Natalya Nesterova. PORTRAIT OF AN ARTIST

Let the game begin. Have these hollow cocoon-bodied figures really reached us from some metaphysical remoteness, or does it just seem that way? Their figures are wrapped with bandages of playing cards, like the wounded or the mummified dead of Ancient Egypt. They are speechless, they have nothing to say, yet we understand that they are arrivals from unknown lands in which passion burns souls to ashes, which is to say that they are allegories in the most banal and most elevated sense with regard to style and the meaning of the figure. We also know that it was the artist herself - Natalya Nesterova - who invited them: it is at her canvases that we are looking, those are her colours and her images. On a table in her studio on Arbat Street there is a partial deck of cards, a game of solitaire spread out nearby. Let the cards foretell.

Valery Turchin

From the article “Cards, Symbols, Art” published in the “Nashe Nasledie” magazine (#59-60, 2001)

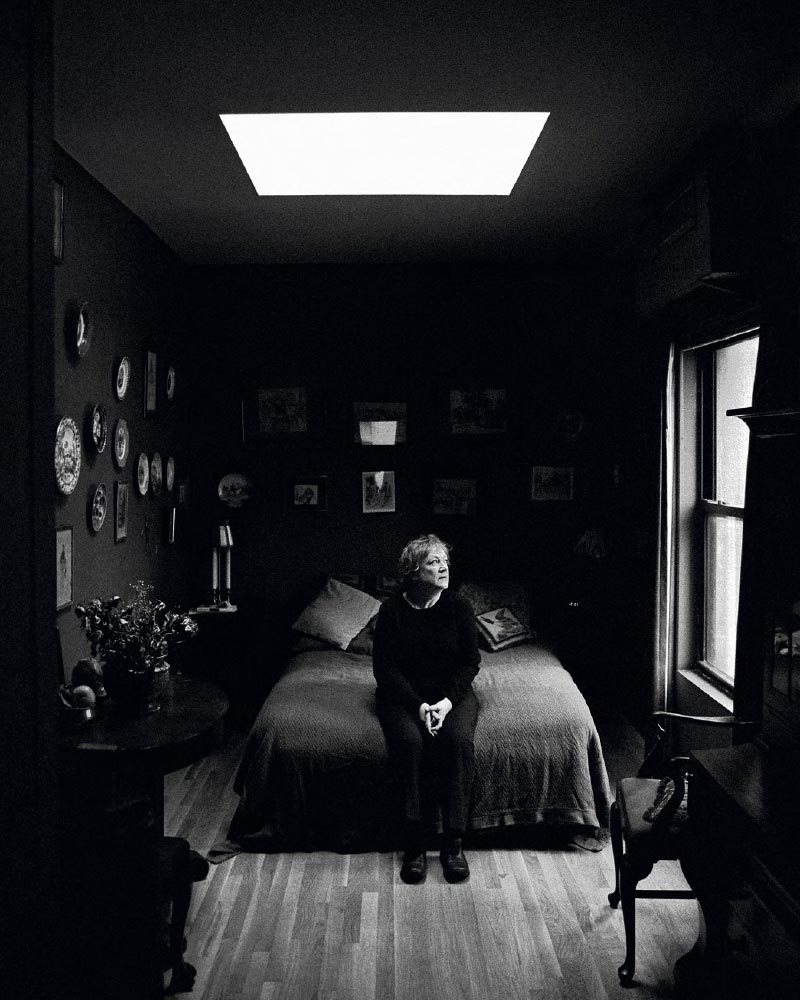

Natalya Nesterova. Moscow. 2000s

Photograph by Yuri Rost

Natalya Nesterova

Alexander Morozov*

* Originally published in the “Tretyakov Gallery Magazine” in the article titled “On the Cross-roads of Mastership. Three Exhibitions in the Tretyakov Gallery” (#2, 2005).

The compelling and deep-seated need for active engagement with the public streams through the veins of today’s art. A new expressiveness of visual form distinguishes the art of Natalya Nesterova, one of the leading painters of the “’70s generation”, who is clearly not content to rest on her laurels with passing time.

