Two Female Faces of the Art of Colour Etching: MARIA YAKUNCHIKOVA AND YELIZAVETA KRUGLIKOVA IN PARIS

In European art, the period 1850-1900 saw a crisis in engraving as a printing technique and the birth of engraving as a new artform with its own distinctive means of expression.

The pace of this revolution was especially dynamic in Paris, one of the most advanced centres of printmaking development, and it was from this global centre of attraction for all artistic souls and communities of the era that the process spread to different countries and art schools. As it happened, in Russia creative printmaking was pioneered by women. In the early 20th century, Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva was discovering the potential of printing on wood, Nadezhda Voitinskaya-Levidova, the potential of lithography and Yelizaveta Kruglikova, the potential of etching.

Yelizaveta KRUGLIKOVA. Self-portrait. Second half of 1890s

Watercolour, whitewash, black and graphite pencil on paper. 16 × 12.5 cm. © Tretyakov Gallery

Yelizaveta Sergeevna Kruglikova (1865 - 1941) started etching in Paris in 1902-1903, and spent her entire life in service to the art of engraving on metal plates, making a priceless contribution to the development of this art's most diverse varieties, but, first and foremost, to the development of colour etching. Few people know, however, that another woman had trodden this path before her - 1894 had seen the short-lived rise to fame of 24-year-old Maria Yakunchikova (1870 - 1902), who displayed at the five colour etchings at the Salon du Champ-de-Mars in Paris: “Quiétude”, “L’Irréparable”, “L'Effroi" (Fear), “Tete de mort" (Skull) and “Le Parfum".

Maria Yakunchikova. 1890s

Photograph. Private collection

The two women were very different. One of them lived within a network of relatives - her mother, sisters, uncle, aunt (the uncle's second wife) and children - in the respectable 8th arrondissement in Paris, on Avenue de Wagram, in a house overlooking the Arc de Triomphe and equipped with a studio that was “a converted dining-room"[1]; later, she became an exemplary wife and mother of two children and died of consumption at 32. The other was an eccentric emancipated woman: in 1895, at the age of 30, she moved to Paris, after having travelled to Greece aboard a cargo ship a year previously. At 35, she turned her studio on Rue Boissonade, in the bohemian Montparnasse neighbourhood, into one of the hubs of Russian life in Paris, a meeting place not only for artists, but also for the likes of Ilya Mech- nikov and Maxim Kovalevsky, Georgi Plekhanov and Vladimir Bekhterev, Alexei Tolstoy, Konstantin Balmont, Valery Bryusov, Andrei Bely, Sergei Diaghilev and many others. At 50, wearing male clothing, in the company of good friends such as Maximilian Voloshin and Tolstoy, she was hanging out in pubs in pre-World War I Paris, dancing with local girls and scandalising the natives[2]. Yakunchikova and Kruglikova probably never met - if they did, no records about it have been discovered so far - but, for all the differences between the lives they lived in Paris, there are certain common features as well, sometimes quite surprising - a result of their shared time period, place and artistic interests.

Like dozens of young ladies from all over Europe and America, both came to the French capital to study painting in one of the local academies and engaged with etching by chance. Both women spent much of their life in Paris, regularly visiting their home country: Yakunchi- kova lived in Paris prior to 1901, when her illness caused her family to move to Switzerland, and Kruglikova, prior to 1914, when the start of World War I found her in Russia and the revolutionary turmoil prevented her from returning, destroying her habitual way of life for good.

Yakunchikova had been attending the Academie Julian since 1889, but quit in 1892, as she became bored with the beaten path and the narrow bounds set by the school, which, to use her words, proposed “to eat when you want to drink"[3]. At that time, she often painted from nature and worked en plein air, as well as producing pottery and making acquaintances among young artists from across the globe. It was at about that time that she began to take an interest in colour etching.

The roots of Yakunchikova's interest in etching are quite mysterious. It is hard to understand why a young girl would go so suddenly for not only etching, but multiplate colour etching, a complex technique that was an absolute novelty at that period. Who taught her, considering that only a handful of people had a command of the technique? Where did she produce her etchings? Practically impossible in a domestic environment, the process pollutes the air and is harmful to the engraver's health, calls for the use of special tools and materials, a printing press and printing ink, and requires skills in handling metal, lacquers, an open fire, varieties of resin and acids. Why did she so suddenly give up the pursuit at which she apparently was good and successful?

