor, surrounded by fawning, buffoonish courtiers and an agitated populace. That Stravinsky’s emperor is saved, at the eleventh hour, by the healing power of art - metaphorized as the song of a nightingale - must have served only to underscore the destabilizing dread of their own recently deposed emperor’s uncertain future: imprisoned at the time of the opera’s Russian premiere, the Imperial family would be executed just six weeks later. It wasn’t merely an unfortunate play of resemblances that jarred. The highly experimental production, directed by Vsevolod Meyerhold and designed by Alexander Golovin, featuring an enormous cast which included the 14-year-old dancer Georgi Balanchivadze (George Balanchine), seemed to play deliberately on tensions between a fading past and an uncertain future, and between fiction and reality.

Meyerhold and Golovin’s staging concept combined proto-constructivist elements with sumptuous chinoiserie. Golovin's decor alluded both to fairytale exotica and to the Chinese Village in the Alexander Park at Tsarskoye Selo, the former Imperial residence to the south of St. Petersburg, where the designer resided at the time.[2] Planned for an Imperial theatre but presented in a Bolshevik one, the Meyerhold-Golovin production seems at once a last echo of the old world in the new, and a blueprint for the theatre of the future. In that anxious spring of civil war, this “fairy tale" must have both challenged the expectations and jangled the fraying nerves of a distressed and frightened audience. As one critic aptly remarked: “‘The Nightingale' has alighted in desolate, abandoned Petersburg at the wrong time, in the wrong place."[3]

Alexander GOLOVIN. Set design for the Porcelain Palace of the Emperor of China, Act II, “The Nightingale”. 1918

Private collection. © Sam Sargent Photography. Detail

Yet the opera had been long awaited by the Russian public. Dreaming of a triumphant return to his homeland, expatriate composer Igor Stravinsky had long hoped (and actively schemed) to premiere “Solovei" at the Mariinsky. But Diaghilev had snared the opera for the “Ballets Russes", and “Le Rossignol" premiered at the Theatre National de l'Opera in Paris on May 26 1914, in a double bill with Rimsky-Korsakov's “Le Coq d'Or".

With “Firebird", “Petrushka" and “Rite of Spring", his first three ballet scores for Diaghilev, Stravinsky had become accustomed to creating directly in collaboration with scenarists, choreographers and designers, their visions and staging ideas contributing to the very fabric of his scores. These partnerships had been pivotal in his remarkably rapid development as a composer, and he felt acutely the lack of visual collaborators as he laboured on his opera. He had enjoyed an exceptionally close working relationship with Alexandre Benois on “Petrushka", a paean to their St. Petersburg childhoods, with Benois contributing to the libretto, designing the sets and costumes, and co-staging the ballet with Michel Fokine. After many struggles in the creation of “The Nightingale", Stravinsky at last secured Benois as designer for the “Ballets Russes" premiere, and his involvement was crucial to the completion of the work.

Stravinsky never again worked with a designer so intensively, “demanding full descriptions in advance of the sets and costumes",[4] all detailed in the voluminous correspondence between the two. The composer seemed as influenced by the colours and staging suggestions of the director-designer as the latter was by the “fausse-chinoiserie" of Stravinsky's score, which gave Benois “an opportunity to express all my infatuation with Chinese art... The final result was a Chinoiserie de ma façon, far from accurate by pedantic standards and even, in a sense, hybrid, but undoubtedly appropriate to Stravinsky's music."[5] This intensely visual approach was mirrored in the work of Stravinsky and his librettist Stepan Mitusov, who drastically reduced the words from their previous drafts of Acts II and III.[6] The 1914 premiere production, co-staged by Benois and Alexander Sanin and choreographed by Boris Romanov, was a final prewar apotheosis of “Mir isskustva" (World of Art) aesthetics, achieving a result that Stravinsky described as “the utmost perfection".

But in fact the reviews and audience reaction were mixed, with “Le Rossignol" overshadowed by the other production on the bill, Rimsky-Korsakov's opera “Le Coq d'Or". It featured a highly innovative staging as a “ballet-oratorio" that split the roles between opera singers seated on the sides of the stage and ballet dancers miming the roles on stage. Benois claimed credit for this idea, both in newspaper interviews at the time and years later in his memoirs.[7] In the latter, Benois veered between high-minded defence of the concept as a model for transforming opera into a perfect World of Art Gesamtkunstwerk by reblending voice and movement, and far less admirably, confessing to aesthetic chauvinism in his preference for watching more “physically presentable" ballet dancers over large-bodied opera singers.[8] In any case, Benois' vision was directed more to the past than to the future: even his suggestion of placing all of the opera singers to the sides, dressed identically and arrayed on tiered benches, was not a futurist gesture but meant to evoke the ancient Russian lubok - a project entirely within the nostalgic and neo-nationalist agenda of the “Mir isskustva". And as music historian Richard Taruskin points out, the idea of combining the functions of singers and dancers was hardly new: “.the Benois/Diaghilev ‘Coq d'Or' could be looked upon as a revival of the court-opera ballets of the French grand-siècle. Given the long-standing Versailles-mania of the Miriskusniki, this is not a factor to be discounted."[9]

These flourishes clearly affected Benois' approach to designing and staging “Le Rossignol". And in fact the idea of splitting roles was in Stravinsky's opera from the very beginning; he and Mitusov had conceived the idea of the Nightingale being introduced in Act I simply as a voice from the orchestra pit, while the imagined bird flitted unseen in the forest trees onstage. In later scenes, the bird would be embodied by a puppet (artfully manipulated by a dancer in the eventual “Ballets Russes" premiere). When he became involved five years later, Benois extended the idea to the Fisherman as well, having the role mimed onstage by a dancer appearing upstage in his boat, while his aria was to be performed by a singer in the orchestra.[10] In the event, the star singers of the Imperial Theatres recruited to sing the roles refused to be relegated to the pit, and as in “Le Coq d'Or", Benois hastened to move them to the sides of the stage as a “decorative" element.

The Russian press, largely negative toward the Diaghilev enterprise in Paris, nevertheless trumpeted the innovations of the 1914 season. The Mariinsky sent a contingent to Paris to view the “Ballets Russes" incarnation of “Le Rossignol"[11] and after surmounting numerous obstacles, reached an agreement to mount their own production. Originally planned for the 1915-16 season and inclusion in the Mariinsky's ongoing repertoire, “Solovei" would make its Petersburg premiere only after staggering upheavals in Russian society - a World War, two revolutions and a Civil War, in the mind-numbing span of four years - and was performed just once before disappearing from view.[12]

Alexander GOLOVIN. Set design for Act III, “The Nightingale”. 1918

Private collection. © Sam Sargent Photography. Detail

That performance was the quiet death knell of an artistic era. In the months and years of post-revolutionary strife that followed, many of the artists associated with the opera - among them Stravinsky, Diaghilev, Benois, the intendant of the Imperial Theatres Alexander Siloti, the English (but St. Petersburg-born) conductor Albert Coates, and Balanchine - would be permanently scattered across the globe, early victims of the seemingly endless waves of 20th century diaspora. And those who, like Meyerhold and Golovin, remained in Russia, awakened to a new age, a transformed cultural life, and ever-more traumatic conditions.

The production's physical traces, too, were scattered. In the subsequent decade, Golovin's original designs for “Solovei" would largely disappear,[13] with only an incomplete set of copies of the costume designs preserved in the St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music. The production faded from historical view, dismissed as a minor work of a major director[14] whose name would be expunged from the record of Soviet culture.[15] The gradual resurrection of Meyerhold's aesthetic legacy beginning in the 1990s would have little impact on the historiography of his “Solovei". With its single performance, ambivalent critical response, and missing traces, the production has received scant scholarly attention.

But in the 1980s the “lost" cache of Golovin's original “Solovei" designs resurfaced in a private collection in San Francisco, after a decades-long journey around a war-torn world: from Russia to Western Europe, Asia, and finally the United States.[16] Though the designs were originally discovered (by their owner's heirs) in 1968, their provenance and significance was not fully recognized until 2005, when co-author Brad Rosenstein curated an exhibition of the designs at Davies Symphony Hall in San Francisco.[17] Continued investigation led to the conclusion that, far from negligible, Meyerhold and Golovin's “Nightingale" was a missing link between Meyerhold's pre- and post-revolutionary aesthetic, and a seminal force in the creative lives of its participants.