So what has changed? Three things perhaps. The first is related to the nature of the motifs favoured by the artist. Whereas, previously, Nesterova had usually been attracted to copious detail in unassuming scenes from everyday life, this focus seems to be shifting to the depiction of certain rituals of life vested with symbolic significance and not bound to a particular historical period. Contemplative views of nature, meditations by the seas or in a park are complemented with various episodes of play. It is not surprising that, in the series of momentous scenes from the perennial drama of human existence, we now find New Testament narratives. Along with these images, there are images of feasting on the gifts of the earth and sea in superb “restaurant-themed” still-lifes. And, on the other hand, there are many compositions with birds intruding into human space.

Natalya NESTEROVA. Oysters. 1985

Oil on canvas. 100 × 100 cm

We observe the metamorphosis of the theme of nature in Nesterova’s art. Admirers of her earlier works used to value the balance of natural and human elements. That was a contrast between two forms of existence: one impeccable (and beautiful: the natural setting that surrounds humanity) and the other very far from ideal, not yet grown to its greatest potential capabilities, not yet entirely fulfilled (the human being “here and now”). Nature’s vital potential in Nesterova’s compositions is now often associated with bird imagery: nature is like a seagull, who can sometimes act quite aggressively as it participates in the universal drama of competition for survival. The viewer would be right to point to this as a new aspect in the philosophy of nature in Nesterova’ art.

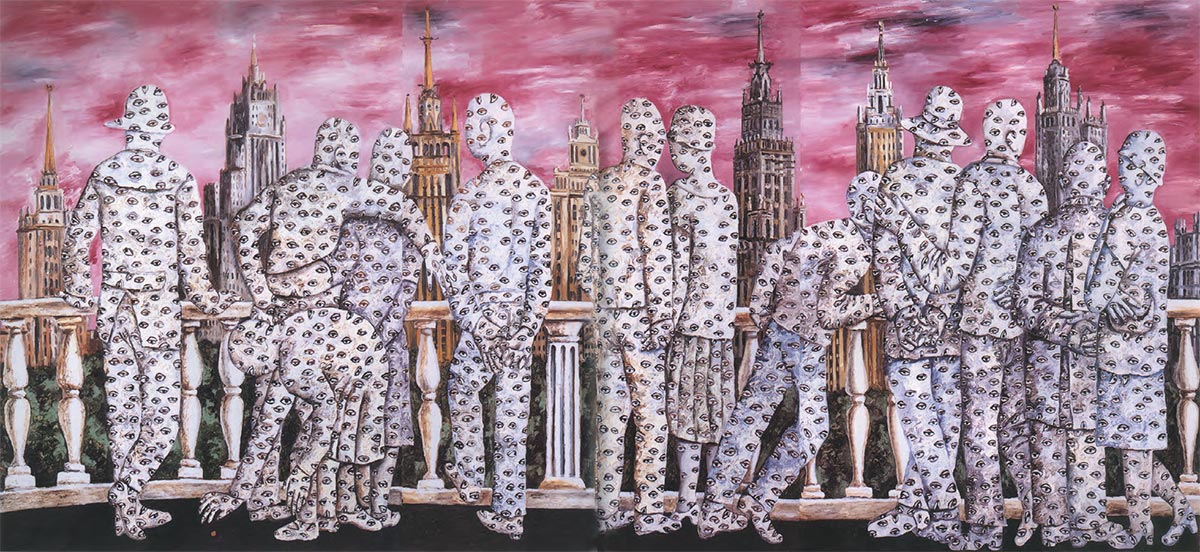

Her present-day understanding of the picture as a whole becomes dominated by the philosophical element; her paintings are often similar to parables. The artist unequivocally presents some of her works as a study into different life statuses and psychological types of human being. Take, for instance, her 2003 series: compositions such as “Independent, bold, obedient”, “Restless, aggressive, conceited”, “Insouciance, hope, despair”, or “Youth, maturity, old age”. Visualising all these concepts, the artist refers to humanity’s archetypal, timeless, “biblical” core. The viewer sees silhouettes of naked figures filled in with the archaic script of Hebrew words. As a result, such pictures resemble either prehistoric petroglyphs or the primitivist formulas of the pioneers of the Russian avant-garde. A human riddle, “a figure made of words”, can be featured in Nesterova’s pieces beside “a figure made of eyes”: her paintings feature equally abstract human silhouettes that, scribbled over with primitive images of an open eye, stare at Moscow, leaning against the balustrade of the famous observation platform atop the Sparrow Hills. Furthermore, this intellectual esoterica paradoxically transforms into a keenly experienced, all-consuming, nearly animalistic curiosity, a state that is usually described as being “all ears” (or all eyes).

