From the Golden Age to the Silver Age. THE CREATIVE ACHIEVEMENT OF VASILY POLENOV IN THE PRISM OF RUSSIAN CULTURE

“Polenov, everything he said and thought about art, and even his very manner, is tied to his works, and from the very beginning of his career seeing him transported me to his paintings. And everywhere, I see it in his art... how much he admired the beauty of the world, how happy beautiful shapes, and especially beautiful colours always made him.”[1]

Yakov Minchenkov

The Tretyakov Gallery’s new exhibition "Vasily Polenov”, running on Krymsky Val until February 16 2020, marks the 175th anniversary of the artist’s birth. Polenov (1844-1927) worked mainly in the final decades of the 19th century but the variety of his artistic activity establishes him as a key figure linking broader strands of Russian culture, not least through his influence as a teacher, contributing as he did to the development of the "Moscow school of painting” at the turn of the 20th century. Featuring more than 150 works drawn from 16 Russian museums as well as private collections, the exhibition brings Polenov’s monumental "Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery” from the Russian Museum to Moscow for the first time.

Oil on canvas. 75.5 × 62 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Vasily Polenov’s rich body of work includes exquisitely lyrical and emotional landscapes, an epic series of paintings on the life of Christ, historical canvases, portraits and genre compositions; set alongside his endeavours to create a synthesis of the arts that encompassed theatre, architecture and music, as well as his distinguished work as a teacher and theorist of art, it is an achievement that points to his deep connection to the spiritual quest of the Golden Age of Russian culture. At the same time, Polenov was one of the first Russian artists to embrace a new aesthetic worldview and with it the new artistic styles of Symbolism and the Art Nouveau, which would become hallmarks of the Silver Age.

Intertwined in Polenov's work were elements of romanticism, realist tendencies, the subtlety of the Russian mood landscape, and borrowings from Old Russian art; echoes of Western European romanticism and academic art combine with the painterly investigations of the Barbizon school and the Impressionists. It was a fusion that gave rise to a national version of the neo-romantic artistic worldview that provided the basis for Russian Symbolism and Art Nouveau. Those who shaped this new artistic movement, Polenov among them, were striving to create a single style of art that would envelop the people in pure beauty - and transform life accordingly: they brought about the brilliant achievements of Russian art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a time that has gone down in the history of Russian culture as the Silver Age.

But how could all this be part of the work of just a single artist, one who was often described as “complicated and inconsistent"?[2] Polenov has traditionally been assigned “a special place"[3] in Russian art of the 19th century and judged accordingly: it was no coincidence that in 1916, when the Tretyakov Gallery trustee Igor Grabar, himself a renowned artist and art historian, reorganized its permanent display according to the historical and logical development of Russian art, Polenov's works were hung in a separate hall. When Polenov asked Grabar to make an exception for his painting “The Patient" (1886, Tretyakov Gallery) and display it in the same hall as the works of his fellow artists from the “Peredvizhniki" (Wanderers) movement, Grabar answered: “I do understand why it is that you would want your ‘Patient' in the upper halls, with the works of your contemporaries. It is a shame that I did not take that chance when I was rearranging the galleries upstairs. There is nothing to be done now - not an inch of room to spare, to say nothing of hanging such an enormous painting. The hall with the works of the ‘Wanderers' is especially crowded."[4] We can certainly guess why Grabar did not “take that chance" to display Polenov's “The Patient" - the painting is sometimes called “Elegy", which conveys its meaning more completely - alongside works by the Wanderers. Though first presented to the public in 1886 at the 14th Exhibition of the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions, it did not fit within the natural confines of the Wanderers' genre. “The Patient" stands somewhat apart from the rest of Polenov's oeuvre, too, even though few of his other works express his immediate feelings and worldview quite as accurately as that one does.

“The Patient" is filled with a feeling of helplessness and bewilderment in the face of the tragic inevitability of death, its merciless and undiscriminating cruelty, one that strikes even those who are still young. It finds an unexpected resolution in the beauty of the counterpointing, second focal point of the painting, however: next to the exhausted face of the young woman, we see an exquisite still-life element, achieved through the most complex effects of colour and light. The rich and harmonious palette of the piece makes it possibly one of the most magnificent examples of 19th century Russian painting, a symbolic representation of the eternal beauty of the world by an artist who does not fail to recognize that quality even in the face of suffering and death.

A knight in the service of beauty

Polenov’s innate artistic talents were diverse, such versatility serving as the foundation for his work on a wide variety of creative endeavours. As a landscape painter, his ability to capture nature was so precise that it was described as “perfect vision" (in the same way that a musician is said to have “prefect pitch"); he was also a gifted decorative artist, an element that he channelled into his visual art as well as his stage design work, his decorative and applied art, and his achievements in interior design. At quite a young age, it became clear that Polenov was also a gifted architect, as his friend and fellow student Ilya Repin remembered in his memoirs: “We were still [students] at the Academy... when he began helping out some architecture students, his relations."[5] Polenov's talent for architecture was expressed in the architectural motifs of his landscapes, in his historical and genre paintings, and in architectural projects that were always original and innovative. His intuitively artistic nature gave Polenov a special feeling for and understanding of theatre, which saw him not only acting in and directing amateur theatre productions, as well as designing their sets, but also founding a new movement in Russian stage design and becoming a prominent figure in the Russian theatre world in general. A lover of music, Polenov had a fine singing voice and played the piano, and is the only major painter who was also a composer: he wrote symphonies and devotional music, romantic songs, quartets and operas, such as his “Ghosts of Hellas" and “Anne of Brittany". Music was a constant presence while he was painting too, which could not help but affect his art, in terms of both composition and colouristic approach: his uniquely melodious work was often described by viewers as “musical".

A pioneer in many forms, Polenov's “universal- ism" played a valuable role in the development of the new generation of Moscow painters who emerged in the 1880s and 1890s; indeed, he made an important professional commitment to them by taking on the extracurricular leadership of the landscape and still-life classes at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1882 to 1895. Many of Polenov's students spoke of his work, his teaching and of him as an individual with admiration, love and gratitude.

Young artists were particularly attracted by his personality: writing in his memoirs, Leonid Pasternak described Polenov as “the only true European gentleman and aristocrat, in the fullest and finest sense there is".[6] He was called by his contemporaries variously a “knight in the service of beauty" and “the ideal of spiritual nobility".[7]

Descended from several generations of the enlightened Russian gentry, into a family that preserved the best traditions of the Russian aristocratic intelligentsia dating back to the 18th century, Polenov seemed destined to bring together the qualities of early 19th century romantic art, the social involvement of the “Peredvizhniki", and the neo-romantic aesthetic of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Polenov’s great-grandfather on his father’s side, Alexei Polenov (1738-1816), has been called the “first emancipator of Russia”. A graduate of the University of St. Petersburg, he went on to study in Strasbourg and Gottingen, coming back to Russia “a man of broad and deep humanitarian education... [with] a profound knowledge of the philosophy and science of the 'Age of Enlightenment’.”[8] Soon after his return, Alexei Polenov wrote “On the State of Serfdom in Russia” (1766), the first publication in Russian history to criticize that institution and propose measures for the emancipation of the serfs. The artist’s grandfather Vasily Polenov (17761851) earned the deep respect of Russia’s great poet Alexander Pushkin, who knew him from his service in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and called him “a true scholar”. The artist’s father Dmitry Polenov (1806-1878) was an associate member of the Academy of Sciences, a renowned bibliographer, archaeologist and historian.

He was friends with many writers, musicians and artists, including the celebrated painter Karl Bryullov (1799-1852), whom he met in Greece, where in the 1830s Dmitry Polenov served as the Secretary of the Russian Mission in Athens.

The artist’s maternal grandmother Vera Voyeikova (1792-1873) played an important role in the early life and education of her grandchildren. The daughter of the famous architect, artist, writer and musician, Academician Nikolai Lvov (1751-1803), she introduced the young Vasily to the Golden Age of Russian culture, that which emerged in the first three decades of the 19th century. Orphaned at an early age, Voyeikova was raised together with her sisters by a relative, in the family of the poet and statesman Gavriil Derzhavin (1743-1816). She was married to Major General Alexei Voyeikov (17781825), who left her a young widow; later in life, when she brought her grandchildren to the Imperial Hermitage, she would show them their grandfather’s portrait (by George Dawe) among the other heroes of the Patriotic War of 1812 in the Military Gallery of the Winter Palace.

Voyeikova was a learned woman, a connoisseur of Russian and French literature, who knew Nikolai Karamzin, the author of the definitive 12-volume “History of the Russian State”, and could quote chapters from that monumental work by heart; she was also very fond of Russian poetry and folk tales. Polenov painted his portrait of his beloved “granny” in 1867, under the guidance of the famous artist Ivan Kramskoi, with whom Polenov took private drawing and painting lessons while a student at the Academy of Art in 1863-1871 (Kramskoi himself painted a parallel portrait of Vera Voyeikova at the same time).

