The Poetry of Metamorphosis. THE FLOWERS AND ORNAMENTS BY MIKHAIL VRUBEL

As if in slate-grey smoke enclosed,

From realm of grains by fairy will,

Mysteriously were we transposed

Unto the realm of crystal hills.

Afanasy Fet, “Just yesterday...”, 1864

The lines are fallen unto me in pleasant places; yea, I have a goodly heritage.

Psalm 15: 6

One could begin a conversation on Mikhail Vrubel’s decorative and ornamental philosophy with the phrase “Flowers live in honeycombs, their petals picked out by sunset rays.” It is a verbal transposition summarising the images created by the artist, and also a distant echo that introduces a metaphor belonging to Charles Baudelaire into our train of thought, a metaphor that reveals, by chance, the universal nature of art: “Des fleurs se pament dans un coin.”[1] [“Flowers swoon in a corner.”][2]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Lily. Decorative motif. 1895-1896

Watercolour, gouache, charcoal on paper. 43.8 × 45.2 cm.

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Vrubel’s flowers and ornamentation make up the genetic code of his artistic language in terms both of their intrinsic, eternal meaning and their figurative form. Rarely can you find a piece by Vrubel that is missing the sacramental transubstantiation of objective reality into ornamental patterns, similar to stylised flowers. Any researcher who sets themselves the aim of analysing the iconographic construction of Vrubel’s art in its “floral and ornamental” aspect soon finds themselves drowning in a deepening floral abyss. Natural and airy, lyrical and expressive, stylised like crystal or flattened into a rhythmic, patterned form, flowers or ornamental references to them are present in the majority of Vrubel’s work, appearing either as the heroes of the piece or as accompaniments to the main narrative composition. In the context of Vrubel’s overall visual poetics, it is entirely appropriate to speak of them as a principally important element that create a figurative reality and, in the artist’s own words, reflect “the formula of my vital relationship with nature, which lives deep within me.”[3]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Campanulas. 1904.

Watercolour, lead pencil, whitewash on paper. 43 × 35.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Vrubel certainly did have a deep individual relationship with nature, a relationship founded on mutual harmony. We can see this not only in the poetic wholeness of his actual artworks, but also in the unexpected echoes of this very real dialogue that we can find in modern life. Such an echo, for example, was discovered by the author in the course of research into archive material related to the artist’s work carried out during the winter of 2021: the herbarium entitled, as it would appear from the envelope, “From the Grave of M.A. Vrubel”, and which lay forgotten for nearly a century[4]. The laurel leaf and iris petal, retrieved on 3 April (16)[5], 1910 from Vrubel’s funeral wreath (on the day of the artist’s burial) by Eduard Spandikov, an “exquisitely ‘decadent’”[6] artist of the “Union of Youth” group, unwillingly draw a philosophical and emotional link to the flowers of Vrubel’s own paintings and drawings. The way in which they resonate with the crimson-blue blooms of some of the painter’s decorative miniatures is full of meaning (see, for example, “Sketches of Tiles with Cornflowers”, early 1890s, Museum of Applied Art of the Stroganov Academy of Industrial and Applied Arts, KP-2923/23 [sheet] and KP-2923/30 [sheet]), while these dried-out petals that have long outlived the era of Art Nouveau give us a glimpse of the link between the pulse of artistic rhythm and the elements of real life reflected metaphorically within it.

A photograph from the newspaper “Nashe Vremya”,

No. 15, April 8, 1910. Manuscript Department, Russian Museum. Fund 34.

Inventory 1. Item 67. Sheet 11

An ornamental wreath of newspaper columns almost instantly engulfed the entire Russian world, all recounting the tormented demise and tragic end of Vrubel, all splattered with a mixture of fact and fiction, all filled with sympathetic, understanding or malevolent interpretations of his work. In the week after his death, many St. Petersburg and Moscow papers published articles in his memory (“Birzheviye Vedomosti”, “Vedomosti Sankt-Pe- terburga”, “Peterburgskaya Gazeta”, “Petersburgsky Listok”, “Utro Rossii”, “Ranneye Utro”, “Ves Mir”, “Russkoye Slovo”, “Russkaya Zemlya”, “Rech”, “Novoe Vremya”, “Teatr i Iskusstvo”, “Vecherny Kurier”, “Golos Moskvy”), as did gazettes all across the Russian Empire, including “Kievskiye Novosti”, “Odessky Listok”, “Odesskiye Novosti”, “Omsky Telegraf”, “Kurskaya Byl”, “Stary Vladimirets”, “Volyn”, “Kamsko-Volzhkaya Rech”, “Bessarabskaya Zhizn”, “Kazanskaya Vechernaya Pochta”, “Severokavkazskaya Gazeta”, “Golos Yuga”, and “Yaltinsky Vestnik”. After the two requiems sung on April 2 at the church of the Academy of Arts[7], where Vrubel was taken on the day of his death (April 1) by Valentin Serov and other artists[8], other requiems were sung on April 3 at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, on April 4 at Moscow’s Strastnoy Convent (on the initiative of the Union of Russian Artists[9], and on April 5 at St. Cyrill’s Church in Kyiv[10], the walls and iconostasis of which were decorated with images painted by the artist in his youth. On April 8, the prayer “Memory Eternal” was said at Ss. Peter and Paul Church in Kazan[11]. The editor of the “Na Rassvete” Digest of Arts, Aleksander Mantel, who organised the latter ceremony, commented, “that cry belongs to the departed artist more than to any one of us. / That is all we can console ourselves with, for the reality is a timeless tombstone in a graveyard of a northern city, adorned with already withering flowers, just as the dreams of Vrubel have already withered.”[12] It was an understandable grief in the face of a tragic experience that led Mantel to overlook a different reality, the reality of art, along the frontiers of which Vrubel spent his whole life walking, despite the hardships he endured. Indeed, he walks them still, thanks to the unfading power of his works, which persuade us that flowers are capable not only of recording a single moment of departure, but also of swallowing time, of recasting it on a different scale.

Mikhail Vrubel (left), Vladimir von Derviz and Valentin Serov in their youth. St. Petersburg. 1883

Photograph. © Manuscript Department, Russian Museum. Fund 160. Inventory 1. Item 363. Sheet 6

A metaphorical comparison of Vrubel’s art with some rare flower could be seen in much of what was written around the time of his death, as well as in earlier criticism. Where Nicholas Roerich’s comparison of Vrubel’s work to a “mysterious blue flower”[13] was laconic and full of Symbolistic meaning, a reviewer of the “Mir Iskusstva” [World of Art] exhibitions was more expansive: “Vrubel [...] has blossomed entirely from within himself. This is no rose, no lily-of-the-valley, no chrysanthemum, nor any new variant of them, but some entirely new flower, as yet unnamed and uncategorised in academic herbariums, the very aspect, the very unusualness of which will long yet produce on the public the unnerving impression of a ghost or vision.”[14]

Of course, neither Vrubel himself, nor the dynamic fantasy of his flowers and ornamentation were ghostly, just as the flowers of the funeral wreath failed to disappear without a trace. Every other newspaper obituary noted that “the deceased’s coffin was surrounded by a mass of fresh flowers and wreaths from various artistic organisations, admirers, and relations. Among the wreaths, those that especially stood out were ones from the Imperial Academy of Arts, the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, students of the Academy of Arts, the spring exhibition, the Kuindzhi Society, the Union of Russian Artists, various groups of students from the Academy of Arts, relatives, friends and many others.”15 Other more informal statements regarding how Vrubel’s funeral flowers decorated his last day on Earth have also survived. On April 6, Aleksandra Botkina (the daughter of Pavel Tretyakov) wrote to Ilya Ostroukhov, likely in relation to the much praised wreath from the Tretyakov Gallery: “And you know, it did look very beautiful and appropriate. Serov had breakfast here that day and was also very cheered by my idea about the wreath. They say that it was one of the most beautiful. Let’s suppose so, for I can do no wrong!!! [...] Students predominated, from the Academy of Arts, from the Zvantseva School (Baksta), as well as members of the Union of R[ussian] A[rtists]. There were multitudes of them and they took it in turns to act as pallbearers. Benois, the Lanceray brothers, and Dobuzhinsky carried the coffin along Voznesensky Prospekt. It was very well done. At the graveyard, at the edge, there was a mountain of wreaths, next to which Blok gave the address, skylarks pouring out their hearts overhead. Vrubel himself was so slight, dried out and, no doubt, light that they carried the coffin as though it were that of a young girl.”[16] Serov laconically expressed a very similar impression in a letter to his wife, saying that the artist’s face in the coffin, “now resembles very much that of the former, young Vrubel”17: “We buried Vrubel yesterday. The funeral went well - not luxurious, but imbued with a good, warm emotion.

