A Journey to the Land of Colour

In the spring and summer of 2021, the Tretyakov Gallery is set to host an exhibition of work by the colourful and original artist Tatiana Mavrina (1900-1996).

Seize the Moment!

In fact, her real name was Tatiana Lebedeva. She started signing her paintings Mavrina in the 1930s - Mavrina was the maiden name of her mother, who was of old aristocratic stock. From 1921 to 1928, she studied at VKHUTEMAS-VKHUTEIN, where Robert Falk was her most important teacher. Nonetheless, there is a certain originality to her early works that makes itself felt just as much as the influence of Falk and her favorite French artists (Matisse, Derain, and Bonnard). The paintings of the young artist were stamped with a clear sense of humour and, in terms of their mood, they are close to the work of the writers and graphic artists grouped around the newspaper “Gudok” (“The Whistle”) in the 1920s. In the words of our contemporary, the writer Dmitry Bykov, dedicated to the authors of “Gudok”, “This was, to a large degree, an attempt to joke in an unfunny world, to smooth over its paradoxes. A shining, conciliatory force in a world that was becoming sickeningly serious.”[1]

At the end of the 1920s, many of the young artist’s future friends and collaborators were working at “Gudok”: Nikolai Kuzmin, Daniil Daran, Sergei Ras- torguyev. These men, along with Vladimir Milashevsky, formed the core of the group “13”.[2]

Sukharev Tower. 1930

Oil on canvas. 81 × 66 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

With her dynamic and satirical style, Mavrina fitted organically into this group. Most of its members were drawn to graphic art, although nearly all of them were painters. The most important thing for all of them, however, was to fix on paper the tempo of a contemporary life that was changing with every passing hour. The “fast drawing” technique, when sketches were made from life with neither corrections nor pauses, became a priority for the 13. They often used the quick “wet-on-wet” watercolour technique - i.e. they applied watercolours to wet paper without any pencil preparation. In their efforts to fix the unique moment on paper, the group’s artists often managed to capture something fleeting and beyond human control, to sense a certain energy of the diverse, electrifying and alarming life in the late 1920s to early 1930s. Furthermore, the speed of their drawing allowed time itself, as it were, to become the subject of their work, thus avoiding the pathos and shade of elation that could already be felt in Soviet art.[3] In general, rapid-fire drawing was a technique common to many artists of the era, “from Mir Iskusstva’s Dmitry Mitrokhin to the former Cubist Vladimir Lebedev. But it was only the 13 group that consciously adopted this light, ‘sketchy’ style of drawing as a creative principle or programme”.[4]

Moscow Landscape with Open Carriage. 1922-1925.

Watercolour, sauce, wet brush and white оn grey paper. 29.7 × 37.6 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

This was a matter of principle for Mavrina while she was a member of the 13 group, but she continued working in this manner even in later periods, in both her graphic art and her painting.[5] She was interested in modernity, the urban dynamic that pulled into its orbit not only the moving parts of a city but even what we would normally consider static elements. Streets, bridges, buildings all seem to come alive in their own way in her cityscapes, sometimes huddling together, sometimes as if shrinking away from each other. The Moscow of Mavrina’s paintings often comes across as some sort of special space in which forms exist according to their own laws, laws that have little in common with the laws of physics. In terms of colour, the further away an object is, the lesser the extent to which it obeys the laws of optics. Colour in and of itself always inspired a kind of childish enthusiasm in the artist. A colour, its movement and its interactions with other colours within a space cause everything she sees to be transformed into a real chromatic extravaganza on paper or canvas. Her favourite colour was always red.

House with a Red Roof. Late 1920s.