Vera Voyeikova’s daughter Maria (1816-1895), mother of Vasily Polenov, was herself an amateur artist who also wrote children’s books, among them “Summer at Tsarskoye Selo”, a popular work that which was reprinted many times. Maria was taught art by Konstantin Moldavsky, a painter of Bryullov’s school, and she herself became her son’s first drawing and painting teacher. “I inherited a passionate love of painting from my mother,” Polenov would later say.[9]

As an artist, Polenov strove to bring benefit to the general population of his country and make a positive impact on the life of Russian society. This desire to bring art to the people was something that he shared with many other artists of the late 19th century, especially those of the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions with its democratic aspirations. Having become an active member of the Society in 1878, Polenov exhibited his works at the group's shows regularly. He saw his civic duty in both bringing aesthetic education to the masses and creating an art that would give rise to joy and beauty. As Polenov wrote in 1888 in a letter to his fellow artist Viktor Vasnetsov: “I think that art should bring joy and happiness, otherwise it has no worth."[10] It was a clear statement of Polenov's aesthetic credo, one that offers a key to understanding his work.

Landscape trilogy

The Tretyakov Gallery exhibition opens with three of Polenov's most renowned landscapes, “Moscow Courtyard", “Grandmother's Garden" (both 1878, Tretyakov Gallery) and “Overgrown Pond" (1879, Tretyakov Gallery), which can be considered something of a lyrical-philosophical trilogy. These paintings, first shown at the 7th and 8th Travelling Art Exhibitions, were well received by both the Society's artists and the general public, but it was young artists, those just starting their careers in the 1880s and 1890s, who proved particularly enthusiastic. One such figure, Ilya Ostroukhov, remembered visiting the “Peredvizhniki" exhibitions of 1878 and 1879: “One of the most unexpectedly joyful events was the discovery of Polenov's first informal landscapes at the very end of the 1870s. I was especially impressed by ‘Moscow Courtyard', ‘Grandmother's Garden', ‘Overgrown Pond', ‘By the Windmill', ‘Grey Day', and a number of other works; they reminded me of the intimate motifs of [Ivan] Turgenev - personal and informal, they surprised me with their novelty, originality, refined musical lyricism and exquisite technique."[11]

Vasily POLENOV. Moscow Courtyard. 1877

First version of the painting of the same name (1878, Tretyakov Gallery)

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard. 49.8 × 39 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

“Moscow Courtyard" introduced the practice of working en plein air to Russian art, not only as a painterly technique, but also as a heightened expression of the artist's union with nature. In Polenov's painting, the “plot" is “prompted" by the artist's poetic experience in the moment, when the beauty of this everyday scene, specific and unplanned as it is, strikes him unexpectedly. Various painterly and compositional techniques are worthy of note, used by the artist to create a profound and refined composition that reveals his most personal impressions of Moscow, in an image that is both historical and national: the poetry of a quiet, calm life in which profound truths about the national character, eternal and constant, are somehow expressed, albeit in a reticent manner. The painting's depth and humanity has come to enchant viewers, making it one of the most loved works of Russian visual art. The renowned collector Pavel Tretyakov purchased it straight from the exhibition.

Vasily POLENOV. Moscow Courtyard. 1878

Oil on canvas. 64.5 × 80.1 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

In a sense, “Moscow Courtyard" would herald a new understanding of the role that art should play in society, bringing us back to Polenov's words of 1888, “Art should bring joy and happiness, otherwise it has no worth." In “Grandmother's Garden" Polenov continued to explore the concept of harmony between man and nature, and found both new aspects of that theme and a new tone: as if skipping forward a decade, he expressed the lyrical contemplation and elegiac mood that would become so prevalent in Russian painting of the 1890s. It is a work that affirms the indissoluble link between different eras: the 18th century, with its elderly ladies, comfortable old mansions and shady gardens, lives on in the 19th. The unattended, lush park, with its ancient trees and young vegetation amplifies the intensity of the artist's images that anticipate the passeism, or nostalgia for the past, which would become so popular with the “Mir Iskusstva" (World of Art) artistic movement, with its characteristic admiration for the aesthetic of “times gone-by" and the “sunset glow" of the fading culture of the landed gentry. As a man of his time, however, Polenov provided a degree of “motivation" to explain the dream-like state of the two ladies in the painting: he emphasizes the age of the first figure, and gives the young one a book to hold. In contrast, the artists of the new generation would express such an “essence of sadness" through exclusively painterly means[12] (Viktor Borisov-Musatov, a student of Polenov, was one such figure).

Vasily POLENOV. Grandmother’s Garden. 1878

Oil on canvas. 54.7 × 65 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

The world that Polenov depicts is essentially a real one and might easily illustrate the poem “In the Garden" by Afanasy Fet: “I am so glad to see you, my dear old garden / Your blooms bequeathed from the blooms of my youth! / With a bitter smile on my lips, I smell your scents, / Which once filled the air of my childhood."[13]

“Grandmother's Garden" became simultaneously an homage by Polenov to the Golden Age and one of the first paintings to usher in the Silver Age of Russian culture.

The mood of the third work in Polenov's loose trilogy, “Overgrown Pond", is poetic and dreamy: the landscape's lyrical essence is clear thanks to a kind of “dialogue" between the old park and the pensive figure of the young woman, a perfect harmony of feeling. In the 1880s-1890s Polenov would go on to develop this new motif - of escape from the hardships of reality into the world of nature - and it will later become even more prominent in the work of Polenov's younger friend, the artist Mikhail Nesterov.

Vasily POLENOV. Overgrown Pond. 1879

Oil on canvas. 80 × 124.7 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

All three of Polenov's landscapes immediately became the focus of both public admiration and critical attention. A typical review, published in 1879, is indicative of such reactions: “The choice of subject [for ‘Grandmother's Garden' - E.P.] betrays a genre painter, not a landscape artist, and a romantic painter at that, insofar as any Russian painter can be romantic as it pertains to his works and images from Russian life... Similarly, ‘Overgrown Pond' is no ‘mere' pond... It is a pond with a story... Again, we see the work of a romantic in this painting... The Germans would call this composition Stimmungsbild, a painting that, first and foremost, strives to evoke in its viewer a certain mood; such works are the same to painting as elegies are to poetry."[14] The fusion of genre and landscape painting in Polenov's works of the late 1870s was a clear indication of a new phenomenon in Russian art, one that would become widespread towards the end of the century. This indicated a convergence of genres, with landscape painting taking on an important “substantive" role, a phenomenon later termed “genre landscapization" by the art historian Alexei Fyodorov-Davydov.[15] Polenov's landscapes are also a source for the “event-free" genre, the concepts of which would be later developed by the artist's students.

Polenov's impressive debut at the Society of Travelling Art Exhibitions was all the more unexpected since, nothing had seemed to predict any such breakthrough when he was studying at the Academy of Arts and later travelling in Europe on his Academy grant. The second part of the Tretyakov exhibition, dedicated to Polenov's work after he was awarded that grant, is testament to that.

Travels in Europe

Polenov received a thorough and wide-ranging education at both the Academy of Arts and the University of St. Petersburg. In 1871, he won the Academy's Large Gold Medal for his painting “The Raising of Jairus' Daughter" and received a grant to travel abroad, as did his friend and fellow Academy student Ilya Repin. At the same time, Polenov graduated from the University of St. Petersburg, having passed his final exams and defended an insightful and thoroughly researched dissertation on the development of the crafts movement in various European societies.

From 1872 to 1876 Polenov lived on his Academy grant while travelling in Germany, Italy and France, studying and assimilating in his own way the latest developments of Western European art. In Germany, he was especially captivated by the work of Karl von Piloty and other representatives of the classical-romantic movement in historical painting; at the same time, he was engrossed with the work of Arnold Bocklin and Hans Makart, whose work anticipated the neo-romanticism of the Art Nouveau. The years that Polenov spent in France coincided with the appearance of the Impressionists and their exhibitions that provoked controversy and caused considerable discussion in artistic circles. Impressionist art gave Polenov another reason to explore painting en plein air, and for that purpose he and Repin travelled to Veules, a small town in Normandy where they shared a house from July to September 1874. During those six weeks Polenov created a series of excellent landscapes and studies, including “White Horse. Normandy" (Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve), “Fishing Boat. £tretat. Normandy" (Tretyakov Gallery), “At the Park. Veules, Normandy" (Russian Museum), and a study for that work, “Old Gate. Veules. Normandy" (Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve).