Yakunchikova kept diaries and regularly exchanged letters with her favourite mentor Yelena Polenova and sister Natalia (Vasily Polenov's wife) and a lot of detailed information about her life and art is available to us today. These documents, held by Yakunchikova's descendants and relatives in Russia and elsewhere, were used by M.F. Kiselyov, the author of the first monograph about the artist, which was published in the late 1970s[4]. Some of these documents were later published[5]; some were returned to Russia and are held now at various museums. However, Kiselyov's monograph does not explore the subject of etchings in depth and contains errors, including ones originating from the small posthumous article about Natalia Polenova published in the “Mir iskusstva" (The World of Art) magazine in 1904[6].

Maximilian Voloshin's article in the “Vesy” (Scale) magazine in 1905[7] is not illuminating either. Regrettably, Kiselyov's album devoted to Yakunchikova's art, published in a different, post-Soviet period, contains practically nothing new on the subject besides a repetition of the information from the book.[8] The published journals cover the earlier period in the artist's life and stop shortly before the events that interest us. Disappointingly, in the large collection of letters exchanged among Maria and her relatives, which was given to the Tretyakov Gallery's manuscript department, the period 1893-1895 is barely covered. Thus, materials related to Yakunchikova's work on etchings have not been published: they either remain unavailable or have not survived.

Bafflingly, when Yelena came to Paris in May 1895 and had a chance to look at her young friend's artwork, she spoke negatively about Yakunchikova's prints: “I liked very much Masha's piece from last year, ‘Reflets intimes' (‘Intimate Reflections'). It's a very Parisian piece, only the external form is alien while the content grows from the inside and the approach is very compelling, while, to my mind, the execution is serious and painstaking, qualities which her etchings lack so much."[9] In the same year, “The Studio", the English magazine on the problems of contemporary art, ran, in its December issue, Octave Uzanne's article ‘Modern Colour Engraving with Notes on Some Work by Marie Jacounchikoff'[10], arguably, a considerable achievement for a young artist.

This publication answers the main question: Uzanne names Yakunchikova's teacher as Eugène Delâtre (1864-1938), a watercolour artist, print maker and printer and, equally importantly, the son and heir of the acclaimed Parisian pressman Auguste Delâtre, who made an important contribution to the development of European artistic etching. Thanks to this circumstance alone, Delatre Jr. was one of the best etchers of his generation. “His numerous works," notes the author of the article in “The Studio", “entitle him to a foremost place among the innovators in colour-engraving"[11]. Delatre had a significant influence on the development of artistic etching in France; his experiments in colour etching, which began in 1890-1891, laid the groundwork for the modern use of polychromy in engraving and printmaking. Auguste Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mary Cassatt and Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen were introduced to the art of engraving on metal by him, as well as other artists who left a mark in the history of European engraving. After 1907, having inherited his father's business, Delâtre worked with the next generation of avant-garde artists, including Picasso, whose etchings he printed.

The article's author informs readers that Yakunchikova took up etching sometime around 1893 and, in two years, produced “a half-score of plates... which give promise of revealing the most remarkable temperament of the day in this branch of art"12. Doing justice to the technical complexity of Yakunchikova's works, he also strongly appreciates their artistic component. Uzanne writes: “I should hesitate to declare her as yet the superior of her master, Delatre, but she is his equal in the art of triturating the copper plate, and certainly excels him in her vision of things, in idealism, in symbolical spirit, and in far-away reverie"[13].

The article in “The Studio" conveys an idyllic, somewhat romantic picture: a young, very gifted artist and his equally young and talented female student working under his guidance with “enthusiastic labour, quite feminine in its ardour". This picture is not altogether accurate, as, in 1895, Delatre was not 25, as Uzanne indicated, but 31, yet the writer seems to have pinpointed the essence of this relationship. Colour etchings, which were normally produced with the use of four plates, were technically complex pieces. The creation of such an art print requires arithmetically precise calculations; the “programming" skills for the technical part of the process, which should be applied with a clear vision of the end result of a combination of the techniques, paints, and the processes of colour layering; and the knowledge of the succession of these processes. To cope with this type of work, the beginner artist needed to have by her side a reliable and experienced associate. The American Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), who was much older, more experienced and “advanced" in the area of printmaking, remembered that, when a small number of her 10-piece series of aquatints needed to be printed, she had to hire a professional pressman: “The printing [was] a great work. Sometimes, we worked all day (eight hours) both as hard as we could work and only printed eight or ten proofs in the day"14. Additionally, in the case of Yakunchikova, the process also involved the creation of the press plates themselves!

