The Second Russian Avant-Garde

The exhibition "Drugoe Iskusstvo" (The Other Art, 1988) in the Tretyakov Gallery had an unprecedented impact on the consciousness not only of the general public, but also on the country's whole artistic community. The Socialist- Realist artists, headed by the academicians and correspondent members of the Soviet Academy of Arts, were shocked by the very fact of such a massive and irrevocable "intrusion" by nonconformist artists into their territory - a location that had been used by them, and only them, for more than half a century. The "intruders" organized their own schools, working out their new stylistic methods, using their own languages, and building another ontological picture of the world. Today, given that the Bolsheviks have died out as swiftly as the ancient Greeks, and that the Socialist-Realist canon is already being studied by Western art critics on an academic level, the whole dramatic situation connected to the exhibition belongs to history. It became clear that Socialist Realism - though really exotic, unnatural, extremely ideological, as well as aggressive and populated with many anonymous participants, who were far from free - was the school, one of the many dozens of artistivc directions of the 20th century: it was characterized by its peculiar stylistics, method and language, and its own "false" picture of the world. In that aspect, the school was like other art schools, including the schools of "The Other Art" of 1957-1988, which manifested and constituted themselves in the framework of the second wave of the Russian avant-garde. The situation had changed dramatically: now the field of competition was not only the country's main exhibition location, the Tretyakov Gallery, but also an international perspective which opened following the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain.

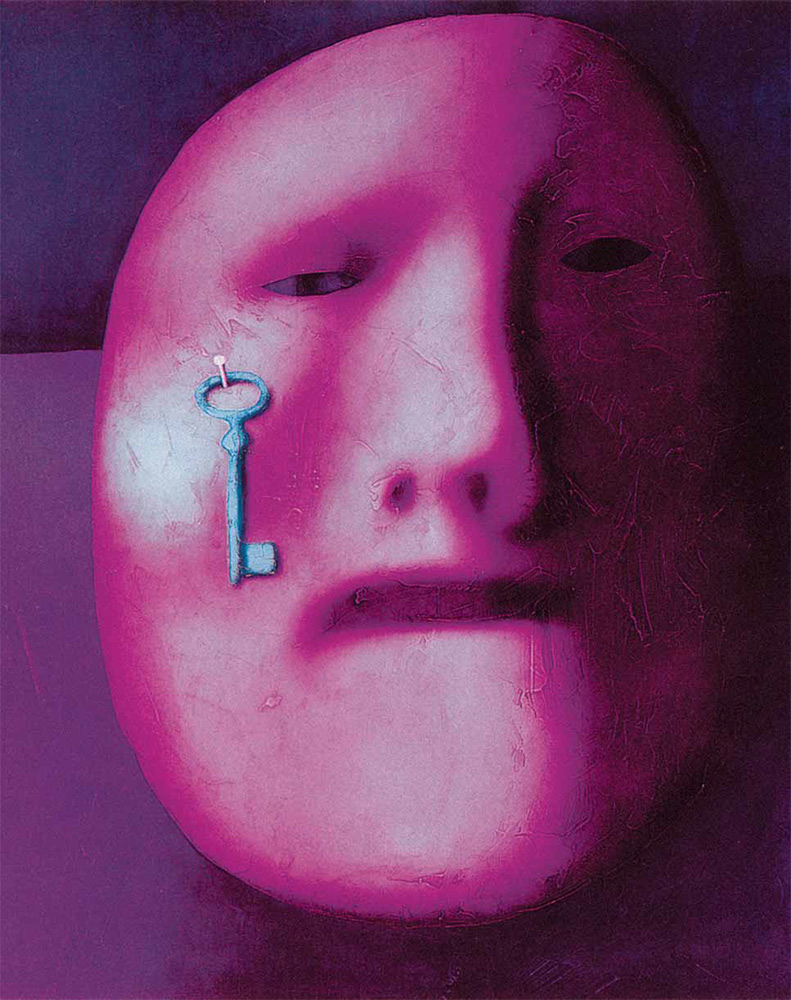

Oleg TSELKOV. Face with a Key. 1989

Oil on canvas. 100 by 100 cm

The last nail in the coffin of Socialist Realism came from the newlyelected president of the Academy of Arts, Zurab Tsereteli, in 1997, who formulated a new slogan of Russian artists: From Socialist Realism to 'Art for Art's Sake' (DI, #1, 1998). During its first five years, from 1997 to 2002, the programme of the reform of the Academy was realized: the reconstruction (on the basis of recreated religious paintings) of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour; and two museums of Contemporary Art presented - as, in its time, was the Tretyakov Gallery - to the city of Moscow. A similar policy of post-modernism was followed in building up the Academy's exhibition programme; even post-modernist artists such as Eduard Drobitsky, Natalia Nesterova, Tatiana Nazarenko, Boris Messerer, Alexander Rukavishnikov, Olga Pobe-dova and Aidan Salakhova were elected to the Academy.