Considered on its own terms, Stravinsky's first opera is a relatively minor work in his canon. Its fractured composition over a six-year period, its starkly contrasting musical styles, its seemingly lightweight subject matter, and its premiere production as a somewhat muddled conflation of opera-ballet-oratorio have led to its frequent dismissal as an apprentice and hybrid work. But precisely these factors make deeper consideration compelling. The opera's evolution in the course of its creati on provides unique insight into Stravinsky's formative theatrical sensibilities,[18] and his subsequent transformation of the opera into both a ballet and a concert work point to the piece's importance as an aesthetic bridge within his oeuvre. The Meyerhold-Golovin production completes the tale of the opera's significance in the composer's complex relationship to his homeland, and bridges the Silver Age period of the World of Art, the “Ballets Russes", Meyerhold's investigations of synthesis and stylization, and the era of bold, post-revolutionary experiments to come. “Solovei" is a hybrid work indeed - and a pivotal one.

We focus here on the Meyerhold-Golovin production, with emphasis on its critical place in the development of Meyerhold's artistry: the lynchpin between his Imperial theatre aesthetic of 1917, and the cubo-futurist and, subsequently, constructivist work begun in 1918. The production is noteworthy, too, as the final collaboration of Meyerhold and Golovin: the culmination of a decade-long partnership in which the two men redefined 20th century theatre as the age of the director and the designer, and produced a new understanding of mise- en-scene, which altered the relationship of the actor to both audience and scenic environment. Internationally, Golovin was recognized for his designs of such “Ballets Russes" landmarks as “Boris Godunov" (1908) and “Firebird" (1910); in Russia, Golovin's collaboration with Meyerhold generated such milestones of stagecraft as “Don Juan" (1910) and “Masquerade" (1917). Together, Golovin and Meyerhold pioneered a bold use of colour and scenic space to convey theatrical mood and psychological states, and their staging of “Solovei" represents a culmination of these explorations. These designs are among the richest in Golovin's body of work.[19]

Golovin and Meyerhold

Meyerhold’s avant-garde experiments as a director with Vera Kommissarzhevskaya's Drama Theatre in 1906 and 1907 provoked critical backlash in the conservative cultural world of St. Petersburg. His detractors applauded his dismissal from that company in late 1907 - and were shocked to learn of his immediate engagement as a stage director for the Imperial Theatres, a bastion of artistic conservatism.[20] But it was precisely Meyerhold's “propensity for stirring up people" that appealed to Imperial Theatre director Vladimir Telyakovsky, who felt that this quality would prove “very useful in the State theatres".[21]

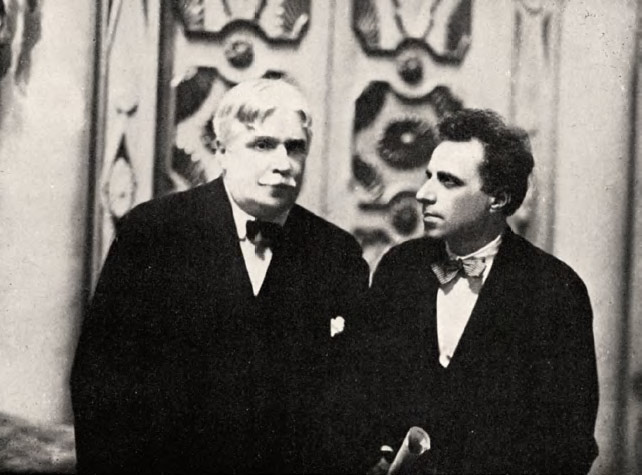

Alexander Golovin and Vsevolod Meyerhold. 1923

Photograph

It was Golovin, leading set and costume designer for the Imperial stages since 1900, who recommended Meyerhold's appointment.[22] Golovin had begun his studies in 1881 in the architecture department of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, shifting to painting two years later.[23] Though trained in the rigid realism of the “Peredvizhniki" (Wanderers), he much preferred his informal instruction in still-life with Vasily Polenov, which set him on a path (enhanced by studies in France, Italy and Spain) toward the latest innovations in Impressionism, Symbolism and the early stirrings of modernism. His work embraced an astonishing range of forms and media, from painting and ceramics to wood-carving and graphic design. In the 1890s he joined the Abramtsevo group - a fine arts and crafts colony founded by Savva and Yelizaveta Mamontov - immersing himself in traditional Russian crafts, decorative arts and interior design.

Golovin's parents, who died young, had engendered in him a love of music and theatre, and he received his first taste of scenic design working for Savva Mamontov's Private Opera Company. Mamontov, an industrialist, patron and producer with strong ties to Konstantin Stanislavsky, spearheaded a revolution in Russian opera (and, by extension, theatre) production by engaging leading contemporary artists to design sets and costumes. Mamontov's guiding principle, rooted in Wagner's notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk, was a collaboratively created, aesthetically unified approach to production resulting in a synthetic whole. At Abramtsevo, Golovin attracted the attention of the young Sergei Diaghilev, quickly becoming the senior member of Diaghilev's “World of Art" group, which was mining the past of Russian and European art to craft a forward-looking aesthetic.

Audiences and critics were somewhat baffled by Golovin's early opera and ballet designs, so different from the norm of generic sets and costumes cobbled together from existing stock. Golovin's bold, expressive work called attention to the designer as an equal contributor, provoking much grumbling about “art for art's sake". But Golovin had the early enthusiastic support of Alexandre Benois, artist, designer and prominent critic, and a leader in the “World of Art", who declared that Golovin's “set designs for ‘The Ice Palace' and ‘The Maid of Pskov' show us that he is a real artist, by the grace of God, a subtle poet and a great master... The set design becomes as sonorous as the music, catching up to it and with it serving a single purpose."[24]

In 1902, Golovin relocated to St. Petersburg, establishing his studio under the dome of the Mariinsky Theatre (an iconic masterpiece designed by Benois' grandfather, the architect Alberto Cavos), and from this moment a certain bitterness emerges in Benois' reviews: the younger artist clearly felt his rightful place usurped by Golovin. It did not help that Golovin was gaining confidence and control over his work and, with major new designs for such operas as “Carmen" and “Boris Godunov", garnering increasingly positive critical and audience response.

Golovin was evolving a personal approach to stage design that emphasized a strong central production concept and unified execution. He combined a realist's eye for detail with an Impressionist's passion for texture and light, and an architect's formal precision with a riotous sense of colour, developing a “colour score" unique to each production, which rendered psychological subtext through integrated use of colour in each scene and act.[25] Experienced in virtually every branch of the applied arts, he was at home with all aspects of design - set, costume, properties, light - working side by side with the skilled artisans of the Imperial Theatres, designing and crafting every detail, using the state's extensive resources to create a series of entirely new productions.

Golovin's collaborative method, which had its roots in Mamontov's Private Opera and become the norm within the “World of Art", proved challenging, even subversive, to the rigid hierarchies and traditions of the Imperial Theatres. Golovin's need for a like-minded collaborator spurred his recommendation of Meyerhold. And Telyakovsky, despite his conservatism, cannily sensed that the towering innovations brought to the Imperial Theatres in the 1880s and 1890s by such artists as Tchaikovsky and Petipa were already passe; a new generation was demanding an infusion of fresh ideas and creativity appropriate to a new century.

From their first collaboration - Knut Hamsun's drama “At the Gates of the Kingdom" (1908) - Meyerhold and Golovin recognized in one another a shared dedication to the creation of “pure theatricality". As with Meyerhold's “Hedda Gabler" (Drama Theatre, 1906), their “Kingdom" “departed from the realistic box-stage set furnished to reflect the hero's" social reality (in this case, “grim poverty"),[26] instead depicting “the holiday mood in the hero's soul", in the form of a “bright living room of ‘a luxurious palazzo',"[27] and dressing the hero and his friend “in pastel colours, as if modelling some fashion of the future".[28]

Although the result was not a critical success, Meyerhold and Golovin were mutually delighted by their first collaboration. The production laid bare questions of staging with which they would grapple for the next 10 years. Principal among these was how to break down the decorous distance between actor and audience imposed by the grand proscenium stages of the Imperial Theatres. The second (which had preoccupied Meyerhold since 1905) was how to render the interaction between the acting body and the painted backdrop (which persisted from the 19th century, and which interested Meyerhold and Golovin for its intrinsic theatricality) as sculptural, plastic scenic expression. And finally, how to transform the actor's own relationship to space and design, making performers in every sense integral to the total work of art. Meyerhold and Golovin would find their answers in commedia dell’arte and opera; but the latter - opera - has too often been neglected in considerations of Meyerhold's development.