Watercolour and gouache. оn paper. 35.6 × 26.4 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

However, Mavrina only painted oils on canvas for just over 10 years. Her work in this field comprises canvases of modest proportions in which the density and intensity - but also the elegance - of the colouring imbue her subjects with meaning. That said, the artist’s style did change in the course of that decade. The canvases of the early 1930s are carried out in the style of ‘naive’ Primitivism. They are comparable to an extent with her early “vandalistic” graphic pieces, which, in turn, owe much to her feeling of innocent wonderment in the face of life’s unexpectedness and inconsistency. In her works from the middle of this decade, her style of painting becomes more relaxed and there is a greater sense of the Impressionism that was then making inroads in Soviet art. The artist recalled of one of her paintings in which she drowned all the details in a sort of “colour-mirage”: “the general impression was one of festivity, although the scene was one of drought. The rye was killed off by the drought, all that was left was cornflower! I still remember the aura of crimson heat around the clouds. I painted them like that, but I didn’t highlight ‘the misfortune’ then, and I don’t now.”[6]

For Mavrina, colour was never an aim in and of itself. For her, as for many artists of her generation, colour was not something linked only to generalised forms, but to narrative motifs as well. In her portraits, these are, more often than not, a gesture; in her landscapes and urban scenes, they are movement, whether it be the movement of a train, a car, or a gust of wind. Her characters move with an ostentatious lack of speed, as if the artist wants to make the process as “natural” as possible. They often look rather angular and, at times, Mavrina includes among that number herself, her husband - the artist Nikolai Kuzmin - friends and relatives. They all fit naturally into the integral hypostasis of her canvases and graphic works, an essence that, the further it recedes, the more “scorching” and “shining” it becomes.[7]

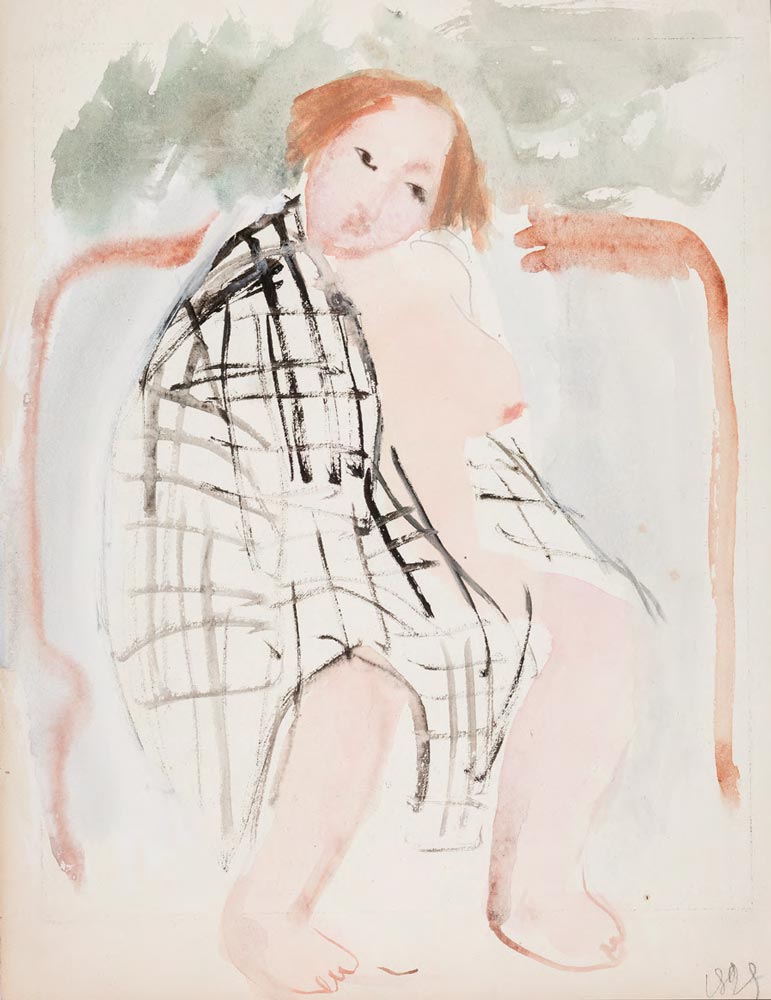

Nude in a Checkered Bed Sheet (In a Bathhouse). 1929

Watercolour, indian ink, gouache and graphite pencil оn paper. 36.3 × 27.3 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