Natalya NESTEROVA. Moscow. 1989

Triptych. Oil on canvas. 170 × 420 cm

Tretyakov Gallery

At the same time, Nesterova modifies the arrangements of her “picture framing”. As if trying to accommodate the demands of the conceptual terseness and didactic lucidity of presentation typical of parables, she narrows her range of vision in relation to detail, to fragments of what’s depicted, squeezes the frame of her composition, shifts from “long shots” to “middle distance”. Now, for instance, she no longer leaves vacant space for a free flow of landscape imagery in the background - instead, she strives to achieve a rigid balance between all elements of the composition, giving each only as much space as is needed “for the performance to go on”. This makes the pictorial structure of Nesterova’s compositions more compact. Such self-restraint in the selection of objects on which to focus the artist’s and the viewer’s attention could produce an excessively dry style if the artist were not compensating for it in some way. And here it is important to point out the third important characteristic of Nesterova’s recent artwork. Let’s put it this way: she has made a step forward in her treatment of paints.

The artist was always fond of oils, of the paint itself, its mass, relief, texture and surface. She had always been keen on layering paint in order to mould the noses and hairstyles of her female figures, or rocky mountains, or the petals of flowers arranged in large tangible clusters. Next to these elements, there could be sky, water or even the wall of a pavilion in a park, crafted lucidly and finely. Now, Nesterova prefers homogeneous pictorial textures, spread all over the canvas with rhythmic, steady movements of the brush. Nesterova’s techniques are akin to those used by Pyotr Miturich during his late period, with the same energetic, pulsating brushwork that advances in sync with the artist’s inner rhythms. What the artist applies to the canvas is not a pure pigment but colour - the colour that the artist needs pursuant to the logic of her visual themes. Here, we can see an evolution of the methods of the Russian Cezannists - the artists of the “Jack of Diamonds” group - which cystallised in their mature art. As Nesterova strengthens the forceful, rhythmic element of her brushwork, she achieves a special energetic intensity of pictorial expressiveness.

In this regard, some commentators point to the frantic colourfulness of her new paintings. Indeed, these images are distinguished by an astonishing variety of colours. But, most importantly, viewers behold not just colours, they behold colours in the tangible body of the brushwork through which the artist achieves homogeneity in the modelling of visual space - the imagery that is not so much crudely raised as virtually three-dimensional. Extraordinarily beautiful and dynamic, this visual idiom is charged with an intensely vibrant visual experience that affects viewers just as strongly as, say, the “physical interventions into life” committed by Nazarenko. In Nesterova’s sagacious restraint, in the original expressiveness of the two “Amazons” of the 1970s - so close to and so different from each other - we behold the wide range of achievements, explorations and enticements of modern Russian painting, which, as “cutting-edge” critics would have us believe, died long ago.

The Memories I Keep

Natalya Nesterova

The War had not yet ended. The year was 1944. I was born. For me, my childhood was the most wonderful time, the “dreamtime” of my life. My parents, Igor and Zoya, my maternal grandparents, Nikolai and Anna, and my paternal grandparents, Igor and Zoya, were all overjoyed by this frightful little child - gaunt and wailing, but doted upon. That’s probably why, despite all the misfortunes that were to follow - the loss of loved ones, the bitterness of a hard life - I was protected from real life. Mama and Papa, both architects, were busy with their work; they were both studying at the Architectural Institute, which is what had brought them together, and so I was left to my grandfather and grandmother. My grandmother, Anna, was a strict, unbelievably talented teacher (of Russian). There was never any feeling of compulsion during my childhood - I started to read and write early, and I could draw even earlier. The walls of our home were all hung with Grandad’s paintings, so that, from the moment I opened my eyes, I found myself in a wonderful environment of beautiful landscapes and still-lifes that remain constantly before my eyes. Sergei Barkhin, who invited us to work in the Russian Institute of Theatre Arts (GITIS)[1], always said that one needed to enter a painting, to walk around in it, to ponder it, to admire it, and, on leaving it, never to let it out of one’s heart. My grandad, Nikolai, instilled me with life. He used to play with me, sitting me down on an armchair transformed into a carriage, with a stool and felt the boot in front functioning as a horse’s head, and we would head off on amazing adventures. Granny would sleep on the couch - little children (in the singular) were not her passion. She did, however, teach me to read and write and, in doing so, revealed to me the whole of Russian literature and, later, when I was sitting with Mama in the park or went to the river to draw something, Mama would read me Dickens, and I would cry my heart out in secret, which, by the way, I still do today - cry bitter tears over books, music and paintings.