Meyerhold had never directed an opera prior to his work with the Imperial Theatres, but the form's emphatic conventionalism and theatricality made it a logical next step following his early experiments in stylization. He spent a year preparing for his first operatic production, Wagner's “Tristan and Isolde" (1909), immersing himself not only in Wagner's own musings on the “theatre of the future", but in the writings of contemporary theatrical pioneers such as Edward Gordon Craig, Adolphe Appia and Georg Fuchs, all of whom had been inspired to visionary leaps by the challenge of staging Wagner's work. Meyerhold cites all of these influences in his seminal essay, “Tristan and Isolde", a distillation of the theories he absorbed in his preparation and the conclusions he formulated through his production experience.[29]

In the essay, Meyerhold draws a direct connection between pantomime and opera, citing the close synchronization of music and stage action in the former as an ideal for the latter. He contends that the stumbling block in achieving this lies in the singers' tendency to root their action not in the music but in the libretto, which often encourages a realistic acting style antithetical to music drama. “Stylization is the very basis of operatic art - people sing... Music drama must be performed in such a way that the spectator never thinks to question why the actors are singing and not speaking."[30]

This approach to opera was consonant with the stylization Meyerhold had explored in such productions as “Sister Beatrice" (1906), in which speech, movement and plastic groupings were rooted not in naturalism but in the poetic rhythms of Maurice Maeterlinck's drama.[31] Meyerhold's enthusiastic embrace of opera seems to derive from the form's inherent play with theatrical convention, and the freedom this gave him to further his own investigations. In Wagner's staging ideals, Meyerhold finds a springboard for his own manifesto: “The artistic synthesis which Wagner adopted as the basis for his reform of the music drama will continue to evolve. Great architects, designers, conductors and directors will combine their innovations to realize it in the theatre of the future."[32] Meyerhold's work in opera continued to challenge the traditions of its staging. In his 1911 Mariinsky production of Gluck's “Orfeo ed Eurydice", for instance (designed by Golovin, choreographed by Fokine), key roles were doubled, shared between singers and dancers, the performers blending so fluidly onstage that voice and movement seemed to fuse into one congruent whole. That approach foreshadowed his even more adventurous “Solovei".

The design and staging of “Solovei”[33]

Like “Orfeo”, “Solovei" concerns the power of art to transcend death. The libretto, adhering closely to the Hans Christian Andersen fairytale upon which it is based, tells of a Chinese Emperor who, upon learning that the most beautiful thing in his kingdom is the song of a nightingale in the forest, calls for the nightingale to take up residence in his court. Upon receiving the gift of a jewel-encrusted, mechanical singing bird, the Emperor's interest in the living nightingale wanes, and he returns to the forest. But the mechanical bird breaks down; the Emperor falls ill; and only the return of the living nightingale and his natural song saves him from death. (The Nightingale is referred to as female in Andersen's story, but male in the opera's libretto.)

As the basis for his staging, Meyerhold took the opposite approach from “Orfeo", here splitting characterization between voice and body. The cast comprised three distinct groups: soloist singers, silent mimes and chorus. The key roles of the Fisherman and Death were doubled by a singer and a silent actor; the Nightingale, by a singer and a flying puppet. But rather than obfuscating the line between music and movement as he had done previously, Meyerhold accentuated it, setting his soloists “separately down front" (near or on the forestage), and his mimes “on stage", in the deep scenic space beyond the proscenium. The cumulative effect was of multiple planes of action and characterization. Aspects of Meyerhold's structure echo Benois' staging conceit for the Paris premiere and for “Le Coq d'Or" (which, in turn, could be said to have built upon Meyerhold's 1911 “Orfeo"); but the conception, execution and implications of the Meyerhold-Golovin “Solovei" would prove radically different.[34]

Three sets of documents - Golovin's ground plan, Meyerhold's blocking plan, and Golovin's set renderings - must be read in conjunction to arrive at a clear understanding of staging and design. The ground plan is skeletal; the set renderings, indications of visual effect (rather than blueprints): curtains, painted flats and scenic structures are dimensionally indistinguishable. Golovin's painterly rendering style is in keeping with an “impressionistic" design method developed by Meyerhold and collaborating scenic artists some 13 years earlier, during Meyerhold's directorial experiments at the Povarskaya Street Studio (co-founded with Stanislavsky in 1905). In doing away with scale models, Meyerhold had sought a lightness of technique that would in turn engender a more fluid collaborative process, facilitating ease of communication between director and designer, and accentuating a painterly aesthetic in scenic design. That impressionistic process lay at the core of the harmonious collaboration between Golovin and Meyerhold.[35]

The opera is set in a legendary China.[36] After a brief orchestral prelude (owing much to Stravinsky's idol, Claude Debussy), the curtain rises on a night scene, the seashore at the edge of a forest. According to the libretto, a Fisherman appears upstage in his boat and begins to sing in anticipation of hearing the Nightingale's song. The birdsong delights him and lightens his cares - he experiences it as an embodiment of the heavenly spirit that provides him with all he needs: sea, winds, fish, natural beauty. The Nightingale, unseen, begins to sing of the roses in the Emperor's garden, drenched in morning dew like diamond tears.

Meyerhold placed the soloist Fisherman (Georgy Pozemkovsky,[37] a leading character tenor) and Nightingale (Neonila Volevach,[38] a popular coloratura soprano), prominently upon the forestage, seated motionless on unadorned wooden benches, with music stands and sheet music before them. Upstage, silent performers embodied their roles in dance and mime.[39]

None of these silent performers is credited in the production's programme.[40] Such roles were often filled by students of the State Theatre School, and Balanchine's recollections bear this out. Their ranks had been much reduced, many students having fled the chaos of the capital. The School had closed twice in the wake of the February and October revolutions, and been commandeered for months as a Red Guard barracks. Barely surviving each upheaval, it re-opened just weeks before the “Solovei" premiere.[41] The extensive number of mimes and extras required for “Solovei" - approximately 60[42] - may also have been drawn from among Meyerhold's own students, and even from among sailors at the nearby Kronstadt naval base.[43]

Meyerhold's directing plan divides each act into French scenes by entrances and major arias, with Act I comprised of four scenes, each act unfolding in a unified time and place.[44] Meyerhold suggests that set changes be minimal and conducted (where possible) “au vista" (in view of the audience).[45]

Golovin's surviving scenic design for Act I consists of an impressionistic backdrop of sea and sky, clouds and rising sun. On stage there would also have been the suggestion of a seaside forest in the foreground.[46] The Fisherman's opening aria invokes the winds and heavenly spirits to bestow a good catch, expresses his longing for the song of the Nightingale, and conjures the beauty of nature. Closely following the libretto (“Pale, how pale is the young moon. / Morning light will break too soon"),[47] Meyerhold and Golovin lit this opening scene for “Night, near dawn..."[48] Meyerhold's directing plan takes careful note of every mention of light, calling for “a pale crescent moon" at the start of Act I, and “the falling of a star" as night gives way to dawn, revealing Golovin's backdrop, with its suggestive opening eye of a sun, its brilliant colours of sea and sky emerging gradually over the course of the scene. The designer and director's evocation of this natural world sets up a vivid contrast with the subsequent artificiality of the Emperor's court.

This distinction between nature and court may have partially inspired Meyerhold's unique staging, and his approach is characteristically layered. He creates, to borrow Dassia Posner's term,[49] refracted images, composed of conflicting signs. The silent Fisherman is simply dressed in blue cotton - a poor working man's clothes. The soloists' costumes, by contrast, are sumptuous, suggestive of Orientalist visions of power and privilege. To a striking degree, the singers' costumes clash with the implicit gestus of Andersen's characters (of the Fisherman's poverty, the Nightingale's simple authenticity), aligning them rather with the ornate world of the Emperor and his entourage. It is an uncanny slippage, the singers' own prestige as stars of Russia's former Imperial theatres at once bleeding into the fictional realm of power and privilege unfolding upstage, and yet oddly sundered from the vivid artistry pulsating behind them. The singers are placed outside the frame of the fiction, on the apron, the liminal space between audience and stage, turned away from the action and unable to engage with it; richly dressed in chinoiserie, they sit motionless on utilitarian benches - a constructivist element avant la lèttre.[50] In 1918 Petrograd, these tensions would have resonated with echoes of the tumultuous split between Russia's old and new worlds, between diminishing privilege and the rise of the worker. And yet, despite their elaborate costumes and underscored artistry, the singers, too, in this proto-constructivist frame, evoke workers even as they evoke the court.[51] Perhaps, too, they hint at the ironic position of Meyerhold and Golovin, post-revolutionary worker-artists still ensconced in the gilded cage of the formerly Imperial theatre.

To the critic N. Malkov, writing for “Teatr i iskusstvo" (Theatre and Art) magazine, the soloists seemed “like sepulchral wraiths".[52] Two sketches by N. Plevako[53] accompany Malkov's review. The amusingly gloomy faces of the singers depicted in the Plevako drawings may owe something to Malkov's bias, but these caricatures provide a valuable trace of Meyerhold's staging. Motionless on their benches, these former Imperial Russian performers seem to have little in common with the living, breathing nightingale, Andersen's symbol of the power of art, and much in common with his mechanical nightingale, a signifier of decadence and death.

