"Living in the territory of art”. NEW PERSPECTIVES ON MIKHAIL LARIONOV

Something of a legend in Russian art of the early 20th century, and one of the most brilliant representatives of the country’s avant-garde of that time, Mikhail Larionov is one of the last artists of his generation whose work can be said to have “returned” to Russia in its entirety. His exhibition history has been complicated: a participant in, and organizer of some of the “roaringly popular” shows of the 1910s, Larionov left Russia on Diaghilev’s invitation in 1915, and his name has somehow been “missing” from the country’s cultural map ever since. World War I, the Russian Revolution and the Civil War made it practically impossible for the artist, then living in France, to participate in the artistic life of his homeland. Thus, the new exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val that opened in September 2018 reveals many new facets of Larionov’s work to Russian viewers.

In the late 1920s, the collection of Larionov's paintings and drawings that had been kept for him in Moscow by the architect and collector Nikolai Vinogradov was sent on to the artist in Paris. Before it was finally dispatched, the Tretyakov Gallery acquired several of the artist's compositions to add to those pieces that it received at around the same time from the reorganizations of the Museum of Visual Culture, which until then had been a repository of the Russian avant-garde, and the Museum of New Western Art.[1] However, as a result of the changing ideological priorities of Soviet culture over the decades, works by Larionov and his fellow artists of the avant-garde were for many years confined to storage by the museums that owned them, inaccessible even to researchers.

It was only in 1979, thanks to the determined efforts of the artist's second wife, Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, that the Russian Museum and Tretyakov Gallery organized an exhibition which for the first time featured Larionov's works from both Russian and French collections and museums in the same space; that show did not present by any means all of Larionov's art, however, and regrettably its catalogue, although prepared, was never published. Finally, in 1989, the dream of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova came true, and their legacy returned home: the Tretyakov Gallery received the artists' paintings and drawings, as well as their vast archive and library. In 1999, in accordance with the will of Larionov's widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, the Tretyakov Gallery organized two exhibitions, of oil paintings and graphic works, drawn from that donation.[2] The 2018 exhibition, bringing together as it does the artist's signature works from museums and private collections in Russia and abroad, is effectively Larionov's first major retrospective in Russia.

Its curators faced a particular challenge, how to present Larionov's legacy in a way that captured his artistic individuality: while Larionov is a very good artist indeed, he was also a very prolific one, who practically never stopped working. His oeuvre runs to some tens of thousands of works, and he applied his creative genius in very different, sometimes quite unexpected forms. The intention in the new show was not only to showcase Larionov's best works but also to introduce viewers to his dazzling creative personality, to show him as someone “living in the territory of art".

Thus, large groups of his works have been omitted, including Larionov's pastel pieces, although pastel was the dominant technique that the artist used at the beginning of his career: it was just such works that first attracted the attention of his early collectors. In 1904, the doctor-collector Ivan Troyanovsky bought 10 pastel pieces from a show of student works at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, while the pastel “A Garden in Spring" (1905, Tretyakov Gallery) was one of the first items acquired by Ivan Morozov for his collection. There were other criteria in the selection process, too: regrettably it proved impossible to bring pieces from American museums to Russia, so such items appear only in the exhibition's catalogue. But the show features a number of major paintings from Russian and European museums, and brings together works from the Tretyakov Gallery and the Centre Georges Pompidou, including the renowned series “Seasons" (1912).[3] The Tretyakov Gallery owns a large and varied collection of Larionov, but this new exhibition is enhanced by a number of works from private collections, which include some of the artist's best pieces.

The show is divided into several major sections, covering respectively the artist's Russian period, his work in theatre, his French period, and the Larionov collection. The Russian section showcases painting, which was undoubtedly central to his oeuvre at that period: drawings were a working tool, useful for continuous training of the hand as well as the eye, for developing the skill of capturing all things distinctive and expressive that the artist found in his world. By contrast, the French section features mostly graphics - drawings and gouache pieces, which were the focus of Larionov's creativity in his Paris years.

His Russian period opens with the artist's earliest pieces, created in the late 1890s-early 1900s - the “Larionov before Larionov" period - which comprise something of an introduction. In search of a distinctive identity, Larionov was sensitive to new impressions. His “gallant pieces" (“A Gallant Scene", “A Lady and a Cavalier", “Ladies with Umbrellas", all produced in the late 1890s-early 1900s, now at the Tretyakov Gallery) are indicative not so much of “18th century French influences"[4] as of his reaction to the “World of Art" shows; it is no coincidence that in Eli Eganbyuri's 1913 catalogue they are dated to 1898, the year of the first “World of Art" exhibition. The theatre-themed compositions, such as the series “In the Wings", reflect not only the artist's interest in theatre and his work as a stage-designer but also the work of Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, which Larionov might well have seen in the Shchukin and Morozov collections.