There is a certain, lasting “conspiracy of silence" within the literature devoted to Yakunchikova, which relates to this, the most important period in her life. This calls for an explanation and seems to suggest a hidden drama. It’s an age-old story: a teacher and his female student spending too much time together - and the feeling born out of this collaboration. What was it that destroyed this union? Speculation will lead us nowhere. “The period between 1894 and 1896, a very difficult period in M[aria] V[asilievna]'s personal life, a period of some emotional disruption, moral doubts, the forming of new relationships and strong uncertainty," is how Natalia Polenova characterised this period in her sister's life15. In 1895, seemingly at the same time as Delatre vanished from her life, Yakunchikova gave up etching. In the summer of 1897, she married Leo Weber, her aunt's son from her first marriage, whom Maria had known for a long time, since 1889. He was was her friend and confidant and, as Natalia Polenova put it, “a person who was wholly devoted to her and lovingly understood and appreciated her talent"[16].

Her former mentor, however, appears to have been keeping track of his former young associate's life: the Tretyakov Gallery's Manuscript Department holds a postcard graced with a miniature etching, which Eugene and Auguste Delâtre sent to the Webers congratulating them on the birth of their son[17].

Kruglikova arrived in Paris precisely when the story of Yakunchikova the etcher was drawing to a close.

She started attending the Académie Vitti and, in the evenings, the Académie Colarossi, to polish her drawing skills. Her artistic tastes and ambitions turned out to be more radical than Yakunchikova's. The Academie Julian, where Yakunchikova studied in the second half of the 19th century, was the biggest competitor of the Parisian School of Fine Arts (École des Beaux-Arts), the main centre of art training in France. A course of study at the Académie Julian could open the door for aspiring artists to the School of Fine Arts, where classes were taught by famous artists - some of the teaching staff at the Académie taught at the School and four teachers sat on the jury of the Paris Salon. The Académie Colarossi was an alternative to the official art training curriculum, which, from the young artists' point of view, was too conservative.

The artists with whom Yakunchikova stayed in touch include Eugène Carrière, Paul Besnard and Odilon Redon, whose artwork caught her attention at exhibitions, as well as the American painter Julius Rolshoven, whose workshop she joined after leaving the Académie Julian. Kruglikova's friends and acquaintances included Henri Matisse[18], Polish artist Wfadysfaw Slewinski and Edvard Munch[19]. In the mid 1890s Munch was not yet the iconic painter of the new art, but rather a provincial trouble-maker, an artist who gained a scandalous reputation in his native Norway and in Germany. He spent most of 1896 in Paris, which he come to in order to polish his printmaking skills and where he created lots of etchings, woodcuts and lithographs and built up contacts among the Parisian pressmen[20].