In Paris, Polenov and Repin were frequent guests of the artist Alexei Bogolyubov, whose house was a gathering place for Russian artistic circles in the city. On the jour fixe, Bogolyubov opened his doors to artists, who would come to make prints and ceramics, spend the evening reading aloud, staging tableaux vivants and playing music. According to Repin, Polenov, a “sociable and cheerful man", took an active role in such pastimes.[16] Ivan Turgenev was a frequent guest, too, and meeting the venerable writer at Bogolyubov's home played an important role in Polenov's life. Turgenev clearly liked the young artist and eventually introduced him to the famous opera singer Pauline Viardot, whose salon brought together major writers, musicians and public figures, among them the writer £mile Zola and the historian of religion and philosopher Ernest Renan. Renan, his conversation and his book “The Life of Jesus", which had been published in Paris in 1863, would play a crucial role in shaping Polenov's plans to paint Christ and scenes from the New Testament, which came to fruition in his series “From the Life of Christ" (late 1890s-1900s).

During this time Polenov conceived of, and started painting a range of historical works, but finished only two of them, “The Right of the Master (Droit du seigneur)" (1874, Tretyakov Gallery) and “Arrest of the Huguenote Jacobine de Montebel, Countess d'Etremont" (1875, Russian Museum). Both of these paintings were executed in the late Western European academic style of historical painting, reminiscent of von Piloty, Paul Delaroche and Louis Gallet: Polenov tried to achieve a special historical accuracy and had a particular interest in literary and romantic subjects, which he presented in a somewhat theatrical manner.

Upon his return to Russia in 1876, Polenov exhibited in the Academy's halls the creative result of his travels in the form of six paintings and 50 studies, and was awarded the title of Academician. Encouraged, he decided to approach the renowned art and music critic Vladimir Stasov to ask his opinion of the works shown at the Academy. Stasov praised “the two most important strings" of Polenov's talent, “colour and grace", but rebuked the artist for being “too Frenchified". Having concluded that “the constitution of [Polenov's] soul was not at all Russian", Stasov advised the artist that he “would be better off living permanently in Paris or Germany".[17] The critic was right when he said that Polenov's paintings, with their “many elegant and refined details... very pleasant and graceful", were highly influenced by Western European art.[18] It is an entirely different matter that Stasov could not imagine that such a painterly technique could work for a truly Russian artist.

In his verdict on Polenov's works, Stasov unintentionally tapped into an urgent problem facing the artistic community of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: the challenge of preserving the national identity of Russian art while interacting with the artistic and cultural movements of Western Europe. Polenov's works of the late 1870s proved testament to the great potential of just such an interaction.

At intervals during his years abroad, and immediately after his return home, Polenov spent time resting at his family estate of Imochentsy in the Olonets Governorate. It was an ideal place for him to immerse himself in the life of the Russian peasantry, and it was there that Polenov learned to understand and appreciate the work of folk craftsmen and artists. Though sparsely populated, the villages of the region preserved the distinctive features of the wooden architecture of the Russian North: it was there, in the 1870s, that Polenov painted his landscape “Sugar Hill in Winter" (1870s, private collection), depicting peasant log houses against a backdrop of the severe northern nature. Polenov was also introduced to the oral folk tradition and other kinds of local folklore: when scholars later started visiting the region to record them, the folk songs and epic poems, or byliny, of the Olonets storytellers would become exceedingly popular. Polenov's portrait “Nikita Bogdanov, Narrator of Folklore (Byliny)" (1876, Tretyakov Gallery) introduces the viewer to such a “man of the people", one “blessed with a natural mind and a common good sense": he is a figure very much like the characters of Turgenev's “Sketches from a Hunter's Album", or the subjects of Ivan Kramskoi's peasant portraits.

Following his return to Russia, Polenov joined the Russian volunteer army to fight in the Serbian-Turkish War. For his military service, he was awarded a medal and a commendation, while the drawings he made at the front were published in “Pchela" (Bee) magazine: most of them were scenes of “bivouac life", alongside ethnographic and architectural sketches. In 1877-1878, as a staff artist on the Bulgarian front of the Russo-Turkish War, Polenov once again painted military life: as in Serbia, his most interesting works were drawings and small oil studies depicting the everyday activities of soldiers and local people alike. Polenov would not become a military artist in any official sense.

Abramtsevo and a synthesis of the arts

The industrialist and patron of the arts Savva Mamontov would play an important role in Polenov's “self-discovery" as an artist. The two had first met and become friends in the early 1870s, initially when Polenov was living in Rome, then later in Paris, a city that Mamontov visited periodically; their friendship blossomed when Polenov returned to Moscow in 1877. According to Nikolai Prakhov, son of the art scholar Adrian Prakhov, Mamontov and Polenov were brought closer by “their mutual interest in art in all its forms, including painting, sculpture and theatre. Both were devoted to art."[19]

It is easy to imagine Polenov, whose paintings are so reminiscent of Turgenev's quintessentially Russian prose, at Abramtsevo: it was a classic Russian country estate of the second half of the 18th century, the home of the famous writer Sergei Aksakov from 1843 until its acquisition by Savva Mamontov in the mid-1870s. Polenov's oeuvre is rich in images of Abramtsevo and its surrounding areas: he painted dozens of studies and landscapes there, including “Birch Alley in the Park" (1880) and “The Upper Pond at Abramtsevo" (1882, both at the Abramtsevo Museum-Reserve). Polenov's Abramtsevo landscapes reflect his new connection, personal and poetic, to nature, one that no longer required the presence of any human “intermediary". The artist used larger and more generalized painterly forms, even though he was still fond of his favourite mysterious romantic “corners" and the interplay “game" of planes that often pile up on one another (“Abramtsevo. The Vorya River", 1882, Abramtsevo Museum-Reserve). The principles of plein air painting are less pronounced in these landscapes, with colour consequently becoming much more resonant. The perfect embodiment of this type of landscape is Polenov's painting “Autumn in Abramtsevo" (1890, Abramtsevo Museum-Reserve), which the artist would finish at Borok, the estate on the Oka river outside the town of Tarusa, which he purchased at the end of 1889.

In the late 1870s Mamontov brought together at Abramtsevo some of the major Russian artistic figures of the time, including Polenov and Repin, Viktor Vasnetsov and the sculptor Mark Antokolsky, who were joined in the 1880s and 1890s by younger artists such as Valentin Serov, Konstantin Korovin, Yelena Polenova, Mikhail Vrubel, Mikhail Nesterov, Apollinary Vasnetsov, Ilya Ostroukhov and many others. Polenov himself first visited in 1873, while he was still living abroad for most of the year on his Academy grant. It was there that he met Mstislav Prakhov: the older brother of the art historian Adrian Prakhov, he was a poet, philosopher and linguist, a romantic and follower of Friedrich Schelling. Mstislav spent much time at the Mamontov estate, and Polenov's own aesthetic ideas found confirmation in Prakhov's theories: their most important practical application would be in the work of the Abramtsevo theatre, which was established on Prakhov's initiative. Polenov created romantic and inspiring stage designs for its productions, while also becoming one of its star performers: it was easy for him to “get into" characters whom he found close to his heart, such as Decius in Apollon Maykov's “Two Worlds", the embodiment of the heroic, romanticized spirit of antiquity, or Camoens in Vasily Zhukovsky's eponymous drama (1882), a retelling of the play by the Austrian romantic writer Eligius Franz Joseph von Munch-Bellinghausen. In the latter work, Polenov played the role of an impoverished and dying poet, who challenges the unappreciative mob and wins a spiritual victory over them.

The part of the exhibition dedicated to Polenov's amateur theatre work presents set designs such as “Atrium" for the first production at the Abramtsevo theatre, “Two Worlds", in 1879: the design combined the precisely reconstructed state rooms of a patrician house of Ancient Rome with a significant degree of generalization and symbolism that was driven by the specific nature of the Abramtsevo theatre space. In his work on the “Atrium" design, Polenov drew not only from his knowledge of Roman architecture and his artistic talent, but also from his acting experience and his deeper understanding of Maykov's drama. As a result, a new synthesis of the arts was born: viewers who saw “Two Worlds" were fascinated by the production's “artistic seamlessness", and its moments when, according to Viktor Vasnetsov, “beauty and true poetry came together."[20]

Vasily POLENOV. Atrium. Act III. 1879

Study for the set design for Apollon Maykov’s “Two Worlds” on the home stage at Abramtsevo. Premiered on December 29 1879 in Moscow. Watercolour on paper. 10 × 15 cm

© Abramtsevo Museum-Reserve

Polenov's experience of acting on stage - a small stage, in this case - inspired him to create a simpler set, with neither a curtain nor complicated scenic rearrangements; he introduced a theatre cloth that framed the painted backdrop canvas that “illustrated" the main theme of the design. The result was the so-called “single picture" principle, an approach that allowed Polenov to make use of his expertise as a painter in the service of set design, with an emotionally powerful and all-encompassing result. Skillfully modifying and “sharpening" a variety of architectural forms, Polenov created highly eloquent imagery in such stage work. Thus, he renders the atmosphere of a gloomy hospital in medieval Lisbon by using the decorative potential of simple and laconic vaulted ceiling shapes (in “Hospital", a study for the 1882 production of Zhukovsky's “Camoens"), or evokes the expressive side of Ancient Egyptian architecture in his study “The Dungeon" for “Joseph" (1880), a play by Mamontov himself (both works at the Abramtsevo Museum-Reserve). Polenov's greatest achievement in his set design for these amateur theatre productions was his work on “Scarlet Rose" (1883), another work by Mamontov, where the artist's painterly style was transformed.

