"No matter that we seldom come together - our connection is deep". YELENA POLENOVA[1] AND MARIA YAKUNCHIKOVA

“Are we capable of leaving a unique mark on European art, or can we hope only to keep up?” [...] In order to win this dazzling European competition, we need both serious preparation and true audacity.”[2] As Sergei Diaghilev contemplated the possibilities, he remained convinced that actively engaging with Western art was imperative, both to steer clear of shallow imitations and to find similar pursuits of national identities in other cultures.

If we accept Diaghilev’s reasoning, we have to acknowledge that the work of these two Russian artists, Yelena Polenova and Maria Yakunchikova, did leave a “unique mark" on European art - Polenova's “serious preparation" and Yakunchikova's “true audacity" paved the way for Russian Art Nouveau. In the words of the celebrated contemporary dancer and choreographer Serge Lifar, the artistic community inspired by Mir Iskusstva (“World of Art") magazine idolized Polenova, and Diaghilev himself venerated Yakunchikova's work.

Valentin SEROV. Portrait of the Artist Maria Vasilievna Yakunchikova. 1887

Oil on canvas. 35.8 × 24 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

It was not only Yelena Polenova's own multifaceted oeuvre that was such an important influence on Russian art. Polenova (1850-1898) recognized and valued her exceptional ability to inspire others, build their confidence, give them direction and raise their spirits. The person closest to Polenova, both as a friend and as an artist, was Maria Yakunchikova (1870-1902), and their friendship and professional collaboration exemplified both profound “artistic convergence" and deep respect for each other's distinctive styles. The fact that Pole- nova was twenty years older was not an impediment - indeed, it proved to be beneficial to both of them, since for the first time Polenova was able to generously share everything that was at the core of her artistic life, and was met with sincere interest and appreciation. Everything that was of interest to Polenova was also exciting to her younger fellow artist, and this also helped Yakunchikova come into her own much sooner.

Yelena Polenova. 1889. Photograph

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Polenova and Yakunchikova first met - briefly - when in 1882 Polenova's brother Vasily married Maria Yakunchikova's older sister Natalya. In September 1882 Polenova and her mother moved to Moscow, and the large extended Polenov family took residence in a rented mansion on Bozhedomka Street. At the time Yakunchikova was only 12, and naturally the 32-year-old Polenova took little interest in her. In 1885 Yakunchikova, having fallen in love with art, began taking classes at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture; it did not take long for her to develop a close bond with her older sister's artistic family.

In 1885 Polenova took charge of the furniture-making and carving workshop at the Abramtsevo artists' colony. She was dedicated to the cause of preserving traditional Russian folk art through in all its forms: applied arts, wooden architecture, and folk fairy tales. To this end, Polenova was not interested in working form the images in luxuriously-bound albums, but shared the enthusiasm of the entire Abramtsevo community (and especially Yakunchikova) for collecting household objects from nearby villages, as well as during expeditions to other Russian regions. Polenova executed more than a hundred sketches of carved wooden objects. Later on, in 1899, Yakunchikova would make her own contribution to this field of decorative art by creating two wonderful pieces, a wooden shelf for her son and a decorative panel she called “Little Town".

Yelena POLENOVA. Artists at the painting gathering at Vasily Polenov’s house. 1889

Watercolour on paper. 11.6 × 19 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Polenov painting gatherings. Andrei Mamontov at the front (from his back), the artist's wife Natalia Polenova on the left.

Polenova's love and deep knowledge of Russian architecture fell on fertile ground in Yakunchikova's work by adding a poetic and pensive atmosphere to her architectural landscapes.

Yakunchikova witnessed Polenova's creative process when the latter worked on her fairytale-themed masterpieces in Abramtsevo and Kostroma. Polenova created illustrations for Russian fairy tales by drawing from traditional Russian decorative patterns, folklore, and literally “everything that feeds the imagination of the Russian people." In this context, Yakunchikova's “Little Town" is reminiscent of Polenova's “mushroom cityscapes" illustrations for her “War of the Mushrooms".