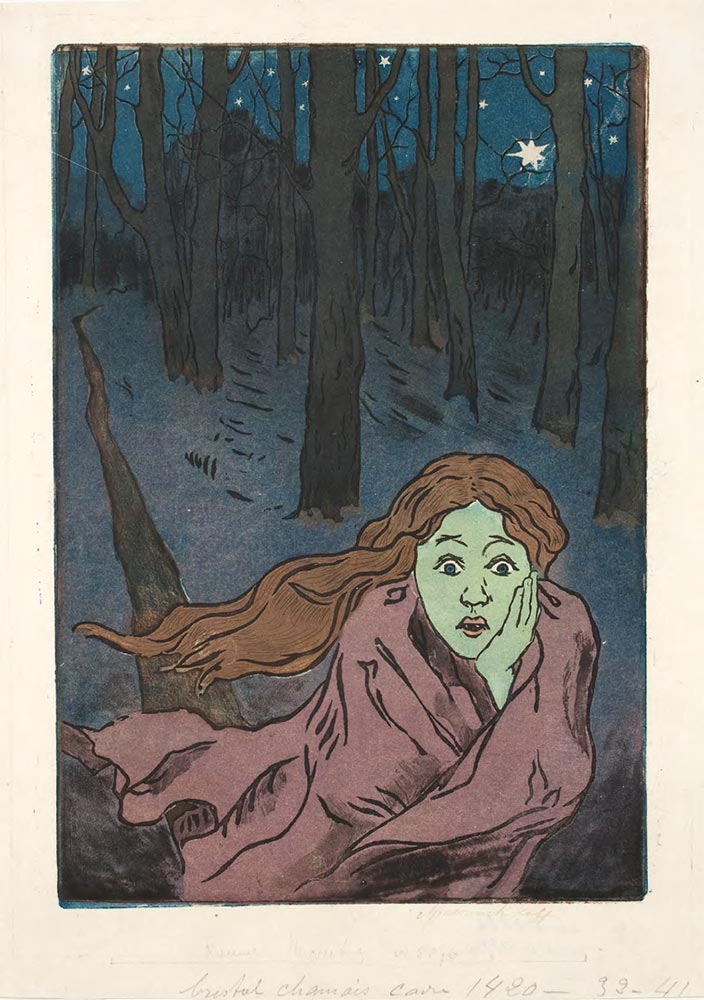

Yakunchikova is known to have taken interest in Munch's art. Mikhail Kiselyov, who has seen the family archive held by the artist's heirs, claims that, in her notebook for 1896, the Norwegian artist's name comes up more than once[21]. The researcher believes, however, that Munch captured Yakunchikova's imagination earlier, when she was working on the etching “L'Effroi". There seem to be obvious parallels between “L'Effroi" and Munch's famed “The Scream" (1893, National Gallery, Oslo). By current standards, however, Yakunchikova cannot be faulted for appropriating or copying the great Norwegian's imagery. Put in its final form by the end of 1893, “The Scream" was first shown at an exhibition that opened on December 3 in Berlin. At approximately the same time Yakunchikova was working on her etching. In February-March 1894, “L'Effroi" had already been submitted to the jury that was selecting pieces for the Salon du Champ-de-Mars, due to open in April. There is no available information about Yakunchikova visiting Germany at that time and perhaps seeing “The Scream". The Munch piece became widely popular only in 1895, when it was reproduced as a lithograph in the French magazine of literature and art “La Revue Blanche". Of course, the artistic value of these two pieces is incomparable: “The Scream" is an iconic image, the epitome of Symbolist art, but Yakunchikova's is a slightly stylised piece, reducing the story's suggestiveness. What seems to be beyond doubt, however, is Yakunchikova's gift of intuiting images and moods born out of the era's worldview.

Maria YAKUNCHIKOVA. L’Effroi (Fear). 1893-1894

Colour etching (aquatint). 29 × 20 cm. © Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Some information about Kruglikova's acquaintance with Munch can be found in a collection of articles and other materials about the former, published in 1969[22], that is at a time when contacts with the “modernists" were regarded as something of a stain on a Soviet artist's professional record. It seems the author of the essay about Kruglikova's art and life relied on some of her memoirs and, aware of the importance of this information, made sure it was published. It also seems very likely that Kruglikova could have met Munch in person. Her close friend Władysław Ślewiński (1856-1918) was arguably one of the leading artists of the “Young Poland" (Młoda Polska) movement, founded by Munch's friend Stanistaw Przybyszewski. At about the same time, in Paris, Ślewiński and Munch each executed a portrait of August Strindberg[23], who regularly socialised with Munch in the Black Piglet tavern in Berlin. Ślewiński was, inter alia, a friend of Paul Gauguin, and Munch was taking a lively interest in his work at that period. The Norwegian artist did not have a chance to personally meet Gauguin, but, as he mixed with people close to him, he could see his woodcuts and engravings on metal plates that Gauguin had left in one of his friends' houses before his last trip to Tahiti[24]. Ślewiński also introduced Kruglikova to Gauguin's artwork. In the same year - 1896 - they travelled to Brittany together and this trip brought about changes in Kruglikova's style - afterwards, her paintings were more in the vein of the Pont-Aven school.