The series of commemorative, anniversary exhibitions of such nonconformist artists in the Tretyakov Gallery recalls just such a parade of victors. The "other art” has gained worldwide recognition over the last 20 years: Ilya Kabakov is among the most internationally-known such figures.

The grand style of the 20th century is "suprematism". The architectonics of Malevich in his images of skyscrapers can be seen in all the capitals of the world, while his "The Black Square" became a symbol of 20th century art. Thus the 1996 exhibition in Germany was titled, "From Malevich to Kabakov". Eduard Shteinberg is in a constant living "dialogue with Malevich". Komar and Melamid continue their sots-art, and its mockery of Socialist Realism. The international reputation of Russian avant-garde from the beginning of the 20th century is not only confirmed, but gains a triumphant significance from the "second Russian avant-garde", a name that now is associated directly with the "Other Art".

The anniversary exhibitions of such renowned non-conformist artists appeared almost simultaneously at the Tretyakov Gallery, given the closeness of the dates of birth of the artists concerned: Erik Buklatov and Ilya Kabakov were both born in 1933, Oleg Tselkov in 1934, Ivan Chuikov and Yury Kuper in 1935; Viktor Pivovarov, Dmitry Plavinsky and Shteinberg, in 1937. These dates, as if by providence, were associated with the so-popular historic Communist era five-year plan of 19331 937. The non-conformists celebrate their 70th birthdays in the period of 2003 through to 2007. As Ilya Kabakov has stated: "Art is to be conquered by a gang.”

Kazimir Malevich died in 1935. He died a hunted figure, overwhelmed by grief. No one knows the location of his grave in Nemchinovka, a small village near Moscow. Vera Yermolaeva and Alexander Drevin were shot in 1938. Shteinberg's father - Arkady Akimovich, a poet and an artist -was twice sent to the Stalinist GULAG. Vladimir Sterligov, who tutored a group which was later titled a school named after him, met Vera Yermolaeva in a camp near Karaganda. Larionov and Goncharova, El Lissitzki, Vasily Kandin-sky, Osip Zadkin, Yakov Lipshitz, Naum Gabo, Natan Pevzner, Ivan Puni - this list could easily be extended - were forced to leave Russia.

In 1 957 the non-conformist artists started from a "zero point" - from "The Black Square", which is the sign of zero-colour, zero-form and zero- content of painting. At the same time these artists had a special task, a special aim: to develop their own non-literary and non-bookish language of painting. These non-conformist artists received academic education: Bulatov, Kabakov and Oleg Tselkov studied at the same Central Art School affiliated to the Academy of Arts, and have known each other since 1949. Bulatov and Kabakov graduated from the Surikov School. And the unruly Oleg Tselkov, who was dismissed from two academic institutions in Minsk and Leningrad, graduated from the Theatre Institute where his tutor was Nikolai Akimov. Many non-conformist artists received a brilliant education, in spite of the fact that "formalism and abstractionism" were taboo in the Soviet Union. Anatoly Zverev and Vladimir Yakovlev remain the exceptions, but it seems they were born to become "self-made".

In 1962 Khrushchev acquired the title of "pogrom-maker" at the Manezh Exhibition Hall in Moscow at the exhibition of "30 years of MOSKh". The "Chief of Socialist Realism" was furious not only with the old members of the "Jack of Diamonds” group, but also with the young abstractionists from the Belyutin circle. There were particular individuals who found themselves in the focus of Khrushchev's keen attention - the painter Gayana Kazhdan, and the sculptor Ernst Neizvestny. In the USSR, the first five dissident years were those of 1957 to 1962, and during this short period non-conformist artists came to constitute and differentiate themselves, standing apart from the young Soviet Socialist-Realist artists. The stylistic choice of the first, and the conformism of the latter, determined their significance in world art: "My confrontation with Soviet power lies only in the sphere of stylistics", declared the outstanding non-conformist writer Andrei Sinyavsky at his trial in 1965.

The legendary Bulldozer Exhibition of 1974 - celebrating its 30th anniversary this year, too - demonstrated once and for always the attitude of the Soviet state to the "other art." Many non-conformist artists were squeezed out from the country: the exodus of 1971-1987 allowed them to gain world recognition, most of all during the "Gorbachev-boom" of 1987-1992. The triumphant exhibitions of such artists at the Tretyakov Gallery mark their return to their homeland.

Any short review of the anniversary exhibitions at the Tretyakov Gallery needs to be preceeded with some comment on the first solo-exhibition of Mikhail Shvartsman (1926-1997) there in 1994. Shvartsman occupied a unique position among non-conformist artists: he was their guru, almost a Biblical sage and spiritual leader. To be allowed to visit his studio - though he had never had any such space, and worked at home - was considered a great honour for any artist. And if all the non-conformist artists associated themselves with the metaphysic trend in art, Shvartsman insisted on sacral intentions, the latter being the source of his hierachy of language, theurgy of method and spirituality of style.