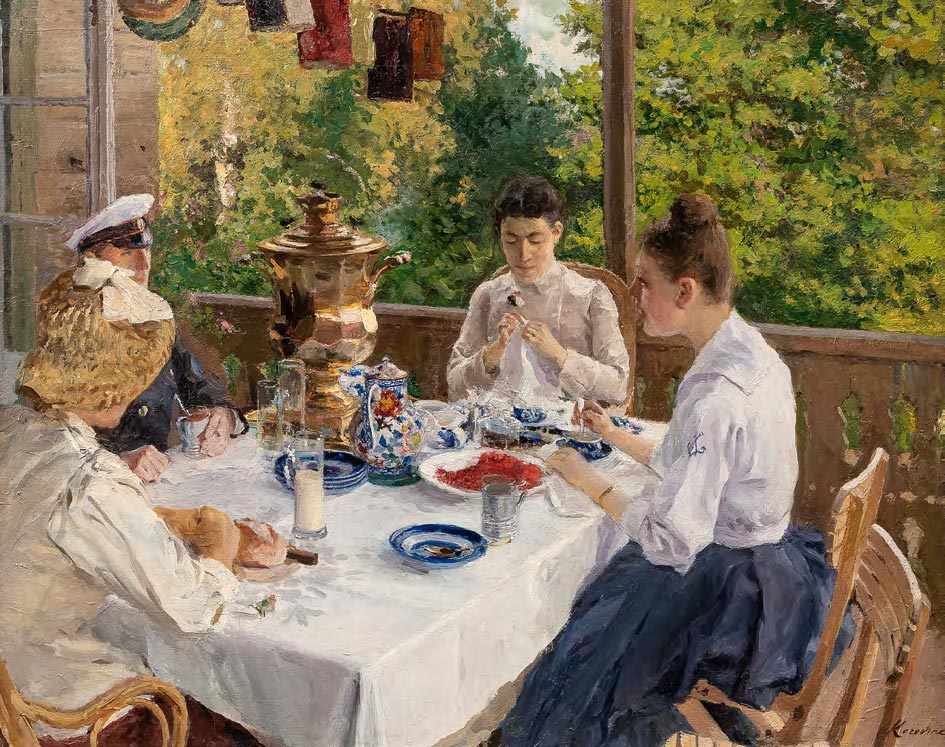

Konstantin KOROVIN. At the Tea Table. Sketch. 1888

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard. 48.5 × 60.5 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Polenova's illustrations to the fairy tales of her “Kostroma period", such as “Son Philip" may have inspired Yakunchikova to create her wonderful illustrated alphabet. These works by both artists are connected by their brilliant stylization of forms. Polenova was the first Russian artist whose oeuvre included a significant number of colour illustrations to fairy tales, while Yakunchikova became the first one to focus on the coloured etching technique. Both artists, however, were equally fascinated with decorativeness, traditional ornamental patterns, and the poeticization of Russian antiquity.

In spring 1889, after being diagnosed with tuberculosis, Yakunchikova went abroad for treatment and settled on Biarritz. From that point on, the two artists stayed in touch through correspondence. When Yakunchikova's health improved, she moved to Paris and began attending the Academie Julian, a private painting school. Polenova also came to Paris and visited the academy. She did not like the school, but brought home a promotional booklet nonetheless.

Yakunchikova worked at the studio of William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury. She gave a rather in-depth account of her work in a letter to Polenova: “Here is one thing: the sitters are beautiful, the best. Yesterday there was this woman there, who stood with her back to us, her arms pressing on the wall, and her head resting on them. With all these hues blending, I thought [painting] it was an incredibly difficult task, but it would be so good to capture it exactly, with that grey buckram background, not just quelle que chose de vague.”[3] Apart from seeing Yakunchikova, it was Polenova's desire to visit the French capital and its countless exhibitions that brought her to Paris. Throwing herself into its bustling artistic scene and connecting with the audacious, ground-breaking French art gave Polenova the feeling of creative “self-renewal”. Indeed, it was after she visited the 1889 Exposition Universelle that Polenova's work began to reflect her commitment to new expressive means and new themes, and she began to move away from Realist art to Symbolism, and to painting the irrational . In 1885 Polenova made her first attempt to paint the complex and mysterious world of Konstantin Fofanov's poem Clear Stars (1885):

Clear stars, splendid stars,

Whispered fairy tales to flowers...

“That means I have to paint the night, the stars, the night air and colours - in a word, all the wonderful poetry of a summer night,”[4] Polenova wrote in a contemporaneous letter. However, she did not end up completing a painting - it was Yakunchikova who created a print with a similar mood.

Many paintings that were exhibited at the 1889 Exposition Universelle made a great impression on Polenova, and reinforced her interest in Symbolism. Having returned to Moscow, Polenova wrote to Yakunchikova asking to to learn which works had attracted her friend's attention. She may have been looking to confirm their common artistic vision, but was also hoping that Yakunchikova would describe those paintings in her letters - Polenova valued her friend's remarkable way with words, her ability to describe images and colours. Quite often Polenova found inspiration in Yakunchikova's letters, as was the case with the simple and lyrical painting called “Vagabond”. Yakunchikova's description of the painting's symbolic images left a deep impression on Polenova: “... I will paint my own vagabond. A homeless wanderer, a miserable outcast, he is dragging himself along a muddy road on a late autumn day. It has to be clear that he is exhausted and defeated, so weary of everything, so indifferent to his surroundings that nothing makes him happy, and nothing can or ever will - he is too tired, too tired of living.”[5]

Yakunchikova's descriptions were characteristically impressionistic: she focused on those details that affected her the most, calling them “fragments”, such as bare willow branches against the sun, a red pillow, or a white flower. For Polenova, this was more than enough - just look at the similarities between Yakunchikova's “Red Parasol” and Polenova's watercolour “The Sails”.