For all the apparent simplicity of his devices, Meyerhold conjures a dizzying array of colliding concepts. The layered imagery at once asserts the fairy tale's imaginative illusionism and underscores its conventions: it questions the nature of character and identity; embodies a potent metaphor for the violently changing real world of civil war Russia just outside the theatre; and calls for life-giving art in the new state.

This splitting of characterization divided the audience. For the literal-minded, it was perplexing; in his review, the critic Malkov - disinclined to like anything about the production or the opera - fretfully lamented the disengagement of the singers from the physical action, remarking: “In Meyerhold's staging, the role of the fisherman is played by a singer on the forestage. The Fisherman sings of being charmed by a Nightingale - an unseen Nightingale, although, in Meyerhold's staging, the singer who plays her is seated directly before the audience."[54] Others were charmed; in a letter to the music critic Vladimir Derzhanovsky, Nikolai Myaskovsky (a modernist composer and fervent advocate of Stravinsky's music) wrote, “I liked ‘Nightingale' very much at the conceptual level: mime-concert opera. Those seated, singing Chinese were very nice, so much less falsehood than you get with performers singing and acting badly at the same time..."[55]

In Meyerhold's production, voice and body combine for the first time in Scene 3, in the person of the Little Cook Girl.[56] The Cook's appearance onstage, leading bumbling members of the court through the forest in search of the Nightingale, signals a transition from ethereality to farce. The Cook's elaborate headdress acknowledges her connection to the court, but her costume, linked via its blue colour to the Fisherman, sea, and sky, suggests her affinity with nature.

Into this natural world of Fisherman, Nightingale and Cook burst comical emissaries of the Emperor's court: the Chamberlain and the Bonze, accompanied by an entourage of courtiers (a male chorus consisting of four basses and four tenors). The spectacular quality of the production design is particularly visible in Golovin's renderings of the elaborate costumes for the courtiers. Although he had clearly researched Chinese costume and architecture, Golovin's design choices underscore his desired effect of satiric fairy-tale pastiche rather than historical or ethnographic accuracy. The courtiers' gaudily ornate dress marks the group as outsiders in nature, a status comically confirmed in the libretto by the Bonze and Chamberlain's inability to distinguish the lowing of a cow from the song of the nightingale. Yet once they hear the latter, guided by the Cook's discerning ears, they insist that the Nightingale accompany them to court to demonstrate his artistry for the Emperor.

Meyerhold's notes refer to Scene 3 as “the bridge entrance scene". That structure does not appear in any of Golovin's scenic renderings in the Private Collection, but does appear on the ground plan. As noted, there would have been at least a suggestion of a forest clearing setting in front of Golovin's seaside backdrop, and the bridge, which we know appeared later in the court scenes,[57] must have done double-duty here as the courtiers'[58] route into nature as well as their exit.[59]

Scene 4 continues as before. Meyerhold's notes call it an “Entr'acte (figuratively)": the “Fisherman's scene", a four-line solo preceding the actual entr'acte between Acts I and II.

The music of Acts II and III is strikingly different from that of Act I. For this reason Stravinsky, after a hiatus of five years, was initially reluctant to complete the opera: he recognized that Act I was written in a musical language he had already outgrown, and feared the subsequent two acts, created by the now-renowned composer of “Firebird", “Petrushka" and “Rite of Spring", would clash too strongly in style. He ultimately justified the disjunctive transition by noting the action's dramatic shift from magical forest to baroque court. The Golovin-Meyerhold production awkwardly inserted an intermission after Act I.[60] The break likely allowed for the complex set change from forest to palace, but may also have served to create an auditory distance between the contrasting musical styles. Nonetheless, the “rudetintinnabulation" of Act II's opening bars was an inside joke that the Mariinsky audience would have appreciated - Stravinsky was deliberately referencing childhood memories of St. Petersburg telephones ringing.[61]

Meyerhold's Scene 5 - “Breezes," the opera's actual entr'acte - consists of an orchestral transition to Act II.[62] The transition began behind a tulle curtain; to the music of Stravinsky's orchestral prelude, audiences saw: “Darkness; the first light of dawn". The chorus, singing “down front"[63], calls for torches and lanterns. Featured for the first time in Scene 5, the chorus was arrayed at the right and left of the proscenium. Meyerhold's notes and Golovin's design captions tell us that the chorus was composed of 12 performers of each vocal range, each group wearing an identical costume. The 1918 programme indicates an additional choral grouping not listed in Meyerhold's 1917 directing plan: a trio of “Voices of the People" (perhaps a savvy nod to the political times).[64] No such roles are identified in the libretto; these singers likely performed the brief solos for soprano, alto and tenor in the “Breezes" entr'acte.

In bustling shadow play behind the tulle, courtiers anxiously prepare for the appearance of the Nightingale. “Transparencies"[65] (electric lanterns built into the set and paper lanterns with candles carried by the performers) have been readied: the Little Cook, the Chamberlain and silent performers enter the stage, “marching in the procession bearing lights".[66] Despite his will to dislike the production, Malkov cannot help but describe the transition in terms that convey its charm: “Before a lowered tulle curtain, the orchestra plays the entr'acte to Act II... To the animated and lively music of this entr'acte, turmoil is taking place, depicting the reception of the Nightingale. The entr'acte turns into a Chinese march. The tulle curtain slowly rises."

It is Act II (Scene 6), and the lanterns gradually light up, revealing, in Meyerhold's words, “A fantastical porcelain palace. The fantasticality is [achieved] not only in the configuration of curved lines and intricacies of form, but also in the pattern of the transparencies (‘all the many lanterns')."[67]

The Act II stage was divided by a series of curtains. Down left, two “Chinese curtains" framed the scenic space, masking the top and sides of the proscenium: draped in textured, curving layers of varying length, and hung at a slight angle to one another. The downstage masking was composed of ornate fabrics hanging to several feet be low the proscenium; the upstage masking consisted, at stage left, of lacy patterns of birch and cherry branches, dipping down at an angle toward the stage floor. As the upstage masking extended right, it vanished behind the proscenium masking, re-emerging stage right as a swag of similarly ornate fabrics in a contrasting pattern.[68]

This angled placement achieved a poetic trick of perception: a play with frame and depth. The interplay between the pictorial and the three-dimensional mirrored the evocative oppositions in Meyerhold's blocking, in which the emphatically framed pictorial space upstage of the proscenium was aswirl with motion and life, the forestage dominated by a deathly stillness. This fracturing of the frame in both design and staging mirrors the tensions in Stravinsky's score, which veers from impressionistic “Mir isskustva" illusion to self-conscious modernist dissonance, from chromatic to pentatonic scale, teetering between worlds.[69]

On the mainstage stood just two structural elements: a bridge and a “Chinese Pavilion". The bridge had already been used in Act I for the courtiers' entrance to the forest. In Act II it was placed just upstage of the dripping lace of cherry and birch branches, emerging from stage left parallel to the forestage, half hidden by the proscenium wall. Curving gracefully upward, it was mounted at either side by flights of seven steps, and served as an entrance for the major characters - vaguely evocative of the hashigakari of the Noh stage, and perhaps serving a similarly allusive function: hinting at liminal space between realms, at dualities of imagination and actuality, theatre and life.

Centre right stood a Chinese Pavilion,[70] raised above stage level and mounted by two flights of steps. On Meyerhold's ground plan, the pavilion is denoted by a simple rectangle, though Golovin's set painting depicts this central pavilion room flanked by a panoply of architectural details - other rooms, ornate columns, steps, towers, and turrets - a rococo fantasia on the “Chinese manner", playing loosely, as in his costumes, with touches of Ming Dynasty elements.

Design details included a garden with flowers, a central motif of the Nightingale's three major arias. In the libretto, the dew on flowers is associated with tears, stars and diamonds, imagery repeated throughout the work, equating real emotion, real art, and real value with the beauty of the natural world. Golovin, a perfectionist of details (and himself an avid gardener), lavished special attention on the plants in the Emperor's garden. “I have a particular love of flowers," Golovin claimed, “and paint them with botanical precision."[71] In four detail renderings in the Private Collection, we see both the unadorned roses about which the Nightingale sings, and more fanciful flowers to which the nervous courtiers have tied silver bells to enhance their charm.

The Chinese Pavilion and Palace resemble multiple structures in the Alexander Park of Tsarskoye Selo, notably the Creaking Pavilion, the Great Caprice, and Catherine the Great's Chinese Village. The set's steeply arched bridge is reminiscent of the Cross Bridge, with its own chinoiserie pavilion, connecting the Catherine and Alexander Parks.[72] Meyerhold and Golovin may well have visited these spots during their meetings in Tsarskoye Selo in the autumn of 1917 - they are a short walk from where Golovin was then in residence in the gatehouse. Golovin's designs conjure that enchanted rococo atmosphere - as well as the more sombre echo of the deposed Romanovs, who only months before had been imprisoned there, on the grounds of their former palace.