A fair amount of people came, and those who came, came sincerely.”[18] Many of Vrubel’s contemporaries in the Silver Age who attended the artist’s funeral without having known him personally were brought there by an overwhelming sense of inner interconnection with the creative personality of the artist. Vrubel had overcome the constraints of man’s earthly preserve in his art and these mourners were keenly aware of the way in which the spiritual vibrations of the era pulsed in the patterns of his visual-poetic reality. Alexander Blok gave a subjectively profound and tragically significant speech on the “navy-lilac” worlds created by Vrubel[19], despite not being personally acquainted with the artist. Another poet of the Art Nouveau period, Sergei Gorodetsky, published a short but psychologically encompassing article in “Zolotoye Runo” (“The Golden Fleece”), a Symbolist journal that had recognised Vrubel as leader of the new art for the entire span of its existence. Gorodetsky wrote: “I heard that Vrubel had died at the close of the day, as the sun sank towards the horizon, and I went to visit him, although I had never seen him in life and had never been personally acquainted with him. It was the final requiem before the funeral cortege. People were already milling around the steps and making small talk. The church was empty and he lay in the small coffin, surrounded by a handful of close relatives. The first thing that struck one was that it was a child lying there. The second was that the child-like figure of Vrubel had been tormented, in the way that beatific humility was tormented in the Middle Ages and earlier, both stupidly and cruelly. The third was the shining face of a genius, an eternal joy [...] I placed a lily, proud and pure like those held by the angels at the Annunciation in the sacred coffin and gratefully kissed the small, marble hands, bereft of warmth and clasped eternally together, for myself and for all those who had mocked him.”[20]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Graveside Lamentation. 1884

Oil on canvas. 218 × 152 cm. Arcosolium niche. Narthex. St. Cyrill’s Church, Kyiv, Ukraine

Why have we begun a discussion of flowers and ornamentation in Vrubel’s art with the academic experience (metaphysical in nature) of the clash of contemporaneity with echoes of the past in the form of petals taken from graveside wreaths? Why have we gone from summing up the eternal artistic works of the master to trying to fit them into the ornamental line of funereal column inches and final reminiscences that surrounded Vrubel in the first days of April 1910?

The envelope with its delicate herbarium, which was discovered in the Manuscript Department of the Russian Museum is a sort of harbinger of time, a visual-poetic reflection of emotions which, one way or another, were always present in the patterned spaces of Vrubel’s works. For all the diversity of composition, researchers and viewers alike have noted more than once that Vrubel’s flowers possess some sort of timeless vital energy that bewitches with its artistic content.[21] The lyrical concentration of meanings present in his roses, lilacs, azaleas, bell flowers, dog roses, cornflowers, and other representatives of the plant kingdom exerts its effect via their figurative forms to send those who look upon them to a space of meditative metaphors. It is exactly as a sort of visual metaphor that we may look upon the idea of a “flower”, symbolising in the graphic beauty of its form the flow of time between the beginning and the end.

In the context of Vrubel’s poetics, beauty is spiritually saturated even in its most usual and, it would seem, familiar incarnations. Words like fantasy, fairy-tale or cosmogony in relation to the decorative and ornamental characteristics of the artist’s works are far from random, run-of-the-mill “epithets”, but rather verbal orientation markers of the utmost importance. On the semantic level, they permit us to penetrate the artist’s world of visual-poetic transformations: the metamorphosis to which Vrubel was inspired by contemplation of a real flower[22] or leaves[23], the flaming drops of sunset[24], pouring flaming wax upon pond lilies[25] or the crystal flowering of mountain ridges, by the radiant, pearly inner valves of a shell26, hidden in the sorrel, mother-of-peal waves of the outer “bark”, all of which inspired Vrubel to a contemplation of the eternal laws of nature, to a reflection of the spiritual gauging of life via the language given to him by art.

Watercolour, lead pencil on paper. 24 × 15.8 cm.

© Kyiv Art Gallery National Museum, Ukraine. Previously kept in E. Bunge collection, Kyiv

The decorative compositional elements in Vrubel’s art were originally given an aesthetically multi-dimensional scale, which the artist saw as being comparable with the same understanding of beauty, idealistic in spirit, with which the art of Byzantium and the Renaissance is imbued. The fact that Vrubel understood and transformed, in his own stylistic context, the expressive techniques of the mosaics, frescoes and icons of Kyiv, Venice and Ravenna in synthesis with the artistic inheritance of the Italian Renaissance masters (Giovanni Bellini, Raphael, Tintoretto, Titian, Paolo Veronese) is clearest of all in the works of his Kyiv period (April surrounding Christ Pantocrator (the central cupola of Kyiv’s 10th-century St. Sophia Cathedral; 1884); in the ornaments (1888-1889) and sketches for an unrealised composition that was to have adorned St. Volodymir’s Cathedral (1887, Kyiv Art Gallery).

Christ Pantocrator (Christ Almighty) surrounded by angels.

The central dome of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv Mosaics. 11th century. Of the four Archangels, only one is mosaic (the figure in a blue chiton). The others were finished by Mikhail Vrubel in the course of restoration using oil paints (1884)..

Oil on plaster. The vault of the central dome. St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, Ukraine

Oil on plaster. The vault of the central dome. St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, Ukraine

There are nearly no creations of Christian art from which flowers and ornaments are absent and, in spite of their tremulously brittle existence (“As for man, his days are as grass: as a flower of the field, so he flour- isheth”)[27], it is precisely in the liturgically lit space that every blade of grass and every pattern is invested with memory of the Godhead. In turn, it was precisely that dimension of beauty, which is a reflection of the reality of God, that was absorbed by Vrubel at the very beginning of the process in which his creative language was formed. Although history does not love conjecture, we do wonder all the same whether Vrubel would have become the artist he did were it not for the transformative experience of the spiritual awakening that took him by storm via Byzantine and Old Russian art and filled his intuitive expectation of the illusional and “of the pure and stylistic beauty in art”[28] with an understanding of the spiritual scale of the metaphor present in any allegory, including that of a flower imbued with life.

Vrubel’s “strangely brave flowers”[29], varying in the degree of their stylisation and their genre - still-life, decorative panel, ornaments, sketches for compositions on majolicaware, background motifs for complex compositions - are united by one common characteristic: they are potentially “substantive”, capable of weaving their own psychological links with the external world by constructing around themselves (on page or on canvas) an original idealistic space. The metamorphosis of Vrubel’s ontological insights, their translation into a visual language, takes place in no more and no less than a “Byzantine” range, as is evident in the equivalence of metaphors based on a flower, a landscape or the contours of a face when the subject is the mystery of how spiritual life is expressed externally - intermittent, as it is earthly, but, at the same time, eternal. It is precisely the shining infinity of eternal life that “resurrects” the airy mass of roses, lit as if from within, in one of Vrubel’s sketches for St. Volodymir’s Cathedral (“Resurrection: Triptych with Two Angelic Figures Above Sleeping Warriors”, 1887, Kyiv Art Gallery). The artist achieves a symphonic effect with the composition’s elements via the absolute coherence of every inner motif in their striving to express the image’s spiritual keynote: resurrection from the dead. Every twist of the floral pattern, every spatial geometry transfixed by the Holy Spirit, the very colouristic vibrations of the watercolour’s texture, are all constructed in unison with the pathetic dynamic of spiritual reality. It is exactly for this reason that Vrubel’s flowers are, for all their abstract basis, lacking in any merely speculative conventionality: the rays and waves of the energy in his artistic thought always had a semantic centre.

Mikhail VRUBEL. The composition “Pentecost”, crowning the image of “Emperor Cosmos.” 1884.

Oil on plaster. The vaults of the choirs of St. Cyrill’s Church, Kyiv, Ukraine. Vrubel strives to produce a mosaic effect using oils, as he did at St. Sophia Cathedral.