Maria YAKUNCHIKOVA. Red Parasol. 1890s

Watercolour on paper. 9.5 × 8.9 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

This is perhaps the reason why Yakunchikova's oeuvre includes so many unfinished sketches that do not, however, feel like unfinished works. Those very “fragments” that were to become the focus of her painting are executed exquisitely, in minute detail. In some of her paintings, such as “Summer Landscape. The Gate" and “By the Window", Polenova also left small areas of bare canvas, the texture and colour of which served as an important means of creating “immediacy of impression" and the feeling of space and open air.

Here is Yakunchikova's delightful depiction of the Tuileries Garden in Paris, which reads almost as a poem describing her painting: “This is a wonderful season here: there is no sun, the trees have dropped their leaves, and all that is left is bare branches and damp fog. The Tuileries, which is so dry in the spring, so dusty and unbearable, has turned into something almost touching. Large black linden trunks and plane tree trunks meeting the dark wet grassless earth beneath them, cold stone benches which nobody wants to sit on, wonderful vibrant dahlias, the wide and deserted middle walkway. Basically, few visitors, dampness, fog - charming."[6]

Living in Paris gave Yakunchikova more opportunities to keep abreast of the latest achievements and movements in visual arts. Despite Polenova's all-encompassing influence on her artistic evolution, it is obvious that Yakunchikova developed a painterly manner that is much more spontaneous and unrestricted, both in terms of style and choice of subjects. Polenova and Yakunchikova are both very “Russian" artists - the quiet work of the human soul, the desire to move people to think about the world and our existence in it was always at the core of their work. Both artists took a long time working on each of their paintings, waiting for that moment to arrive when they could paint “with joy and without pressure". Their experiences suggested that the work of an artist is unpredictable and hard, and one has to wait for inspiration. Both Polenova and Yakunchikova looked forward to that moment of exhilaration, when the artist's heart is full, she needs to paint, and she can paint. They called inspiration “communing with the vision" and considered it “a mutual friend". Yakunchikova, in a letter on New Year Eve, shared a wish with her friend, something she thought was equally important to both of them: “may the vision never leave you, and may those close to you be understanding of it."

Maria YAKUNCHIKOVA. Tree Lined Avenue. 1898

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard. 27.8 × 21.6 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Yakunchikova often wrote to Polenova about new developments in the European art world, and sometimes mailed catalogues of Symbolist artists' exhibitions with her letters. She believed that the goal of the Symbolist movement was to “add a mystical element to art". Indeed, it was in their letters that they first mentioned the “spiritual and cultural Order of the Rose Cross". Polenova was very interested: “About this Rose + croix, and Symbolists in general, please write more [...]. If it is not too much, please make two or three sketches for me - I am very curious about this."[7] The artist's pleas became even more persistent after Yakunchikova visited England in 1895 and The Studio magazine published an essay about Yakunchikova's etchings. “Please write to me about your London experiences - I am quite interested in what the English are doing. After all, they are great stylists, and it is in part to them that present-day art owes its pivot from the ultra-realistic to the abstract and spiritual,"[8] Polenova asked in a letter to her friend.

While Yakunchikova was still quite uncertain about this artistic movement (she called it “Symbolist buffoonery", and the artists “empty-headed charlatans"), she was drawn to the work of two particular artists: Eugene Carriere, famous for his somewhat affected monochrome palette and exquisite serpentine lines, and Paul-Albert Besnard, a master of light and shadow. In 1892 she met both of them and wrote an enthusiastic account to Polenova: “This is true art: to create an image in one's mind that springs from the sum of past experiences."[9]

In response, Polenova came up with the most authentic and clear-cut definition of art and artistic inspiration she had articulated to that day: “Here is how I see it: if an artist struggles to come up with a subject, or can barely find something to paint in real life, merely for the purpose of painting it, while also remaining quite indifferent to his work, this is not art, and he is not a true artist.