Those involved in these home theatre productions took collective decisions about each work, scheduling issues and the structure of the Abramtsevo artistic commune as a whole: they shaped the personal relationships and professional contacts between its members, and more or less determined the position of each within the community. One testament to that is the fact that members of the Abramtsevo artistic commune considered 1878, the year that the first evening of amateur theatre took place in Mamontov's house on Sadovo-Spasskaya Street in Moscow, as the date of the founding of the Abramtsevo colony: thus, they marked the 15th anniversary of its existence in 1893. After that celebratory event, they decided to publish an illustrated commemorative album, titled “Chronicle of Our Artistic Circle", with Mamontov and Polenov responsible for its contents.[21] In 1894, Polenov created the front title page for that album, depicting the entrance to a room, which looked a little like the interior of Mamontov's study. However, on the whole the image is symbolic, not representational: it speaks of a place where beauty reigns and is revered.

The role that theatre played in the life of the Abramtsevo artistic colony is in some way analogous with the overall theatrical atmosphere that permeated the art and culture of the Silver Age, when life, art and theatre came together to create the belief that the world itself is a theatre, resulting in a “theatricalization of life and art", in the words of the director and dramatist Nikolai Efreinov.[22]

Such amateur theatre at Abramtsevo provided valuable experience for Savva Mamontov's Russian Private Opera, which was established in 1885: its first productions proved a real sensation thanks to their rare artistic merit, as well as the fine interplay between the stage design and the creative production, music and writing. Polenov introduced his students, graduates of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture - among them Isaak Levitan, Alexander Yanov, Nikolai Chekhov, Viktor Simov and Konstantin Korovin - to Mamontov and his theatre. Polenov was one of the first of many easel painters at Abramtsevo to turn to theatre set design in the late 1870s and 1880s, initiating a movement that not only contributed to these extraordinary achievements in the art of stage design, but also gave rise to a revolutionary new phenomenon in Russian art, which would later be called the “theatricalization" of painting.

Polenov and Mamontov worked together on two theatrical productions in the 1890s: the tableau vivant “Aphrodite", for which Polenov created the sets and composed the music - it was staged in 1894 at the Assembly of the Nobility during the 1st Artists' Conference - and a theatre performance, an adaptation of Gluck's “Orpheus and Eurydice" at the Russian Private Opera in 1897. According to Polenov, both of these projects, connected as they were with the art of antiquity, brought him “special satisfaction". Nikolai Prakhov, who grew up as a child in these circles, wrote in his memoirs that Polenov, in cooperation with Mamontov, the author of the scenario for “Aphrodite", created “a spectacularly stylish, beautiful and dynamic production. Its theme was the celebration of beauty."[23] Polenov's approach to stage design was conditional enough to create an idealized image of Greece, with its architectural monuments, plasticity and nature, cleansed of anything that hinted at the everyday. With some modifications, the same scenic composition was used for the 1906 amateur production of the opera “Ghosts of Hellas" (with libretto by Morozov) at the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory. “A rare example of artistry, a glimpse of antiquity brought back for one night before an enchanted 20th century audience," one critic wrote.[24] (An abridged version of the opera was staged at the Townsfolks' House in Tarusa in 1915.) In the 1900s Polenov used his studies for the sets of “Aphrodite" to paint “Hellas" (also known as “Ancient Greek Landscape", now in a private collection): the artist based the background on a study from nature, while executing the forefront in a decorative style. This motif became very popular with art aficionados and collectors, and Polenov went on to paint several versions of the work.

From the article “Polenov’s Musical Creations”*

Marina Rakhmanova

* Rakhmanova, M.P. ‘Polenov’s Musical Creations’ // ”Vasily Dmitrievich Polenov in Russian Art and Culture of the Second Half of the 19th and Early 20th Centuries”. Moscow, St. Petersburg, 2001. P. 73.

It is well known that music played a very important role in the artistic outlook of Russian artists of the 19th and early 20th centuries: among them were figures such as Mikhail Vrubel and Ilya Repin, a passionate enthusiast of contemporary Russian music, while others were amateur musicians who could play various instruments. However, only one major Russian painter was known to compose music on a regular basis - Vasily Polenov.

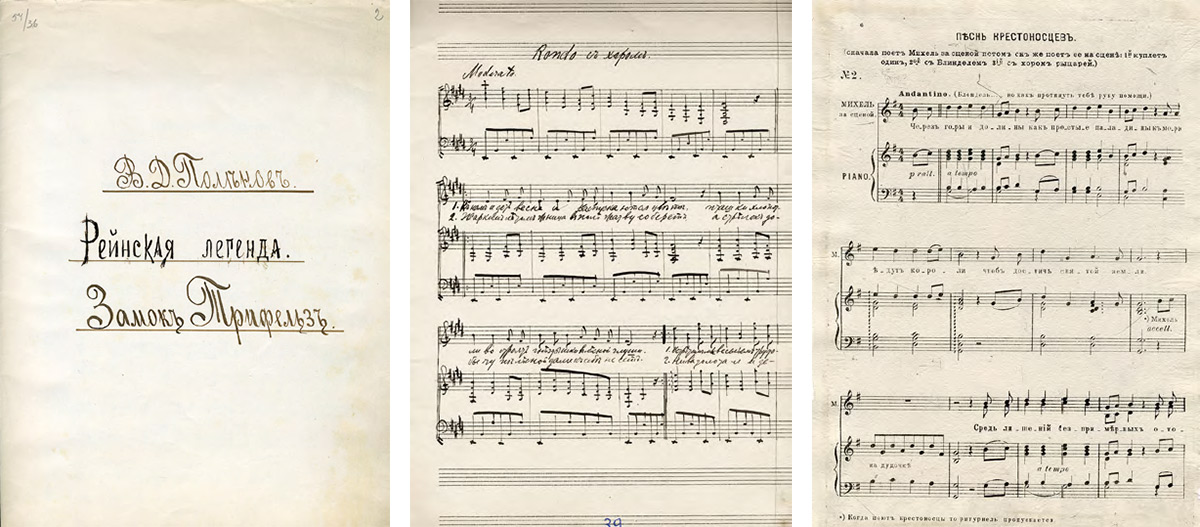

Proof-sheets of the opera “The Legend of the Rhine. Trifels Castle”. Author of the libretto Savva Mamontov, composer Vasily Polenov. c. 1917

© Department of Manuscripts, Tretyakov Gallery

His music should be assessed in the light of the close organic connection between his musical aspirations and the goals he pursued in painting and the other spheres of his artistic activities. Thus, his opera “Ghosts of Hellas", his best-known musical work performed in public, now appears inseparable from the themes of Classical Antiquity that he developed in his paintings, as well as in his work on the design of the Antiquity Halls at the Alexander III Museum of Fine Arts (now the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts). Polenov's goal as a composer in the opera was the same as that which he pursued when he worked on the interior design of those museum spaces - to communicate the effect that the art of Ancient Greece had on him, the impression of “something living and breathing, which is, for some reason, called classical, and therefore [feels] cold" [the phrase is a quotation from the artist Valentin Serov].

In “Ghosts of Hellas", Polenov's musical endeavours are aligned with the “classical", “ontological" motifs to be found in the works of the leading Russian composers of his time, such as Sergei Taneyev in his opera “Oresteia" and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (in his opera “Servilia" and the cantata “From Homer"), as well as the romantic songs of the late 1890s and early 1900s. As is often the case with “second- and third-tier" artists - to which ranks, Polenov definitely belonged as a composer - such works are much more representative of general cultural and artistic tendencies than are the creations of major artists, which are more personal and distinctive. From this point of view, Polenov's “Ghosts of Hellas" offers interesting material for analysis as part of any study of how Russian society of his day perceived classical themes in art.

When, in 1897, Mamontov was considering staging “Orpheus and Eurydice’’, he wrote to Polenov that he had “high hopes" for it and was intending to teach the Moscow public “a lesson in aesthetics".[25] In this letter Mamontov described his vision of the stage design: “Scene IV... We need an impressive ravine (something like Bocklin)...’’[26] Polenov, who in his youth had admired the work of Arnold Bocklin, came up with the design sketches “Ravine in Rocky Mountains" and “Cemetery with Cypresses" (both at the Bakhrushin Theatre Museum, Moscow), which were evocative of Bocklin's symbolist paintings, although the style of the Art Nouveau is already emerging in them more strongly.