Something mysterious always exists in any creative activity - a mystery even for the individuals concerned. Shvartsman's influence on contemporary artists cannot be overestimated.

The anniversary exhibitions of 2003-2004 in the Tretyakov Gallery opened with the presentation of the father-founders of the "Moscow conceptual school", Erik Bulatov, Ilya Kabakov and Viktor Pivovarov: they called themselves the "genius" sheshtidesyatniks (the generation of the 1960s). Their genius put them into direct opposition with the dissident sheshtidesyatniks, not to mention the conformists of that period. By the 1970s their "genius" managed to reach a certain level of perfection of conceptual practice, and organized - through the so-called "apartment exhibitions" - a wide conceptual movement in the USSR. But, as is of great importance, the conceptualists realized, understood and interpreted the methodology and theory of the concept. Pivovarov made the most exhaustive retrospective presentation of his works at his exhibition in the Tretyakov Gallery (perhaps because Prague is close to Moscow?) In the halls of the Gallery on Krymsky Val he showed his conceptual paintings, drawings, objects and installations, not to mention some projects, albums and papers from Soviet housing and communal services, and the "blank" albums with the pencil set invitingly to visitors, with the apparent exhortation: Write! Draw! Think!

In the picture-tale from the album "Litsa" (Faces) the artists refers to somebody and to himself, asking: "You remember, don't you? My flat on Maroseika... We were having tea and speaking about our friends who shouldn't have left the country" (1979); in the light-blue background there is a white silhouette-portrait of a man. His head - down to the collar of the shirt - is filled with images of a part of the kitchen interior where this "tea meeting" took place: it is a touch very typical for Pivovarov. In the visual texts at the exhibition the viewer-reader perceives a comprehensive realization of the following conceptual principles, formulated by the author:

(1) revision of the role of colour in the picture;

(2) rejection of the so-called "sensual deformation" of the object;

(3) rejection of the artistic gesture;

(4) the destruction of spacial unity in the picture;

(5) breaking logical connections among objects;

(6) open painting - "open" in the sense that the conceptualist-artist can freely take it from the picture and set it into the space between the picture and the viewer/co-creator (as was done by Malevich in "The Black Square");

(7) alienation - "the picture alienated from the artist receives the opportunity to speak for itself";

(8) painting as a literary genre.

Of course, this list of conceptual means is "open" to a number of supplementary entries - it could be continued a-la Pivovarov. For example: (9) the picture as a semiotic space; (10) from the image to the sign, etc. But if all these are to be considered seriously, one sees the radical revolution that took place in art, the revolution made by the concept- ualists: the artistic paradigm was changed. New languages, methods and styles in the "picture-puzzles" were ready to move from the visual space to a literary one, but could not overcome the borders between them - such is the methodology of Moscow conceptualism.

Erik Bulatov's exhibition was different: in his pencil studies he reveals something of the mystery of the birth of the ideas behind his future pictures. Created with the particular delicacy which is characteristic of Bulatov, these drawings create a deeper understanding of the artist's path through the world. He himself has said a great deal about "the surface, space and light" in his pictures, about his creative results and about his teachers, first and foremost Favorsky. Art critics may rank Bulatov among the conceptual- ists, or the hyper-realists, sots-artists, or surrealists - but any such terms do not reach the core of Bulatov's creativity. One thing is clear, however: Bulatov is unique in his ability to work with various sign systems, "contra signatures". He is able to combine the iconographic signs of a photo-portrait or a photolandscape with seemingly incompatible conventional signs: letters, words, verbal texts, or non-verbal signs - like the official emblem of the USSR that sets like the sun into the depth of the ocean; and further, "alien signs", the letters that start to live according to the laws of "direct perspective" familiar from landscape, as the landscape itself is "pulled" beyond the space of the vertical canvas. And like any other conceptualist Bulatov has another space in front of the canvas - the space of the interaction between the artist and viewer. Then there is the third, physical space. And in the metaphysic space "inside the frame of the painting" there are further spaces: semiotic, form-colour (visual), compositional-syntactic, pragmatic, meaningful (a-logical). Within all these physical and metaphysical spaces Bulatov must build his "meta-space", inside which "the game with cultural codes" lets him reach "the highest expressiveness" of the final picture.

Ilya Kabakov's "Spiral-labyrinth" in the hall of the Tretyakov Gallery was associated with the "Tatlin Tower". Kabakov, the most radical of the conceptualists, is not afraid to be blamed for such feeble imitation; he gives no further thought. He has said that a conceptualist is painting not only on a canvas, but also on the viewer. In his installation of the "communal apartment" - a symbolic symbol of socialism - the viewer enters, in fact literally steps into the primarily-designed element of the installation. Any such gesture from the viewer to Kabakov's installation seems natural; any aggressive reaction matches the idea. Thus, Kabakov's spiral-labyrinth naturally and easily encompasses Tatlin's spiral-tower, Lenin's thesis on the spiral development, and a vaginal contraceptive spiral. The number of verbal commentaries to Kabakov's "A Fly" is really countless, and their philosophical quality beyond imagination.

The term "sots-art" was smartly formulated by Komar and Melamid in the 1970s, though works of art in this style had already appeared in the heroic 1960s, including those of Oscar Rabin, Boris Sveshnikov and Mikhail Roginsky which were shown at underground exhibitions. The viewers were largely foreigners, diplomats, journalists and tourists. Bulatov, Ilya Kabakov and Pivovarov are sots-artists too, but of another kind. Oleg Tselkov was never deemed a sots-artist, though his exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery seemed almost like a "voice in the sots-art wilderness". Tselkov is different from the rest, a pure painter working with colour and light. He marvels at the texture of his paintings. A real professor of pictorial composition and structure, he is at the same time a figurative painter - and, in an even narrower sense, a portraitist. However, Tselkov paints a very special portrait, effectively one and the same work: not alike, but nevertheless somehow "one and the same", the "portrait of the portrait". In such terms the artist himself defines his "genre". Tselkov's art is called "re-ceptualism", the art of "second reflection": Tselkov had to compare and contrast portraits of all times and all people in order to reveal and expose, and visualize to the viewer an invariant of the "portrait." The opposition of his images, icons and Tselkovits in the framework of the picture and its double provides their absolute identity, while the colouristic characteristics of his canvases contradicts this identity. Their luxurious colour spectrum contradicts the plain wretched ugly mugs of the Tselkovits. The brightness of his colours overwhelms the hundred colours of his contemporaries; collectors are not inclined to buy Tselkov - his works dominate other works in collections by the power of their colour. Over the years Tselkov's palette has changed from red to violet, using the full spectrum, but always remaining awfully powerful.

The works of the abstractionists - Nikolai Vechtomov, Yuri Zlotnikov and Shteinberg - used the language of colour, but their pictures and creative effort on the whole represented three absolutely different schools of the second Russian avant-garde. The Lianozov school - to which Vechtomov belonged - was the first to make a non-figurative challenge to Socialist Realism, as early as 1957. A few courageous artists - Lev Kropivnitsky, who returned from a Stalinist camp in 1956, Lidia Masterkova, Vladimir Nemukhin, Nikolai Vechtomov and Olga Potapova, the wife of Lev Kropivnitsky - turned to abstract art. They worked in close association, but nevertheless managed each in their own way to follow their own paths in drawing, colour and texture. Shteinberg is their counterpart in style and manner- he clutches at the "suprematism rope”, paying little or no attention to the existence of a 70-year gap in the history of the Russian avant-garde.

The retrospective exhibition of Dmitry Plavinsky, who has lived in the USA for fourteen years, included a few works that might be regarded as abstract. But Plavinsky is a representative of another school of art: in the 1960s, quite unexpectedly for those times, the phenomenon of "religious art" appeared in the Soviet Union, represented by Plavinsky, Alexander Kharitonov and Boris Kozlov. These brilliant masters of drawing and painting used in their works certain "forgotten matters": the Bible, the shroud, the floral motifs and colour palette of Byzantine-Russian icons, the architecture and interiors of cathedrals, and even the process of the liturgy. Plavinsky is the brightest character among them, working in many genres and techniques. His texture and nuances of colour catch the viewer's eye, and almost all his pictures are real masterpieces. As a result, he has often had to make original copies, given the demand from collectors. Today, Plavinsky works in purely "secular spheres”, making maps of Manhattan, of the canals of Venice, and objects taken from life and still-life. The exhibition embraced both his Moscow and New York periods, with the viewer becoming involved in an analysis of the process of the development of Plavinsky's pictorial language and original stylistic devices - another indisputable, and brilliant, representative of the second Russian avant-garde.

Oil on canvas. 200 by 200 cm

Gouache. 33 by 25 cm

Watercolour on paper. 50 by 38 cm

Ink, watercolour on cardboard. 65 by 69 cm

Oil on canvas. 65 by 70 cm

Tempera on panel. 75 by 100 cm

Tempera on panel. 63 by 63 cm

Oil on canvas. 160 by 170 cm

Oil on canvas. 170 by 150 cm

Tempera on paper. 60 by 80 cm

Oil on canvas. 150 by 125 cm

Oil on canvas. 130 by 82 cm

Oli, acrylic, sand. 300 by 300 by 7 cm

Oil on hardboard. 141 by 141 cm

Oil on hardboard, collage

Installation