As a rule, Mavrina’s early graphic art is brighter and airier than her painting. However, here too you can feel her heightened attention to colour and its variations, to the interactions of watercolour dabs blooming across white or tinted paper. She worked mainly in watercolours at that time, using heavy gouache now and then to diversify the effect of the same colour. Whatever the medium, however, Mavrina felt herself to be primarily a painter, who most enjoyed working with dabs rather than lines. Her favourite genre was the cityscape, along with, of course, still-lifes of flowers, intimate portraits and nudes. That said, she was able to infuse any genre she worked in with a large measure of her playful archness, humour, ingenuity and wonderful painterly mastery.

Defend Moscow!

In July 1941, when Moscow began to suffer bombing raids, Mavrina moved with her husband and mother to the historical suburban town of Zagorsk (now Sergiev Posad), where they lived in a house occupied by the family of one of her sisters. By spring 1942, however, they had returned to Moscow. There, they faced a hungry existence in the depopulated city, with hours spent queuing for frost-nipped potatoes, problems finding firewood and all the other unhappy details of life in wartime. Working certainly was not easy, but it was at precisely that time that Mavrina found new stimuli for her creativity.

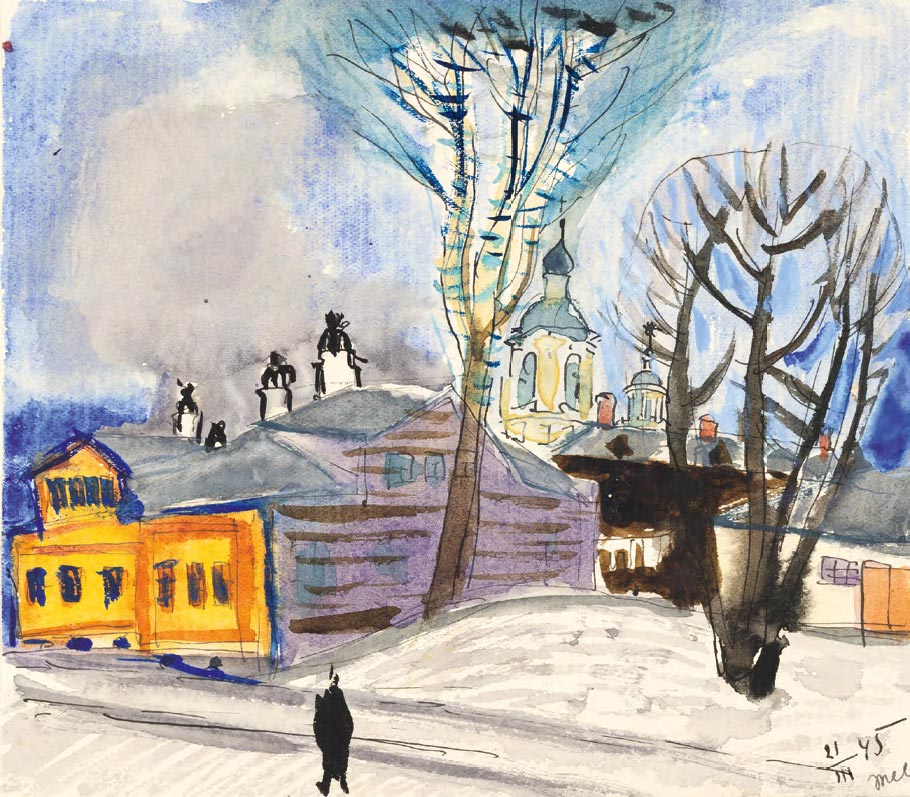

The Third Meschanskaya Street. Moscow. 1945.