Nevertheless even in these “replicas" Larionov's originality is becoming evident: the compositions a la Benois have a grotesquery to them, while his “Lautrecian" images are enriched with impressions gained from provincial Tiraspol. Such “gallant pieces" are featured next to the silvery wet-on-wet painted winter landscapes, which betray the influence of his teachers Valentin Serov and Konstantin Korovin. These small-scale pieces and sketches in which a thick mass of colour either swirls like a snowstorm, or drifts like the stream of the rivers featured in their landscapes, demonstrate an easy command of the artistic techniques that Larionov had acquired in his early years at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture.

The second part, “A Tiraspol Garden", features the artwork he produced in 1905-1907 and is dedicated to Larionov the Impressionist.[5] This was an early stage in his rise to fame, the period when the artist was actively exhibiting with the Society of Moscow Artists, the Union of Russian Artists and the “World of Art" association, and when Moscow collectors were enthusiastically acquiring his artwork. Larionov's first triumph came in 1906, when Diaghilev invited him to participate in his “Exposition de l'art russe" in Paris, making the artist one of the few contemporary figures to feature in the “history of Russian art" that Diaghilev presented with such fanfare.[6] (It is no surprise that Larionov described this episode in his memoirs many times.) Larionov's Impressionism blossomed not only from these “French lessons" and his firsthand knowledge of the work of Van Gogh, Monet, Bonnard and others - it was also somehow “extracted" by the artist from the very light and air of the scenery of the South. These landscapes seem to preserve and accumulate the sensations of happiness that the artist experienced in the garden of his Tiraspol estate as he painted its apricot trees and rose bushes, blossoming apple boughs and crowns of acacias. His familiarity with French art “attuned his eyes", even as his grandmother's garden became something of a personal Giverny. Among the works from this time the Tretyakov exhibition presents “Garden" (mid-1900s, Russian Museum), which featured at the 1906 exhibition in Paris, “An Apple Tree After Rain" (1906, Tretyakov Gallery, originally from Ivan Morozov's collection) and the famous “Acacias" (1906, Russian Museum, originally acquired by Nikolai Ryabushinsky), which show that the most prominent collectors of the early 20th century had started to take notice of Larionov. It's worth pointing out that, unlike Morozov with his interest in French art and landscape painting in particular, Ryabushinsky set his sights on the artists of Symbolism. The fact that Viktor Borisov-Musatov was among the artists whom the young Larionov particularly revered is no coincidence: Borisov-Musatov helped Larionov to “see" and feel the delicate boundary between reality and dream, between the imagined and the experienced, and to notice almost imperceptible changes in the states of nature (“Blue Roses", “Dawn", both 1907, Tretyakov Gallery).

Many of the works on display have particular histories behind them. For example, “A Garden in Spring" (1906-1907, Museum of Fine Arts of the Republic of Tatarstan, Kazan) has returned to the Tretyakov Gallery for the duration of the exhibition after an absence of almost three quarters of a century. It had been purchased for the Gallery as early as 1907, from a show of the Union of Russian Artists: as the memoirs of the patron of the arts Andrei Shemshurin remind us, “when many of the artists were sweating away to gain themselves a place at the Tretyakov Gallery, Larionov was already there."[7] “A Garden in Spring" entered the Kazan museum collection in the 1930s.

-

A Garden in Spring. 1905

Pastel on cardboard. 42 × 48 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