“However, it does not matter how inspiration strikes him, whether the entire painting is revealed to

him clearly and definitively, in the shape of a vision, or it starts as a vague feeling, maybe even a mood or a wish, to be later shaped and expressed through some aspects of reality."[10]

In her own work, Polenova continued to try to realize her “visions", but most of the time did not get beyond studies, such as “Apparition" (1890s) and “The Youth Bartholomew. Serguis of Radonezh and the Hermit" (1890s). Polenova finished just two paintings, “Prince Boris before Assassination" and “Apparition of Princes Boris and Gleb".

Yakunchikova and Polenova discovered Japanese art in Paris in 1889. In her personal notes Polenova mentions Le Japon artistique - a magazine dedicated to Japanese art, it was published in France by Siegfried Bing, a passionate collector who also organized exhibitions of Japanese paintings. Most importantly, Polenova copied two traditional Japanese poems from the magazine, so impressed was she with their depth and symbolism:

“Spring came when the earth was still covered with snow

Frozen tears in nightingale’s eyes

Will they melt, too?

A poem by a Japanese empress, 9th century."

“I walked through fields and plucked wakana[11] sprouts Down falls the snow and adorns my sleeves with stars. A poem by the young Emperor Koko, 9th century."

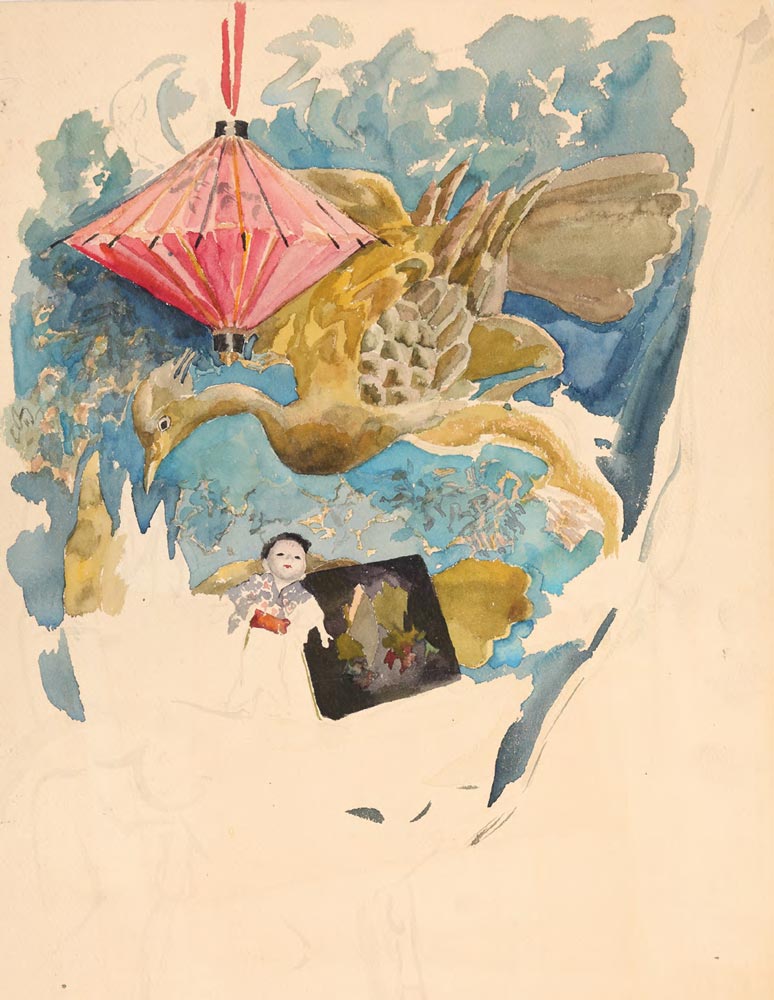

Why did these verses touch them so? Naturally, it was not just the poems' vivid images, but also the deep meaning that lies beneath depictions of nature and plants in Japanese art. The Japanese doll, parasol and fan in Yakunchikova's “Room in Avenue de Wagram", “Interior", and “Chinese Lantern" are simply exquisite objects. However, when Polenova and Yakunchikova painted studies of flowers, their sophistication, flawless motifs, clean lines and refined minimalism clearly evoke Japanese art, albeit without its multidimensional meaning.

Maria YAKUNCHIKOVA. Chinese Lantern. Late 1880s

Watercolour on paper. 38.0 × 27.8 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Both artists were interested in the purely painterly challenge of showing emotionally charged states in nature: melting snow, the sound of wind in the trees, moisture in the air... This inevitably led them to Symbolism. “I have so many ideas, so many plans that I am afraid nothing will come of them. This spring is so cold - it is either wet snow or rain all the time - that it feels almost as good as autumn, and inspires me in the same way. What do I do these days? Not too much, but I feel a great deal, and such are, of course, the best moments of our lives, aren't they? My mind is always full of new ideas and new paintings, and I am sure that I can bring them to life. For now, this is more than enough, and all I want is for this wonderful state of mind to endure,"[12] Polenova wrote to Yakunchikova.