As the tulle curtain rises and the palace is revealed, the Chinese March begins. In this four-minute musical passage, the libretto calls for the “solemn entry of the court dignitaries".[73] For Golovin and Meyerhold, it was an opportunity for spectacle. Golovin's painting of this scene, in a European private collection, gives a hint of its richness and dynamism,[74] with its mass of courtiers surrounding the Emperor and the palace.

This tempera on hardboard painting also includes an important change from Golovin's original set design - the addition of the arched bridge over which the procession took place. As noted, the bridge also appears on Meyerhold's ground plan, likely added to bring visual balance to the towering palace, to furnish another level and space for staging the large number of swirling performers, and perhaps to elevate some of the action above the heads of the chorus and the seated singers on the forestage.

Meyerhold and Golovin's scenic composition in Act II was striking for its asymmetry. Stage right and centre were dominated by the crowded Imperial world; stage left, by “negative space", evoking the natural world of forest groves, sea and sky. This asymmetry is replicated in Meyerhold's movement of the chorus from the forestage wings to a more central “on-stage" position. The chorus was divided into two groupings, at left and right, straddling the proscenium from the main stage into the forestage. Together, the Pavilion and the two choruses formed a triangle, extending unevenly down and across the broad Mariinsky stage, with the greatest weight of scenic architecture on stage right, and the furthermost downstage playing area spilling onto the forestage, left.

Of the performers appearing on the main stage, eight were singing principals, ranging from the Emperor (Pavel Kurzner)[75] and the Chamberlain (Aristide Belianin)[76] to the Little Cook (Yevgenia Talonkina).[77] A large contingent of silent performers also appeared on stage in Act II: a Court Footman “with a long pole atop which is the nightingale [puppet]", four sailors bearing the Emperor's throne, and six Ladies of the Court. This royal entourage was accompanied by 14 Chinese Boys armed with decorative props. The properties lists and some rapid pencil sketches among Golovin's designs at the St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music suggest tasselled parasols, ornamental crests on bamboo poles, lanterns, decorative platters laden with fruit, a pole with tiny bells, juggling knives - rich visual details creating a tapestry of colour, motion, sound and action. To this swirl of bodies and objects, Meyerhold added five musicians from the theatre's orchestra, bringing music into the onstage procession.[78]

Although Golovin made a single design for the livery of the extras (Golovin's caption and Meyerhold's directing plan indicate that there are 33 of them), each is individualized with different accessories; collectively, they are the silent, moving counterpart of the stationary but vocal chorus. The Private Collection includes a design for two children's costumes. They do not represent any identifiable characters in the libretto, but are clearly intended for the 14 boys of the Chinese court indicated in Meyerhold's directing plan.

At the conclusion of the Chinese March, four bearers carry on a canopied palanquin upon which is seated the Emperor of China. He gives the signal for the Nightingale to begin, and is moved to tears by his song. He offers the Nightingale the Order of the Golden Slipper in thanks, but the Nightingale - archetype of the selfless artist - replies that the Emperor's tears are reward enough. Despite the fact that “The Nightingale" is set in fairy-tale China, Golovin makes clear allusions to contemporary Russia in many of his designs. No citizen of Petrograd in 1918 would have had trouble equating the aloof, rococo figure of the opera's Emperor with the deposed Tsar. His costume bore a marked resemblance to the Tsar's own coronation vestments, an image known to virtually every Russian at the time.

Golovin produced two distinct costume designs for the Ladies of the Court. In a graphic demonstration of the court's inability to distinguish bad art from good, the ladies gargle with water from china cups in a vain attempt to imitate the Nightingale's beautiful warbling. The Chamberlain announces the arrival of three Japanese envoys, who come bearing a gift from their sovereign: a golden, mechanical nightingale. Golovin draws a sharp distinction between the silhouettes of these costumes and those of the Chinese court, portraying the Japanese through the eyes of their hosts, in a somewhat “barbaric" aspect (in view of Russia's humiliating defeat in their 1905 war with Japan, the Japanese characters might have had similarly negative connotations for the Petrograd audience).

The Third Japanese Ambassador carries the mechanical nightingale. In contrast to the real Nightingale, whose unassuming appearance cloaks enormous talent, the mechanical nightingale is a gaudy golden and bejewelled affair that can only regurgitate its wind-up tunes (played by the orchestra, another “doubling") until its gears go awry. During its “song", the real Nightingale flies off. The Emperor is so incensed that he banishes the bird from his empire, and names the Mechanical Nightingale first singer, to be installed on his left-hand royal bedside table.

In Scene 7, to a reprise of the Chinese March, the Emperor and the court withdraw as, one by one, the lanterns are extinguished. As the Fisherman sings his coda about the coming of Death, tulle curtains envelop the palace and storm clouds appear above. Scene 8 marks the start of Act III. As with each of the previous acts, the scene begins at night, and slowly transitions toward dawn. Within the raised Chinese Pavilion of the palace is inset the private bedchamber of the Emperor - a stage within a stage, reiterating the duality of the forestage and onstage worlds.

The Private Collection includes the detail design for this bedroom setting. It would have been unveiled in dim light approximating moonlight, pervaded by the haunted quality of Stravinsky's music. Golovin and Meyerhold, who often used cinematic language in their mise- en-scene, created a theatrical close-up with lighting.[79] Shrouded in gloom, the Emperor lies dying in his bed, his soul sick and his life ebbing with the loss of music after the breakdown of the Mechanical Nightingale. The Mime Death, a terrifying skeletal figure already wearing the Emperor's crown and bearing his sword of state and standard, sits at his bedside, the ruler's bleak double.

Though the Singing Death, like the Nightingale and Fisherman, was seated at a music stand, Plevako did not sketch soloist Antonina Panina, the mezzo-soprano who sang the alto role of Death.[80] Meyerhold's directing notes state that Death is “onstage", whereas the Nightingale and Fisherman are “down front". This suggests that the three soloists at their benches and music stands were triangulated, with Death centred slightly upstage of the Nightingale and the Fisherman, an interpretation supported by a triangle of three unlabelled squares down centre right on the ground plan, seeming to indicate placement of the soloists.[81]

Ghostly silhouettes and the Spectres of the Emperor's past deeds (sung by the alto chorus) haunt the Emperor and demand to be remembered. He attempts to drown them out by calling for music - at which the real Nightingale suddenly flies in and responds. Death is beguiled by the Nightingale's song, and in order to hear more, accedes to the Nightingale's request to return all he has taken from the Emperor. The Nightingale in turn sings his final “garden" aria, filled with images of Death's own garden - the graveyard. Moved by this song, Death disappears.

Dawn breaks. The Emperor feels his strength returning, and the Nightingale promises to come each night to sing to him again. In a sombre inversion of the earlier Chinese March, the courtiers and musicians, thinking the Emperor dead, advance to his bedchamber in a funeral procession, dressed in white robes (echoing, and perhaps parodying, the design of Death's own shroud).

They open the bed curtains, the palace is flooded with sunlight, and the Emperor welcomes them in full regalia. And “the thunderstruck courtiers fall prostrate, scattered about with their legs grotesquely in the air." The description is Malkov's; the image, a quintessentially Meyerholdian grotesque, juxtaposes the redemptive and the farcical.

During the Nightingale's final aria, the curtains of the royal bedchamber are lowered - “as if a gust of predawn wind made them drop [down] on their own," according to Meyerhold's lighting notes, and “the sun en- goldens the foreground."[82] The opera comes full circle, with the sun again rising and the voice of the Fisherman heard as at the opening, singing the final coda as the curtain descends.

Conclusion

In contrast with the Benois-Sanin staging of “Le Rossignol" in Paris, in which all singers - soloists and chorus - were costumed identically and grouped together in two large formations at either side of the stage, why did Meyerhold separate and give primacy of placement to the soloists in his production? And why did he choose in particular to spotlight the Fisherman, the Nightingale and Death by setting them on the forestage? The Fisherman, despite his prominent and recurring aria, is scarcely a part of the action in the first act and subsequently disappears except as a gentle offstage coda.[83] Death appears only in Act III and sings a mere two lines. Only the Nightingale has a leading role. So why was this particular trio of characters given prominence?

Meyerhold's notes do not explain his choice. But it is telling that this trio are outsiders in the world of Imperial power, representatives of the natural world that stands in marked contrast to the artificiality of the court. The Emperor and his leading retainers only exist within the frame of the proscenium. The Fisherman, the Nightingale and Death all transcend the physical limits of the stage, doubled by bodies that participate in the onstage action while the artists who give all three voice are placed front and centre. The voices are all beautifully costumed as if to convey - within the complex evocations of Meyerhold's poetics - the inward nobility and grace of characters whose outward appearance is either humble or threatening: a truly Andersen touch.