In Paris, Kruglikova experienced a personal drama, the reason for which she and people who knew her were unwilling to talk about later. The artist Yelena Chichagova-Rossinskaya recalls: “When I came there [to Paris-N.M.], Kruglikova was grieving over the breakup with a girlfriend (I would not mention her name), who set her at odds with the artist Ślewiński. This female artist later married him."[25] The girlfriend in question, whom neither Rosinskaya nor Kruglikova herself wanted to name, was Yevgenia Nikolaevna Shevtsova. She belonged to the circle of Russian artists with whom Kruglikova was mixing in Paris and who, like Kruglikova, were former students of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture: Viktor Borisov-Musatov, Alexander Shervashidze, Nikolai Kholyavin, Anna Golubkina, S.Korzinkina, V.Tishin and Alexander Golovin[26].

The two artists' participation in the exhibitions and their choice of the Salons for displaying their works are as illuminating as their choice of academy and of friends and associates. Yakunchikova exhibited in Paris only twice, both times at the Salon du Champ-de-Mars: in 1893, in the section of drawings, watercolours and pastels, and in 1894, displaying her paintings, pastels and etchings. In the second half of the 1890s Kruglikova, displayed her paintings at the Société des Artistes Indépendants (Society of Independent Artists) and the Salon d'Automne (Autumn Salon). According to a critic, this choice reflects their stylistic focus: in the first case, in the vein of impressionism and post-impressionism and, in the second, moderate innovation[27]. As for Yakunchikova, one must admit that she was perhaps following in her mentor's footsteps - since 1892, he had regularly displayed his colour aquatints at the Salon du Champ- de-Mars. Thanks to Eugene Delatre, however, Yakunchikova mixed with the small community of true innovators who were creating the idiom of modern etching, such as £douard Manet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, the inventor of new technologies Felix Bracquemond, kindred artistic spirits from America such as John Whistler and Mary Cassatt, the Dutch artist Johan Barthold Jongkind and others.

The discovery by Europeans of Japanese chromoxylography produced a strong impact on the development of the new idiom in the art of engraving: the decorativeness and sparseness of composition, expressiveness of silhouettes, polychromy, the lucidity of a watercolour and the lightness of paints of the Japanese prints - all this inspired not only admiration and a collector's thrill, but also the desire to master these skills and apply them in work. The exposure to the Japanese prints revived the artists' interest in multi-plate colour printing, the technique that had been invented by Jacob Christoph Le Blon in the early 18th century, but which, a century later, was thoroughly forgotten, and artists began experimenting with the use of watercolour pigments. In the late 1880s, Henri Rivière and Auguste-Louis Lepère pioneered the use of the new technique in the production of xylographs. At approximately the same time, Félix Bracquemond and several other artists started experimenting with colour in etchings. These experiments included, inter alia, attempts to create prints with watercolour effects, using only the aquatint techniques for contouring. To this end, Bracquemond invented a technique called reservage, which produced images that seemed to be drawn with a pen or a fine brush. Many artists eschewed these complex techniques; the already mentioned Mary Cassatt created her masterpiece - a series of ten colour engravings in the Japanese style - combining aquatint and drypoint. Most of Yakunchikova's etchings, however, are pure aquatints and when she employed hatching and a graver in “L'Effroi", they were used solely for the accessory task of retouching.

Yakunchikova's colour prints can be divided into two groups: allegorical and symbolical compositions, including the ones she displayed at the 1894 exhibition, and images of nature to which she added only a delicate touch of Symbolist melancholy and which featured her favourite Russian motifs (“Little Courtyard", “Cemetery", “Le Soir" (Evening)). These pieces were created later, in 1894-1895, and, working on them, Yakunchikova chose techniques more freely: for instance, a graver was abundantly used in the creation of “Cemetery".

Kruglikova took up engraving at a time when colour etching was no longer a novelty, a wide variety of its technical modifications already in use. She became interested in etching thanks to her acquaintance with Victor Joseph Roux-Champion (1871-195), whom she first met travelling across Brittany. A painter and watercolour artist who depicted landscapes, flowers and fruits, Roux-Champion (“Champion" was a made-up addition to the real family name) studied etching under Auguste and Eugene Delatre, used vernis mou (French for soft varnish) and was a co-founder of the Society of Engravers, whose members used this technique. Kruglikova created her first print in 1902 under his guidance. As she reminisced later, it was the only lesson he gave her - after that she was working independently[28].