The 1890s were a consequential time for both artists. Polenova developed a passion for Symbolism in literature and painting - she even copied sections on Stephane Mallarme, Maurice Maeterlinck and Paul Verlaine from Max Nordau's book “Degeneration" In Moscow she also attended Modest Durnov's[13] lectures on new artistic movements, and expressed her regret that very few gravitated towards or understood the kind of art about which he was so passionate. Again and again Polenova took pleasure in reading Dante Gabrielle Rossetti's biography, and acknowledged she admired him more than his student and follower Edward Burn-Jones,[14] whose paintings she saw at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. After a talk about the Pre-Raphaelites, which had a profound effect on her, she “came home in a daze."[15] It is also likely that Durnov and Polenova, who knew each other, became closer through their shared love for the poetry of Konstantin Balmont.

Symbolist poets believed that for the purposes of poetry and art it was not physical objects that mattered, but rather their properties, such as colour and sound. In Balmont's opinion, a poet had to see, hear and feel the sound. Polenova filled her notebooks with statements that resonated with her own “slightest stirrings of the soul and emotional undercurrents": “We will spot colour in sound and sound in colour. Poetry, due to its symbolism, should be like music, which introduces a subtle mood into the listener's soul without evoking any images. [...] To name something is to destroy three quarters of the joy that guessing brings; we must lead up to it, intimate it."[16] Balmont believed that the American poet Edgar Allan Poe, a deeply intellectual man who lived in memories of the past and was endowed with a feeling for “alien worlds", was the first major Symbolist of the 19th century. It was as far back as 1893 that Poe's poem “The Raven" inspired Polenova to paint her “Late Autumn's Sobbing (Tempest)": “I was working on a study (maybe the tenth one) for a theme that could best be expressed in the words ‘late autumn's sobbing'; I would like to express the anguish of loneliness."[17] (Here 'late autumn's sobbing' is a quotation, translated back into English, from Konstantin Balmont's celebrated but rather free Russian translation of “The Raven" by Edgar Allan Poe; the words correspond to the original's 'bleak December'.) In a letter Polenova quoted Balmont's translation of the following lines from “The Raven": “Ah, distinctly I remember, it was in the bleak December,/And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor." Polenova showed her “Tempest" at the Exhibition of New Art, which Ilya Repin organized in 1896 in St. Petersburg. She also did all she could to make sure that Yakunchikova showed her work at this exhibition, namely new decorative wood panels executed in a technique Yakunchikova had invented: pyrography followed by painting with oils. This technique brought oil painting even closer to decorative and applied arts, in line with the Art Nouveau movement.

In 1891 Pavel Tretyakov acquired Yakunchikova's pastel “Bell Tower of the Savvino-Storozhevsky Monastery near Zvenigorod". Yakunchikova was encouraged, and in 1892 ventured to submit one of her works to the Champ de Mars Salon in Paris, only to be rejected. Polenova thought that this setback was due to the fact that the style of the piece was very “French" and did not stand out among other works, while in Russia it would have certainly gained attention. “Live abroad. Enjoy it, draw inspiration from it, but send your paintings here - it will be marvelous!"[18] Polenova's support had its effect: “if you want to take the next step forward now, it is more important to paint something enduring and substantial, and definitely show it, rather than just work in your studio or study painting technique. Whether this work gets accepted or not is not even that important (even though it is always nice to be accepted), but it is essential to finish something and show it to people who you do not know."[19] And this happened - the 1893-1894 Salon catalogues listed Yakunchikova's works. In 1894 she showed five etchings to great acclaim: “Peace", “Fragrance", “Irreparable", “Fear", and “Skull". At this point, Yakunchikova was working on mastering everything that Western European Symbolism and Art Nouveau have to offer.

Maria YAKUNCHIKOVA. Oar with Water Lilies

Oil on board, pyrography. 45.4 × 70.0 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Yakunchikova appreciated her friend's support (“definitely exhibit it!"), and in 1894 went back to the subject of that first rejected painting, “Reflection of a Personal World", in a conscious attempt to bring symbolic underpinnings into the composition.

Both artists strove to express poetic sentiments and ideas in their paintings. However, Polenova, who was a deep and deliberate thinker, claimed that Yakunchikova's gift was unique, and her creative ideas were unlike those of others. She even came up with a definition of Yakunchikova's talent: “unique, never happy, and always questioning,"[20] which might just as well be applied to her own.