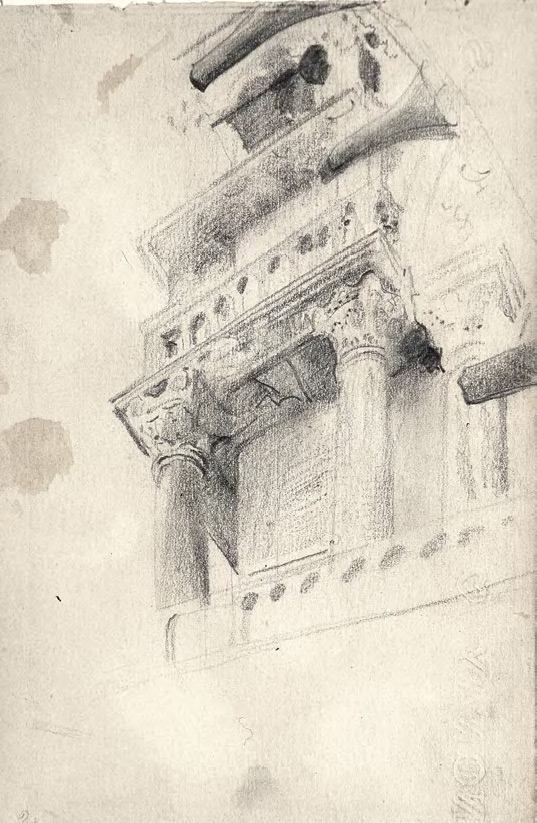

Of course, “colouristic” detail never dominated over the semantic wholeness of the artist’s figurative compositions, the synthesis of which expressed the ultimate symbolic points and main narrative lines. However, even the powerful emotional fervour of religious scenes is depicted by Vrubel with a decorative allegoricality. Such, for example, is the case with the movement within the composition “Pentecost” (1884) on the basket-handle arch of St. Cyrill’s Church, from the figures making up the main scene to the culminatory image of the “Emperor Cosmos” (a symbol in Byzantine iconography for the part of humanity that will receive the light of Christ’s teaching from the enlightened Apostles). The basis of this movement is an ornamental pattern30 comprised of blue, gold, pink, emerald and white geometric planes: patterned carpets beneath the Apostles’ feet, the energy-charged arcs of descending divine grace, “zig-zag” decorative ribbons, the rhythms of which echo with those of the drawings of waves stylised as triangles, the latter being one of the abstract motifs we can find in the ancient mosaics of St. Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv or the Basilica di Saint’ Apollinare in Classe (second quarter of the 6th century, Ravenna). Vrubel not only thoroughly studied Byzantine art, embarking on a trip to Venice to that end (November 1884-April 1885)31, but also understood it in a professional sense: “The main defect in the work of modern artists who attempt to resurrect the Byzantine style is that the folds of clothing, to which the Byzantines dedicated such ingenuity, are replaced by mere sheets. The concept of relief is an alien one to Byzantine art - the whole aim is, in fact, to emphasise the flatness of a wall with the help of ornamental forms.”[32] In his art, Vrubel also surmounted the need for material relief, transforming it into an ideal artistic image of monumental resonance. He mastered the synthesis of the individual and the universal that lay at the basis of Byzantine art and that, in turn, allowed him to remain focused on the central aim of expressing the life of the Spirit, even as he wove his decorative patterns. At the same time, the aesthetics of the outer world were not rejected, but rather used to enrich this stylistic endeavour with real-life observations. It is no coincidence that Vrubel introduces into his religious images certain motifs that preoccupied his own soul and “eye”, motifs such as the roses that twine around the throne of the Mother of God in the altar icon of St. Cyrill’s Church.

Work on the sketches carried out 1888-1889. Stepan Yaremich and Leon Kowalski both helped the artist in the practical realisation of his concept.

This original discovery of the “Byzantine” laws of decorative monumentalism (that is, the universal bases for the organisation of the life rhythms of even small forms) also found a concrete embodiment in the artist’s ornamental developments. The organic plasticity of the decorative motifs Vrubel developed for St. Volodymir’s Cathedral - the thick golden waves of wheat, the tresses of which are framed now by blue bell-flowers, now by the dangling “wings” of pink poppy petals, the inner blue eyes of which harmonise with the spotted azure of peacock tails and with the faces of angels, alternating with round patterns, together forming an ornamental ribbon leading upwards - all this, on an individual level, is a continuation of the exultant visual chants of Byzantium. As Nikolai Prakhov bears witness, one of the impulses acting on Vrubel’s fantasy as he worked on these compositions was that of the mosaics of Ravenna33, the spiritual content of which Vrubel was able to enter into so deeply that even that arch-critic of the artist’s decadent style Vladimir Stasov, who had devoted many years to the study of ancient ornaments, noted the penetrating historical intuition of the artists and, on that basis, mistakenly attributed them to Viktor Vasnetsov. We will not dwell here on these “art-criticism” red herrings that Stasov’s views sometimes lead him to, especially given that we have just had a chance34 to examine a similar misapprehension and Vrubel’s protest against it.35 In this instance, what is of most interest for us is the demonstration of the natural balance between Vrubel’s personal fantasy and his artistic and historical intuition: Vrubel derived new artistic harmonies from real-life impressions of life and nature. It is worth noting that Vrubel himself, notwithstanding the spiritual expressiveness of his decorative ornaments for St. Volodymir’s Cathedral, the perfection of which was noted by many contemporaries (among them Alexandre Benois and Vasily Polenov), remained unhappy with his work. “I cannot recall without disappointment my decorative exertions”36, he wrote. For Vrubel, who was in constant “search of the ideal”37 in art, apprehensions such as these characterise the values of the artist, who had “become inebriated to the point of self-torment”38 (as he wrote to his sister).

Work on the sketches carried out 1888-1889. Stepan Yaremich and Leon Kowalski both helped the artist in the practical realisation of his concept.

Work on the sketches carried out 1888-1889. Stepan Yaremich and Leon Kowalski both helped the artist in the practical realisation of his concept.

It is also worth noting that, in the Kyiv period, Vrubel’s decorative-monumental fantasy found expression not only in religious art, but also in secular art. Fragments of murals by Vrubel were discovered and restored in the “Dutch Kitchen” during renovations at the house of the Kyiv collector Bogdan Khanenko[39] in the 1990s. The interiors of Khanenko’s house, which took shape in 1889-1890, reflect the popular contemporary fascination with a range of historical periods, which explains the inclusion in the overall design of elements stylised in the spirit of an Italian palazzo on the one hand, and of Gothic features on the other. Vrubel’s spiritually expressive flowers initially covered the whole space of the dining-room ceiling in their energetic whirlwind. However, the contrast with the more conventional decorations of other rooms was not to the taste of the client and they were largely painted over with golden lions and griffons, leaving only the central part of the pattern unobscured, along with the Khanenko family crest (three towers with a star above them and a crowned knight’s helmet, beneath a star and ostrich feather). At the time of writing, another small fragment of the floral pattern has been cleaned by restorers (likely depicting the downy head of a pink tulip), which had previously been obscured by the ancient power symbol. Furthermore, according to the latest research by academics in Kyiv[40], Vrubel carried out a sketch for another ornamental frieze in Kyiv in the spring of 1889, this time for the space above the main stairway, which was carried out by a group of young artists under his direction (it is reliably known that among them was Stepan Yaremich). The ornamental frieze consisted of stylised lake-side flowers (there is something “reed-like” in the mood of the stretched-out, sheared leaves, bringing to mind transformed leaves of water lilies) and was adorned with a not-entirely-faithful quote from the third part of Dante’s “Divine Comedy” (“La divina commedia”) entitled Paradise (Canto IV, 1-3): INTRO DUO CIBI DISTANTI E MOVENTI DUMMODO PRIMA S MORRIA DI FAME CHE LIBERUOM L’UN RECA- TO AI DENTI. CD.[41]

Bogdan and Varvara Khanenko

© National Museum of Arts in Kyiv, Ukraine

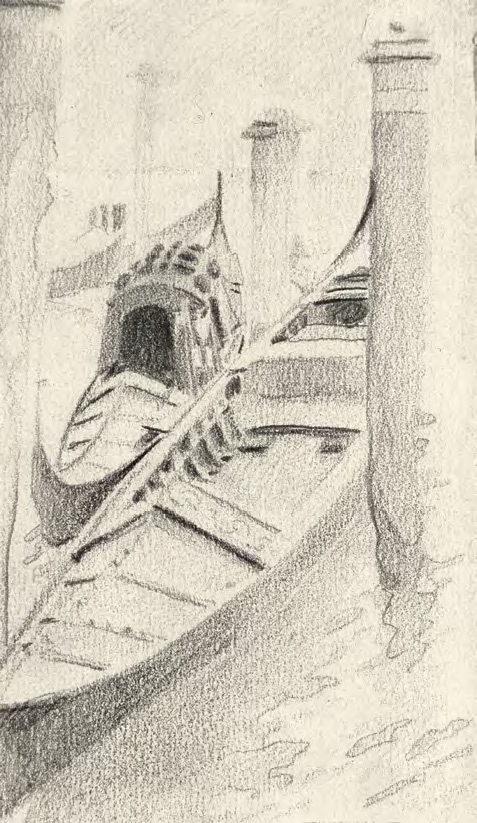

Vrubel’s capacity for monologues of genius was possibly the reason for the twists of fate suffered by many of his works, which were criticised at the time for an eccentric, decadent distortion of nature. However, the artist had no quarrel with nature, nor did he ever seek to remake it, as even contemporaries who knew the artist well sometimes claimed (admittedly, in approving tones)[42]. Vrubel knew how to perceive physical forms via his own inner world - via a “spiritual prism”[43], as the artist himself put it - thus discovering the hidden, irrational potential of materials. One objective piece of evidence showing that the natural impulse was an important source of Vrubel’s iconographic poetics are the albums, whole or scattered, in which he made life sketches of faces, figures, flowers and architectural motifs (for example, of Byzantine columns), as well as chamber pieces depicting his “inner” world, the tonal ornaments of which demonstrate a link with the artist’s late graphic work (see “Album 1884-1885”[44] and “Venice Album”, late 1884-188545, both in the Kyiv Art Gallery).

Lead pencil on paper mounted on paper. Image: 14 × 8.3 cm; sheet: 17 × 11.8 cm

© Kyiv Art Gallery National Museum, Ukraine

Vrubel’s creative fantasy rested on genuine couplings of spiritual insights with concretely biographical elements. These latter include not only events from his own personal life but also the literature he read, the landscapes that surrounded him and the photographs he used when creating his artworks: “no hand, no eye, no patience could ever objectify a scene like a camera does - investigate all this lively and truthful material with your spiritual prism: the camera will only fray itself out on the subject’s opaque reliefs, it has dimmed, too jealously guarded.”[46]

Even judging by the evidence that has survived for academic analysis, it is clear that Vrubel had a large collection of photographs that served as a real support to his imagination as it broke through into the transcendental field of ornamental allegory. Vrubel’s collection included landscapes and shots of various works of art, the most significant part of which were sheets from Ivan Barshchevsky’s album of “Old Russian Architecture and Applied Art,” which was published over the course of 15 years (1881-1896). A comparative analysis of a number of Vrubel’s works and some of Barshchevsky’s photographs belonging to him, such as the kokoshnik headdress “The Swan Princess” (1900, Tretyakov Gallery) or Sheet No. 515 featuring illustrations of ancient pectoral icons and necklaces (Manuscript Department, Russian Museum, fund 34, inventory 1, item 85, sheet 6[47]), permits us to conclude that the artist’s interest in Russian fairy-tale themes found serious support of its iconographic basis in photographs which objectively showed the architectural and applied-art patterns of the past. Vrubel’s collection included, for example, shots of the interiors of the Kremlin’s Terem Palace, Palace of Facets and Patriarch’s Palace; the western door of the Candlemas Church of the Borisoglebsky Monastery near Rostov; the entrance to the Trinity Cathedral of the Ipatievsky Monastery in Kostroma; Vologda woven lacework, ancient church ornaments, helmets and other items.[48] It is more likely than not that Vrubel knew Barshchevsky personally - they could have met during Vrubel’s summer visit to the Talashkino estate belonging to Princess Maria Tenisheva in 1899, where Barshchevksy had been contributing to the foundation of artistic workshops and a museum since 1897.