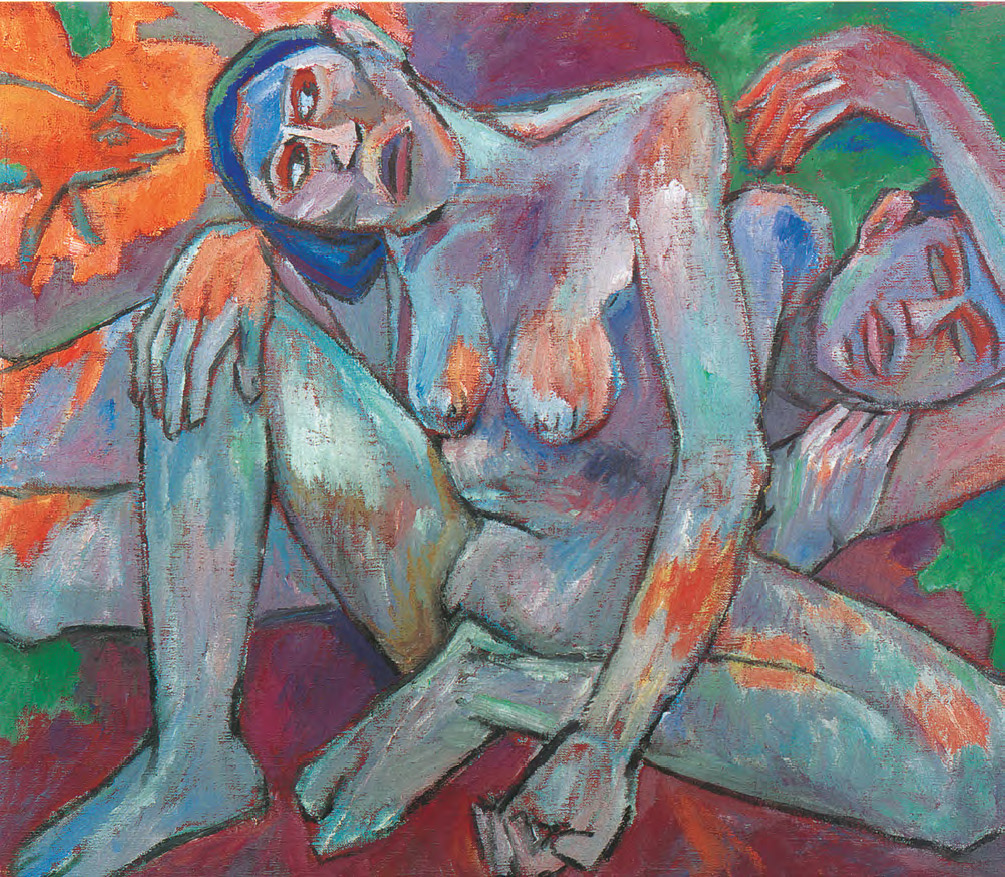

The next part of the show, tracing the further evolution of Larionov's Impressionism, might be titled “Animate Nature", and marks the period when the artist was working en plein air. The world of nature tempted him to leave the studio that he had set up for himself in an outbuilding at his Tiraspol home: quite naturally his pictures featuring the interiors of houses always include open windows. He painted his female models in gardens, amidst lush verdure, or at the seaside. But surprisingly, at the same time as he was working on several series of images of women bathing, he was also producing images of animals; these pieces feature geese, ducks, oxen and dogs, the denizens of farmyards who, on an equal footing with the places' human inhabitants, were such a fixture of everyday life in the provinces that they could claim a rightful place in art. Larionov's friend and biographer Sergei Romanovich recalled a striking episode during one of his visits to Larionov: “There were geese wandering about the yard, and the artist was watching them with a focused attention that I found astonishing."[8] The numerous charcoal sketches have the insightful perception of a naturalist and capture the animals' characteristic ways of movement, sometimes even a sense of their “character" itself. Only Larionov could take notice of the “colour of a nanny goat's eyes", as the inscription on one of his sketches reads.[9]

The drawings capture exactly such characteristic elements, which the artist then developed in his painted compositions, tracing figures with a fluid, animate red line. The luxurious plumage of turkey cocks or fish scales discarded on the ground turn into a veritable testing area for exploring the potential of brushwork. “Animate nature" is given unconditional priority - “not plein air, but living outdoors," was how Larionov himself put it in the 1920s.[10] Larionov's images of women bathing at different times of the day (1907-1908, Tretyakov Gallery; National Gallery of Armenia, Yerevan), “Fishes" (1908, Russian Museum) and “Peacocks" (1907-1908, Mashkov Fine Arts Museum, Volgograd) are arguably analogous to Claude Monet's celebrated series of images of Rouen Cathedral. Larionov was not “an analytically minded person", as Eganbyuri characterized him:[11] he was a poet keenly aware of changes in the natural environment in which he lived, of the very breathing of that “animate world".