In 1903, under the tutorship of the aquatint printmaker Manuel Robbe (1872-1936), she mastered these techniques and used his workshop to print her first colour prints. After that, Kruglikova developed a serious interest in etching, bought a printing press and set about producing colour prints, mostly using such techniques as aquatint and vernis mou.

Kruglikova was skilled in a wide variety of engraving and printing techniques, but her painter's temperament and spirit of experimentation steered her towards simpler printing techniques. Instead of multi-plate options, she preferred single-plate colour printing and, logically enough, later took up the long-forgotten monotype technique. Kruglikova recalled: “As I have always printed my etchings myself, I became a skilled printmaker. As I made colour prints not only from aquatints (always single-plate) but also from vernis mou pieces, where only contours were etched and, so, you had to spread a variety of paints over smooth areas, it occurred to me that working on drafts and sketches I could do without etched lines."[29] Kruglikova exhibited her etchings and monotypes in 1907 at the Galerie des Arts Décoratifs and, in 1908, at her solo show in one of the numerous exhibition spaces on Rue Laffitte. In 1904, she joined the Society of Original Colour Prints. She wrote a concise but very articulate summary of what she knew about the history and various techniques of printmaking, and the article was first published in the “Iskusstvo v Yuzhnoi Rossii" (Art in Southern Russia) magazine in 1914[30]. Another lifelong line of work was teaching etching. In 1909-1910, in her studio on Rue Boissonade, she trained students from the Academie de La Palette. Practically every Russian artist who came to France to study engraving or simply took an interest in etching became her student: Maximilian Voloshin, Matvei Dobrov, Konstantin Kostenko, Ivan Yefimov, Nina Simonovich-Yefimova, Lyubov Shaporina, Veniamin Belkin, Nikolai Tarkhov, and so on. And in Russia after the revolution, in 1922-1929, she held a professorship and taught engraving at the printing department at the Leningrad Académie of Fine Arts, enjoying universal popularity and respect as the key artist of the Leningrad school of etching. Arguably, Moscow artists were also exposed to Kruglikova's ideas and methods thanks to Matvei Dobrov, who in 1908-1909 was Kruglikova's student in Paris, then went on to become one of the directors of Ignati Nivinsky's etching workshop and taught for many years at the Surikov Art Institute.

As for Yakunchikova, in the 20th century, her name and diverse legacy, which consists of paintings and drawings, as well as book design, the most interesting pokerwork pieces, textile designs and ceramics, were forgotten both in her home country and in the hustle and bustle of the international art scene in Paris. In the European art scene, only her etchings have been duly appreciated, but they are a part part of her legacy that is practically unknown in Russia, no matter how small this part is and no matter how brief was the period of her life when she was engaging with this artform. In authoritative European reference books, Yakunchikova is referenced first of all as a prominent etcher[31].

- Yakunchikova, M.V. Letter to Natalia Polenova. January 15, 1892. Manuscript Department, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 54. Inventory 3. Item 12223. Sheet 3 reverse.

- Tolstoy, A.N. ‘14th of June’ // “Paris Before the War in Monotypes of Yelizaveta Kruglikova”. Petrograd, Union publisher [1916].

- Yakunchikova, M.V. Letter to Yelena Polenova. January 1-6, 1892. Manuscript Department, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 54. Item 9690. Sheet 2 reverse.

- Kiselyov, M.F. “Maria Vasilievna Yakunchikova. 18701902”. Moscow. 1979.

- Kiselyov, M.F.; Yakovlev, D.Ye. ‘The Diary of Maria Yakunchikova: 1890-1892 ‘. “Cultural Heritage. New Findings”. Annual publication. 1996. Likhachyov, D.S., ed. Moscow. 1998. (Literature, art, archaeology.) Pp. 469-497.

- Borok, N. (Polenova, N.V.) ‘M[aria] Yakunchikova’ // “The World of Art”. 1904 (3). P. 120. (Hereinafter referred to as Borok).

- Voloshin, M.A. ‘Art of Maria Yakunchikova’. “Vesy”. 1905 (1). Pp. 30-38.

- Kiselyov, M.F. “Maria Yakunchikova”. Moscow. 2005.

- Sakharova, Ye.V. “Vasily Polenov. Yelena Polenova. A Chronicle of the Artists’ Family”. Moscow. 1964. P. 533.