Indian ink, pen and watercolour on paper mounted on paper. 13.9 × 15.3 cm

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The first of these stimuli appeared, as she recalled, “in 1941, among the wonderous gayness and beauty of Zagorsk (despite the war and in spite of everything, the towers stood bright pink, the ancient churches breathtakingly beautiful)”[8]. Secondly, Mavrina also discovered for herself the bold and naive art of craftsmen from Gorodets, a small town on the Volga not far from her hometown of Nizhny Novgorod. It was in Zagorsk that she encountered once more the almost forgotten art of painting on wooden panels. Mavrina managed to make new copies of the original paper impressions of Gorodets panels kept by the toy-painter Ivan Oveshkov, which would later be lost. She always remembered her meeting with Oveshkov and the Gorodets panel paintings as a miracle and, from then on, the style of popular craftsmen became part of her own signature style.

In 1942, Mavrina began a graphic cycle dedicated to Moscow’s historic buildings. The age-old beauty of Zagorsk awoke an interest in the artist for the capital’s ancient monuments, accompanied by a sense of alarm that all this beauty was in danger of being razed to the ground.[9] The first pieces within the series date to autumn 1942. “In Moscow, I began to paint bit by bit, without drawing any attention to myself,” she remembered. “The first church was one outside the city limits beyond Ostankino [...] Then I got bolder and started painting streets, at first the ones close to home, then ones further away. All the time on foot. I often made the initial sketches blindly, running the pencil along the paper in the pocket of my overcoat, before completing the sketch from memory in the stairwell of some random block of flats and finishing it off at home with pen and paint. I drew nonstop, every day, and painted with watercolours and gouache at home.”[10] In 1943, she took the precaution of obtaining a licence signed by various officials and no longer feared, to the same extent, being caught in such reprehensible activity and arrested as an enemy agent.

At one stage, Antonina Sofronova, Mavrina’s older friend and fellow member of the 13 group, was attracted by the motif of the melancholy walks of a lonely thinker who had once lived in Moscow and now, having returned, wanders the deserted streets of the capital, at once recognising and failing to recognise them. Melancholy was always alien to Mavrina and the motif of loss was transformed in her work to an idea of protection. Her drawings from the tragic year of 1942 are astounding in their disciplined colouring and the dramatic tension of their emotions. Then the city begins to slowly brighten.

Mavrina draws tirelessly, before bringing churches, monasteries and ancient buildings to life with watercolours. Pen-and- ink sketches not only fix the outlines of buildings, but are somehow called upon to underline the fragility of whimsical architectural forms in wartime and the the ornate, fluid watercolours cannot fail to awaken the soul to a sense of joy and a hope that these wonders might be preserved. In Mavrina’s sketches, the city seems frozen in its inexpressible beauty while the people slide noiselessly along its streets as if fearing to wake it from its regal slumber.

Past the Island of Buyan to the Kingdom of Saltan

Mavrina continued this work until the jubilee year of 1947. Postwar Moscow gradually ceased to be a source of inspiration for her - clearly, she could no longer make out any inner development, despite the outward burst of restoration taking place within the city. For Mavrina, as for many thinking people of the time, the period of “Late Stalinism” (1946-53) was likely perceived as something viscous, isolated and unproductive, despite its coming immediately after the triumphant end of the Great Patriotic War. The jubilation of victory was somehow transformed very quickly: it seemed as if “there was no light at all”.[11] The artist herself remembered this period as a very difficult one, when she and her husband, both labelled “formalists”, had to “make technical medical posters,” as she put it, “a task to which we were ill-suited and which little interested us.”[12] Furthermore, Mavrina left oil painting behind forever for a variety of reasons during the war. From here on out, gouache with watercolours and tempera on thick paper become her faithful helpers in the expression of her thoughts and moods. She experimented in a range of genres: creating animated films and film strips, painting on birch bark, all the while continuing her easel graphic works. At the end of the 1940s, Mavrina returned to working in book design, but this time, she focused on editions for children.[13]

Spring Cat. 1961-1964.