Polenov's engagement with architectural projects in the early 1880s seems natural within the Abramtsevo commune. Alongside other artists, he was captivated by the idea of building a church there, participating in its design, construction and interior decoration: he proposed to build it in the style of 12th century Novgorod, a novel concept in itself for the 19th century, when church architecture looked to the mid-17th century cathedrals of Moscow as the preferred standard. In that choice, Polenov offered the proponents of the Russian Revival (Neo-Russian) style in architecture a “new aesthetic ideal".[27]

Many of the main principles of the Art Nouveau in design were also set at the Abramtsevo workshops, which were established at the time. Among them were the carpentry workshop, led by Yelizaveta Mamontova and Yelena Polenova from 1885 to 1893, and then from 1908 by Maria Yakunchikova and Natalya Davydova, and that devoted to ceramics, led by Savva Mamontov and Mikhail Vrubel, which functioned at Abramtsevo from 1890 to 1895 before it was moved to Moscow, where it continued until 1918.

Abramtsevo's “cult" of beauty and joyful creative work in no way excluded the concept of serving the people that was so dear to the hearts of the Russian intelligentsia in the era that followed Alexander Il's 1860s “Great Reforms", especially among the older generation of the Abramtsevo artists, Polenov, Viktor Vasnetsov, the sculptor Mark Antokolsky, and Savva and Yelizaveta Mamontov among them. However, this idea would undergo a distinct transformation: such service to the people was now seen as, first and foremost, a matter of bringing beauty into public life. Mamontov expressed this concept in a striking aphorism: “We are indebted to the people. Art, in all its forms, has to be for the people. We must make sure that the people become accustomed to seeing beauty at railway stations, in churches, and on the streets."[28] The idea of changing the world according to the laws of beauty would give a lofty meaning to Abramtsevo's involvement in all kinds or art, the purpose of which was to “make life beautiful".

Polenov's experience working at Abramtsevo would eventually contribute to the unique architectural and park ensemble which the artist created at his Borok estate on the River Oka, which today accommodates the Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve (the Vasily Polenov Memorial Art and History Museum and Nature Reserve). The Big House there was designed by the artist and built in 1892 to accommodate a museum and picture gallery: it brought together painting and architecture, the decorative arts and theatre, a natural union that was close to a synthesis of the arts, the stylistic harmony that the artist pursued in his work. A stylistically integral artistic image was similarly created by Polenov in his two other architectural projects at Borok, “the Abbey" (1904), which served as his studio, and the Holy Trinity Church in the village of Byokhovo (1906), which he built for the local residents. All of these buildings were executed in the style of the Art Nouveau: Polenov called his architectural style “Scandinavian", although the influences of the Romanesque and Gothic can also be detected among the foundations of the imagination of this romantic artist. However, the most accurate description of the style of these buildings is simply the “Polenov style", a phrasing that reflects the artist's original and profoundly innovative approach to architecture.

Polenov's experience at Abramtsevo would also inform his work on the promotion and development of the concept of “theatre for the people", an interest and involvement that became especially strong towards the end of his life. In 1915, Polenov designed and partially financed a building to house the “Association for Furthering the Development of Rural, Factory and School Theatres", the House of Theatre Education on Medynka Street in Moscow, the architecture of which was a reflection of Polenov's love for the cultural heritage of medieval Europe. The artist devoted a great deal of his creativity and energy to the work of the organization - he saw theatre as a “great cultural endeavour", one that reflected the ancient credo, artes molliunt mores. In 1921, when the organization was nationalized, the building was renamed the “Vasily Polenov House of Theatre Education".

Any study of the breadth and variety of Polenov's talents raises two major questions. Was the artist's painting style influenced by his work in architecture, theatre, and the applied and decorative arts? And, conversely, how did Polenov's decorativism reveal itself in his easel paintings?

The emotional power of colour in Polenov's painting first became apparent to viewers at the 13th “Peredvizhniki" exhibition where he showed his studies for the painting “Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery" (also known as “Christ and the Sinner", sometimes supplemented by the subtitle “He that is without sin among you", 1887, Russian Museum), which originated from his journey to the Middle East in 1881-1882. Ilya Ostroukhov wrote about the impression that these studies made on him: “This was something filled with a sincere excitement at the colouristic beauty, while at the same time finding a way to solve colouristic tasks that was entirely new and unusual in Russian art. In these studies Polenov revealed the mystery of a new power of colour to Russian artists, stimulating them to use it in a way they could never previously have imagined."[29] However, it was not only the beauty of Polenov's art that influenced this new artistic generation: having mastered the study as a multi-faceted and far-reaching form in itself, he effectively opened new artistic horizons to his young colleagues.

Teacher of the new Moscow school of painting

In the early 1880s Polenov had the opportunity to directly influence the artistic education of the young, as he began teaching at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture in autumn 1882: he replaced Alexei Savrasov as the head of the landscape class at the School, and also taught the optional discipline of still-life painting, continuing in both capacities until 1895. His classes had an atmosphere of sincere, trusting good-fellowship, and his students applied themselves zealously to the study of drawing and the techniques of painting. Step by step, Polenov introduced them to the secrets of colour and perspective, of which he himself had superb command, as he applied the rules of linear and aerial perspective in his works. In his teaching practice Polenov essentially continued to apply the principles that he had been taught in his own childhood by Pavel Chistyakov. [30] (Much later, in a 1924 letter congratulating Polenov on his 80th birthday, his erstwhile student Mikhail Nesterov recalled: “One of Chistyakov's best students, you passed on his artistic credo to your students.")[31]

Students and teachers of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture Vasily Polenov (in the first row, left), Vladimir Makovsky (in the second row, seated), Yegishe Tatevosyan (in the third row). Photograph. 1891-1892

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

Polenov believed that “there is nothing you can teach young people who have been through the general classes; all they need is just the opportunity to continue to study,"[32] and such a liberal approach helped each of his students to maintain his or her distinctive painting style. Polenov thought it absolutely necessary for young artists to learn from the achievements of Western European art: another student, Konstantin Korovin reminisced that it had been Polenov who first told him and Levitan about the Impressionists and the Catalan painter Mariano Fortuny, introducing them to such art.

Polenov's close contacts with these young artists, who rejected “ideology" in art off-hand to proclaim instead its independent value, made his divergence from the “Peredvizhniki" increasingly noticeable. Not only had he never shared the stance of the older generation of the Wanderers that spoke against the slogan “art for art's sake", he was in fact in the opposite camp when it came to this pivotal theoretical issue.

Polenov's students soon felt in their element at his home on Krivokolenny Lane, where they gathered, first in small groups and then later in greater numbers, as Polenov began to host regular painting and watercolour evenings, first on Thursdays and then on Saturdays too. Artists from the older generation, among them Viktor Vasnetsov, Vasily Surikov, Nikolai Nevrev and Alexander Kiselev, worked alongside Polenov's students, such as Konstantin Korovin, Alexander Golovin, Isaak Levitan, Abram Arkhipov, Sergei Ivanov and Sergei Vinogradov, and their friends, including Ilya Ostroukhov, Valentin Serov, Mikhail Nesterov, Alexei Vasnetsov and Mikhail Vrubel. The “delight and benefit", in Yelena Polenova's words, of these gatherings was that “they brought together people plying the same trade. Sharing impressions and ideas was more important than the work itself."[33]

One of those who attended these gatherings, Leonid Pasternak, later wrote in his memoirs: “It's perhaps difficult now to imagine the oasis... that the house on Krivokolenny was,[34] and how the influence of Polenov's artistic personality flowed through it and spread around Moscow, and beyond it as well. It was also thanks to that influence, and his active participation, that the memorable regular exhibitions in Moscow flourished and attained quite a high level."[35]

The year 1893 saw the establishment of the Moscow Society of Artists, in whose activities Polenov and many of his students took part. The chief distinguishing factor in the shows of this group was their combination of interest in Impressionism with a search for a “decorative element".[36] The characteristic experimentation of these Moscow artists in the decorative arts, stemming from their interest in folk traditions, harked back to the Abramtsevo community of artists, when Vasnetsov and Polenov were creating their first pieces in this style.