Venetian façade. Photograph from Mikhail Vrubel’s personal collection.

© Manuscript Department, Russian Museum. Fund 34. Inventory 1. Item 86. Sheet 13

Of course, this instance of the special attention that Vrubel paid to the poetics of patterns in old Russian art is just one of many possible examples that demonstrate the peculiarities of his work on the plastic language of images, in which the verisimilitude of his fantastical instrumentation was enhanced by the introduction of real-life details into its patterns. A special place in this context is occupied by Vrubel’s study of the decorative and ornamental essence of Venice, the monumental

and architectural structure of which so resembles a stone lacework of fagades (Manuscript Department, Russian Museum, fund 34, inventory 1, item 86, sheet 13). Vrubel’s irrealistic improvisations were also given an authentic graphic impulse by pieces of art photographed from unusual angles, as if casting metaphysical shadows (Manuscript Department, Russian Museum, fund 34, inventory 1, item 88, sheet 3), as well as fabrics decorated in original patterns (Chinese and Indian), shawls, Persian carpets, antique objects and everyday objects encircled in silence (a faceted drinking glass, an empty bed, a cloistered plaid) and, finally, creatures of the natural world. Among the latter, we cannot fail to mention the mother-of-pearl shell (a Haliotis, or ear shell) in Vrubel’s collection, which served as the iconographic source of his “Pearls”. We can see the justification, therefore, of the repeated relaying in contemporary memoirs of the artist’s conception of real life as a tuning fork within illusory images: “When you are planning on painting something fantastical - a painting, or a portrait, for portraits can also be painted on the fantastical rather than the realistic plane - always begin with a little piece that you paint entirely realistically. [...] This plays a role akin to that of a tuning fork in choral singing - without it, your fantasia will be bland and stilted, and most certainly not fantastical.”[49]

Elbrus and the ridge between Azau and Donguzorun from a height of 7,500 ft (2,286 m). Photograph from Mikhail Vrubel’s personal collection.

© Manuscript Department, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg. Fund 34. Inventory 1. Item 84. Sheet 18

Mikhail VRUBEL. Demon’s Head. 1890-1891

Illustration for Mikhail Lermontov’s poem “Demon”. Black watercolour, whitewash on cardboard. 23 × 36 cm (delineated image)

© Kyiv Art Gallery National Museum, Ukraine

Among the sources in which Vrubel found stable touchstones upon which to base his formal metamorphoses were “pieces” of real landscape, places he himself had visited in person or appreciated via photographs. In this context, a series of photographs with mountain views of the Caucuses and Crimea that were used by the artist while searching for a spatial pattern for his Demons are of special interest. Furthermore, he had recourse to these images in both his early (as we know from the reminiscences of Valentin Serov, recorded by Stepan Yaremich, from 1885[50]) and late[51] periods (paint stains can still be seen on certain photographs with views of Kazbek and Elbrus seen from the ridge between Azau and Donguzorun (Manuscript Department, Russian Museum, fund 34, inventory 1, item 84, sheet 19 and sheet 18 obverse). More unexpected clues to an understanding of even the boldest of Vrubel’s transformations of reality into a quickening, mythopoeic actuality can be garnered from certain photographs of birch groves that belonged to the artist (Manuscript Department, Russian Museum, fund 34, inventory 1, item 86, sheets 2 and 4; by way of comparison, we can think of “Pan”, 1899, Tretyakov Gallery). The photographic landscapes that make up Vrubel’s collection include both amateur and professional shots. For example, elegiac photographs of snowy birch alleys and ‘staged’ shots of village workdays include the works of Aleksei Mazurin. The path by which a real natural motif that had managed to touch the artist was transformed into a multidimensional pattern of image and metaphor is further revealed by a series of photographs of the garden of a cottage owned by the Ge family (Manuscript Department, Russian Museum, fund 34, inventory 1, item 84, sheets 1, 13, 15) that were taken for Vrubel (who had bought a camera specially for the purpose) by the artist Viktor Zamerailo in May 1901 while the artist himself was working on the second version of “Lilac” (unfinished, 1901, Tretyakov Gallery).

![Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel “imbibing” lilac. [1901]](https://www.tg-m.ru/img/mag/2021/3pr/art_72pr_01_113.jpg)

Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel “imbibing” lilac. [1901]

Photograph from Mikhail Vrubel’s personal collection. Photograph by Viktor Zamerailo. © Manuscript Department, Russian Museum, St. Petersburg. Fund 34. Inventory 1. Item 84. Sheet 15

In the context of these rather cerebral patterns, it is worth noting that, on a metaphorical level, the lilacs in Vrubel’s art are related most of all with lyricism (it is entirely understandable why the female figure in the paintings may have been identified in the artist’s imagination with Pushkin’s Tatiana[52]). As a hidden source of lyrical harmony, the lilac is always there in Vrubel’s works, even as a formally implicit or transparent presence. Many of the emotional and notional connotations of this unseen motif are woven together in the semantic totality of the unfinished painting “After the Concert. Fireside Portrait of Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel” (1905, Tretyakov Gallery), if one knows the intentions of the artist. “My husband is working very hard and very fruitfully, and has begun a new shell... [...] Furthermore, he is painting my portrait on a very large canvas. In it, I am wearing an elegant concert dress, there is a basket of flowers behind me and on the floor in front of me are scattered various scores, including that of Rachmaninov’s ‘Lilac,’ with which I am enchanting St. Petersburg,”[53] as Zabela-Vrubel wrote (she was the first performer of this, one of Rachmaninov’s “quietest”[54] romances). It is precisely the barely perceptible harmony between the “fragrant shadow” of lilac, the flames dancing like lilies in the fireplace and the smoky-floral flower of Zabela’s concert dress, which was based on Vrubel’s sketches, that creates the original, secretive pattern in whose polyphony begins to pulse the psychologically accurate life of the artistic image.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Lilac. Sketch for eponymous painting (1900, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow).

Oil on board. 18.7 × 23 cm. © Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Vrubel’s interest in photography as the basis of further visual-decorative explorations aimed at the stylisation of multidimensional reality into textured ornamental patterns can be seen even before his work on the “Lilacs” and “Demon”. Vrubel’s ability to uncover original links - leading associatively to the reality of different images - between certain shots of particular themes is, in fact, apparent from the mid 1880s on. While he was considering the composition of “Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane” (1887, Tretyakov Gallery), the lower part of which is smothered in a primaeval mist of lilies whose slow movement resembles the waves of the sea, Vrubel wrote to his sister: “I have definitely decided to paint Christ: fate has presented me with wonderful material in the shape of three photographs of a wonderfully lit hillock with a bunch of aloe growing among blindingly white stones and near-black clumps of burnt grass... [...] You should also know that, in the photograph, the bright sun gives the remarkable illusion of being a midnight moon.”[55] The transformation of funeral greenery into flowers that sparkle with a quiet liveliness, along with the moon-like halo around the head of Christ in the context of the surviving lines of Vrubel’s letter, permit us to discover factually as well as certainly the traces of the poetic metaphoricity that lay at the heart of his artistic method and combined in a single whole both feeling and thought, along with its visual (illusory-physical) embodiment.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane. 1887

Charcoal on paper mounted on cardboard. 140.5 × 52.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The synthetic poetic-metaphoric approach that lay behind the unpredictable logic of the artist’s thinking and was responsible for the organically developed Symbolist approach to an understanding of the role of the image in art, was also largely the source of the perturbation which agitated contemporaries and accompanied Vrubel’s art in nearly every period. “Is he not a decadent?”[56] was the thought of the composer Yanovsky after his first meeting with the artist whose art he soon became a great fan of. In his memoirs, Yanovsky also left a detailed description of the garden of the Ge family farm, the mysterious pond, lilacs, roses[57], and other flowers of which kept Vrubel inspired over the course of more than one artwork, in particular the cycle of decorative panels for Savva Morozov’s mansion “Times of the Day” (1897-1898) and “Morning” (1897, Russian Museum), which originally formed a part of the series), “Lilacs” (1900 and 1901, both Tretyakov Gallery), and “At Nightfall” (1900, Tretyakov Gallery). In 1897, Yanovsky compared his impressions of the estate at two different times: “I walked around the garden and visited the tomb of Nikolai Ge. [...] The pond was, as ever, full of croaking frogs and whispering reeds. [...] The hot sun painted the alley and paths in a pink colour as it penetrated the greenery. By the open verandah, thick masses of flox were scattered around, red hollyhocks blazed like fiery disks against dark foliage and, a little further on, one could catch the fine scent of innumerable roses. Directly opposite the verandah and on the very edge of the pond stood a giant old lime tree and, under it, a bench”[58]. It was on exactly that bench that Vrubel most often chose to sit[59] or lie, gazing at the sky[60] and thinking about his next paintings, wrote Yaremich, who was, at that time, also living at the farm.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Lilac. 1900