Gouache, tempera, watercolour and gold paint on handmade paper. 38.7 × 53 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

In her early fairy-tale pieces, there is still a yearning to unite life and fairy tales by using perspective in her compositions, but, gradually, in her books, space becomes more and more ‘unreal’ and flat, while scales become more jumbled. Everything, whether distant or close, is represented in equally vivid colours. This is in the manner of her beloved French painters from the beginning of the century and of her friends and herself in the 1930s. During the Krushchev Thaw period, artists began to rediscover the traditions of Modernism and the Avant-garde from the 1920s and 1930s. Mavrina was also attracted by this tendency, but her postwar work was also enriched by her references to popular craftsmen in whom she noticed a striving to enrobe the down- to-earth in a brighter and more festive garb. “They possessed some gift for seeing only beauty around them, along with the ability to portray it, to ‘scrawl it with paints’ so that everyone could admire it.”[14] It is not only the figurative richness of folk art that attracts Mavrina, but its technical element too. “At that time, I, who had been formed ‘in the French manner’, was enchanted with a completely different, previously unknown to me technique, a completely different method of applying colour, which was incredibly resonant. Despite a limited palette, it managed to avoid both ambiguity and ups and downs.”[15]

In the fairy-tale world of Tatyana Mavrina, there is no place for peril nor anything frightening at all. She addresses gentle folk tales and the works of Pushkin, which are similar to them in spirit. When illustrating a tale, the artist creates a “resonant noise”, expressed in both buoyant tones and in the figurative organisation of the imagery. It is not uncommon to come across a unified composition on the covers or spreads that then spills along the pages of the book in variously sized “stamps”, as she put it, accompanied all the way by merry, patterned decorative elements. Colour is everywhere intense, yet, at the same time, appears in a multitude of the most varied and exquisite shades and combinations. Just as expressive and numberless are the shades of kindness and humour with which the artist endows the characters of these books.

Her beloved animals appeared from time to time in her pre-war work also, for Hoffman’s Tomcat Murr is all but the doppelganger of the learned cat from Pushkin’s Ruslan and Lyudmila that she so adored. In her time, she portrayed Hoffman’s character in an anthropomorphic black-and-white figure as if showing that he was, in the words of Mikhail Bulgakov, “no ordinary cat”. In this later period, her cats appear in the guise of strange, exuberant beasts that are, nonetheless, recognisable as cats, although nothing but whiskers, eyes and ears remain in the image. The artist’s endless stream of creativity was not satisfied with purely fairy-tale subjects, however, and soon spilled out into other works.

Wondrous Cities

From the very first postwar years, Mavrina regularly travelled to historic Russian cities, more often than not with Kuzmin, but sometimes alone. These trips, among whose key motivations was the desire to once more “defend beauty”, continued to the end of the 1980s. Due to the new wave of religious persecution during Krushchev’s rule, there was a real danger that the ancient churches of historic cities that had survived the first wave of “militant atheism” in the 1930s would now be lost. The contemporary threat came not only from demolition, but also from dereliction and slow disintegration. In the 1960s, people began to pour into large population centres and historical monuments in smaller towns and villages gradually decayed and disappeared. The policy of modernization led to the destruction of the environment and alteration of landscapes that were familiar to Mavrina from her childhood. Her diaries contain many regretful passages on this subject. “Everything that I love and paint will disappear, is already disappearing, is in need of preservation. I love and delight in landscapes with historic architecture or villages, or even fields with woodland.”[16]

Rostov Veliky Kremlin at Night. 1965.

Watercolour, gouache, silver paint and Indian ink on handmade paper. 38.2 × 55.1 cm

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

For Mavrina, historic towns were joyful, festive and authentic places. The manner in which she portrayed them changed with time. The wondrous cities of the 1950s were not quite fairy tale; their spaces were constructed in accordance with the laws of perspective. Joyful, colourful images of people and buildings on a background of winter landscapes in the spirit of Boris Kustodiev or Konstantin Yuon give these works a bright and jolly mood.