Even the chorus, relegated to the background in traditional opera, is placed prominently near the forestage, and complemented by physical doubles taking active, even acrobatic, part in the onstage action. By placing soloists, chorus, and of course orchestra outside the proscenium frame, Meyerhold privileges music and voice as opera traditionally has done. And yet he subverts the operatic process by inverting its physical presentation: musical/vocal operations are distinct from the “drama", what was traditionally background is now front and centre, and the royal figures who once reigned over the Mariinsky's auditorium from the Imperial box have now been placed onstage, within the opposing box of the proscenium.

The Fisherman, Nightingale and Death are also the characters who represent the intersection of spirit and flesh, of transcendent, abstract ideas and their embodiment. And they are iconic, an archetypal triumvirate representative of immediately recognizable fairy-tale “types", and vaguely evocative of the eternal triangle of modernist commedia: Pierrot, Columbine and Harlequin.

The satirical treatment of the Emperor's court in Stravinsky and Mitusov's libretto is true to Andersen's original tale. Meyerhold's production of “Solovei" heightened the elements of slapstick and grotesquerie, an approach that would resonate throughout his postrevolutionary work, especially in his treatment of Imperial power. In his 1923 production of Sergei Tretyakov's “Earth Rampant", for example, the Emperor urinates to the musical accompaniment of “God Save the Tsar", and his lackey carries the Imperial chamber pot out through the auditorium while holding his nose.[84] Meyerhold contrasts that irreverent vulgarity with the genuinely tragic notes in the death of the hero, much as he follows the unnerving near-death of the Emperor in “Solovei" with a buffonade resurrection.

Both the Benois and Meyerhold productions relied heavily on a proto-Brechtian distancing technique, addressing the disappearing culture of Tsarist Russia through the triple prism of fairytale, orientalist othering, and imagined historical past. But where Benois is elegiac, celebrating and mourning the passing of Imperial culture, Meyerhold is an ironist, arguably an early postmodernist, juxtaposing and rupturing and equivocating.

And it is perhaps this which most got under the skin of the crowd on “Solovei’”s opening/closing night, at least as much as the dissonant strains of Stravinsky's melodies. Meyerhold and Golovin's vision, it seems, rubbed the audience's nerves - already taut from a civil war that had reached the streets of Petrograd, from a monarch and his royal family under house arrest, from years of death and deprivation - equally raw. “We are simply in the wrong frame of mind," concluded Malkov in 1918, delivering a verdict which largely has stood until now, “to comprehend ‘The Nightingale' correctly."[85]

The authors extend their deepest thanks to Douglas Engmann and the Engmann Family for their tremendous generosity, support and patience throughout our years of work on this project. it truly would not have been possible without them.

Copyright © 2019 Brad Rosenstein and Kathryn Mederos Syssoyeva

- The year of the Mariinsky production is sometimes erroneously given as 1919, but there is a wealth of documentation substantiating 1918 as being the correct year. The opera had its world premiere with the “Ballets Russes” in Paris in 1914. Due to its French premiere, “The Nightingale” is typically referred to in publications by its French title. To distinguish between the two productions, we will refer to Stravinsky’s composition and its Paris premiere by the French title, “Le Rossignol”, and the Meyerhold-Golovin production by its Russian title, “Solovei”.

- Golovin had moved to Tsarskoye Selo, 24 kilometers southwest of St. Petersburg, in 1910 on the advice of his physician. In response to Golovin’s developing heart trouble, his doctor recommended both the quality of the air in Tsarskoye Selo and the distance it would allow him from “the daily anxieties of theatre life”. As Golovin notes in his memoir: “The air of Tsarskoye Selo was truly celebrated, but insofar as shielding me from theatrical anxieties, nothing came of that: daily anxieties only intensify when you’re far from your post.” Golovin, A.Ya. “Encounters and Impressions”. Ed. Gollerbakh, E.F. Leningrad-Moscow, Iskusstvo, 1940. P. 106.

- Malkov, N. ‘Igor Stravinsky’s “Solovei”.’//”Teatr i iskusstvo” (Theatre and Art) magazine. 1918, No. 20-21. P. 213.

- Taruskin, Richard. “Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works through ‘Mavra’”. Vol. II. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1996. P. 1090. Hereinafter - Taruskin.

- Benois, Alexandre. “Reminiscences of the Russian Ballet”. Trans. Britneva, Mary. London, Putnam, 1941. P. 359. Hereinafter - Benois.

- Taruskin. Pp. 1087-88.

- Credit for the bold staging concept would also be claimed by Michel (Mikhail) Fokine, director and choreographer of “Le Coq d’Or” (Fokine, Michel. “Fokine: Memoirs of a Ballet Master”. Trans. Fokine, Vitale; ed. Chujoy, Anatole. London, Constable & Company Limited, 1961. P. 226.), and even by Diaghilev himself, staunchly defended by the production’s designer, Natalia Goncharova. (Scheijen, Sjeng. “Diaghilev: A Life”. Trans. Hedley-Prole, Jane and Leinbach, S.J. Oxford, et al.: Oxford University Press, 2009. P. 290, n. 46, p. 487.) See below for the influence of Meyerhold’s stagings on the “Ballets Russes”.

- Benois. P. 354.

- Taruskin. P. 1072, n. 64.

- Ibid. P. 1087.

- The opera’s strong advocates at the Mariinsky were the intendant of the Imperial Theatres, Alexander Siloti, an early champion of Stravinsky, and Albert Coates, who would conduct the 1918 production.

- The premiere of “Solovei” at the very end of the 1917-18 season seems to have been intended merely as an introduction. (A gossipy review by “Nekto” (see below) suggests that the hurried mounting after nearly four years of delay was primarily to prevent a fine: repertory theatres that did not fulfil their announced seasonal programming obligations were required to pay a penalty. Both Nekto and the reviewer Malkov indicate that they expected to see the opera again the following season.) Meyerhold’s notes from administrative planning meetings (SGO) regarding the 1918-19 season also clearly indicate that “Solovei” was to remain in the repertoire: Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (RGALI) Fund No. 988, Series 1, Filing Unit Nos. 799.19 and 799.29 (the latter dated May 18 1918: the meeting took place in Chaliapin’s apartment) both show “Solovei” actively discussed for the next season, and subsequent to its premiere it appears on a list of the 1918-19 season repertoire at the Mariinsky (RGALI 988-1-799.30, dated July 22 1918). It is likely that the director would have refined the production for subsequent performances, and that its disappearance from the Mariinsky’s stage perhaps had less to do with its “failure” than with Meyerhold’s departure soon afterwards for Moscow.

- The Golovin designs for “Solovei” were seen in Meyerhold’s Petrograd study in late February 1918 by the American visitor Oliver Sayler, who was in Russia during the tumultuous winter of 1917-18 to learn about its theatre. Sayler met both Golovin and Meyerhold, although he left the country before “Solovei”’s premiere. (Sayler, Oliver M. “The Russian Theatre Under the Revolution”. Boston, Little, Brown, and Company, 1920. P. 206.) A few of the designs also make a tantalizing appearance in the Russian emigre journal “Zhar Ptitsa” in 1923 (No. 10. Pp. 15-18) published in Berlin and Paris, before disappearing from view for over six decades.

- In Golovin’s memoirs, he states that “Solovei” was largely staged by his associate Pavel Kurzner (who also sang the Emperor) because Meyerhold was busy with other projects. But cast member George Balanchine’s recollections suggest Meyerhold’s powerful presence at rehearsals. (Volkov, Solomon, “Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky: Interviews with George Balanchine”. Trans. Bouis, Antonina W. New York, Simon and Schuster, 1985. Pp. 164-66. Hereinafter - Volkov.) And in any case, Meyerhold’s detailed directorial conceptions in his notes and plans seem to have been executed quite faithfully in the final production.

- Meyerhold was assassinated as an “enemy of the state” in the Lubyanka prison in Moscow in 1940.

- The original Golovin designs were rediscovered in the collection of Masha, Douglas and Michael Engmann of San Francisco, the family of Michael Klatchko, a Russian doctor with family ties to Leon Bakst. They are now in a Russian private collection. Hereinafter referred to as the Private Collection, it consists of original watercolour renderings by Golovin including four scenic designs, 22 costume designs and four scenic details - a nearly complete record of the entire production. All are signed or monogrammed and include captions and design details in Golovin’s hand. “The Nightingale” designs in the collection of the St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music consist of 16 costume designs (assumed to be copies made by Golovin’s assistants) that are unsigned and largely uncaptioned, an original prop rendering for the Mechanical Nightingale (captioned and monogrammed by Golovin), and several pages of preliminary pencil sketches. We also know of three additional renderings in other private collections. All references to visual details of the costume and set designs are to the Private Collection renderings unless otherwise noted. The complete Engmann Collection was also exhibited at Bonhams in London, 24 May-6 June 2018, to mark the centenary of the 1918 production. “Music, Magic and Flight: Alexander Golovin’s Designs for the Lost Production of Igor Stravinsky’s ‘Le Rossignol’” was curated by Brad Rosenstein and Yelena Harbick.