In 1951, I entered MSKhSh[2], a school not far from our home, and, in the same year, my grandad Nikolai died, causing an unbearable sense of loss that has stayed with me all my life. I would like to think that he can see how hard I try to do him proud; maybe he can indeed see it.

When I entered first class (this was in 1955), I met my friend Tanya Nazarenko, with whom I have been quarrelling and making up for 66 years now, offering mutual support always, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

I think that art schools (I don’t know about the modern ones) teach children to work, to look around themselves, without putting them off their possible profession. There were not so many of us then (born in those difficult years), and we were a cheerful lot, gorging ourselves on the good books and wonderful paintings that started to become accessible to us from their closed repositories, saved by Vasily Pushkaryov and many, many wonderful people who preserved, and more importantly, loved art.

In 1962, part of our class moved on to the Surikov Institute[3]. The boys of our class were taken away to our gallant army for three years, so we wrote them letters and lamented their absence. The institute, of course, started to break us, imposing upon us its rules and views on art. It was difficult to get on with certain of its characters, or even impossible, but in our third year Aleksei Gritsai (who didn’t especially like innovation but defended black sheep) joined the staff, and with him Dmitry Zhilinsky, to whom we were grateful our whole lives for his art, fortitude and gentlemanliness, and also Sergei Shilnikov, who taught us how to use our heads. And so we learned from each other, observing and adopting some things, rejecting others.

In 1989, I left the Pictorial Art Factory. I always talk about it with gratitude, because it gave me the opportunity of travelling the length and breadth of our multinational country, drawing every imaginable kind of harvest - cotton, apple, pear, grape etc. I was only allowed abroad in 1984, when I was 40, which was, unfortunately, rather late in the day for true ecstasy.

I did, however, travel to Western Germany, where Vladimir Semyonov, a wonderful collector and true lover of art, had brought together genuine masterpieces by artists from the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. He was the ambassador to Germany, he introduced me to various people and opened a path that had been hitherto firmly closed. I suppose it was then that I started travelling abroad, but that year, it was Eastertime, April 23, and in the little town, the church bells were ringing and in the living room, it smelled of footworn parquet, straight from my childhood. A rather different life had begun.

I work quite a lot, probably because I find the activity soothing; you forget about your misfortunes, or get annoyed at the fruits of seemingly fruitless work, or sink into thoughts of dear friends no longer with you.

In fact, I live so that my grandad and mama can be content. My mama was an example in every way for me - her intelligence, knowledge, her way of seeing both humour and tragedy. She was my angel and, when I lost her in 2002, I felt all the loneliness that can be imagined... yet still, she comes to me, she helps me, she tells me off. Those of our friends who have passed on also help us when times are especially hard.

I try not to lose my face, though these days I can’t always recognise it in the mirror, and all the same, I want to preserve something I don’t have to be ashamed of.

If I impart at least some joy to people, or if I rouse their interest, or annoy someone, then at least it means that I have touched their hearts, and it is for that, perhaps, that an artist works.

Natalya Nesterova. New York. 2016

Photograph by Yuri Rost

Every child that is born gets their genes from their parents and ancestors - that is the way God designed us.

I have always idolised my grandfather, the artist Nikolai Nesterov, and my mother, an architect who absolutely loved books and travelling. My father loved the mountains, something that, unfortunately, he did not pass on to me, but he did inspire some of my own travels.

For a long time now, I have made annual trips to France and America, the latter having become a second home to me.