Oil on canvas. 160 × 177 cm. © Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

In the period covered by Yanovsky’s memoirs (July- August 1897), Vrubel was pondering the figurative rhythm of the relationship between times of the day and working on the cycle of decorative panels “Times of the Day” for Savva Morozov’s mansion (the architect of which was Fyodor Schechtel). In the symphonically overgrown patterns of his composition, Vrubel was seeking to unite in a natural way a mesh of the life- imbued organic world with the movement of time as it aesthetically transforms images of nature and discovers in the world of physically real objects something irreal, half-fantastical and talking in the language of illusions. This visual metaphoricity of the panels, built on the basis of musical principles and expressed in a synthesis of decorative and ornamental methods and landscape impressions, was not immediately understood, even by musicians, due to its emotional and semantic multidimensionality. Thus, for example, Yanovsky wrote: “gazing at ‘Evening,’ at first, I understood nothing. I had been raised on the Old Masters and was still under the influence of the works of Ge, which had once so enchanted me, so I was lost at the sight of such an unusual - for me - manner of painting. The trees struck me as being strange, depicted somehow superficially, without details, and strange too was the way they lay on the background of the sky somehow ornamentally, and strange also the rays of light, the very colouring, and the female figure with her finger to her lips and enormous eyes. The flowers too, with their wide petals, the grass, and the inexplicable creature lurking in the corner. I was at a loss and turned to Vrubel. With regard to the female figure, he explained that it was a fairy, saying to the flowers ‘quiet down, go to sleep,’ and of the inexplicable creature he said, ‘that is a fairy tale.’ It was only afterwards that I entered into the full delight of Vrubel’s art, his wonderful fairy tale of Russian nature, learnt to see all the incomprehensible charm of his unique and astonishing mastery, and felt, if I may so express myself, the tender music of his creations. [...] ‘What composer does this piece remind you of?’ asked Vrubel. I could think of nothing better to say than Rebikov (who was also then considered a ‘decadent’). ‘Well, now, that’s a fine comparison to make,’ countered Vrubel. Then I thought of Schumann’s ‘Traumerei’ [‘Dreaming’ - O.D.]. ‘Now that’s more like it’[61].”[62]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Princess of Dreams. 1896

Oil on canvas. 750 × 1400 cm. © Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The music of Vrubel’s painterly language was difficult to place in the usual norms of visual harmony: it was a genuine lack of understanding on the one hand and, on the other, intentional (collective) malignity largely (one suspects) born of an apprehension of the dangerous unpredictability with which the artist’s poetics developed, and of the artist’s gift for metaphor. See, for example, the words of Sergei Vinogradov written to Yegor Khruslov on Vrubel’s patterned monumental panels “Princess of Dreams” (1896, Tretyakov Gallery) and “Mikula Selyaninovich” (1896, location unknown; sketch in the Tretyakov Gallery) not being permitted entry to the official exhibition of the Arts Section of the All Russia Industrial and Art Exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod (1896): “Is it true that Vrubel’s panel has been refused entry? I am glad to hear it, and to tell the truth, I think the dethronement of the ‘genius’ entirely justified. I cannot tear myself away from ‘News of the Day’.”[63]

Yet all the same, Vrubel’s ornamental poetry, which reached a sometimes chaotic expressiveness in, for example, “Demon Downcast” (1902, Tretyakov Gallery), in which the lacework of mountain landscape, wings and broken body give rise to a new visual accord of spiritual suffering, was accepted by society (or at least tolerated) earlier than, for example, Baudelaire’s “Les Fleurs du Mal” (1857), which was officially rehabilitated by France’s Court of Cassation only in May 1949, after its Symbolist literary depth had been neglected for 92 years.

When considering Vrubel’s interrelation with nature one cannot, of course, fail to touch upon the following question of principal importance in that context: the nature-philosophy of Symbolism, the associative poetic logic of which was expressed in the uniqueness of the artist’s figurative thinking. By synthesising the real and the spiritual, Vrubel managed to insert an inner premonition of unexpressed meanings into the structure of his canvases and graphic works, which, via Symbolism, influenced the modification of forms into abstraction. “As ‘technique’ is but the ability to see, so ‘creativity’ is but the ability to feel deeply,”[64] to quote Vrubel’s own thoughts. This intuitive perception of material reality as a motif pregnant with the potential for artistic development, the creative metamorphosis of which creates the illusion of new life, was what lay at the foundations of Vrubel’s decorative “sprawling imagination”[65], about which Vasily Milioti, a member the “Blue Rose” group of Moscow Symbolists, wrote as of “a revolution in the methods of addressing decorative planes. It is enough to say that it already contained the seeds of Cubism, but without reaching the absurd, thanks to the effective influence of his overwhelming sense of beauty.”[66]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Page with demonstrative stylisations. Late 19th - early 20th century

Pencil on paper. 56.3 × 45.1 cm. © Ivanovo Regional Art Museum

Milioti’s opinion can also be applied to Vrubel’s flowers. Gazing at the elaboration of ornamental textures in the artist’s painting and graphic works, one comes to understand that his flowers are at once flower structures and flower poems, multi-dimensional in their graphic content. This can be confirmed with a rare level of academic certainty with reference to the small-format drawings that once formed part of Savva Mamontov’s collection and are currently stored in the Museum of Applied Art of the Stroganov Academy of Industrial and Applied Arts (KP-2923). There is a symbolism here that is hard not to notice, for it was in precisely the Stroganov Academy that Vrubel spent three years (1898-1901) teaching a special course, The Stylisation of Flowers, which was introduced in autumn 1898 on the initiative of the academy’s director Nikolai Globa (with whom Vrubel became acquainted in Kyiv in the 1880s while they were contributing to the restoration works being carried out there). This pedagogical experience reveals in a most unexpected manner the conceptual (theoretical) aspect of Vrubel’s relation to flowers and ornaments, which, in turn, is inextricably linked to his overall artistic method, a synthesis of reality and the abstract. Himself a master of drawing from nature, he sought to first awaken in the consciousness of his students an awareness of the necessity of understanding the philosophical and poetic potentiality of an image during its creation, which was reflected in the annual introductory speech with which he began the series of lectures: ’’[Sheet 1] R[espected] S[irs], before addressing the prospect of our service to art and its forms, I would like to draw your attention to the ultimate aim which has been set for our activities. / - /. Any seeking implies the existence of an end point - an aim. The aim is the laurels that reward any seeking, when [Sheet 1 obverse] the quest is necessary and carried out single-mindedly. A unified plan is a crucial condition for reaching this end... [...] [Sheet 2] The world of reflections represents the spiritual necessity of this one end point, the unchanging selfhood of life which is, of course, not one [Sheets 2 and 2 obverse] among many, but the only one, which is prepared by every aspect of spiritual efforts with essential, insofar as is possible in our sea of possibilities, exclusivity. /[Sheet 3] In the global order of necessities, everything rushes towards the zenith of the one unchanging necessity of human[ity]. / [Sheet 4] How much more difficult would it be to contemplate this great aim of “necessity”, which is the essence of life, were it not for this unity of plan... [...] [Sheet 5] This “necessity” is eternal and infinite. It is an attribute of the ‘object’. The ‘subject’ is consciousness, splashing into this shoreless ocean and imagining that it can swallow it all up. Each gulp is a ‘possibility’. Consider how many such gulps there are.”[67]

To break through via a “gulp of possibility” to the sensation of the reality of temporal beauty as a phenomenon of spiritual necessity was, for Vrubel, the essence of an encounter with any creative process. It is unsurprising then that, in his paintings, even the small form of a flower can occasionally “swallow” an ocean, in a way that inadvertently calls to mind the “decadence” of “The Case of Wagner”, encapsulated by Friedrich Nietzsche - “we would be quite right to acclaim him [...] our greatest musical miniaturist, constantly cramming endless quantities of sweetness and meaning into the smallest space possible.”[68] That creative dynamic which involves non-observance of the usual hierarchies of scale, bringing together the grandiose and the innermost, the universal and the flower, is perceptible in Vrubel’s sketches from the collection that once belonged to Mamontov, presumably carried out in the 1890s.[69]

Ink, watercolour on paper. 8.5 × 8.5 cm. Moscow State

© Stroganov Academy of Design and Applied Arts Museum (Reproduced from: A. Troshchinskaya, The Works of M. Vrubel... P. 50, cat. 9)

These small, sometimes tiny miniatures reveal easily, yet in a structurally accurate manner, the architectonics of the universe via the micro-world of the flower. There is something of the harmony of the cosmos within the Vrubelesque geometry of meanings, whereby constructive elements or “archetypes” such as circles, ellipses, ovals and triangles unexpectedly transform into organic flower metaphors. From the point of view of poetics, the flower drawings from the Stroganov Academy’s collection could arbitrarily be divided into two groups based on their main emotional tint: nocturnal and diurnal.