- In 1988, Nancy Van Norman Baer included several of the Golovin designs from the Engmann Collection in her exhibition “The Art of Enchantment: Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 1909-1929” (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, 3 December 1988-26 February 1989). Although correctly citing them as being by Golovin for a production at the Mariinsky, she misidentified them as designs for “Le Chant du Rossignol, 1919”, conflating them by title with the 1920 ballet designed for Diaghilev’s company by Henri Matisse, rather than the original opera, and misstating the year. She also claimed that the Mariinsky production was “directed by Konstantin Stanislavsky”, rather than Meyerhold. (Baer, Nancy Van Norman (ed.). “The Art of Enchantment: Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 1909-1929”, San Francisco/New York: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco/Universe Publishing, 1989. Pp. 75-76, 86.)

- The most extensive and accurate account of the opera’s creation and premiere is in Taruskin, especially pp. 1068-1108. See also generally Walsh, Stephen. “Stravinsky: A Creative Spring - Russia and France, 1882-1934”. New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.

- This article draws upon analysis of the rediscovered designs, in combination with extensive archival research, conducted in Moscow at the Bakhrushin Theatre Museum, Lenin Library, and RGALI archives, and in St. Petersburg, at the State Library, the Mariinksy Theatre Archives, and the St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music. It is further supported with research conducted in the U.S. (at the theatre archives of Harvard University and The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts), Australia (The National Library) and France (the Bibliotheque Nationale). We draw upon primary source materials that include Meyerhold’s production notes, blocking designs, and ground plans, Golovin’s preliminary sketches, correspondence between Stravinksy, Benois, Meyerhold, Golovin and Siloti, and eyewitness accounts and reviews.

- Braun, Edward (ed. and trans.). “Meyerhold On Theatre”. New York, Hill and Wang, 1969. P. 75.

- “Peterburgskaya gazeta” (St. Petersburg Newspaper). St. Petersburg, 24 April 1908. Quoted in Braun, p. 75.

- There are several key errors of dates in Golovin’s chronology. The artist himself may have been the source of some of these errors (such as the 1919 date for “Solovei”), which seem to originate in his memoirs (or in the 1928 biography based on Golovin’s memories recorded by Erich Gollerbakh) and subsequently repeated throughout the literature. Golovin dates the start of his work with the Imperial Theatres in Moscow as 1898, but the correct year is actually 1900. Kruglov, Vladimir. “Alexander Golovin 1863-1930”. Trans. Blasing, Keith. St. Petersburg, Palace Editions and the Russian Museum, 2013. Pp. 14-15, n. 10. Hereinafter - Kruglov.

- The summary of Golovin’s early career here and in the next three paragraphs is largely adapted from Kruglov. Pp. 5-8.

- Benois, Alexandre. “The History of Russian Painting in the 19th Century”. St. Petersburg, 1902. P. 257. Quoted in Kruglov. P. 6.

- Kruglov. P. 8.

- Hoover, Marjorie L. “Meyerhold and His Set Designers”. New York, American University Studies XX/3, Peter Lang, 1988. P. 62.

- Rudnitsky, Konstantin. “Meyerhold”. Moscow, Iskusstvo, 1981. P. 150. In Ibid, p. 53.

- Op. cit. P. 53.

- Meyerhold, Vsevolod. “Tristan and Isolde”, initially a lecture delivered in November 1909. First published in “Yezhegodnik Imperatorskih teatrov” (Yearbook of the Imperial Theatres),

- St. Petersburg, 1910, no. 5. Reprinted in Meyerhold’s “About Theatre”, 1913. Pp. 56-80. In Braun, pp. 80-98.

- Braun. Pp. 80-81. Italics Meyerhold’s.

- Maeterlinck referred to “Sister Beatrice” not as a play but as a “miracle in three acts”. In fact, it was an opera libretto that had yet to find its score - perfect material for Meyerhold at this juncture.

- Ibid. P. 82. Italics Meyerhold’s.

- Groundplan 2 (outcome of a design meeting between Meyerhold and Golovin in Tsarskoye Selo on November 19 1917).

- Given “The Nightingale”’s brief running time, the evening’s programme for the Petrograd production was rounded out by “Jota Aragonesa”, an acclaimed 1916 ballet devised by Fokine and Meyerhold, designed by Golovin. (Opening night playbills for “Solovei” at the Mariinsky Theatre, May 30 1918. St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music).

- Syssoyeva, Kathryn Mederos. “Meyerhold and Stanislavsky on Povarskaya Street: Art, Money, Politics, and the Birth of Laboratory Theatre”. Dissertation.

- Stravinsky, Igor; Mitusov, Stepan. Russian text after Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale, English adaptation by Robert Craft. “Solovei/Le Rossignol/The Nightingale”. Opera in three acts. New York, Boosey & Hawkes, 1956. All summaries of and quotations from the libretto are based on this source unless otherwise noted. Hereinafter - Craft.

- Pozemkovsky, Georgy Mikhailovich (1892-1958), lyric tenor.

- Volevach, Neonila Grigorievna (1891-1980). Coloratura, soloist with the Mariinsky Theatre from 1914 to 1919. Performer names here and following are from the notes of research assistant Julia Kleiman, from “Theatre Review” and the archives of the Mariinsky Theatre.

- The doubling and staging are outlined in the Directing Plan and in Meyerhold’s various drafts of the opera’s Dramatis Personae, which he seems to have evolved in two meetings with Golovin in Tsarskoye Selo on September 18 1917 and November 19 1917. RGALI No. 998, Series 3, Filing Unit No. 1. Other details are drawn from Golovin’s designs and the reviews by Malkov (cited above) and “Nekto” (a nom de plume, literally “Somebody”). “Solovei”, Theatre Review, 6 June 1918, No. 3755.

- “Solovei” opening night playbills, St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music.

- Kendall, Elizabeth. “Balanchine and the Lost Muse”. New York, Oxford University Press, 2013. Pp. 118-119. Kendall also notes Balanchine’s experiences as a Theatre School student playing various minor roles in Meyerhold productions.

- Dramatis Personae. RGALI 998.3.1.

- The post-revolutionary leadership of the State Theatres, in attempting to make the arts accessible to a broad proletarian public, from early 1918 on began to offer inexpensive performances to a wide range of audiences. The Mariinsky seems to have pursued an especially close relationship with the naval base at Kronstadt, with “the opera troupe performing... once a week at the sailors’ club there”. (Frame, Murray. “The St. Petersburg Imperial Theaters: Stage and State in Revolutionary Russia, 1900-1920”. Jefferson, North Carolina and London, McFarland & Co., Inc., Publishers, 2000. P. 171.) Throughout his directing plan, Meyerhold includes “4 sailors” among his projected cast, specifically assigning them to carry in the throne bearing the Emperor in the Act II procession. In that time of extreme privation, the priority-rationed sailors would have been among the few strong enough to carry out the task. And including them in onstage roles would have sent a positive political message as well. This gesture was perhaps also something of a palliative for the near-riot caused by the non-repeated “sailor” number at the “Solovei” dress rehearsal presented the day before (‘Stormy Scenes in the Mariinsky Theatre’//“Novaya Petrogradskaya Gazeta” (New Petrograd Newspaper), No. 108, May 30 (17), 1918. RGALI F 998, Op. 1, ex. 133.

- Stravinsky’s opera runs approximately 45 minutes, but its three scenes are referred to as Acts in the libretto.

- RGALI 998, Filing Unit No. 1, 134, 14 (Mise en Scene). Meyerhold’s remarks regarding “au vista’’ changes are minimal: his act and scene breakdown appears under the header, “on sets and their au vista changes”.

- Craft. P. 11.

- «Бледен, бледен серп луны. Слышу тиxий плеск волны.» Translator's note: passages from the libretto cited in the original document correspond to the English version of “The Nightingale” libretto by Robert Craft. As there are variations between the Russian and the English versions of the libretto, the Russian passages are also provided here for reference.

- All lighting remarks are from Meyerhold’s notes “On lighting effects”, Mise-en-Scene, p. 13, November 23 1917.

- See, generally, Posner, Dassia N. “The Director’s Prism: E.T.A. Hoffman and the Russian Theatrical Avant-Garde”. Northwestern UP, 2016.

- The music stands and wooden benches are documented in the sketches by N. Plevako (see below), and are mentioned in both the Malkov and “Nekto" reviews, and in Rudnitsky, Konstantin. “Meyerhold”. Moscow, Iskusstvo, 1981. P. 233. Balanchine also recalled the benches (Volkov. Pp. 165-166).