With time, Mavrina condenses the space in her paintings more and more intensely. Objects at different distances from the viewer are painted in more or less identically intense colours, but with different hues. The sense of space is very prominent, as “the composition unravels like a pattern on the surface, but the relation of colour masses and accentuated lines conveys the dynamic of space - the twisting of a road, the growth of trees, the flight of a bird, the flow of a river.”[17]

Mavrina is attracted not only by ancient monuments, but also by the vicissitudes of the people who live in these towns. Bag-laden old biddies, half-drunk loungers, postal workers and women of fashion all appear more and more prominently in her compositions, at times brought to the foreground. The cityscape or landscape gains an additional aspect of genre art without losing its fairy-tale essence.[18] Sometimes, these characters seemingly abandon their hometowns and transform into portrait subjects or, more rarely, into the heroes of their own genre scenes.

A star-strewn abyss yawns wide

In the 1960s and 1970s, recognition was at last bestowed on Mavrina: she was snowed under with orders from publishers, and museums and galleries begin to hold exhibitions of her work. Despite her age, the artist worked at a prodigious rate and turned to new themes. In an article from the 1970s called “On Ancient Russian Painting”, Mavrina recalled how, at some stage before the war, she visited the Tretyakov Gallery “to see, of course, the “Jack of Diamonds”, and went upstairs to where the icons then hung...”[19] A new world opened up before her eyes. The icons astounded her with their unfamiliar artistic language and their ability, as she wrote, “to portray the unknown, otherness, the unseeable.”[20] In the years that followed, Mavrina often worked at the Tretyakov Gallery, making loose copies of the icons. Even before the war, Mavrina and Kuzmin had begun collecting icons, something that turned into a lifelong activity. Like many of her generation, Mavrina saw in icons an ideal of beauty and harmony, but, at the same time, she could discern in them something “unseen” and “unportrayable”.