Within the former group predominate blue flower structures, of a crimson-violet palette, whose evening modulations reveal themselves as if on the subdued twilit vermilion background of the sunset - for example, the “Gothic” blue cornflower from the cosmic bowl, which bursts a white spot of light amid the star-petals (KP-2923/13 [sheet]). In another cornflower (KP-2923/17 [sheet]), its architectonic composition renders the flower’s structure akin to some sort of monumental macrocosm (complete with its own moons in the form of grey cherries and clover-flattened earth, which - in the flower, as in the universe - exists with its own apparent logic of internal relations).

Ink, watercolour on paper. 8.7 × 8.5 cm. © Moscow State Stroganov Academy of Design and Applied Arts Museum. (Reproduced from: A. Troshchinskaya, The Works of M. Vrubel... P. 48, cat. 8)

The latter group is more joyful and bright. Orange- yellow and crimson-red along with coral-brown colours predominate, resonating with the playful rhythm of floral images from Aleksei Remizov’s fairy-tale “Colours”. For example, the sunny and unpredictably contoured brushstrokes of the yellow dandelions (KP-2923/34 [sheet]) or the radiant figures of “flying flowers” dancing above the green-blue garden, like the choirs of angels of the Old Masters, which figure on Sheet 9. Within this arbitrary daytime group, there are also flower universes in which the musical organisation, based on the rhythm of the synthesis of clearly defined elements, gives birth to new diminutive cosmoses (KP-2923/4 [sheet], KP-2923/28 [sheet]). Moreover, it is also worth noting that the subdued vermilion of the sunset is also a perceptible presence in the colouring of these miniatures. Among Vrubel’s 36 drawings,[70] there are also images in other registers. Remarkable for their lyrical potential, they sometimes shine silver, like frozen winter patterns, on the oval baluster of a vase (KP-2923/5 [sheet]), sometimes bloom as pink dog roses[71], like the tender and lovelorn daydreams of springtime in the ornamental stylised pattern of green branches (KP-2923/14 [sheet]).

Vrubel’s visual poetry of flowers is at once extremely metaphorical and functionally concrete, as in the case of the drawings we have just been discussing. Most of the miniatures from the former Mamontov collection mentioned above were sketches for majolica tiles that were actually made.[72] A whole range of drawings reveal Vrubel’s innate understanding of the logic of forms: the ornamental pattern is not arranged superficially, but rhythmically breathes life into the figurative structure, as if it were a natural part of the architectonics of the object itself. This characteristic is especially obvious in the sketches in which the artist is working with three-dimensional architectonic microforms (see, for example, the “little walking boot” for a stove cornice (KP-2923/10 [sheet]) or the drawings of an ornamental column, in which the blue pattern of fanning petal tails, all raised up in devotion, is reminiscent of ecstatic images of plants on Byzantine mosaics, KP-2923/33 [sheet]).

Ink, watercolour on paper. 4.3 × 3.7 cm (the image is cut out along the outline and glued to a thick paper sheet 8.3 × 7.6 cm).

© Moscow State Stroganov Academy of Design and Applied Arts Museum. (Reproduced from: A. Troshchinskaya, The Works of M. Vrubel... P. 66, cat. 24)

Ink, watercolour on paper. 5.5 × 4.5 cm (the image is cut out along the outline and glued to a thick paper sheet 8.5 × 9 cm).

© Moscow State Stroganov Academy of Design and Applied Arts Museum. (Reproduced from: A. Troshchinskaya, The Works of M. Vrubel... P. 68, cat. 26)

Speaking of the functional qualities of Vrubel’s floral poems, it is impossible to ignore one more unique example of his fantasy in the field of applied arts: the cloth flower from Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel’s theatrical dress, the appearance of which reminds one of a stylised (“from life”) water lily-camomile (undated, Russian Museum). The artist wrote of this surviving accessory from the wardrobe of the singer as the idol that had “illumined” his days (“idol mio, farfalla, allodola”[73]), which confirms once again that, even while using flowers for a practical “calling”, his lyrical and figurative impulses are in no way blocked.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Design for a comb. Illustration taken from “Mikhail Aleksandrovich Vrubel. Life and Work” by Stepan Yaremich (Moscow: Izdaniye I. Knebel, 1911, p. 125)

One can speak again of the interrelation between concrete material tasks (although of a different nature) and a graphic philosophy born unconsciously in the process of addressing them when discussing the series of studies (mostly watercolour) of flowers that Vrubel created while still in Kyiv. These little spur-of-the-moment visual poems composed of azaleas, orchids, peonies, painted daisies, periwinkles and other flora, which now form part of the collection of the National Art Gallery in Kyiv, were products of Vrubel’s “system”74 of teaching: “I sit and paint or draw, while the student watches; I find that this is the best way of showing what they need to see and how to convey it.”[75] It is precisely these private lessons, which he gave to Natalia Mantseva (nee Tarnovskaya) and E. von Bunge, the wife of a professor of Kyiv University, that were the motivation for the creation of a whole series of still-life masterpieces in the period from 1886 to 1888.*

* Captions in this publication indicate the initial location of these sketches.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Periwinkle. 1886-1888

Watercolour on paper mounted on cardboard. 16.6 × 12.2 cm

© Kyiv Art Gallery National Museum, Ukraine. Previously kept in N. Matsneva collection, Kyiv

Of course, there is much more we could have said on an objective level about the “Kyiv” flowers or the surviving parts of the Mamontov selection of sketches and their stylisations of floral motifs, as well as on the specific role of ornamental patterns in Vrubel’s majolica sculptures, and the theatrical costumes or the concert and everyday flower dresses belonging to Zabela- Vrubel. However, in this article, we would like to highlight those most important features that help us to understand, in an overall context, the artist’s general creative technique: Vrubel’s flower structures, flowing along the stem with poetic life, metaphorical not in their circularity, but, thanks to their astonishingly clear structuredness (see, for example, “Etude of a Flower on a Blue Background”, early 1890s, Museum of Applied Art of the Stroganov Academy of Industrial and Applied Arts, KP-2923/12 [sheet]). That is a characteristic we can identify not only in the drawings we have just discussed, but in Vrubel’s work in general, in which the floral and ornamental elements declare themselves to be one of the leading bases in the formation of the artistic image as a whole.

In poetry, metaphor is the basic premise of metamorphosis. It provokes a movement in which one form comes to resemble another, expanding the meaning of the visible. This is also what we see in Vrubel’s work, the basis of whose artistic thinking is the perception of forms as patterns, patterns that are psychologically rooted. At times, it seems as if Vrubel notices only contours and lines, but, in the end, an incredibly capacious image is the result, able to transform a flower into a face, a shell, the cosmos or a bed rumpled by insomnia into a tragic fracture in spiritual regularity, the life rhythm of which has begun a decline.

Vivid evidence of the ambiguous, at times straightforwardly indignant, reception that contemporaries greeted such artistic thinking has been preserved in an unpublished manuscript written by Vladimir Stanyukovich about Vrubel. In this interestingly subjective monograph, which is remarkable both for its accurate generalisations and the traces of contradictory interpretations that had not yet established themselves in mainstream understanding, Stanyukovich writes about the bewilderment people felt on first becoming acquainted with Vrubel’s art. From his description, it is clear that it was precisely the elusive patterns, refined to the point of chaos, that raised peoples’ hackles: “I remember, as a youth, my first, almost offended, impressions of his illustrations to ‘The Demon’, appearing in a luxurious (by the standards of the time) edition of Lermontov’s works (1891). Next to the calm and accessible illustrations of the other artists, their difficult and arbitrary images and techniques stood out like a sore thumb. ‘Whose drawings are these? What sort of nonsense are they?’ My contemporaries and I were filled with indignation, and the name Vrubel became synonymous for us with the impudence of the decadents. / This figure of a strange being in a woman’s dress decorated with lace, with its tortuously malicious face framed by waves of black curls; this formless architecture of wings spread wide to form sullen storm clouds; these dancing and lacerating brushstrokes, now forming the patterns of a carpet, now unexpected figures - all this was unusual and vexingly confusing. It was even difficult to make out the artist’s dark, galloping figures on the motley canvas, and it seemed pointless to study them carefully... [...] The tortuous dance of daubs vexed and mocked the created dream and so we rejected these ‘ridiculous and arbitrary illustrations’. / From that time on, I have never again come across the book, although I have never been able to forget ‘The Demon’ wearing a decollete dress, his tortured smile, piercing eyes, the fissures of his hands, the gloomy storm clouds of wings, and the near-audible patterns of the carpets. For some unknown reason, the ‘ridiculous arbitrary’ image struck me and became an unforgettable part of my life.”[76]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Tamara and the Demon. “Don’t weep child, don’t weep in vain.” Illustration for the poem “Demon.” 1890-1891

Black watercolour, whitewash, scratching on paper mounted on cardboard. 96 × 65 cm. © Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