I first visited New York in 1988 and was left stunned and bewildered. My old friend Mikhail Odnoralov had lived in New York for a couple of years or so already and knew the city inside out. He picked me up from my hotel and then, starting from his home near Delancey Street, we covered the whole city in a day and a night, dropping by little restaurants - a vibrant, sleepless world. We travelled to other cities, visiting cinemas and exhibitions. Misha always knew what was on, where and when. Since then, whenever I fly to New York and see Manhattan island rising in front of me from the car window, I think “I’m home”. Years have passed by, many friends have passed on, the city has changed, the Twin Towers have fallen - to this day, I wipe away tears whenever I pass the spot where they used to stand.

New friends have appeared, always willing to help me out. I will always be grateful to my first art dealer, Hal Bromm, to Maya Polsky with her gallery in the beautiful city of Chicago, to Alexandre Gertsman, with whom I worked, giving each other help and support in this city that has become something of a phantom for me, appearing and disappearing, bringing elation and desperation.

In France, I rented a beautiful studio in Paris, a former dance school located in the passageway of a courtyard whose walls were strewn with masses of ivy and Virginia creeper, the latter covered in green grapes in spring and crimson-red leaves in autumn.

Paris holds a place in my heart, along with every building, every bridge, the sky, the birds and the Seine, with its river boats twinkling with multicoloured lights in the evening-time, sending rays of light towards the riverside. A joy for the soul. It was here that my genes began to show themselves - together with my dear friends Tanya and Yuri Kovalenko I toured many small cities, going to listen to music in cathedrals, large and small.

I worked a great deal in the studio of Nicole, an artist and illustrator, probably because she was not afraid to work with fellow artists who were “barbarians, but admiring to the point of tears”.

Perhaps I will write about Paris sometime, although indeed my works in oil, rather than those of an epistolary nature, are quite enough - given that geniuses have already described this city. It lives, nonetheless, in my heart, and perhaps some tree or sculpture I have stolen a glimpse of slips out from time to time onto my canvases.

I began with my sense of gratitude and overwhelming love for my genes, which are to thank for my existence... And so they live on!

N. Nesterova May 15, 2021

The Art of Natalya Nesterova

Yuri Rost

We spent a long time searching for a background. We wandered around the yellow Summer Garden and other no less summery gardens, all with freshly cut green lawns and little white dogs lying on them. We walked around Moscow, around other cities, among men and women who looked preoccupied even in their leisure hours. We walked by the sea, by the bright sea, along the bright sand, and the people were in bright clothing, and all was tranquilly tense.

From time to time, birds appeared, not entirely unthreatening. Their wings entangled, but they did not fall, though they were heavier than air. Angels, though lighter than air, did crash down, threatening the lives of those they should protect. Numberless eyes spied over our unintelligent lives, and our transparent silhouettes were lit by leaden clouds, hanging uneasily in the atmosphere, while figures in uncomfortable poses hovered above the land. Above the lands, for various were the places of our sojourns, desires, joys, suffering and play.

Among these lands, one was familiar to the point of unrecognisability, where all that had long since happened was still happening, where He who was still to return had not yet left, where those by whom He was betrayed were still devoted to Him, where those who preached did not believe. And we saw that which was depicted in words bereft of words, and in the absolute silence, we heard what He said to the remaining 12, each in their place in their own square, separated from each other by the white boundary of the wall, yet we have not yet understood, not in the course of 2,000 years.

We wandered through time in our quest, often returning home to the space where different unknown women and men, rather more beautiful than ourselves, and completely knowable, ate, played cards, talked or simply contemplated. They paid us no attention, as if we were a background. Is it not so? Are not our wonderful lives, in this time as in any other, a canvas primed with the passions and flatness of being, upon which a great artist spreads his world? A living world, may it be noted.

The entire surface of the canvases painted by Natalya Nesterova is filled with the mysterious anxiety of anticipation. Allow your gaze to wander, even briefly, from the painting, leave it unobserved even for a second, and something of the utmost importance will have happened not only in the life of its characters, but also in your own life. Such is Nesterova’s talent. She clearly exults in certain states of canvas, although one is more preoccupied by the feeling that something inevitable may happen if we lingered in her world, leaving our own unattended.