-

Peasant Women Bathing. 1909

Oil on canvas. 89 × 109 cm. Kovalenko Regional Art Museum, Krasnodar

A similar sense of life penetrates even Larionov's “inanimate nature", as the section titled “In the Studio of a Russian Cezanne", featuring still-lifes produced in 1907-1909, reveals. The title is necessarily tentative: looking at the still-lifes with pears, that favourite theme of Cezanne, and identifying similarities and dissimilarities with the French master's works, one begins to understand that these pieces are indisputably by Larionov. The still-life is, in some sense, a very personal genre for any artist, who selects and arranges the objects to be painted - and that selection is in no way accidental. In his compositions Larionov engages in what might be called a dialogue with the French masters, sometimes even competing with them. Larionov depicts those “classic" Cezanne pears, while next to them, with palpable irony, he arranges a “provincial" composition, the head of a cabbage and crayfish crawling across the table. His still-lifes are always full of motion - there are tables “capsized" towards the viewer, odd fragments of stairs and chairs included in the compositions, crumpled napkins, the foliage of trees “accidentally captured" in the margins of a picture. Each of these items, whether flowers, fruit or vegetables, has a distinctive characteristic - one is even tempted to say a “distinctive character", a “personal" configuration. Larionov's still-lifes seem to demand a new generic term: neither “still life" nor “quiet life of objects" is appropriate.

The still-lifes of Natalia Goncharova from the late 1900s feature, alongside other objects, works of art, including some by Larionov. Larionov himself made use of such artistic citations only rarely, so when he did so it becomes a statement. The composition “Flowers on a Table" (1909, Russian Museum) is an image of a studio - it clearly evokes pieces by Matisse from the Morozov collection, such as “Fruits, Flowers, and the Panel ‘Dance'" (1909, Hermitage) - that includes an easel with Larionov's “Provincial Dandy" on it, an example of Russian national style held up to spite the French. By 1908-1909, Larionov was not only participating in, but also organizing major shows, including those of French art held at the “Golden Fleece" salon in Moscow: he felt that he was on an equal footing with the French artists. Perhaps this was the reason why at that period he created one of his first self-portraits - over his entire life Larionov painted only a handful of them - in which he depicted himself in his studio, with an unfinished statue visible in the background and a saw hanging on the wall.[12] This composition has something in common with Cezanne's self-portrait (1872, Hermitage, formerly from the Morozov collection), where the artist is depicted in a casquette, as a worker. Larionov, too, accentuated his essence as a working man, evidence of his kinship with those artisans whose works he not only collected but also exhibited alongside his own compositions.

The title of the next part, “Russian Tahiti", comes from Goncharova. She wrote: “Larionov is from the South: there, the white sweet-smelling acacias are in full bloom, the houses are yellow, rosy, pale blue and red, repainted every year. Between the trees, close to the houses... the sky is blue, blue. You can find Tahiti in Russia, too."[13]

Whereas Gauguin, in search of his exotic paradise, had to leave France and travel to the Pacific Islands, Larionov found it enough simply to pass through the gate of the log fence that surrounded his estate. That hot Tiraspol summer, that southern region by the Black Sea - in 1903 Larionov and Goncharova visited Odessa - blended impressions of real life and art to give birth to Larionov's personal Tahiti: the streets with their luscious palm trees and wandering blue pigs, shining views of the sea with its sun-reflected scarlet water, thick shadows spreading themselves along the whitened walls, and lilac women bathers with their Polynesian faces (“A Blue Pig", 1909-1910, Centre Georges Pompidou; “The Sea", 1910, Nizhny Novgorod Art Museum; “Peasant Women Bathing", 1909, Kovalenko Art Museum, Krasnodar). On the far shore of the Black Sea lies another exotic land, Turkey, with its aromas of southern fruit sold by women in the bazaar, and of tobacco from stores with signboards featuring a Turk smoking (“A Turk. From a Visit to Turkey That Didn't Happen", 1910, Tretyakov Gallery). To visit, you have only to “animate" the shop's signboard and imagine yourself “Travelling to Turkey". Larionov even came up with an incredible tale of “a business trip to the Turkish coast", allegedly organized annually for him by the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture.

Every year the artist could hardly wait to go back home, to Tiraspol. Although he felt himself at ease in Moscow - and later in Paris, too - in his art he was never a “townsman". The city brought out his “organizational skills, so rare in Russian artists",[14] but he did his work in the provinces, where the relentless pulse and business-minded attitudes of the big city had not yet got the better of nature and life itself. It was there that he found ladies “seductive like Venuses, in dresses the colour of the rising sun, umbrellas hovering over their heads like huge butterflies. And all this while moving along pavements that shine like polished steel. walking amongst women selling flowers that peak out at you from their small pails and little jugs."[15] Larionov with his absolutely special gout a la vie relished this provincial life, its people dancing and fighting in taverns (“Dancers", 1909, Tretyakov Gallery), its grotesque female circus performers, and the barbers who seem to have stepped straight down from their signboards (“Barber", 1907-1909, Russian Museum). “It is here that his provincial dandies come to life, their natural milieu somehow realized," Romanovich wrote, “nearly all of his barbers had their prototypes in real life."[16]