In Stanyukovich’s admission, we can clearly see a struggle between attraction to, and disavowal of, the distinctive construction of Vrubel’s images, both feelings constantly intertwined. The source of the perturbation is not, of course, in their decorative surface, which without its spiritual, idealistic saturation would most likely be perceived positively. Confirmation of this conjecture can be found in the virtuoso “spotted” colouring of the much acclaimed Mariano Fortuny, to whom Vrubel was compared by Pavel Chistyakov himself. “Not without reason does Chistyakov persist in nicknaming me Fortuna,”[77] wrote Vrubel to his sister about the nature of his “exercises” in watercolour. Stanyukovich, by the way, also noted the influence of the Spanish master on the young Vrubel, who had grown fascinated by Fortuny’s technique largely thanks to lessons in Chistyakov’s workshop. Chistyakov rated Fortuny highly and was personally acquainted with him in Rome. However, Vrubel went much further than Fortuny. The patterns - slippery to the point of appearing chaotic - of his visual world do not limit themselves to a colourful texture of impressions for the viewer’s eye. They reflect the process by which visible nature was formed, by using mosaical pulsations to call artistic images forth from nothingness.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Oriental Fairy Tale. 1886

Watercolour, whitewash, lead pencil, pencil, varnish, collage on paper mounted on cardboard. Sheet: 16.4 × 24.5 cm; cardboard: 27.8 × 27 cm (the image spreads onto the cardboard)

© Kyiv Art Gallery National Museum, Ukraine

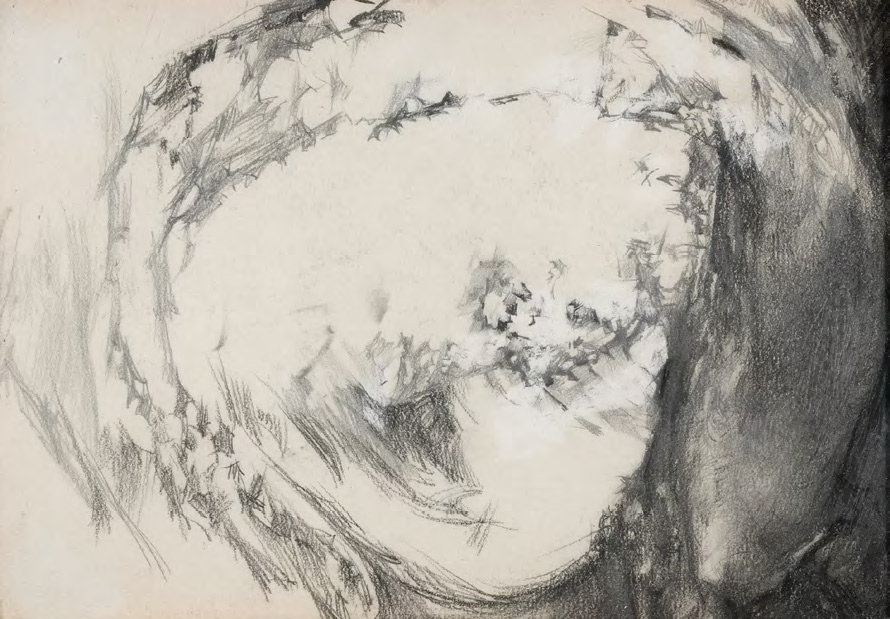

Pattern as a visual and constructive basis for the projection of graphic reality, seen through a spiritual prism, was to form the pillar of Vrubel’s artistic method not only in the early and mature periods of his creative life (in the illustrations to the poem “The Demon”, 1890-91, Tretyakov Gallery, and “Eastern Fairy Tale”, 1886, Kyiv Art Gallery, to name but two), but also in his late period. It is appropriate that Vrubel’s innate understanding of ornament as a structural basis for visual metaphor found expression in the existential coda of his floral universe in the series of “Campanulas etudes” (1904, Russian Museum) of bellflowers, the name of which symbolically reflects the form of the flower (from the Italian campana): a bell calling the soul to a meeting with another world:

If the heart, as it is dying,

Wishes to forget what ails,

The little bell is sure to sing

Melodies of heaven unceasing,

Is sure to tell sweet fairy tales.[78]

Vrubel dreamt about Heaven all his life - its metaphor is embedded in various manifestations of the artist’s creative energy (“Who lives happily? He is happy who has found his path,”[79] as he wrote to his sister). It was not only bellflowers, which in unpredictable graphic “transformations” (from slight to monumental forms) were a sustained motif in his work, represented echoes of Heaven for Vrubel. He saw it also in airy blasts of white iris petals, blue orchids and white, red and pink azaleas (1886-1888, Kyiv Art Gallery). He searched for it in peonies of dizzying sumptuousness (“White Peonies and Other Flowers”, 1893, Kyiv National Gallery) and in chastely tender roses, which, with the natural perfection of a miracle, overshadow the smoky-grey aura of everyday life (“Rose”, 1904, Tretyakov Gallery), a fairy-tale of a Persian carpet (“Girl and Persian Carpet”, 1886, Kyiv Art Gallery), a birch grove in Petrovsky Park (“Portrait of Nadezhda Zabela-Vrubel against a Background of Birches”, 1904, Russian Museum), reverently surrounding the throne of the Mother of God with Child, or alight, like an awakening soul, with the immortal energy of “Resurrection”. It was precisely Heaven that, as we examined at the beginning of the article, was present as the artist stood at the threshold of his creative journey, which, via Byzantium, Old Russian art and the Renaissance, demonstrated the reality of the Godhead that gave his aesthetic understanding of beauty such scale. It was for paradise lost that the soul of Vrubel’s “Demon” (1890) so yearned, like a lily burning in the evening light, filled with elusive reflections of Eternity. It was for an earthly heaven that Vrubel’s Faust and Marguerite searched, crowned in the artist’s fantasy by giant rose-like bellflowers, lilies, camomiles, crimson irises (“Faust and Marguerite in the Garden”, 1896, location unknown; ” Marguerite”, 1896, Tretyakov Gallery) and even thistles (“The Flight of Faust and Mephistopheles”, 1896, Tretyakov Gallery). For him, the violet twilight of the bushy “Lilacs” breathed Heaven, beginning with the lifelike sketches of his Kyiv period (“Lilac Bush”, 1885, Tretyakov Gallery) and ending with the metaphysical reticence of his mature works. Vrubel’s cloud-like nymphs dreamed of it, like the morning and evening flowers that enliven his “Times of the Day”. The very poetic mythology of his flowers, the fantasy of their fairy-tale harmony, dangling in “Old Slavic” gold-tinted pools (“Prince Guidon and the Swan Princess[80], 1890s, Abramtsevo Museum and Reserve), the poppies flaming jimson weed in the steppe of the “red painting”[81] “At Nightfall”, the idyllic hoof-clop of “Pan” on the thick, squally grass - all were born of a yearning to discover within real nature the hidden voices of something otherworldly, possibly the ancient pantheistic Heaven, in which the landscape resembled a deity. Vrubel’s seraphim and prophets (“Seraph”, 1904-05, Tretyakov Gallery; “Six-Winged Seraph”, 1904, Russian Museum; “The Vision of the Prophet Ezekiel”, 1906, Russian Museum) appeared from the spiritual depth of Christian Heaven, in whose luminous glow the curling patterns lift aloft angelic wings. Vrubel was considering the graces of Heaven when he portrayed a small, stricken figure in the right hand of God, a barely noticeable defenceless soul, its silhouette a self-portrait (undated, Manuscript Department of the Tretyakov Gallery, fund 71, inventory 1, item 13). He was was also considering them when, in the sorrowful days of his illness, he sometimes maintained that he was already inhabiting that Promised Land[82].

Mikhail VRUBEL. Six-Winged Seraph. 1904

Oil on canvas. 131 × 155 cm. © Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

The secret logic of the interrelations that act on creativity at the individual level, partly based on love of the aesthetic singularity of the world, can also be seen in the fact that Vrubel’s last work is addressed in terms of its poetics to “The Vision of the Prophet Ezekiel”. If we carefully read the ornament of the lines of the Book of Ezekiel, following the specificity of the way in which the thoughts are expressed, then it is impossible not to be astounded by the glowing naturalness with which the spiritual revelation is woven with decorative elements that, in the nature of things, form part of artistic (sensory) thinking. In the spiritual pattern of Ezekiel’s vision of the Glory of God, we can identify all the essential graphic elements that attracted Vrubel with their metaphoricity into taking his first steps in art (on both the level of meaning and of visual language). In terms of artistic form, the Book of Ezekial possesses a decorative structure that cannot fail to act upon the readers imagination. In the scene of the sacred animals moved by the Spirit, between which moved fire, are descriptions of a sky “the colour of the terrible crystal” (Ezekiel 1:22) and “a throne, as the appearance of a sapphire stone” (Ezekial 1:26), “burnished brass” (Ezekiel 1:7), and “beryl” (Ezekiel 1:16). The light wings of angels (Ezekiel 1:7), “burning coals of fire” (Ezekiel 1:13) had “the appearance of fire”, glowing “as the appearance of the bow that is in the cloud in the day of rain” (Ezekiel 1:27-28). All this flashing space of crystal and lightning surrounding the throne of God, which ever “speaks” of Heaven, found reflection in the spherical multi-dimensional (to the point of chaos) harmony of the dynamic pattern of Vrubel’s unfinished watercolour “The Vision of the Prophet Ezekiel”.

Mikhail VRUBEL. The Vision of the Prophet Ezekiel. Early 1906

Charcoal, watercolour, gouache, coloured pencil on cardboard. 102.3 × 55.1 cm.

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

In the existential context, which the study of art history permits us to see, Vrubel’s late “Campanulas” are not only universally metaphorical, but also subjectively significant, in so far as they allow us to approach the inner structure of the artist’s personality. They are, in some strange way, linked with those “echoes of quiet bells” that “sometimes, with a downcast heart / You can catch with an eager ear”, although “They sail on, sadly fading away.”[83]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Campanulas. 1904.

From the “Campanulas” sketch series. Lead pencil on paper. 12.7 × 18.1 cm

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

There is one page in Vrubel’s creative life which remains understudied to the present day: his poetic jottings. Despite their being so few, they are nonetheless an important source that permits us to understand the creative basis of the artist’s personality and his individual traits as a person. The inner structure of their emotional content may be expressed in a simpler language than the visual idiom in which the artist’s unique poetic freedom is expressed, but they bear witness all the same to the side of Vrubel’s personality that strove to understand life in a harmonic way, stripped of any flamboyant mysticism. Attempts to demonise the artist by linking his illness and his art, which began while he was still living and burst out in an unstoppable avalanche on his death, fail to stand up to scrutiny on both medical and artistic grounds.

Vrubel’s “Demon” is a poetically inspired, dynamic and spiritual force of nature. It is the visual reflection of Vrubel’s musical emotional experience of his time via a romantic theme, the lionised beauty of which could not fail to enrapture a creatively receptive mind. It is telling that, among Vrubel’s poetic manuscripts from the eve of the last, hardship-filled period of the artist’s life (19021904), we find not only lines on Heaven dwellers (“You are born to Heaven / Leave the earthly to the earthly,”84 writes Vrubel in one of his poems), but also quotations from memory of lines from Mikhail Lermontov’s “Demon”.

For a greater understanding of the spiritual gradations within Vrubel’s emotional pattern, from whose germs sprang forth new figurative images, it is important to bear in mind the fact that his innovative visual language was not so much the fruit of protest as an expression on the free professional level of his individual emotional experience of lyrical and elegiac motifs (hence the artist’s love for Russian classics - Turgenev, Pushkin, Lermontov):

In gossamer line

With wings of lace

Brushing young trees

The young flew by,

Singing quiet hosannas:

Does the quiet chime

Of the distant church beyond the woods,

Not shake the air in just that way?[85]

The “peal of bells” heard by Vrubel, but already on a different crest of the new wave in the field of artistic form creation, entered into his final “flowers” - flower atoms - in “Campanulas” on the level of the natural metaphoricity of the artistic image (which, judged from without, might seem unfinished) created from them by the artist, speaking of the beauty of subjective reality even when it is located at the extreme, but maximally whole, indivisible point of disintegration. “You’re a grain of sand / You’re an atom / And no more in this / Abyss of worlds / This universe,”[86] wrote Vrubel, fully aware of the objective character of the time now approaching him. That philosophy of atomicity is also perceptible in the mother-of-pearl abysses of his series of “Shells” etudes (late 1904-early 1905, Russian Museum), unique ornamental worlds containing all the elemental forces of life within their enclosed spaces. Considering spaces that attract us by their sequestered existentialism, the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard wrote of an element in every person that would prefer to live always in the innermost corner of their own shell. That comparison of the soul with a pearl, secreted away in the depths of mother-of pearl folds, received a deep metaphorical development in Vrubel’s poetics: “All that has form has passed through the ontogeny of a shell.”[87]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Pearl. 1904.

Pastel, gouache, charcoal on cardboard. 35 × 43.7 cm.

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The psychologically rich decorative beauty of a pattern, its individual, ornamental rhythm, born in “strivings after the sacred”, received in Vrubel’s “Pearl” not only the power of musical agency, but also a form-creating basis (“Shell”, late 1904-early 1905, the Russian Museum). The artist himself was aware of this, acknowledging that the poetic chaos of the pattern was suggested to him by the contours of the female figure: “For I had no intention of painting ‘sea princesses’ in my ‘Pearl’ [...] I wanted to convey with all reality a drawing from which the play of a mother-of-pearl shell is composed, and it was only after I had made a few drawings in charcoal and pencil and saw those queens, that I started to actually paint.”[88] Vrubel’s visual about-turn revealed itself in the etudes of the shell with no less power than in the flowers of his late period (and in those of his early period, although unconsciously): what was small, previously considered somehow superficial and “decorative” was shown to be something essential and semantic, organically revealing an inner life usually hidden in reality. Vrubel’s contemporaries, who had not seen the artist’s lines about the personality as a grain of sand in the universe, written in words blotted, it would seem, with tears, could not fail to sense this, although they understood the visualised metamorphosis of “big - small” in a different way: some with rejections of “afflicted decadentism”, others with understanding.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Shell. Late 1904 – early 1905.

From the “Shells” sketch series. Charcoal pencil on paper. 36.4 × 41.7 cm © Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

From the “Shells” sketch series. Lead pencil and black watercolour on paper. 17.4 × 25.3 cm.

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

From the “Shells” sketch series. Charcoal, black pastel on paper. 38 × 43 cm © Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

The poet and art critic Osip Dymov, for example, wrote: “Vrubel’s ‘Pearl’ appeared at the exhibition of the Union of Russian Artists last of all. That’s the way it always is: you put on the jewellery when you are already dressed. / Allow me to remind the reader of what a mollusc is. A strange creature, curled up in its shell, which gifts us the pearl. If a grain of sand, a particle of some hard body touches its soft body, invades the intimacy of its life, then a pearl is born. [..] Is not the process by which art is made the same? / [...] At the bottom of art, in its grain, is a phenomenon of real life around which the priceless layers of the artist’s petrified blood form its current eternal sepulchre.”[89]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Shell. Late 1904 – early 1905.

From the “Shells” sketch series. Lead pencil, charcoal, black pastel, whitewash on paper. 17.5 × 25.4 cm.

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Mikhail VRUBEL. Shell. Late 1904 – early 1905.

From the “Shells” sketch series. Italian and lead pencils, watercolour, whitewash on paper. 22.9 × 34.8 cm (without frame).

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Mikhail VRUBEL. Shell. Late 1904 – early 1905

From the “Shells” sketch series. Black pastel, lead pencil, chalk on paper. 17.6 × 25.5 cm

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Mikhail VRUBEL. Shell. Late 1904 – early 1905

From the “Shells” sketch series. Pastel, watercolour, charcoal on paper. 19.7 × 28.3 cm.

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Vrubel’s art always maintained that the poetry of an image is not decoration, but the metamorphosis of the soul. It did so from his very first works, in which the bases of visual language were linked with the principles of assimilation - the transformation, transposition, “prismisation” of obvious and hidden experience in decorative patterns. Vrubel really was, as Alexandre Benois put it, an “orgiast”[90], which is to say that he was an artist who was capable of synthesising poetic thoughts into figurative images. As can be assumed, it was precisely that polysemantic context that Vrubel had in mind when expressing the idea that: “All is decorative, and only decorative.”[91]

The arabesque patterns that came to life in space and were so characteristic of Vrubel were demonstrations of the master’s synthetical approach to an understanding of the inner consistency of the existence of a planar visual world.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Self-Portrait with a Shell. Late 1904 – early 1905

Watercolour, charcoal, gouache, sanguine on paper. 58.2 × 53 cm

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

The artist’s perception of the visible forms of nature as mobile cells of pattern, lacking harshly drawn contours, leads him along the path of transforming a stylised petal into the fragile crease of a bed or into the thickening depths of a pupil, darkening in the untrustworthy light of a changing face (“Self-Portrait”, 1885, Kyiv Art Gallery; “Self-Portrait”, late 1904 - early 1905, Russian Museum). The visual philosophy of both his most dramatic compositions and his most intimate motifs - for example, the sketches depicting a bed after a sleepless night, a subject rarely encountered in world culture (the series of “Insomnia” etudes, 1904, Russian Museum) - is at once ornamental and psychologically dynamic, which is to say directly linked with the emotional experience of the movement of time through the soul, through that “prism of the soul” that is so often referenced in relation to Vrubel, and which was for the artist a genuine source of creatively important observations, observations that were musical in their synthesis of the emotion they contained: “A prism in ornament and architecture is our music.”[92]

Mikhail VRUBEL. Red flowers and Begonia Leaves in a Basket. 1886-1887.

Watercolour, varnish on paper. 38.5 × 32.2 cm

© Kyiv Art Gallery National Museum, Ukraine

![Mikhail VRUBEL. Sketch of a tile. [1890s]](https://www.tg-m.ru/img/mag/2021/3pr/art_72pr_01_203.jpg)

Mikhail VRUBEL. Sketch of a tile. [1890s].

Pencil on paper. 16.8 × 10.1 cm.

© Abramtsevo State Historical, Artistic and Literary Museum-Reserve

Flowers were also linked with the idea of patterns as an essential principle of form creation in Vrubel’s art. Their poetic visual transformations allow us to reach the conclusion that the artist’s ornamental thinking is one of the most important themes for discussion in terms of the uniqueness of his individual language, inextricably linked with his fate in both its creative and personal aspects.

Mikhail VRUBEL. Photograph from the studio of Karl Fischer. 1900s

© Manuscript Department, Russian Museum. Fund 85. Inventory 1. Item 194. Sheet 3