Sergei Diaghilev first saw the works of these young Moscow artists in 1897 at an exhibition of the “Peredvizhniki", writing in his review of the show of a “young Moscow school which has injected our art with a completely new spirit". “It is from this small group of people, from this exhibition," Diaghilev continued, “that one ought to expect the movement that will win us a place in European art."[37] In 1898, Moscow artists such as Korovin, Sergei Malyutin, Nesterov, Levitan and Yelena Polenova were already taking part, alongside their St. Petersburg fellows, in one of Diaghilev's earliest projects, the “Exhibition of Russian and Finnish Artists". The appearance of a new concept - the new Moscow school of painting - in Russian artistic life was to a great extent the achievement of Polenov, as both an artist and an educator. Isaak Levitan rightly noted in a letter to Polenov on November 22 1896, “I'm certain that without you the art of Moscow would not be what it is today."[38]

Polenov's eagerness to help the new generation extended beyond the immediate circle of his students, too. It is well-known that the period in which Mikhail Vrubel was working on his two panels - “The Faraway Princess (Princess of Dreams)", inspired by Edmond Rostand's play of the same name, and “Mikula Selyaninovich", inspired by the epic tale about Volha and Mikula - was a challenging one for the artist. The huge pieces, commissioned by Savva Mamontov, were intended to decorate the interior of the Arts Department of the Russian National Art and Industry Exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod in 1896, but a committee set up by the Academy of Arts rejected them before they had even been finished: Vrubel's imagery, the committee members believed, was too innovative. Indignant at the Academicians' decision, Mamontov purchased the murals on their completion and later displayed them in a specially organized space near the entrance to the exhibition. As Mamontov requested, both compositions were completed by the artists Polenov and Korovin under Vrubel's supervision - such a condition was put forward by Polenov - who was at that time creating a decorative mural for Morozov's town mansion. Thus, many people had the chance to familiarize themselves, before visiting the 1896 exhibition, with the work of the talented but little known artist. Polenov, by then a professor at the Academy and an acclaimed artist in his own right, undertook to finish the panels in the capacity of a rank-and-file executor of instructions because, as he wrote to his wife, “They [the panels] are so talented and interesting that I could not resist."[39]

Always receptive to new tendencies in art, Polenov showed himself more eager than his contemporaries to learn about current developments - and he did indeed learn from his students and from young artists such as Serov, Korovin and Levitan, while nevertheless retaining his distinctive qualities and preserving his “Polenovian" mood and attitude.

Gospel themes

The section in the Tretyakov exhibition focusing on Gospel themes in Polenov's art opens with his Academy graduation composition “The Raising of Jairus' Daughter" (1871, Museum of the Academy of Arts). Addressing the Gospel story of this miracle of healing, Polenov wanted to lend the piece a sublime air and produce a composition in a solemn style. Working on the image of Christ, he was obviously following on from the august and monumental figure of Alexander Ivanov's composition “The Appearance of Christ Before the People" (completed in 1857). At the same time it is clear that Polenov was keen on conveying the states of mind of those present at the scene with a realistic accuracy, and portraying a “historically faithful" environment: it was in such concerns that he departed from Ivanov's approach to painting Gospel subjects.

In his early years, impressed by Ivanov's composition, Polenov had dreamt of becoming a successor to the great painter and picturing a “Christ, who is not only bound to come but who has already come to earth, and is following His path among the people."[40] Polenov had first heard about Ivanov from a close friend of his father, Fyodor Chizhov, who lived in Rome; a neighbour of Ivanov, Chizhov often visited him in his studio. Soon, at the Academy of Art exhibition in 1858, the 14-year-old Vasily saw for the first time “The Appearance of Christ": it left an indelible impression on him.

Polenov's dream came closer to realization in 1868 when, during his studies at the Academy, he contemplated producing the composition “Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery" (1887, Russian Museum). The painting's theme accorded with the artist's desire to depict the moral strength and triumph of the humanistic ideas of beauty and truth that Christ brought to the people. Polenov worked on the first sketches and studies for the picture in 1872 and 1876, during his travels in Europe, before re-engaging with the idea of the painting in the early 1880s, when he set about serious work on it, becoming entirely preoccupied with the project for the next six years.

In keeping with the approach of Ernest Renan, who believed that Jesus was a real person, Polenov argued that it was necessary “to present His living image in visual art too, to present Him such as He was in reality". [41] Eager to depict a historically faithful environment, Polenov travelled in 1881-1882 to Egypt, Syria and Palestine, visiting Greece on the way. From the very start, his preparatory sketches were not at all like ordinary rough drafts. They do not look like preliminary drawings of an environment: each of the sketches features a compelling image, as in “The Nile at the Theban Range" (1881), “The First Rapid on the Nile" (1881) and “The Ruins of Capernaum" (1882, all at the Tretyakov Gallery). Sketching architectural landmarks, Polenov was interested in the integral quality of the image, striving to portray the interconnection between landmarks and the landscapes around them, to convey the medium of air and light in which they seem to be “immersed": such works include “Haram Ash-Sharif" (1882) and “The Temple of Isis on the Island of Philae" (1882, both at the Tretyakov Gallery), and “Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem" (private collection). On this, his first journey to the Orient, the artist spent much less time sketching people than he did capturing landscapes and architectural landmarks. However, Polenov did pay attention to the distinctive gestures of those he encountered, including how they wore their clothes and their colourful combinations of costume, as in “An Arab Boy. A Guide in Cairo" and “A Donkey Driver in Cairo" (1882, both at the Tretyakov Gallery).

Polenov's painting skills became more diverse. He used pure colours, refrained from mixing paints on

the palette, and created felicitous colour combinations directly on the canvas, achieving astonishingly powerful hues. Thanks to his profoundly individualized responses to architecture and scenery and his ability to infuse them with strong emotion, the artist was able to achieve an almost symbolical quality in some sketches. A case in point is “An Olive Tree in the Garden of Gethsemane’’ (1882, Tretyakov Gallery), with its image of a fancifully shaped tree which seems to be a reincarnation of the long history of the land from which it grows; other such images are “The Parthenon" and “Erechtheion. Porch of the Caryatids" (both 1882, Tretyakov Gallery), which convey Polenov's characteristic delight in, and admiration for the harmonious, august world of antiquity.

Vasily POLENOV. An Olive Tree in the Garden of Gethsemane. 1882

Oil on canvas. 30.1 × 23.7 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

The fact that the sketches were works of art in their own right was highlighted when they were displayed as a series at the 13th “Peredvizhniki" exhibition in 1885: Pavel Tretyakov bought them in their entirety directly at the show. Polenov continued to work meanwhile on “Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery": he spent the winter of 1883-1884 in Rome, depicting the local Jewish population and refining his sketches. In 1885, on a country estate near the town of Podolsk where he spent the summer, Polenov finished a charcoal drawing on a canvas which was the size of the future composition (Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve). The careful finish of that drawing bears witness to the artist's desire to enhance the dramatic quality of the scene: graphic art, given its economy of line and faithfulness in rendering the idea of the work, proved the right medium. The painting itself was created in 1886-1887 in Moscow, in Savva Mamontov's study in the house on Sadovaya-Spasskaya Street: some 15 years had passed between the first sketches of 1872 and the completion of the work.

Vasily POLENOV. Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery. 1885

Charcoal on canvas. 307.7 × 585.5 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

“Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery" was first shown at the 15th “Peredvizhniki" exhibition in 1887, where viewers were presented with a scene whose key message was bringing the idea of kindness and forgiveness to the people. “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her," Christ answered the angered crowd, responding to the question about what to do with a woman taken in adultery: according to the Law of Moses, the woman must be stoned. After which, according to the Gospel, the people, “convicted by their own conscience" (John 8:9), dispersed: Jesus had thus taught a compelling lesson in a new morality.

Polenov's insistence on historically faithful imagery was such that he paid special attention to representing architecture, landscape, objects of material culture and costumes, which were depicted in a realist style. He faced another challenge, too - to bring into equilibrium the colours and lines in all sections of the composition by matching colour spots with one another (brown-red, turquoise-green, golden-white, whose measured alternation makes the depth of linear composition disappear); in handling this he used stylistic formulae close to those of the Art Deco, namely a distinctive flatness or “tapestry-like" quality. It was through such novel stylistic features that Polenov expressed the core idea of the painting - the triumph of truth, beauty and harmony over a furiously angry and unmanageable force.

The painting occasioned much debate, arousing diametrically opposing opinions. It was the young who proved most receptive to the idea and appreciative of the painting's artistic merits. “Some kind of magic opened before me," the painter Yakov Minchenkov wrote in his memoirs, “the singular, captivating colours, the beauteous nature, the heat of the afternoon, the beautiful composition of the temple, the crowd, the adulteress and Christ Himself, interpreted in a novel manner, without the nimbus, wise and handsome in His simplicity. The painting seemed to be all pearly opalescence and fragrance... That precious essence invested in the painting - beauty as the thing most important in art - captivated me and kept me in thrall for a long time."[42]

Vasily POLENOV. On the Sea of Tiberias (Lake of Gennesaret). 1888

Oil on canvas. 79.7 × 159 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

The composition that followed “Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery", “On the Sea of Tiberias (Lake of Gennesaret)" (1888, Tretyakov Gallery), appears to have no narrative at all. The entire desert seems to be permeated with such perfect and eternal beauty, it breathes with such august tranquillity, echoing the profound self-absorption of the traveller who walks engrossed in his thoughts, that viewers had no doubt that they were witnessing something grandiose, despite the absence of a subject in any traditional sense. In “Dreams" (1890s, Russian Museum), Polenov approached the image of Christ in a similar vein. In both paintings the artist conveyed the beauty of the biblical stories through a visible colourful beauty of painted imagery.

“Christ Among the Doctors" (1896, Tretyakov Gallery) is set inside the temple in Jerusalem, the prevailing atmosphere one of deep concentration, which makes itself felt in the semi-darkness of the majestic building, in the beauty of its architectural forms, in the aptly rendered poses of those engaged in conversation, thinking and listening, and in the image of the young Jesus, passionately discussing “the ideal principles of life". Here landscape “enters" the temple's space with streams of sunlight, which break the semi-darkness of the interior, enriching it with colour reflexes.

Vasily POLENOV. Christ Among the Doctors. 1896

Oil on canvas. 150 × 272.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

His work in landscape was for Polenov a natural form of artistic existence and an expression of his ideas about life. Regardless of whatever plans were occupying his mind, no matter what ideas took hold of his imagination, landscape - as a holistic image of the world - was always of paramount importance.

The same is true of Polenov's series “Scenes from the Life of Christ". Beginning the project, the artist wrote about the challenge of creating the image of Christ that he faced: “My undertaking is difficult - unsustainable, but I'm unable to turn it down because I'm too much in thrall to the greatness of this man and the beauty of the narrative about Him... In Gospel legends, Christ is a real, living person, or the son of Man, as He always called Himself, but in the greatness of His soul, the son of God, as others called Him, so what one has to do is to represent in art this living being such as He was in reality."[43] In the painting “On the Sea of Tiberias (Lake of Gennesaret)" Polenov represented Christ in the same manner as in his previous work: the same Oriental face, calm and wise, the same self-absorption, which in this composition is especially expressive since it is informed by the story.

“I love the Gospel tales beyond words," Polenov wrote in 1897, “I love this naive and honest story, love this pure and lofty ethics, love this singular humanity which permeates the entire teaching of Christ."[44] In the late 1890s he decided to set about producing the series “Scenes from the Life of Christ", which would include smaller-sized recreations of his previous Gospel-themed compositions. The practical work on the project began in 1899, after the artist's second journey to the Orient, from which he once again brought back predominantly landscape sketches. Displayed at the 17th “Peredvizhniki" exhibition, the sketches' “freshness" and “compelling colours" produced as strong an impression on viewers as had those from the early 1880s. Now their importance for the series was more obvious: it sometimes seemed as if the artist was deliberately blurring the distinctions between sketch and painting.

The Gospel stories in compositions such as “Dreams" (1890s, Russian Museum), “And Mary Went into the Hill Country" (1900s, Mikhail Vrubel Regional Museum of Fine Arts, Omsk), “He Taught" (1890-1900, Tretyakov Gallery), “Rising Early in the Morning" (private collection), “Were Baptized of Him" (Tretyakov Gallery), “The Woman of Samaria" (private collection), “He Steadfastly Set His Face to Go to Jerusalem" (Samara Regional Arts Museum), “Jesus Returned in the Power of the Spirit into Galilee" and “James and John" (both 1890-1900, Russian Museum) are set amidst a landscape filled with the light of a clear azure sky, with blue hills in the distance and pale blue streams in bright sunlight, against the lush greenery of trees with lilaceous and rosy gleams of the twilight sun. Sometimes the landscapes, such as “Martha Received Him into Her House" (1890-1900, Russian Museum), “The Limits of Tyre" (1911, Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve) feature a magnificent architecture of ideal beauty; in other works, like “He Was There" (1890-1900, Russian Museum) and “Filled with Wisdom" (1890-1900, Tretyakov Gallery) the scene is set in a sunlit courtyard.

In his “Scenes from the Life of Christ" Polenov depicted “the patriarchal golden age" of Galilee, in which the people, immersed in a wondrous world of nature, achieve strength and spiritual balance, wise and free of the vanities of the world. The paramount theme of almost all the pictures in this series is an atmosphere of accord in this land of ideal beauty, a harmony of human relations set amidst a harmony of nature.

Polenov completed his work on the Gospel series, which he regarded as “my opus magnum",[45] in 1908: 58 pieces were displayed in St. Petersburg in February and March of the following year, with 64 later shown in Moscow and other cities. The series proved a huge success, with the “sublime mood" that had possessed the artist during his work passed on to viewers. Polenov's teacher Chistyakov, congratulating the painter on the success of his St. Petersburg show, wrote: “And many artists came with me, and everyone is silent... Even Vladimir Makovsky, for all his cleverness, looked humbled and said, ‘Here Christ's purity is related to the beauty of nature.' How true!"[46] The reactions of viewers to Polenov's new works were unanimous, a rare eventuality in such cases. “His goal," the art critic Yakov Tugenhold wrote in his review in “Moskovskie vedomosti" (Moscow News), “was obviously more philosophical - he dreamed about showing Christ within nature, engaging nature to participate in His great life. As a result, the very personality of Christ seems to be dissolving into the landscape, receding into the background. in Polenov's pictures Christ is felt through nature, through the grandiosity of Capernaum, in the serene grace of ‘sown fields', which, strangely enough, have about them a certain air of humility characteristic of that Russian nature which ‘the Lord walked all over, blessing'."[47] The critic's opinion about Polenov was echoed in by Feodor Chaliapin in his autobiography “Pages from My Life": “This outstanding Russian has somehow managed to share himself between the Russian lake with its lily and the harsh hills of Jerusalem, the hot sands of the Asian desert. His biblical scenes, his high priests, his Christ - how could he combine in his soul this poignant and colourful greatness with the quietness of a plain Russian lake with its carp? Could it be because the divine spirit soars over his serene lakes too?"[48]

Polenov was working at the same time on “Jesus from Galilee" - a compendium of the four canonical Gospels - and a literary and academic text, a commentary to his painting “Christ Among the Doctors". As he worked on his Gospel images, the artist was also composing music all the time. He created an All-Night Vigil and a Liturgy, compositions in which, as he himself said, “working on the visual and verbal imagery of the Gospels, I tried to convey my emotions in sound, too."[49] In a reciprocal manner, tender, at times sublimely solemn, spiritual melodies can be clearly heard in the visual elements of the series.

Many Symbolist artists at different stages in the evolution of the romantic-symbolist worldview felt compelled to use verbal or musical creativity to achieve a more expansive and profound visual imagery - to express the inner recesses of their souls and dreams, the polyphony of their emotions and their subtlest impressions. It is characteristic that Polenov used these related forms of creative activity to produce imagery for the Gospel tales that so enthralled him, that he loved “beyond words".

Landscapes of the 1890s-1910s

By the early 1880s Polenov was already producing not only intimate and lyrical landscape scenes but also revealing a penchant for epic landscape imagery. The northern scenery of the Olonets Governorate, where his parents' Imochentsy estate was located, was the prime location to provide sources of creative inspiration for his works in this vein. According to Polenov himself, writing in a letter to Savva Mamontov on May 22 1914, his reminiscences about the summers that he had spent there were very dear to him: “It was on the spell-binding banks [of the River Oyat - E.P.] that I found an immense store of artistic, physical and spiritual energy. I am still making use of the visual resources that I found there."[50] In fact, Polenov created such paintings highlighting the distinctness of the region's northern scenery both in the 1880s and, after the Imochentsy estate was sold in 1884 for family reasons, over the two decades that followed.