Natalya NESTEROVA. Cyclists (1, 2). 2004

Oil on canvas. 140 × 100 cm (each)

Paradigm of Paradoxes and Implications

Alexander Rozhin

Natalya Nesterova’s art always contains a certain mystery of awareness and self-knowledge. Many worthy and well-known authors wrote about Nesterova’s works, such as art critic Valery Turchin, actor Aleksander Kaidanovsky, essayist and photographer Yuri Rost, art critics Alexander Morozov, Viktoria Lebedeva and Tatiana Kochemasova. And each of them wrote differently, expressing their feelings and perceptions of her meditative art. It is as if her paintings represent an entire metalanguage of gestures, symbols and signs, the conceptual meaning of which depends on the viewer’s sensual subjectivity, the power of their artistic imagination, their personal experience and, of course, the sanctity of their attitude towards art.

The scenes and characters in Nesterova’s paintings are fragmented memories projected onto new impressions. Some of them resemble the vintage realia of Italian Neorealism, while others would never fit such a description but form an emotionally and semantically independent line of creativity, where houses of cards are inhabited by strange creatures dressed either in shrouds or chitons numbered in a chaotic order (perhaps even beyond the artist’s volition).

Natalya NESTEROVA. Lupins. 2012

Oil on canvas. 80 × 100 cm

Some of the works evoke associations and parallels with the metaphysical attempts of the Italian masters de Chirico and Carlo Carra or the works of Surrealists Salvador Dali and Rene Magritte. But these are merely external connections, and not always even visual ones. Nesterova’s art lies beyond known trends and traditions, but its unique paradigm may well coincide with the specifics of the viewer’s individual perception of the world.

Perhaps Nesterova’s mindset is inextricably linked to the impressions of childhood and adolescence, to Charles Dickens’s unchildlike stories about children, which fired her imagination. We witness the contrasts and paradoxes of her perception of the world’s contradictions: from the “naive” delight of summer sea cruises and amusements to the tragic rejection of conventional laws and rules of life. It is no coincidence that the strong incompatibility of the universally significant and the personal is most palpable in Nesterova’s paintings. She is an artist with a dramatic and spontaneous nature, despite her self-absorbed and calm exterior. Created in one breath, her works demand a meditative immersion into the habitat of her visible heroes and fantastic creatures.

The image of “solitaire games” and “houses of cards” accompany and determine her creative path, her fate. Despite the seeming repetitiveness of the motif, it is always differently accentuated, and the author’s mood is its ultimate “tuning fork”. The brushwork is also far from being uniform, as evidenced by the barely noticeable unevenness in the brushstroke relief.

Nesterova’s rich array of colour is also quite unusual: it is based on several pigments, not on different colours of the palette. As for the semantic distinctness or the predetermined nature of the artist’s works, nothing is obvious here as well. Card games have long been and remain one of the most attractive subjects for art.

Solitaire as a method of fortune telling, of delving into the secrets of one’s fate, was, of course, reflected most prominently in the literary works of a long list of Russian writers, including Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy and Vladimir Nabokov. Nesterova emphasises psychological tension through multi-layered colours, their monotonous depth broken by occasional flashes of patchy brushstrokes.

The aesthetics of a number and a circinus, the unique geometry of spatial composition in opposing vectors of movement and in morphing some geometric figures into others - this ritual most likely occurs on a subconscious level, with an intuitive sense of time that can never be stopped, no matter what.

Natalya NESTEROVA. Catching Butterflies. 1981

Oil on canvas. 97 × 116 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Moscow, Paris, New York - the cities where Nesterova has lived and still lives - are merely reference points onto which certain visions are projected, visions that are, at times, amorphous and, at times, strange. Her living space is not the apartment or the artist’s studio, but the soul in a fragile invisible shell, tender and vulnerable. The visible simplicity of the painter’s canvases is deceptive and inaccessible to many. Its depth and ambiguity, which do not always readily lend themselves to verbal interpretation, are, for the most part, vague, like premonitions or dreams.