- Uzanne O. ‘Modern Colour Engraving with Notes on Some Work by Marie Jacounchikoff’ // “The Studio”. Vol. 6. 1896. Pp. 148-152.

- Ibid., p. 152.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ives C.F. “The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints”. New York. Pp. 45-46.

- Borok, p. 120.

- Ibid.

- Manuscript Department, Tretyakov Gallery. Fund 205. Item 361.

- “Yelizaveta Sergeevna Kruglikova: Her Life and Art”. Collection of articles and other materials. Leningrad. 1969. P. 69. (Hereinafter referred to as “Kruglikova: Her Life and Art”.)

- Ibid., p. 15.

- N^ss, A. “Edvard Munch. A Biography of the Artist”. Moscow. 2007. P. 145. (Hereinafter referred to as N^ss.)

- Kiselyov, M.F. ‘Maria Yakunchikova and Russian Art Deco’. “Our Legacy”. 2000(54). P.

- “Kruglikova: Her Life and Art”. P. 15.

- В. Wladyslaw Slewinski. Portrait of August Strindberg. C. 1895. Pastel on carton. 60 х 45 cm. National Museum, Warsaw; Edvard Munch. Portrait of August Strindberg. 1896. Lithograph. 60 * 46.3 cm

- N^ss, p 145.

- Kossowska, I ausfuhrliche Biografie bei Culture.pl, Kunstinstitut der Polnischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, April 2003 (https://culture.pl/pl/tworca/wladyslaw-slewinski); “Kruglikova: Her Life and Art”, p. 71.

- Ibid., p. 59.

- Tolstoy, A. ‘Artists of Russian Paris’. “Our Legacy”. 2012(104).

- Kruglikova: Her Life and Art”, p. 16.

- Ibid., pp. 43-44.

- Kruglikova, Ye.S. ‘Artistic Prints and the Techniques of Etching and Monotype’. First published in the magazine “Art in Southern Russia”. 1914(3-4). Pp. 103-114.

- Benezit E. “Dictionnaire des Peintres, Sculpteurs, Dessinateurs, et Graveurs”. Paris. Vol.5. 1976. P. 695.

Colour etching (aquatint). 19.7 × 15 cm. Colour print variant

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Colour etching (aquatint). 19.7 × 15 cm. Colour print variant

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Colour etching (aquatint). 19.7 × 15 cm. Colour print variant

© Tretyakov Gallery

Colour etching (aquatint). 12.7 × 16.8 cm. Colour print variant

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

© Manuscript Department of the Tretyakov Gallery

© Manuscript Department of the Tretyakov Gallery

Colour etching (aquatint). 29 × 23.2 cm

Private collection, Paris

Lithograph. 45.7 × 32 cm

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts

Oil, tempera, pastel on cardboard. 91 х 73.5 cm

© National Gallery, Oslo

Colour etching (aquatint). 24.5 × 28.7 cm. Imprint from the base plate. Etching (reservage, aquatint)

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Colour etching (aquatint). 24.5 × 28.7 cm. Colour print variant

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Colour etching (aquatint). 24.5 × 28.7 cm. Colour print variant

© Tretyakov Gallery

Colour etching (aquatint, soft varnish). 26.1 × 42.8 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Colour etching (aquatint). First stage. 23.8 × 32 cm. Second stage. 18.3 × 32 cm. Colour print variant

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Colour etching (aquatint). First stage. 23.8 × 32 cm. Second stage. 18.3 × 32 cm. Colour print variant

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Colour etching (aquatint). 19 × 34.5 cm. Imprint from the base plate. Etching (graver, reservage)

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Colour etching (aquatint). 19 × 34.5 cm. Second stage. Colour print variant

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Colour etching (aquatint). 19 × 34.5 cm. Third stage. Colour print variant

© Tretyakov Gallery

Colour etching (soft varnish, monotype). 40.7 × 30.8 cm. Printing variants

© Tretyakov Gallery

Colour etching (aquatint). 21.7 × 52.7 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Colour etching (soft varnish). 36 × 25.8 cm

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts

Black paper mounted on thin cream-coloured cardboard. 13.2 × 20.7 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Black paper mounted on thin grey cardboard. 17.7 × 24.1 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery