To Russia – On the Chance of Fate

THIS REMARKABLE STORY PAYS TRIBUTE TO THE MEMORY OF SEVERAL RUSSIANS, WHO SPENT MOST OF THEIR LIFE ABROAD BUT RETAINED THEIR SPIRITUAL RELATIONSHIP WITH THEIR MOTHERLAND AND LOVE OF ITS CULTURE.

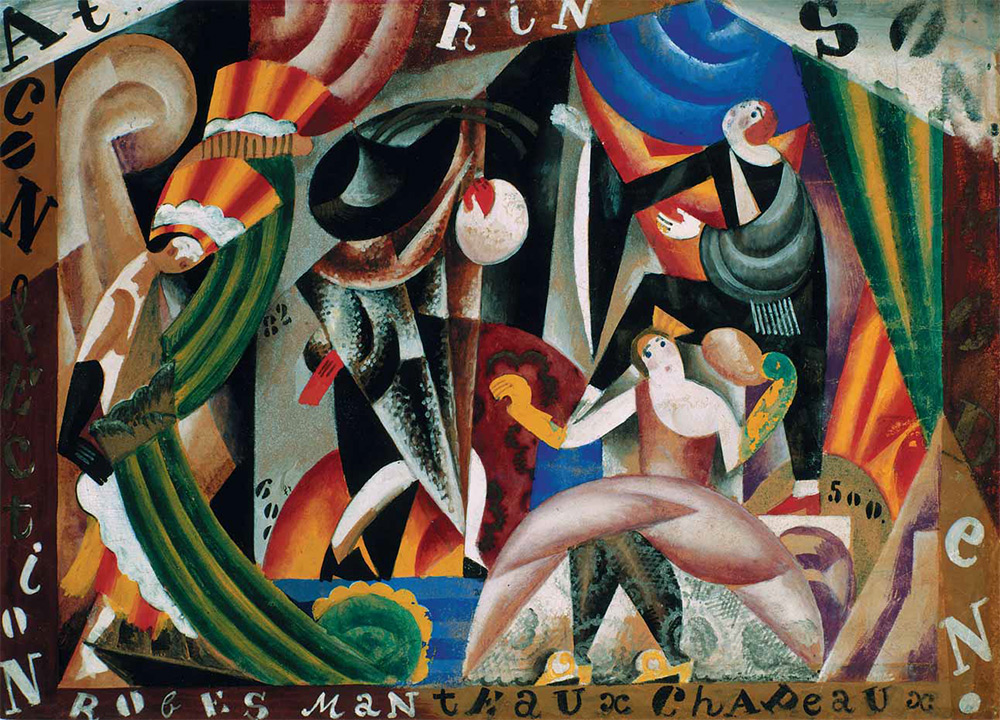

Pavel TCHELISHCHEV. A Shop Window. Sketch for a Theatre Curtain

Gouache, bronze, grey powder on paper, 23 by 32 cm

In 1984 the Soviet Ministry of Culture received a letter from a lawyer's office in London, informing them that according to his wife's will, Dr. Isaac Etkin wanted to present works by Russian artists, namely those of Mstislav Dobuzhinsky and Natalia Goncharova, to a Russian museum.

I made enquiries about the Etkins and found out that the names of Helen and Isaac Etkin were not known in collectors' circles.

I flew to London late at night. Never having been there before, I had only three days to see the city and to carry out the commission of the Ministry of Culture, which I assumed would take up plenty of time.

Therefore, I had to hurry in order to see the museums during the day time, and to go sightseeing in the evening.

The meeting with the executor and his lawyer was appointed for the following day at two o'clock in the afternoon. Where should I go in the morning? First of all - the National Gallery. I arrived just after it opened to see at least briefly all the halls. For the first time in my life I saw works by prominent Italian - and not only Italian - artists of such quality and quantity. I was so engrossed that I was late for the meeting at the Embassy, so that the Cultural Attache Gennady Fedosov and a young lawyer had to wait for me. Fedosov rebuked me for being late, and we immediately travelled to a cosy little town not far from London. Here a respectable grey-haired gentleman welcomed us: he was Isaac Etkin, who lived in a comfortable house for the elderly.

Etkin was born in 1900 in Russia, in Vitebsk province. In 1908 with his parents he came to Great Britain, where he received higher education and became a psychiatrist. He spent his whole life in England, working in different hospitals. Throughout his life he remained interested in Russian culture, trying not to miss any opportunity to see Russian touring companies, or exhibitions from the USSR. At one such exhibition he became acquainted with a colleague, a doctor of Russian origin, Vladimir Ivanovitch Kameneff.