Yakunchikova spent every summer in Russia. She painted landscapes in various rural locations, such as Morevo, Vvedenskoye (the estate that her family had sold), and Bekhovo, the latter while staying with the Polenovs at their Borok estate. The muted and poetic landscape along the Oka River and the delicate refinement, comfort and family atmosphere of the Polenov estate all came together in Yakunchikova's marvelous painting “By the Fireplace at Borok" (1895). This work was a great testament to Yakunchikova's mature talent and her masterful grasp of one of the hardest painterly techniques - rendering light and shade, daylight and twilight. Qualities that she admired in Anders Zorn's paintings were now present in her own works: “shade and light, everything blends together and comes alive."[21]

As artists, Polenova and Yakunchikova shared their most important goal: to create music through painting, where the colour scheme would reflect the artist's emotional state. Both women loved music and heard it “in colour". Indeed, music inspired Polenova to create especially beautiful ornamental patterns: “having listened to good music, she clearly saw ornaments in her mind... [...] Polenova's ornamental patterns are filled with a special fragrance - their colours are delightful, and the designs are quite fantastical. [...] colour schemes and shapes are so delicate that one can only admire them. [...] These are not simply pretty patterns - they most certainly carry mysterious thoughts, and their colours conjure sounds."[22]

Yakunchikova created equally sophisticated and thoughtful ornamental patterns, but the fact that she was much more immersed in - “her eye was used to" -contemporary European art helped her create designs that were perfectly aligned with the Art Nouveau aesthetic, such as her ex libris with self-portrait.

Yelena POLENOVA. Dandelions. Embroidery pattern. 1897

Sketch for a dining room design at Maria Yakunchikova’s house in Naro-Fominsk near Moscow. Joint project with Alexander Golovin Pencil, whitewash, watercolour on paper. 33.9 × 46 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Refined, sensitive and spiritual, burdened with premonitions stemming from poor health, Polenova and Yakunchikova shared an acutely tragic view of life. Hence Yakunchikova's attraction to the subject and attributes of death: images of cemeteries, crosses, and skulls are common to her oeuvre, but there is no fear, just serenity and sadness. As for Polenova, her works are filled with ominous and disturbing moonlight, and a sense of stealthy danger (“Beast", 1895-1898) and suffering (“Fear", 1890s).

Over time, mysticism became more and more pronounced in the work of both artists. Expressed both through composition and colour scheme, it created a surreal atmosphere. Some examples are Yakunchik- ova's “Interior with a Lamp", her “Lilies over the City" (consider the giant magical flowers) and “Vase by the Window", rendered in mysterious twilight. The artist's photo with a bouquet of lilies, as a prologue to the painting, emphasized the ephemeral mood of the piece.

Spending a lot of time with Yakunchikova in 1895 had a beneficial effect on Polenova, who told her brother's wife Natalia, Maria's older sister, that she and Yakunchikova shared tastes and views when it came to art, but Yakunchikova's craftsmanship and schooling were vastly superior.

Polenova was so inspired by Paris and its energy that she began to plan her next visit immediately upon her return to Russia. She really missed “that elevated and highly cultural feeling" that reigned supreme at Paris art exhibitions. She also missed the artistic fellowship she shared with Yakunchikova, who in 1896 married Leon Weber, a doctor, and consequently made less frequent trips to Russia.

In autumn 1897 Polenova decided to go abroad at the advice of her doctors, who ordered travel and rest. No one could have imagined that her brutal headaches, eye pain, and loss of movement in her legs were not the product of exhaustion, but symptoms of a brain tumor, the result of a head injury she sustained when she fell in April 1896. In the spring of 1898 Polenova, feeling somewhat better, happily accepted Yakunchikova's offer to work in her Paris studio. At the time, Polenova was involved in a variety of projects. For instance, she made sketches for the design of the Crafts Section of the Russian Pavilion at the upcoming 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, and engaged Yakunchikova in the project. Working both in Russia and in Paris, Polenova was also engaged in an enthusiastic collaboration with Alexander Golovin on a series of sketches for a “Russian dining room”, commissioned by Yakunchikova's brother for his country house in Nara, near Moscow.

The English journalist Netta Peacock was delighted with Polenova's design for the Nara dining room, and the artist's sketches for the decorative panels “Flowering Fern" and “Firebird", as well as numerous carving pattern designs, were published in The Artist, an English magazine that hailed them as a “truly national project" .

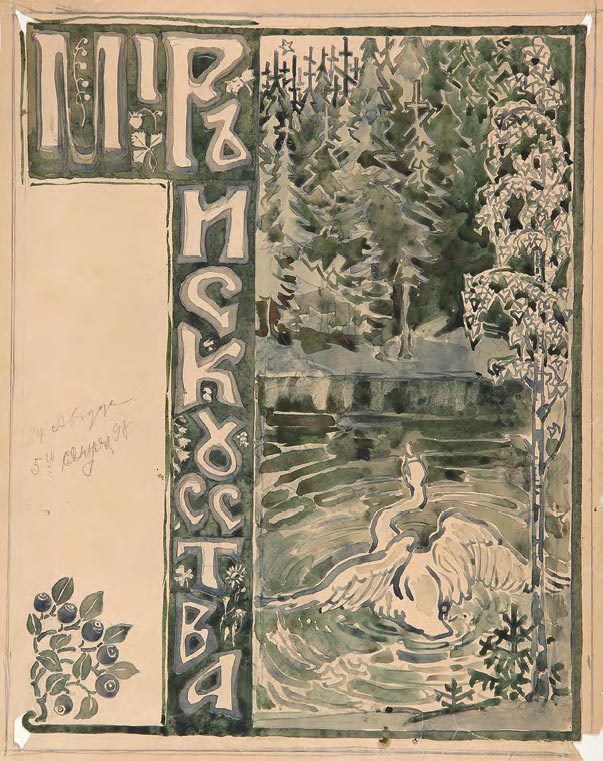

In April 1898, while in Paris, Polenova received Sergei Diaghilev's offer to work on his new magazine Mir Iskusstva. Polenova found the magazine's concept interesting and designed the cover for the first issue. Based on her recommendation, Diaghilev extended the same offer to Yakunchikova in the summer of 1898. When Polenova no longer felt she had the strength to continue the work, she urged her friend not to back out. For the magazine cover, Yakunchikova chose the image of a swan as the centre of the composition, symbolizing pure aspirations and tender poetic sentiments, and evocative of the beloved but lost family estate in Vvedenskoye (just like her “Columns. Balcony and Sketch of a Swan", 1897-1898.) When Polenova passed away, this image took on the significant of dual loss. In 1899 Yakun- chikova's watercolour - a stylized landscape framed in an ornamental border - graced the cover of the 18th issue of Mir Iskusstva, which was dedicated to Polenova's oeuvre in its entirety. In a brilliant move, Yakunchikova borrowed Polenova's signature style of fairy-tale illustration for this memorial publication.

Maria YAKUNCHIKOVA. Cover design for “Mir Iskusstva”. 1898

Watercolour and pencil on paper. 34.0 × 26.5 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Yelena Polenova died in November 1898. In her letter to Alexander Golovin Yakunchikova found incredibly touching words to express her grief: “you and I mourn her more than all others - without her, we are orphaned; there is no other way to describe how profound this loss is. [...] So there it is, she is gone, gone forever. Life no longer has any flavour; everything I hold most dear is connected to her."[23]

The connection between Yakunchikova and Polenova seemed to survive Polenova's passing, or rather Yakunchikova was unwilling to let it go. She took over Polenova's work on the design of the Crafts Section of the Russian Pavilion at the upcoming 1900 Paris Exposition. With boundless confidence in her role as her friend's artistic successor, Yakunchikova took the unprecedented step of using one of Polenova's illustrations for the fairy tale “Firebird" to create a large-scale fabric applique panel “Ivan the Fool and the Firebird", which was listed at the 1900 Paris Exposition under Elena Polenova's name. The work was a great success, along with Yakunchikova's panel “The Girl and the Woodsman". Decorative and symbolic, these works embodied the coveted synthesis of applied art and painting, and in them Yakunchikova fulfilled her and Polenova's vision of a new style in art.

After two brutally difficult years, Yakunchikova succumbed to her illness in Chene-Bougeries, near Geneva. She was 31 years old.

Even though Yakunchikova's life took her to Paris and Switzerland, her heart was in Russia and her beloved Vvedenskoye, the embodiment of her native land. She wanted to go home so much that “it hurt", and wrote in one of her letters: “If I ever paint again, it will happen in Russia."[24]

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova, April 18/30 1895//Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1218. Memorial Documents, Sheet 1.

- Diaghilev, Sergei. “European Exhibitions and Russian Artists"// Sergei Diaghilev and Russian Art. Moscow, 1982. V. 2, p. 56.

- Letter from Maria Yakunchikova to Yelena Polenova. October 28 1889//Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1160МД. Sheets 1-3. “quelle que chose de vague” (French): something indistinct, blurred.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Elizaveta Mamontova (Nelshevka) August 4, 1889// Sakharova, E.V. V.D. Polenov. Ye.D. Polenova. A Chronicle of a Family of Artists. Moscow, 1964. P. 433.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1223МД. Sheets 1-2.

- Letter from Maria Yakunchikova to Yelena Polenova. // Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1160МД. Sheets 1-3.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova. March 10 1894// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1217. Sheets 1-2.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova. May 23 1895// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1205МД. Sheets 1-2.

- Letter from Maria Yakunchikova to Yelena Polenova. May 28 1892// Sakharova, E.V. P. 484.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova. May 22 1892// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1223МД. Sheets 1-2.

- Wakana, or “young grasses", seven or sometimes eleven types of edible grasses, were picked in the winter or early spring. There was a tradition of giving friends gifts of young grasses picked on the seventh day of the first moon. The word also means “strength".

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova. May 22 1892// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1222МД. Sheets 1-2.

- Modest Alexandrovich Durnov (1868-1928) was a Russian watercolour artists, draftsman, architect, and poet. In 1888-1889 he studied at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, the painting workshop of Vasily Polenov. However, Durnov’s main achievement was in attracting talented artists and promoting innovative art. Thus, in 1895 his monograph on Pre-Raphaelites (Durnov considered them to be the forerunners of Symbolism and Art Nouveau) sparked an interest for this movement in Moscow's art world and the general public.

- Edward Coley Burn-Jones (1833-1898), an English artist and illustrator closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, a leading representative of the Arts and Crafts movement.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Natalya Polenova. Moscow, January 4/16 1895// Sakharova, E.V. P. 519.

- Polenova, Ye. D. Diaries and Autographs. Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 436МД.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Natalya Polenova. Moscow, October 30, 1895// Sakharova, E.V. P. 538.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova. December 31 1891/January 11 1892// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1221МД. Sheets 1-3.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova. April 1/13 1892// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1222. Sheets 1-2.

- Letter from Yelena Polenova to Maria Yakunchikova. June 1890// Tretyakov Gallery Manuscripts Department. F. 54. Item 1. D. 7348. Sheets 1-7.

- Letter from Maria Yakunchikova to Yelena Polenova. May 28 1890// Tretyakov Gallery Manuscripts Department. F. 54. Item 1. D. 9685. Sheets 1-5.

- Eghishe Tadevosyan Remembers Ye.D. Polenova// Yelena Polenova. Exhibition catalogue// Tretyakov Gallery. Moscow, 2011. P. 368.

- Letter from Maria Yakunchikova to Alexander Golovin. 1898// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1200МД.

- Letter from Maria Yakunchikova to Yelena Polenova. October 28 1889// Polenov Museum Reserve. Item 1160МД.

Oil on canvas. 31.6 × 23.7 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

© Manuscripts Department of the Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard. 20.2 × 27.3 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Photograph

Private collection

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard. 16.7 × 21.7 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard. 25.5 × 17.3 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Oil on canvas. 17.9 × 16.0 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Pencil, pen, ink on paper. 36 × 22.5 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Wood, carving. 60 × 52 × 23 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour on paper. 17.1 × 12.8 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Sketch of an illustration to the fairy tale “Son Filipko” (version of the fairy tale “Ivashka and a Witch”). Watercolour on paper. 26.2 × 18 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour, whitewash on paper. 31.4 × 26.2 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour, pencil, sepia on cardboard. 23.1 × 15.3 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Charcoal on paper. 61.0 × 47.3 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Etching on paper. 27.0 × 34.2 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Photographer K.Fisher

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Oil on canvas. 21.0 × 17.3 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Oil, pencil on canvas. 8.9 × 16.3 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Oil on canvas. 20 × 14.7 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Gouache on paper. 64.2 × 48 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

A Trip to the West in 1895. Watercolour on paper. 17 × 13.6 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour on paper. 154 × 95 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Pencil on paper. 15.5 × 8.5 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Oil on canvas. 33 × 40.4 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Pencil on paper. 32.6 × 24.9 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour on paper. 13.9 × 10.3 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour on paper. 34.2 × 24.0 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Oil on board, pyrography. 55.0 × 45 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Photograph. Private collection

Oil on cardboard. 29.3 × 22.8 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Oil on canvas. 31.2 × 24.5 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour on paper. 23.2 × 30.4 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour on paper. 23.2 × 27.2 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Pencil on paper. 10 × 6.2 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour on paper. 71.5 × 36 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

© Manuscripts Department, Tretyakov Gallery

Gouache, paper, cardboard. 50 × 65 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Ink, pencil on paper. 19.9 × 15.8 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Watercolour on paper. 15.8 × 27.8 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Illustration to “Ivan the Fool and Golden Apples”. Pencil, watercolour on paper. 59.6 × 64.0 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve