Remembrance of the Future

“SOME SPROUTS DO NOT BLOSSOM,

SOME BLOSSOMS BEAR NO FRUIT”

CONFUCIUS

The 1st International Beijing Art Biennale was an audacious debut worthy of competition with such famous international cultural events as the Biennale di Venezia, the Kassel documenta, the FIAC contemporary art fair in Paris, and the Chicago International Exposition of Contemporary and Modern Art. It was the first time that such a large-scale, long-term cultural initiative to create a new international forum of contemporary art had been attempted in Asia.

In order to make the event meaningful and representative some world-famous artists were invited to participate. Among them were France’s Arman, America’s Robert Rauschenberg, Spain’s Antoni Tapies, Germany’s Georg Bazelitz, and some other no less renowned artists selected by the Italian curator Vincenzo Sanfo. These names were to act as a kind of a magnet, attracting artists from 49 countries, from Asia and Europe, America, Africa and Australia, who showed more than 400 works of art: paintings, drawings, sculptures, and multimedia projects.

The theme of the Beijing Biennale, as stated in the preface to its excellent catalogue, was “Originality: Contemporary and Local”, which, according to the organizers, corresponds to the Confucian interpretation of aesthetics - “both perfectly beautiful and absolutely innocent”.

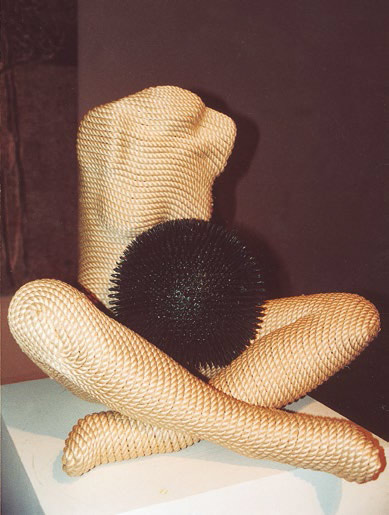

One managed to see that, alongside some Socialist Realist and Pop art kitsch, there were some really original, distinctive and unexpected works - vivid evidence of the dynamic evolution of Chinese contemporary art over recent years. This was an encouraging development in itself. There were real discoveries; one of them, “Bathing Children”, a multi-figure composition by the young sculptor Chen Wenling, simultaneously recalled the bathing boys of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin and the celluloid toys of the 1950s. This plastic installation was somewhat reminiscent of the silicone sculptures of Australia’s Patricia Piccinini showcased at the Venice Biennale. This kind of symbiosis is a common enough phenomenon in contemporary art and culture; it reveals some obvious manifestations of the crisis that traditional forms and means of visual arts are experiencing, as well as the quest for an artistic metalanguage that would reflect the spiritual and aesthetic values of today.

As for Chen Wenling, it is worth noting that his work “Red Memory” goes beyond what is purely national and is marked by an indirect association with scientific discoveries, genetic engineering and advanced technologies that are universal, rather than national in nature. The viewer should also bear in mind that his multi-figure installation will be perceived differently depending on its location, whether real or virtual, and on the space that it would occupy in our imaginations. For this writer, the work became the most striking discovery of the Beijing Biennale.

The international section of the Beijing Biennale was hosted by the Fine Arts Museum in the monumental Chinese Millennium complex. My first impression of the international section was a bit disappointing: next to some first-class works of art were others that seemed arbitrary and of questionable professionalism. This might be explained by the fact that certain countries were represented poorly, by secondary and amateurish works. I do not think it had anything to do with the organizers, who welcomed all foreign participants with proper respect. I believe that the key here lay in the level of competence and responsibility of the organizations and individuals in charge of choosing the works for their country’s collections. The bar was indeed set high, by such artists as Arman with his “Discus Thrower”, Costas Varotsos with “Horizon”, Antoni Tapies with his “Background of Grey-Rose”, Robert Rauschenberg with his “Page 12, Paragraph 7” and, of course, Qi Baishi, with his iconic works representing Chinese classical art.

Unfortunately, this part of the exhibition turned out rather uneven, “wobbly”; the works of the artists selected by Vincenzo Sanfo dated back some 10 to 15 years and were not the highest achievements of such masters as Adolf Penck and Georg Baselitz (both from Germany), to say nothing of the mediocre works by the Columbian artist Ana Mercedes Hoyos and the Italian Omar Galliani.

The same should be said about the participants from the former Soviet Union (Armenia, Latvia, Belarus), whose works appeared bleak and hollow, and only the Lithuanian exhibition proved a pleasant exception.

Norway, although represented solely by the internationally recognized artist Grete Marstein, who frequently shows her work at international events and exhibitions, produced a tired and feeble effect. Iceland, too, with Pjetur Stefansson’s eclectic Pop art work, left us baffled.

Other soaring “heights”, as represented by the works of Swedish artists, were not marked by any particular originality, but were really highly professional; the same is true about the participating Danish artists, namely Erik A. Frandsen, Bj0rn Nergaard, Torben Heron and Lars Nergard.

At first, the Australian part seemed impressive and well-rounded, but in essence, it was purely decorative design. As for the German, Austrian and Italian sections, they were as dull as that of Hungary. One cannot find any reasonable explanation for such an uneven level of the works that were shown at the Biennale; it is hard to understand why even the leaders of contemporary Western art were so poorly represented.

Only three Russian artists were invited to the exhibition - Tair Salakhov, Vyacheslav Mikhailov and Yury Kalyuta: again, such a choice seemed to have no reason behind it at all. However, the very modest - both from the point of view of the number of participating artists, and the quantity of the works exhibited - Russian section did not fail to attract the attention of the public, due to its highly professional, emotional and philosophical message, first and foremost due to Salakhov’s paintings, marked by his unique style, vivid images and inherent artistic value. Kalyuta, who received the Biennale award, exhibited three paintings, rather different in the manner of visual-plastic decision; together with the works of Mikhailov, they were seen as typical examples of the contemporary Petersburg school of art, especially since there was nothing else with which they could be compared.

The same was characteristic of other countries’ sections: too few works of art to reach any conclusion on the trends, movements, peculiarities and tendencies that shape contemporary national-local art - even though quantity never automatically means quality, particularly in art. A real work of art is unique, and there is no place for summing up - one should not judge, or be persuaded by the number of works.

Thus it was impossible to conceive what the situation in contemporary British art is from the works by the two artists, the sculptor Michael Lyons (“Starfish: A Sailor’s Dream”) and the painter Yvonne Hindle (“Full Spectrum Current”), whose works, although attracting public attention, provided no sense of discovery. The painted iron constructions of Sebastian Enrique Carbajal or the surrealistic painting “The Angels of Conscience” by Rafael Cauduro did not shed much light on the state of contemporary Mexican art, either. No national Islamic identity marked the paintings of Tunisian artist Gouider Triki, whose works echoed the fantasies of Marc Chagall. The same referred to the Turkish artists Selim Birsel and Murat Sahinler, the Serbian and Montenegrin artists, and to the Pakistani sculptor Amin Gulgee.

Very often a certain peripheral understanding of the innovatory limited the national in a scarce introduction of ethnographical elements, and the Vietnamese and Indian exhibitions were good examples of that. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to state that the Biennale did not represent unique national artistic achievements, whether traditional or essentially innovative. Some exceptions were the large lacquer panels by the two Vietnamese artists, “Remnants of Time” of Trinh Quoc Chien and “The Light of the Spirit” of Mai Dac Linh.

The 1st Beijing Biennale organizers made the decision to include a national exhibition of Chinese contemporary art (which is only understandable and perfectly justified) as well as one of modern Korean work, supplemented by two solo retrospectives: of Qi Baishi, the classic of traditional Chinese painting, and Tatsuo Takayama, the renowned master of Japanese art.

In order to correct the obvious imbalance in favour of Asian participants, it was decided to show as a part of the international exhibition a number of works of art from the French Autumn Salon, thus celebrating the centenary of the Paris Salons. It was really a valuable and well conceived addition to the works by Spanish, Italian, Irish, German, French, Columbian, Argentine and American artists.

It might seem that such an exhibition concept should correspond to its formulated aims, but practically speaking, some country’s exhibitions ended up inferior and occasionally, as we have mentioned above, accidental and ambiguous.

The 1st Beijing Biennale encountered the same problems as other long-standing international art forums like the Biennale di Venezia, the FIAC contemporary art fair in Paris, Kassel’s documenta and others. The reality is that the majority of world-famous artists do not belong to any artistic unions, and deal instead with certain galleries and dealers. Sometimes the situation is rather similar with younger artists who do not yet belong to any unions either, and find themselves on the side at the major international events. This is a widespread problem; however, it appears to be a useful tool for those who manipulate and control the art market and art’s future with it, but that is a different story altogether.

To return to the 1st Beijing Biennale and the way it reflected the general state of contemporary art, I should note that it was the Chinese exhibition that became the real discovery, with the exception of its large- scale outdoor sculpture part.

If I was disappointed with the international part of the Biennale - it seemed full of eclectic, depressing replicas of things past - the Chinese part really encouraged me: contemporary Chinese art seems to be in a constant process of search for a new artistic language to correspond with the epoch of globalization, as well as trying to overcome the dictatorship of technocratic economic and political interests. China presented a wide range of works - from the classical, in the tradition of guohua, to Socialist Realism at its most expressive and conceptual alternatives in the framework of known tendencies of Western post-modernism, to the trans-avant-garde - a direct result of globalization.

Among the most brilliant examples was Zhang Lichen with his China ink and watercolour piece “The Charmed Lotus”,depicting a poetic landscape in a laconic and discerning style through the skilfull use of texture and space of the paper. A worthy follower of the tradition of Qi Baishi, he nevertheless creates truly contemporary art. I was impressed by the fine and delicate oil panels in the Go Hua style by Hu Yaqiang (the series “The Garden of One Hundred Grasses. 5 Autumn Songs”). Xu Lele followed and developed the rich traditions of Chinese genre painting. His watercolour work is full of a generous irony, numerous historical details, and a tenderness in depicting subjects. These works attract the attention of the viewer with their really pure colour intonations, the musical rhythm of composition and a creative attitude to national heritage.

Quite a number of paintings by prominent Chinese artists (Wang Hongjian, Tao Shihu, Zheng Yi) demonstrated their commitment to the traditions of Socialist Realism, professionalism and social relevance. Five imposing portraits, united into one composition “Brothers and Sisters”, painted by Zhang Chenchu vividly connected with American hyper-realism, though with no traces of any direct mechanical application of its algorithms. The watercolour “Memorial Years”, by Liao Jianhua, was in the same hyper-realistic style.

Shen Ling’s painting “Making Eyes” reminded viewers that the traditions of Fauvism and Expressionism are still alive. The subject of Ling,s canvas might have been painted under the influence of the cruel realism of Britain’s Francis Bacon. However, the abstract paintings of Li Lei (“Birth”)and Qi Haiping (“Black Theme #25”) were expressive but far from original.

The most striking - for its social context and technically skilfull implementation alike - was Leng Jun’s painting which visualized an upside-down mattress frame with a dirty, ripped-out cloth, used syringes and old medical instruments. The frame is easily taken for prison bars, aggravating its gloomy atmosphere to an extreme. Full of real dramatic tension, this painting is a warning against temptations and illusions, and appeals to reason, mind and sympathy simultaneously.

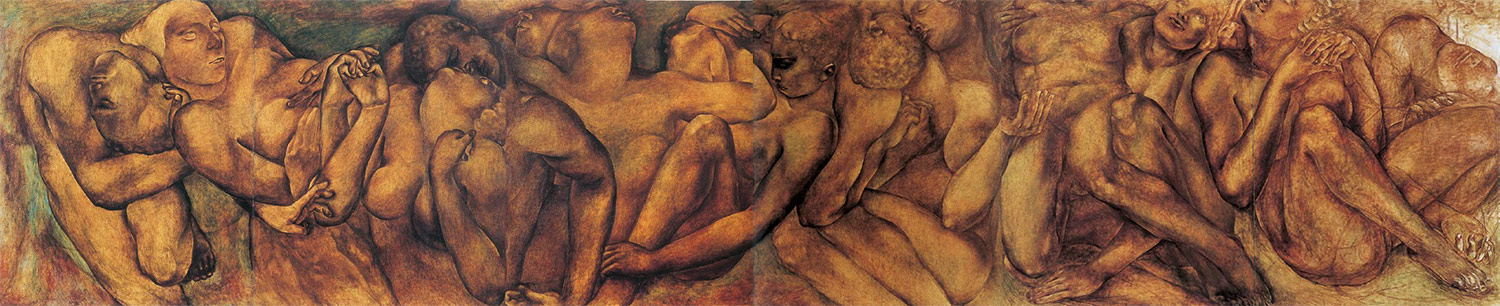

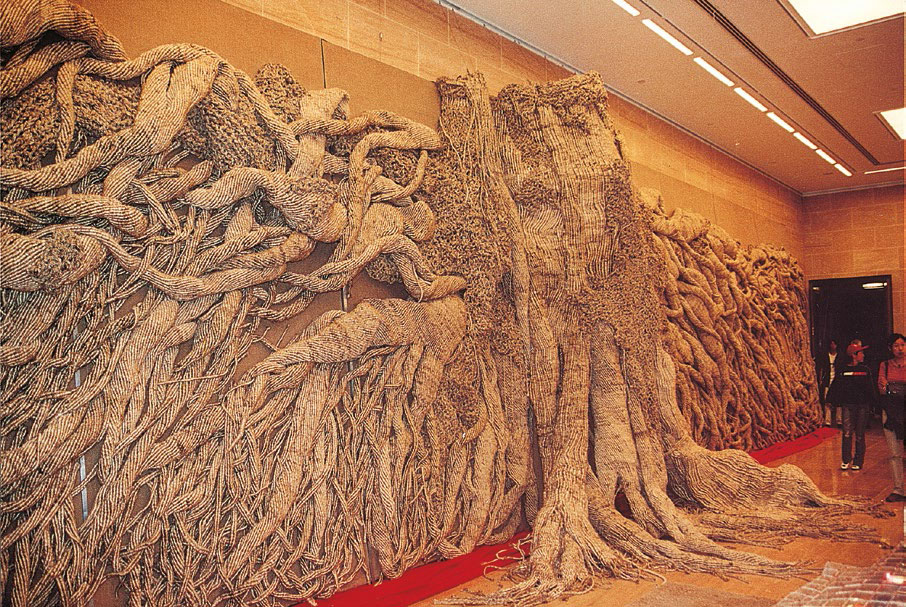

The other work whose scale and craftsmanship attracted attention was - a very rare (or perhaps just little known) case in contemporary artistic practice - a collective creation made under the supervision and guidance of Guo Zhenyu. It presented a giant sculpture relief composition with a very fitting title, “Chinese Roots”. No less impressive was the sculptural portraiture of “The Spirit of the Great Wall” by Shi Cun, and a curious installation by Ren Guanghui entitled “The Time of Chinese Ink Watering”. It is also worth mentioning a copper and steel object-bust installation by Wang Zhong titled “Relics of Contemporary Culture”, with its peculiar mixture of Asian and European symbolism.

I should say that this combination, mixture and conjunction of the East and the West - with an equal measure of achievements and fiascos - seemed to characterize the Chinese exhibition. Thus, the kinetic mobile-like objects of Fu Zhongwang - though different in size and content - might be read as a paraphrase of the work “Cell” by the Finnish artist Jaakko Niemela. An interesting composition of granite rings “New Ideas” by Li Rihuang matched a wooden sculpture, “Structure”, by Lithuania’s Vaclovas Krutinis. Some of the Chinese artists could not “escape” the influential impact of George Segal, even though they transformed his Pop art-inspired conceptualism into naturalistic shapes of painted papier-mache figures.

Also distinctive were “The Oracle” by Canada’s James Mac - an original sculpture made of cardboard, ropes, nails and various other everyday materials; and the small pieces by the Iranian Fatemeh Emdadian (a prize-winner at the Biennale).

There is more to be added about the Chinese part. I should say that Chinese artists very often apply hyperbole as a form of self-expression; only natural for their Eastern philosophy, it still manifests itself differently from in the Western tradition. In the lines of an ancient Japanese poem: “The quiet light of the Moon, /A drop of rain on the motionless branch of the tree...” Universal minimalism, attention to the very smallest detail, to a blade of grass, a moth, seeing poetry in the everyday and each passing moment, reveal one of the distinct peculiarities of the Culture of the East, one which I managed to see and appreciate in the works of the Chinese artists.

Participants in the Biennale symposium discussed issues of national creative identity, authenticity, originality, and the importance of art; however, the subjects were too general to encourage real conversation. Nevertheless, some speakers offered informative and almost controversial presentations.

As the process of globalization is wiping out the national and the original, it is very difficult to judge exactly what is what in the contemporary art movement; besides, perception of art is often highly personal, even contradictory. In a letter addressed to Abbot Pierre Desfontaines, the French translator of “Gulliver’s Travels”, Jonathan Swift wrote that different peoples had different tastes, which did not always coincide. But good taste - he went on - is good taste everywhere. Genius that he is, Swift managed to give a definite answer to the general question bothering all those professionally interested in the trends of development of contemporary art.

To conclude: let us return to Arman and his brilliant example of good taste in art, his “Discus Thrower”, which received the First Prize of the Biennale. Arman’s avant-garde remake of the ancient Greek sculpture turned out to become an absolutely original, perfect work of contemporary art. This sculpture is also a fitting illustration of Swift’s ideas: Arman exercised his unique imagination and creativity to “dissect” Myron’s 5th century B.C. classical masterpiece and create new meaning and aesthetics.

The “Discus Thrower” of the virtuoso French master of the grotesque and paradox is, and will remain a special symbol of the unseen spiral which determines the development of art; at the same time, it is a wondrous work of art, a benchmark of artistic craftsman-ship, impeccable taste and style. This is exactly why we choose to conclude this short review of the 1st Beijing Biennale with Arman’s creation, one that symbolizes the connection between the past, present and future.

The Beijing Biennale has proven that it is a viable endeavour, a launch pad for Chinese artists who aspire to be a part of the world contemporary art scene. The most gifted of them have already been successfully competing in the world art market and claimed their rightful place among the most distinguished artists of our time.

Plastic. Detail

Iron, glass

Mixed media

Mixed media

Oil on canvas

Bronze

Oil on canvas

Copper, waste wood

Wire netting, electric motor, halogen light

Stuffed hare, mirror, candle

Stainless steel, copper, steel wire

Watercolour on paper

Oil on canvas

Bronze, stone

Wood

Granite

Enamel on aluminum, photo

Oil on canvas

Wood-block print

Oil on canvas

Ink and wash, colour on paper

Fibre, branch, wood, plastic

Mixed media