Kameneff had lived and worked in England from 1910. During the First World War he volunteered for the French army, adopting the name France. He was wounded at the front. After his recovery, he was given leave and went to Russia in 1916 to see his parents. There in Russia, Kameneff married a ballet dancer Helen Rozhnova (she might have danced in the ballet company "Ballet de Basil”). He worked in different organizations, including the department of the American Charity "ARA", which opened in 1921 in the Russian Soviet Federative Republic to help the starving people in the Volga region. When "ARA" was closed, he returned to Great Britain together with his wife and lived there, working as a general practitioner He treated many people from the Russian artistic elite who emigrated after the Revolution.

An expert and a connoisseur of ballet, Kameneff knew many dancers and, judging by the signatures on the sketches presented to him, he was on friendly terms with the artists who staged ballet performances. He even wrote and published a book on Russian ballet (more on which later).

Isaac Etkin made friends with the Kameneffs. They often met to visit an exhibition, or to go to the theatre. After Kameneffs death in the 1960s - Etkin couldn't give an exact date - Isaac married his widow. Not long before her death, she made a will which stipulated that some of her pictures connected with ballet should go to one of the Soviet museums. Now her will was to be fulfilled: he intended to hand over eight works.

Mr. Etkin brought eight framed works from the other room. These were undoubtedly works by Dobujinsky and Goncharova, made in different graphic techniques, and almost all sketches for the theatre. While the lawyer and the Cultural Attache were signing the papers, I asked for permission to look at the other pictures hanging on the walls. I saw a graphic portrait of Vladimir Kameneff and two more drawings which I identified as Dobuzhinskys and a theatre sketch by Pavel Tchelishchev. I told Mr. Etkin about the authorship of these two works; he seemed not to know it. And then something incredible happened, which even to this day I cannot believe. The old gentleman asked us with a cunning smile: "Would you like two more pictures in addition to the other eight?" "Yes, of course", I answered, "especially Kameneffs portrait and the sketch by Tchelishchev."

Etkin promised that he would hand over these pictures if I solved a riddle. Fedosov and I looked at each other in bewilderment. Etkin went on: "All Russians like Pushkin. Do you know his poetry?" I was confused. I love Pushkin, but who can boast to know him well? Only our distinguished Pushkinists. Etkin took a volume of poetry down from his bookcase, and said that if I could guess correctly the poem that he would read, the two chosen works would be ours'. The theme of the poem was that of a road.

The situation was more than ambiguous. It was difficult to refuse, but how to agree - I didn't know English, so there was practically no chance to guess. The prompt that the poem was about a road helped a little... The old gentleman opened the book with enthusiasm and started to read "with expression". He said that he would give me an advantage and would read the poem several times.

The first time he read out two quatrains, judging by their rhythm. I could not understand what it was. He read it the second time, and then I heard something familiar. Etkin had spoken Russian only long ago, and had thoroughly forgotten it. His behaviour during our conversation with Fedosov confirmed that: he listened attentively to our speech. There was something Russian in his English speech that helped me. I thought it over and over feverishly, and after the second or third time made a decision. It turned out to be true! It was "The Possessed", written in 1830, and the poem was really about a road.

The company congratulated me on my success and the host suggested that we should celebrate it with a glass of gin. The lawyer courteously agreed to make the necessary changes in the documents.

Now all the ten works by Russian artists of the first half of the 20th century are in the Tretyakov Gallery. Mr. Etkin also presented us Kameneffs book: "Russian Ballet Through Russian Eyes. Vladimir Kameneff”. Russian Books and Library, 1936.

Taking into account the "notorious" namesake of the author I foresaw difficulties at the customs in Moscow connected with the book. For this reason, I made sure I was given an appropriate certificate from the Embassy and it worked. A young customs official took it somewhere with the certificate and finally let it through. Later on I showed the book to experts in the history of Russian ballet - and none were aware of its existence. The copy which is now kept in the library of the Tretyakov Gallery may be the only one in Russia.

Watercolour, gouache, grey powder on paper, graphite pencil on paper, 38.4 by 27.9 cm

Gouache, ink on paper. 37.7 by 27cm

Sketch for a Theatre Costume. Gouache, graphite pencil on paper on cardboard. 31.6 by 24.3 cm

Paper, charcoal. 36,1 by 25,5 cm

Watercolour on paper. 40 by 29 cm

Sketch for a Theatre Costume. Paper on cardboard, gouache, graphite pencil. 31,6 by 24,3 cm