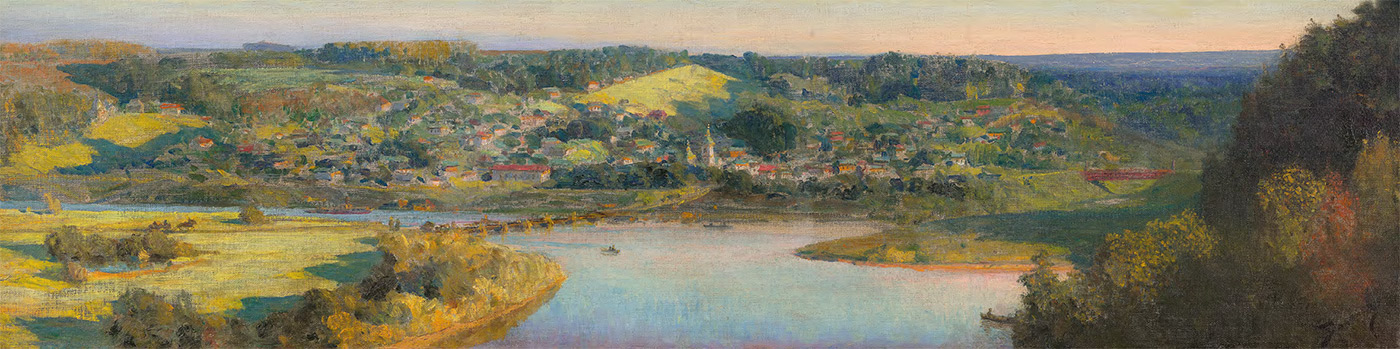

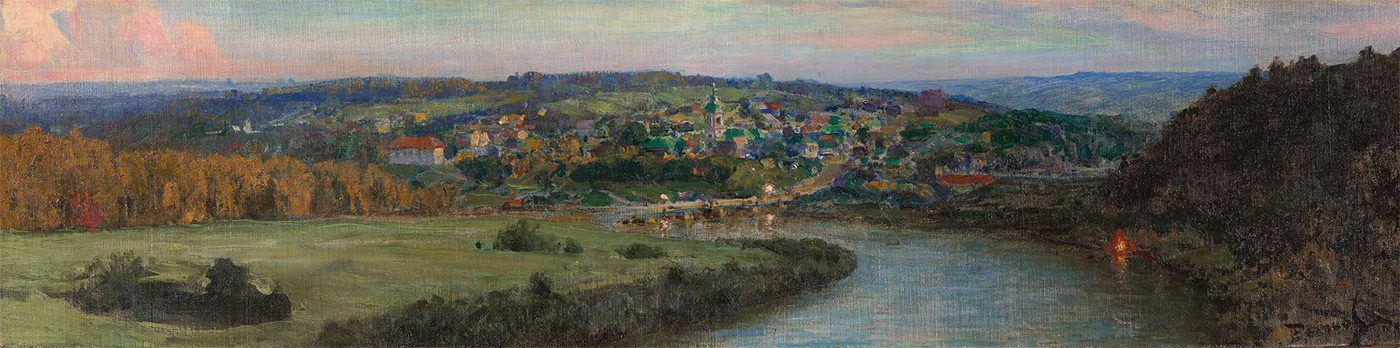

From the sketches that he had created in 1880 on the Oyat, Polenov would produce several paintings, including “The Oyat River" (1886, recreated in 1915, both versions at Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve). The artist would continue to look for landscapes with such wide, spreading spaces in the 1880s in both Abramtsevo and at Zhukovka on the River Klyazma. Such works feature the main elements of Polenov's signature Russian landscape imagery: a river flowing with measured majesty along its banks - hilly, meandering or wooded, with sections of backwater, small meadows and expanses of land stretching away to the horizon. Polenov received just such a real opportunity to paint this type of scenery in 1890 when he settled on the Borok estate by the Oka river, as seen in “A View of the Oka from Old Byokhovo" (1891, Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve). It was there that Polenov's distinctive landscape imagery, combining lyrical and epic features, would emerge.

The artist took a while to engage with this new form of landscape imagery, related as it was to the expansive riverside views of the Oka. In Byokhovo, in 1890, he completed the landscape “Autumn in Abramtsevo" (1890, Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve). Based on the intimate small sketches of Abramtsevo that he had made in the 1880s, such as “The Vorya River," “A Boat on the Vorya at Abramtsevo" (both 1880, Abramtsevo Museum-Reserve) and “The Vorya River. Abramtsevo" (1880s, Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve), this painting, with its neat decorative and rhythmic structure, carefully calculated consistency of both the composition as a whole and its individual details, and a diversity of colour scheme that absorbed the full wealth of the autumnal colours of nature, would become the fullest expression of the artist's love for this time of the year. “Autumn in Abramtsevo" is a solemn polyphony with complex rhythmical turns of melody that transform into chords of colour on the artist's palette. Interweaving and growing in their emotional intensity, these chords form what might be called counterpoint, reminding us of the artist's gift for music and his experience as a composer. “I love music passionately," Polenov would write in his notes toward an autobiography, “perhaps even more than painting. Along with the great moments of happiness which painting has given me, I have to say frankly that I have lived through whole years of bitter disappointment, even agony [with it]. But music has brought me only joy and consolation."[51]

Vasily POLENOV. Autumn in Abramtsevo. 1890

Oil on canvas. 77.5 × 126 cm

© Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve

“Autumn in Abramtsevo" is filled with a sense of drama and a feeling of acceptance of sorrow and bereavement, of the “deliverance" from suffering through the beauty and harmony of the world that Polenov had depicted so vividly in “The Patient". After the death of Polenov's son, his first child, at the age of two, the grieving artist would often come to his favourite nook in the park at Abramtsevo on the banks of the Vorya, which he had previously depicted in the sketch “The Vorya River" (1880). As its title suggests, the sadness of autumnal nature echoed his feelings at the time. But the mood dominating the landscape overall is different. The sad melody of the picture's central section is balanced with the cheerfully resounding golden-orange birches and the bright greenery of the trees on its edges, their colour design bringing closure to the deep sense of sorrow conveyed in the painting's middle part.

Another work, “Golden Autumn" (1893, Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve), is full of musical associations as well. In his memoirs, Yakov Minchenkov describes how he once came to Polenov's house but decided not to enter, in order not to cause a distraction from the music that he was playing. “In a broad spectrum of chords," Minchenkov wrote, “he was playing some chorale, written in a major key. Sometimes a bass part didn't come out well, so Polenov would start again, bringing order to the counterpoint, and solemn and luminous sounds would ring out, then quietly fade. There was a feeling of imperturbable calm, adorable contemplation of the world. It became dark, the music died away, and I knocked on the door... - ‘No, never mind, I was just passing by,' I said. If I could only learn to compose music like Bach, so dispassionately and so sublimely, with such abstraction, removed from the trivialities of everyday life. How tired I am of this prose, though it is not a rare case that it is extolled in art."[52] It is exactly such “sublime" music that resounds in Polenov's “Golden Autumn", with its wonderfully clear colours of early autumn, and in the line of its horizon, traced so softly that it is difficult to know whether the sky is a continuation of the earth or the earth is a continuation of the sky. The boundlessness of the world, where this beautiful and so comfortably “lived-in" earth with its little church provides the point of reference - this is the foundation of the contemplative mood inspired by the landscape, which recreates the unity of things both human and cosmic as the fullest picture of the world.

Another autumnal landscape brings us to the location of the old Trinity Church in Byokhovo, depicted in “Golden Autumn". In 1906, Polenov built a new church dedicated to the Holy Trinity next to the old one, which had by then grown dilapidated. In 1911, in a letter from Borok to his young friend Leonid Kandaurov, Polenov wrote about his thoughts as he contemplated the construction of the church: “Throughout history aesthetics has been one of the most loyal and powerful attributes of religion. Most great edifices grew from religion, they came into life thanks to religion, and the church dedicated to the Divinity, becoming a house of prayer, became also a keeper of art, or of the arts. Our Church, which recognizes painting, music, poetry, is already the Temple of Art as much as it is the House of Prayer, and in this lies its great power and importance for the past, for the present, and for the future... These are the thoughts that led me to build a temple of prayer and art for our peasant neighbours."53 The Holy Trinity Church, built in the village of Byokhovo to Polenov's design and, for most part, thanks to his material support, became not only both a “House of Prayer" and a “Temple of Art", as it creator envisioned, but also what might be called a tribute to the artist himself.

In 1907 Polenov painted “The Church at Byokhovo" (1907, private collection), the painting featuring both Byokhovo churches - the old wooden Trinity Church built in 1799 and, next to it, the new Holy Trinity Church, or the Life-Giving Trinity Church, built to his own design. The historical moment when both churches stood side by side was captured by the artist. Felicitously placed on a high hill amidst the Oka's riverside expanses, the two churches - the old one, crumbling, and the new building, with its lucidity and neatly organized complex design, with the peculiar picturesqueness of its shapes - produce an especially strong and well-balanced impression, set as they are against the blue of the sky, the river, and the woodlands that stretch far into the distance, amidst the golden autumnal ornamentation of the earth.

Polenov's works of the 1890s-1910s are distinguished by the special attention that the artist paid to nature's different states, as is clear from the titles of the works that Polenov gave them when he exhibited them at the Moscow Society of Artists shows from 1893 onwards through the 1900s - “So Hot", “Impending Storm", “Getting Cold", “Snow at Sunset", “Snow Melting", “Bad Weather", as well as “Grey Autumnal Day" (1909, Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve) and “Frosty Day" (1910s, private collection). “Early Snow" (1891, Tretyakov Gallery) is especially worthy of attention, the composition compellingly demonstrating the artist's sensitivity to the life of nature and his eagerness to capture its barely noticeable changes at critical moments of life.

When Polenov settled by the Oka river, he was able to fully commit himself to his favourite pastime - creating a fleet of boats. They were built right there on the estate, to the artist's technical drawings and pictures, and kept through the winter at the “Admiralty", a small house on the estate (“The Admiralty", 1900s, Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve). Polenov often depicted boats and barges on the river at this time, in works such as “On the Oka. Mityukha" (1896), “Barges on the Oka" (1897, watercolour), “A Red Sail" (1911, all at the Vasily Polenov Museum-Reserve), “A Summer Day" (1903, private collection) and “A Backwater on the Oka" (1906, private collection).

Vasily POLENOV. A View of Tarusa. 1910s

Oil on canvas. 42 × 141 cm

Private collection, Moscow