-

Barber. 1907

Oil on canvas. 77.5 × 59.5 cm. Russian Museum

“A Soldier's Life" reflects another new stage in Larionov's life and artistic career, when in the 1910s the artist spent time as a conscript in army camps. This new military experience, combined with the artist's interest in primitive art, produced astonishing results. He added shooting-range targets to his lubok (cheap popular print) collection, and was now including examples of this new primitive art - soldiers' art, drawings and inscriptions on barrack fences and walls - into his compositions. He was not simply engaging with new narratives: his colour scheme was changing too, as he started to use plain “earthy, down-to-earth" colours to describe the soldier's life.[17] The artist used such a “muddy" palette to produce the finest colour combinations. At one extreme, there are images of the life of the soldier, to which Larionov introduces an autobiographical motif, featuring paintings on a barrack wall (“Morning in a Barrack. Motif from a Soldier's Life", 1910, Tretyakov Gallery). At the other, this is life looked at through the lens of primitive art, as in “A Cossack", resembling some simple handmade toy (1910-1911, Tate Gallery, London); “A Soldier Smoking" (1910-1911, Tretyakov Gallery); and “Soldier Resting" (1911, Tretyakov Gallery), which depicts a soldier with a kiset (tobacco pouch) casually sprawled on the ground. This army series has all sorts of images: soldiers' portraits, landscapes and interiors, even a “soldier's Venus".

That leads naturally on to Larionov's “Venuses". Larionov treated the eternal theme of classical art without particular deference. “There is no copy in any traditional meaning of the word. There is a work of art spurred into being by an engraving, painting, scenery, etc.", he wrote in his Rayonism manifesto.[18]

Copies and replicas of famous compositions are a normal part of artistic practice, and Larionov was simply “expanding" the range of “works to emulate", putting everything on an equal footing - classical images feature alongside folksy Venuses depicted on cheap rugs or shown in tavern-wall prints. Using a traditional composition, the artist “adapted" it for different purposes, as if targeting the “widest possible audience", and created an entire series of “national" Venuses. He even designated one such Venus for himself, as the inscription “Venus and Mikhail" made directly on the canvas makes clear (“Venus", 1912, Russian Museum). This carefree, cheerful damsel with pigtails - his personal Venus - is close kin to the figures featured on Larionov's famous tetraptych, “Seasons" (1912, Tretyakov Gallery; Centre Georges Pompidou).

The recurring natural cycle of the seasons, each new one replacing the last, unites those seemingly incompatible concepts, changeability and repetition: this series might be called a “clue" to the work of Larionov, whose artistic career had a similar cyclical quality. It is significant that the artist repeated many of the themes from his Russian period in the graphic works of his Parisian period, as if distilling them into formulae. “An artist who doesn't change is dead": such is the formula of Larionov's art.[19] His compositions from the “Seasons" series are the quintessence of what is regarded today as Larionov's “discoveries". The artist plays with the viewer in his own way. The seeming naivety of the images, the inscriptions in childlike handwriting, with letters slightly coloured and complete with spelling mistakes, “disguises" an exquisite artwork, a secret demonstration of consummate workmanship achieved by minimalist means and built on the subtlest gradations of colour produced with varied movements of the brush.

In “Seasons", the artist incorporated text into his imagery for the first time. This part of the exhibition also presents the lithographed books he produced in 1912-1913: collaborating with Alexei Kruchenykh and Velimir Khlebnikov, Larionov helped to originate the genre of the livre d’artiste, designer books in which image and handwritten text are inseparable from one another and where the style of script is an important element of the whole.

Larionov created another self-portrait (1912, collection of Pyotr Aven) at this time. The composition introduces a confident, mischievous artist: his casual dress, the look on his face, and the bright colours seem to be “opening him up" to the viewer. As if it says: this is the one, the creator of the “Knave of Diamonds", “Donkey's Tail" and “Target" exhibitions, whose very names and assorted displays caused so much indignation, this is the organizer of those scandalous cultural actions whose each new direction is anticipated with curiosity and apprehension.

The exhibition continues with Futurism and Rayonism. Together with Kandinsky and Malevich, Larionov transcended the world of material objects: the dispute about who came first in this field has become one of the most intriguing stories of 20th century art. There are different versions of the origin of Rayonism, too: in different years Larionov provided varying accounts of the meaning and origin of the movement, coming up with witty “academic" explanations. Whatever you think of his theories, it is obvious that Rayonism was no accidental occurrence in the artistic life of Larionov, Southerner that he was. The early Rayonist works are permeated and saturated with shining yellow hues, while beaches and the sea were among the Rayonists' favourite themes. As was often the case with Larionov, the initial impetus might have come from a fleeting glimpse of nature, but as such impressions were “re-interpreted" on the canvas and turned into dabs of colour and pencilled hatching, they were given a new life in line with the rules of art.

Rayonism is not so much a technique as a means of relating the process that fascinated the artist so much - the “creative making" of a painting, its emergence from its constituent colour mass. This is why the artist could easily step over the narrow boundaries of his discoveries, slightly mocking both himself and the viewer of his pictures. Each work was an individual project, its birth occasioned by many factors. Larionov did not want his viewers to be able to stop in their tracks: there is no feeling any confidence here that “the truth has been discovered once and forever".

The war and Larionov's military service marked a watershed between the artist's Russian and French periods. Returning wounded from the front, a demobilized conscript, Larionov participated in the exhibition known as “Year 1915", where he displayed not paintings but collages and assemblages, including “Portrait of Natalia Goncharova" (Tretyakov Gallery, 1915). After that he left Russia on Diaghilev's invitation, to join the impresario's company in Switzerland. As fate would have it, he never returned to his homeland.

Another major section of the exhibition, “A Man of the Theatre", is devoted to Larionov's work for the stage. Larionov was not only a set-designer who, working with Goncharova, ushered in a new era in the life of Diaghilev's “Ballets Russes" - he also had a passion for ballet. The show features sketches of costumes and sets for such celebrated productions as “The Midnight Sun" (Le Soleil de Nuit, 1915), “Fairy Tales" (Les Contes de Fees, 1916-1918), “The Fox" (Le Renard, 1922) and “The Buffoon" (Chout, 1915, 1921), as well as sketches of dance scenes, “ballet-inspired" pictures, portraits of dancers and choreographers, and the layout of a book on the history of ballet on which the artist worked in the 1920s-1930s. At its centre is the costume of the Buffoon that Larionov designed: the mask of the jester, the Merry Andrew, the spieler was a favourite of the artist, all the better to whip up some stage drollery, to generate an atmosphere of surrounding theatricality. In “The Buffoon" Larionov fulfilled his dream of working in a dual capacity, as both designer and choreographer. Of all the artists involved in the creation of Diaghilev's ground-breaking theatrical projects of the 1910s, only Larionov actually staged a ballet at a major Paris theatre.

The section “In the Paris Studio" highlights both the beginning of Larionov's new creative cycle and what could be defined as his return to the artistic challenges of his Russian period. But whereas during his Russian period Larionov was “open" to the outside world - the windows of his studio were always wide open - his studio in Paris was an isolated, enclosed space where the artist carried out his artistic experiments with a solitary devotion. Busy with his theatre projects, Larionov only returned to painting in the mid-1920s, and his works appeared in series, each new one concentrated on a particular artistic quest. He was now mostly focused on drawing - tellingly, at his 1931 solo show at the Tchisla Gallery, paintings and graphic works were displayed in equal proportions. Experimenting in his isolated “laboratory", he was exploring the properties of the texture and colour of paper, interested in the different ways in which fluid paints and pastels could be applied. He produced several series of non-figurative compositions (“White", “Compositions of Yellow Paper", mid-1920s to mid-1930s, Tretyakov Gallery). In “Compositions with a Frame" (mid-1920s to mid-1930s, Tretyakov Gallery) an abstract geometric figure, with a large bold signature “LARIONOV" beneath it, suddenly turns into the frame of a composition bordering a landscape, a genre scene, a still-life. This playful treatment of objects suggests that any representation symbolique can conceal something figurative. Two pivotal “narratives", comfortably co-existing in the artist's studio - nudes and still-lifes - come to define his easel paintings; sometimes both themes are united in a single work, with a still-life including drawings of a naked figure. Seamlessly integrated into the composition of the paintings, these graphic pieces emphasize the importance of this technique for the artist.