- This egalitarian motif extended to the printed programme, where only the artists’ surnames were listed, preceded by the titles “Citizen” and “Citizeness”. Op. cit., “Solevei” playbills, St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music.

- Malkov’s review, though negative, provides the most detailed eyewitness description of the performance.

- Reprinted in Rudnitsky, Konstantin, “The Director Meyerhold”. Moscow, Nauka, 1969.

- Ibid.

- Vladimir Derzhanovsky, editor of the journal “Music”, and Nikolai Myaskovsky (1881-1950), a Russian and Soviet modernist composer who collaborated with Prokofiev while students together, taught in St. Petersburg, and is considered by Taruskin to have been one of Stravinsky’s most sensitive and insightful advocates.

- This accords with the opera’s published score, which specifies that the Fisherman and the Nightingale are both first heard as disembodied voices from the orchestra pit. Stravinsky, Igor. “Le Rossignol/The Nightingale”. Conte lyrique en trois actes de I. Stravinsky et S. Litousoffd'apres Andersen. (Piano score). Traduction frangais de M.D. Calvocoressi. English translation by Robert Craft. Edition Russe de Musique (S. & N. Koussewitzky)-Boosey & Hawkes, 1956. (“Upstage, the Fisherman in his boat [7]...The singer is in the orchestra pit; on the stage an actor mimes the Fisherman’s role.”[8] “NIGHTINGALE (Voice from the Orchestra)” [18].

- See below for description of rendering in another private collection.

- The Courtiers perform on stage, apart from the forestage Chorus. Dramatis Personae, 1.

- As per libretto. Meyerhold’s notes give no indication of these exits.

- “Solovei” playbills, St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music.

- Stravinsky, Igor and Craft, Robert. “Expositions and Developments”. London, Faber Music Ltd., 1981, reissue of 1962 Faber & Faber edition. P. 30.

- Corresponds to Libretto, “Scene II”. Pp. 16-18.

- The note on chorus placement - on the lower right-hand side of the page, circled - appears to have been added later. (RGA- LI, Fund 998, Filing Unit No. 1, 134, 2 (Dramatis Personae). It is unclear whether “down front” indicates before or behind the tulle.

- This role, with the singers’ names that follow, comes from a list of “Solovei” performers compiled by researcher Julia Kleiman. “Voices of the People (Голоса из народа)” does not appear in the list of Dramatis Personae from Meyerhold’s notes, but does appear on the programme. Ivanova (Иванова); Leonova (Леонова); Ozhelsky (Олжельский).

- Meyerhold uses the term “transparencies” to refer to the many large and small lanterns appearing in the production. See his notes for Scene 6 in “In sets and their au vista changes” and “On lighting effects”. Golovin’s tempera painting of the procession scene (referenced below, in a European private collection) gives a sense of how prominent the lanterns became in the final staging.

- Meyerhold’s notes are unclear about the number of silent performers in this procession; elsewhere, however, he notes that the number of lanterns is 17.

- Corresponds to libretto, end of p. 18.

- Meyerhold and Golovin’s notes, as indicated on the ground plan (presumably issued by Golovin’s design team) and the blocking plan (in Meyerhold’s hand) are somewhat at odds; the design team labels the forestage masking “Chinese Curtain”; Meyerhold labels the upstage, angled masking “Chinese Curtain.” At a glance, the scene paintings do little to solve the mystery due to Golovin’s style, for whom depth is subsumed into a flat play of contrasting patterns. Lines for both sets of masking appear on each of these documents, however, and with careful study, the contrasting patterns on the stage left and right sides of Golovin’s paintings begin to distinguish themselves into a suggestion of layering and depth.

- See Taruskin, pp. 1091-1106, for a musicological analysis of the opera.

- Meyerhold uses a Russian term for summerhouse or gazebo, беседка; the drawings suggest an ancient Chinese architectural style of structure for which “pavilion” is a more accurate term.

- Golovin. P. 97.

- See photographs in Popova, Natalia and Raskin, Abram. “Tsarskoye Selo: Palaces and Parks”. Trans. Fateyev, Valery.

- St. Petersburg, Ivan Fyodorov Art Publishing, 2003. Pp. 89-91.

- Craft. P. 19.

- Alexander Golovin (1863-1930). Stage design for the opera “The Nightingale” (1918). Tempera on wood. 71.5 * 102 cm. Private collection. Exhibited in “Russes”, Musee de Montmartre, Paris, 20 June-21 September 2003. Exhibition catalogue, illus., p. 102. Such paintings seem to have been a feature of Golovin’s design process - they exist for a number of his productions. Whereas his initial set designs (typically watercolour on paper) are usually devoid of human figures other than to indicate scale, these paintings (often roughly executed in tempera on board) later in the process show both modifications to the set design and include figures to indicate the staging. Interestingly, the painting does not include the chorus or soloists on the forestage.

- Kurzner, Pavel Yakovlevich (1884-1950): bass; opera singer, later dramatic actor and music-hall performer (J. Kleiman).

- Belianin, Alexander Vasilievich (stage name: Aristide, 18741943), basso profundo. Belianin had sung the same role in the 1914 Paris premiere: he was the only performer to appear in both productions.

- Talonkina, Yevgenia Ivanovna (1892-?), soprano.

- Dramatis Personae, 2. Also see note on Planirovka: “Question for Coates which instruments for orchestra on the stage?”

- Meyerhold directed his only two films in this period: “The Picture of Dorian Gray” (1915) and “The Strong Man” (1917). (Leach, Robert. “Vsevelod Meyerhold”. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989. P. 13.) “The Picture of Dorian Gray”, Oscar Wilde’s classic tale of “doubling” and the split between body and soul (life and art) received further Meyerholdian twists of identity by casting a woman (Varvara Yanova) as Dorian and the director himself as Lord Henry Wotton. Both films are considered lost.

- No costume is specified for Panina in the directing plan, and no design for her costume exists in either the Private or St. Petersburg Museum of Theatre and Music collections. Given the extreme brevity of her role, it is possible that Panina was costumed similarly to the alto chorus. And so in keeping with the strong visual contrast between the Mime and Singing Fisherman, as well as that between the Singing Nightingale and her modestly described puppet counterpart, it is likely that the singer voicing Death was elegant, in striking contrast to the grim spectre of the mute onstage Death.

- In the playbill, however, the singing Death, like the singing Fisherman and Nightingale, is listed as being “on the forestage”.

- Meyerhold, “On lighting effects,” Mise-en-Scene, 13, op. cit.

- At least as indicated in the libretto. It is unclear whether Meyerhold brought the Mime Fisherman back onstage for these later arias, or left them to the Singing Fisherman.

- Leach. P. 133.

- Malkov. P. 213

See also:

-

Natalya Makerova. Meyerhold and Golovin

Magazine issue: #3 2014 (44)

Italian pencil on paper. 31.5 × 22 cm

© Russian Museum

Gouache, watercolour, gold, silver, graphite pencil on cardboard. 48 × 62 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Tempera, pastel on canvas. 136 × 143 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Watercolour, ink, lead pencil, silver paint on paper. 47.3 × 23 cm

© Russian Museum

Silver paint, brush, ink, lead pencil, white paint, watercolour on paper. 33.4 × 20.3 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Gouache on paper on cardboard. 78 × 70.3 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Gouache on paper glued to cardboard. 107 × 85.2 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Gouache, white and watercolour on cardboard. 37.5 × 51 cm

© Russian Museum

Watercolour, pencil on cardboard. 32.1 × 24.1 cm

© Bakhrushin Theatre Museum, Moscow

Pencil, watercolour, ink, pen, bronze on paper. 34.5 × 30.9 cm

© Bakhrushin Theatre Museum, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 161 × 116 cm

© Russian Museum

Gouache, silver and bronze paint, ink, reed pen on cardboard. 71.2 × 102.2 cm

© Bakhrushin Theatre Museum, Moscow

Tempera on canvas. 77 × 99.5 cm

© Russian Museum

Watercolour, gouache, bronze and silver paint, pastel on cardboard. 66.5 × 81.5 cm (without frame)

© Bakhrushin Theatre Museum, Moscow

Watercolour on paper. 63.9 × 90.4 cm (without frame)

© Bakhrushin Theatre Museum, Moscow

Majolica. 60.7 × 52 × 7.7 cm

© Abramtsevo Historical-Artistic and Literary Museum

Photograph by Brad Rosenstein

Watercolour and gouache on paper. 53.5 × 83.3 cm

Private collection. © Sam Sargent Photography

Coloratura, soloist with the Mariinsky Theatre from 1914 to 1919, she sang the role of the Nightingale in the 1918 production. Photograph by D. Bystrov, 1919