The fatal inevitability that constantly accompanies the tactile impulses of Nesterova’s emotional soul resembles the complex connection of the three simple cards, the story of Countess Anna Fedotovna and Count of St. Germain, as well as the incredible rumours surrounding them - all of which was romantically and mystically embodied in Alexander Pushkin’s “The Queen of Spades”.

Nesterova’s art shows the tragic relationship of the infinitely small and the infinitely great. For each of us, the infinitely small is undoubtedly smaller than we are, which allows us to experience an imaginary rational freedom; yet when we gaze on the infinitely great, the majority experience it as an insurmountable threat.

Nesterova unconsciously moves towards this unknown threat, as if dooming herself to some sort of sacrifice, which allows her to release herself from the sphere of her own complexes, thereby also freeing the viewer’s imagination.

Natalya NESTEROVA. Zoo. 2015. Polyptych (15 parts).

Oil on canvas. 90 × 70 cm (each)

In this context, one can, of course, expect Biblical subjects, which some of the characters of Natalya’s mystical and “Neoprimitivist” works morph into. We have Adam and Eve, the Last Supper and, finally, Noah’s Ark (her picturesque “Zoo”), where different species of the Earth’s fauna are gathered, as if emerging from the exotic fairy-tale works of Henri Rousseau. Nesterova’s mysterious world of images thus emerges, narrowing and expanding like the Peau de chagrin. It is simultaneously diverse and interconnected. The invisible connections seem to be maintained by the numerous geometric “formulas” that consist of triangles and trapezoids and are “woven” by the card figures or the domino tiles - the oppressed but invincible anonyms.

In the studio. 1990s

Photograph by Yuri Rost

Of course, in this space of the artist’s soul, there is a staircase to nowhere, up which a lonely human figure rushes towards the inevitable. This strange, mysterious and indefinite, brutal and amorphous world afflicts our imagination, especially when digital coordinates invade it out of nowhere, as if encoding and translating vibrant feelings into digital matrices. This, in my mind, is the paradigm of paradoxes, implications and finer feelings of the secretive, alluring, mystical and vivid art of Natalya Nesterova.

- GITIS: The Russian Institute of Theatrical Arts, Moscow

- MSKhSh: The Moscow Art Middle School, now known as the Moscow Central Art School of the Russian Academy of Arts

- The Surikov State Moscow Academic Art Institute of the Russian Academy of Arts.

Photograph by Yuri Rost

Oil on canvas. 120 × 80 cm (each)

Oil on canvas. 120 × 80 cm (each)

Oil on canvas. 105 × 70 cm

Oil on canvas. 80 × 120 cm

Oil on canvas. 75 × 90 cm

Oil on canvas. 90 × 90 cm

Oil on canvas. 170 × 110 cm (each)

Oil on canvas. 190 × 120 cm (each)

Oil on canvas. 145 × 160 cm

Oil on canvas. 145 × 180 cm

Oil on canvas. 100 × 70 cm

Oil on canvas. 100 × 120 cm

Photograph

Photograph

Photograph

Photograph

Photograph

Coloured pencils on paper. 20 × 16 cm

Photograph

Photograph

Photograph

Photograph

Photograph

Oil on canvas. 70 × 90 cm

Oil on canvas. 65 × 85 cm

Oil on canvas. 60 × 80 cm

Photograph

Photograph

Photograph

Photograph

Oil on canvas. 80 × 60 cm

Oil on canvas. 120 × 90 cm

Polyptych (13 parts). Oil on canvas. 100 × 70 cm (each)

Oil on canvas. 120 × 90 cm

Oil on canvas. 120 × 180 cm

Photograph by Yuri Rost

Oil on canvas. 100 × 80 cm

Oil on canvas. 90 × 60 cm

Oil on canvas. 75 × 100 cm

Oil on canvas. 100 × 70 cm

Oil on canvas. 90 × 120 cm

Oil on canvas. 80 × 110 cm

Oil on canvas. 80 × 100 cm

Oil on canvas. 80 × 60 cm

Oil on canvas. 100 × 70 cm

Oil on canvas. 100 × 150 cm, 100 × 80 cm

Oil on canvas. 100 × 150 cm, 100 × 80 cm

Oil on canvas. 75 × 95 cm

Oil on canvas. 90 × 90 cm

Oil on canvas. 60 × 80 cm