Larionov's new journeys to the South inspired his return to painting, as the fishing villages and small seaside towns of France's Mediterranean coast came to replace his beloved Tiraspol. These new destinations gave him new themes too, among them la vendange, the grape harvest, with its women carrying baskets full of grapes - he called them les porteuses, the carriers. It is an exploration of how a colour turns into a shining light, which highlights, via contrast, figures against black backgrounds, or blends them with their environment, to the point when they become a colour spot or a splotch of light on a light-toned sheet of paper. Larionov found an equilibrium between the figurative and the non-figurative, or rather between two poles between which lies a space for metamorphosis. He “runs through" this gamut, from object to sign and back, like a pianist playing scales: in pencil drawings, from object to sign; in gouache and tempera pieces, from figure to colour spot. The series of drawings on display at the exhibition are an example of inspired, consummate workmanship and demonstrate a variety of pencil and charcoal techniques. In the gouache pieces he almost investigates the properties of that form, the changing richness of tone in the water colours themselves. Gradually “condensing" the colour, Larionov “extracts" an object from it - fishes, or pears on a table. As Larionov himself put it in a letter to Goncharova, he was “finding a new form"[20] for the depiction of the sea, creating a series of elegant black watercolour compositions, which can be best understood by taking a close look at his “Sea Landscape". These pieces seem to equalize the fluidity of watercolour and the fluid element of water itself, the object as well as the method through which its image is produced. Larionov thus found a new path to non-figurative imagery - no longer in need of “academic" explanations and justifications, it poeticized technique itself, the very handicraft of the artist.

The final section, “Larionov the Collector", is devoted to another great passion of the artist. In his Paris years, when the artist began once again to assemble a collection, he focused on theatre.[21] Among its unique elements are ballet photographs and books on the history and theory of ballet, many of which were given to him as presents and carry dedicatory inscriptions and autographs of illustrious theatre-makers, dancers and choreographers. The collection of rare photographs of dancers and choreographers as well as scenes from productions of the “Ballets Russes", the “Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo" and the “Original Ballet Russe", is now held in the Department of Manuscripts and library of the Tretyakov Gallery. Larionov's library, which it is particularly interesting to introduce to the public, deserves special attention. It includes books on a wide variety of subjects - from the history of theatre, and costume and set design, to Oriental and Old Russian art - in many languages. Alongside that is a plethora of other material: fiction published in Larionov's lifetime, both in France and in the Soviet Union, plays and collections of poetry, works of philosophy, bound volumes of magazines and postcards, and art albums - it is hard to say exactly where Larionov's curiosity and professional interest morphed into a collector's mania. Although money was always scarce, the artist rented a separate storage facility for his library and collections.

The exhibition concludes with a selection of Russian luboks and engravings: they represent only the highlights of this part of Larionov's collection, which runs to thousands of items. It includes elegant Japanese engravings, Chinese lubok popular prints, and Japanese katagami - paper stencils for dyeing textiles. The Vietnamese Dong Ho folk woodcuts, with their bright images on a tinted foundation, prompt consideration as to whether they might have inspired Larionov to experiment with paper of different tones and textures, as he did in his Parisian years.

Larionov was an artist who never tired of “taking a close look" at the world around him. As the artist's collections and his own works show so vividly, he drew inspiration from different sources, every new impression stimulating his creative activity. More than just a display of art that introduces the different stages of the artist's artistic biography, the 2018 Larionov exhibition attempts to reveal his creative energy and volition, the interest in and love for life that is at the core of his artwork. In 1912, Larionov painted “Happy Autumn", a golden-yellow picture that perfectly captures his joie de vivre - and we trust that such happiness defines this Autumn exhibition no less.

- By 1930, the collection of the Tretyakov Gallery included 16 works by Larionov.

- “Mikhail Larionov - Natalia Goncharova. Masterpieces from Their Parisian Period. Painting". Moscow, 1999. “Mikhail Larionov. Natalia Goncharova. Their Parisian Legacy at the Tretyakov Gallery. Graphics. Theatre. Books. Memoirs". Tretyakov Gallery. Moscow, 1999.

- The series included four works: “Winter" and “Spring" belong to the Tretyakov Gallery, while “Autumn" is at the Centre Georges Pompidou. Unfortunately, the location of the fourth composition, “Summer", which was at one time held by a private collector in Europe, is presently unknown.

- Eganbyuri, Eli. “Mikhail Larionov. Natalia Goncharova". Moscow, 1913. P. 27. Hereinafter - Eganbyuri.

- This article applies the term as it was used in Larionov’s own time. Today, such references would be about the influence of the French Post-Impressionists on the artist.

- The Russian art exhibition was shown at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1906. Larionov exhibited six pieces, one of which was reproduced in the catalogue. Later the artist repeatedly reminisced about how, after receiving the letter of invitation from Diaghilev, he cut short his holiday in Tiraspol and hurried back to Moscow.

- From Andrei Shemshurin's memoirs, quoted from: “Unknown Russian Avant-garde in Museums and Private Collections". Moscow, 1992. P. 134.

- Romanovich, S.M. ‘How I Remember Him’. Quoted from: Kovalev, A.E. “Mikhail Larionov in Russia. 1881-1915". Moscow, 2005. P. 509.

- Inscription on the reverse side of the drawing (Р-17909): “Goat’s eye, orange-coloured, with a black pupil".

- Quoted from: Pospelov, G.G. “The Knave of Diamonds. Primitive Art and Urban Folklore in Moscow Painting of the 1910s". Moscow, 1990. P. 39.

- Eganbyuri. P. 24.

- Larionov was also a sculptor. Perhaps the forces at play here were, on the one hand, Goncharova’s influence, and on the other, a universalist trend typical for that time and for many of its artists.

- Stenberg, Erhard. ‘Goncharova Reflects on Her Past’. In: “Goncharova and Larionov. Fifty Years at Saint-Germain-de-Pres". Paris, 1971. P. 214.

- Eganbyuri. P. 25.

- Larionov, M.A. ‘Lyrical Fragments’. Published by E.V. Basner in: “N. Goncharova and M. Larionov. Research and Publications". Moscow, 2001. Pp. 192-193.

- Kovalev, A.E. Op. cit. P. 513.

- G.G. Pospelov wrote about this. In: Pospelov, G.G.; Ilyukhina, Ye.A. “Mikhail Larionov. Painting. Graphics. Theatre". Moscow, 2005. Pp. 110-111.

- Larionov, Mikhail. “Rayonism". 1913.

- Loguine, T. ‘Spirituality and Education’. In: “Goncharova and Larionov. Fifty Years at Saint-Germain-des-Pres". Paris, 1971. P. 232.

- Larionov wrote to Goncharova about this. In: Mikhail Larionov’s letter to Natalia Goncharova, September 12 1930. Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 180, item 4570.

- Already by the 1910s Larionov had accumulated a vast collection of luboks: the catalogue of his 1913 exhibition lists more than 300 such works. What happened to this collection, however, is not clear. In 1915 Larionov was leaving Russia “for a short time" and without much baggage. Later, at the end of the 1920s, Lev Zhegin on Larionov’s request sent his and Goncharova’s artwork to Paris; their letters contain no reference to the collection being mailed. And considering the mailing costs, as well as both artists’ chronic shortage of funds, the collection is most likely to be found in Russia. It is possible that only a handful of such items was sent to France.

Oil on canvas. 100 × 89 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas. 80.5 × 65 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Gouache on cardboard. 71.3 × 97.7 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Oil on canvas. 98 × 103.4 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Oil on canvas. 69 × 69 cm. Nizhny Novgorod Art Museum

© ADAGP

Oil on canvas. 61.6 × 86.7 cm. АВА Gallery, New York

Oil on canvas. 95.3 × 100.7 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Oil on canvas. 65.5 × 79 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Gouache, tempera on paper. 83 × 69.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Oil on canvas. 99 × 77 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Oil on canvas. 127 × 140 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas. 68.2 × 65.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas. 99.5 × 129.5 cm. Nizhny Novgorod Art Museum

Oil on canvas. 52.7 × 44.8 cm. Russian Museum

Oil on canvas. 142 × 118 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Tempera on paper. 50.6 × 35.1 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Gouache, tempera, collage on cardboard. 99 × 85 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gift from V. Moritz, 1961, Moscow

Lead pencil and watercolour on paper. 45.5 × 70 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gift from Evelyn Cournand, 1983, Paris (collection of P. Pyankova and Evelyn Cournand)

Watercolour, graphite pencil, gouache on laid paper. 59 × 44.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Gouache, whitewash, charcoal on сardboard. 37.9 × 26.8 cm

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Oil on canvas. 151 × 150 cm. Tretyakov Gallery. The painting is based on the early composition “Ladies’ Hairdresser” (1909-1910, private collection)

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Sergei Diaghilev’s “Ballets Russes”. Photograph with Léonide Massine’s gift dedication. 1917

Tretyakov Gallery

Gouache on yellow tinted paper. 51.4 × 34.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Gouache, graphite pencil, tempera on paper. 52.5 × 40.2 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Gouache on yellow paper. 49 × 65 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Gouache on brown wrapping paper. 50.1 × 38.7 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Oil on canvas. 65.2 × 46.2 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gift from Evelyn Cournand, 1983, Paris (collection of P. Pyankova and Evelyn Cournand)

A Couple Playing Music

Colour woodblock print, tinted paper. 48.3 × 31.3 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris

Typography print, aniline dyes on paper. 34.5 × 44.7 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Gifted in the will of the artist’s widow Alexandra Larionova-Tomilina, 1989, Paris