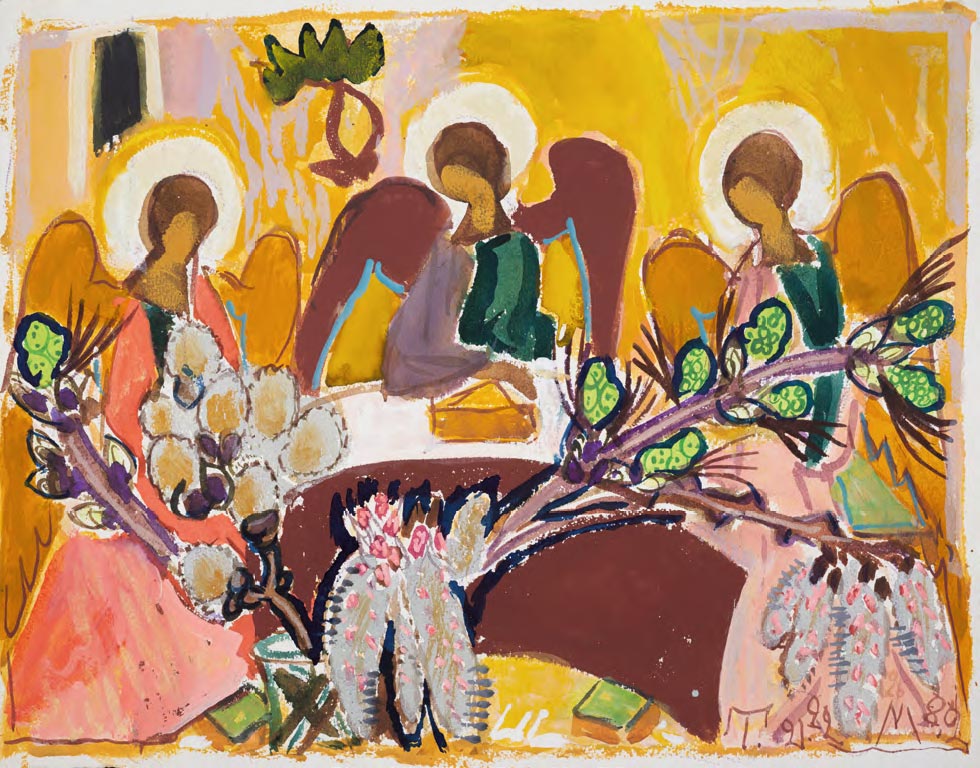

In her later years, Mavrina created a graphic cycle comprised of free interpretations of icon images. In the foreground of the icons, she placed bouquets of flowers, the branches of trees with budding spring leaves, or the squirrel from Pushkin’s tale. In doing so, the artist united two eternities - nature’s infinite death and rebirth and the “unseen” basis, which, as she understood it, stood behind the eternal vortex of the natural world.

Trinity. 1980.

Watercolour, tempera, silver paint and gouache on handmade paper. 38.3 × 48.2 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

In the 1990s, Mavrina rarely ventured from her home, but kept a firm hold on her paintbrush. Working from memory, she painted landscapes with huge flowers, as well as what she saw around her, what she could observe from her windows. During this period, the “heavenly and profane” are once again brought into contact. Most commonly this takes the form of potted flowers, standing on the windowsill, or sprouting bulbs and apples lying nearby. Beyond the windowpane, there are trees illuminated by neighbouring windows and, above all this, the unfathomable blue of the night sky.

- D. Bykov, “100 Lectures on Russian 20th Century Literature” [“100 lektsiy o russkoy literature XX veka”], in 2 vols., vol. 1 in: Time of Earthquakes 1900-1950, (Moscow: Eksmo, 2018), p. 282.

- The group was so named by its organisers in reference to the number of permanent exhibitors.

- “A sense of movement! We felt the need to return drawing to its first principles: the movements of the hand, threading the line, leaving a trace! The art of drawing had become overgrown with layers, affectations and a purposeful artificiality.” Quoted from: V. Milashevsky, “Yesterday, the Day before Yesterday... Reminiscences of an Artist” [“Vchera, pozavchera... Vospominaniya khudozhnika”], p. 273.

- Yu. Gerchuk, “Tatiana Mavrina and Anatole France” [“Tat'yana Mavrina i Anatol' Frans”], in: Tatiana Mavrina. Illustrations for Anatole France's novel “At the Sign of the Reine Pedauque” [Tat'yana Alexeevna Mavrina. Illyustrat- sii k romanu Anatolya Fransa “Kharchevnya korolevy Gusinye Lapy”]. From the collection of Mark Ratz, (Moscow, 2004), p. 4.

- It is noteworthy that we can often see advance signs of the future fairy-tale illustrator even in the work of the 1930s - be it a cottage with “ears” and “eyes”, a building or a tree that begins to literally effuse light, or an intentional lack of correlation in sizes, where birds in the sky seem bigger than humans on the ground.

- Quoted from: A. Sheludchenko, “T. Mavrina. Intoxicated by Colour.” [“T.A. Mavrina. Uvlechennaya tsvetom”] in: T. Mavrina. Etudes on Art. Materials for a Biography of the Artist [Mavrina T.A. Etyudy ob iskusstve. Materialy k biografii khudozhnika], p. 304.

- V. Kostin, p. 7.

- T. Mavrina, “Gorodets Painting” [Gorodetskaya zhivopis’] in: T. Mavrina. Etudes on Art. Materials for a Biography of the Artist [Mavrina T.A. Etyudy ob iskusstve. Materialy k biografii khudozhnika], pp. 51-52.

- “During the war, riding a bus along Sretenka Street,” she recalled, “I saw a 17th-century cathedral, something right out of one of Gra- bar’s books. I saw the entirety of its age-old beauty. And this could be destroyed by the bombing! I had to draw it, while it was still standing.” Quoted from: A. Sheludchenko, “T. Mavrina. Intoxicated by Colour” [“T.A. Mavrina. Uvlechennaya tsvetom”] in: T. Mavrina. Colour Exultant: Diaries. Etudes on Art [Mavrina T.A. Tsvet likuyushchiy: Dnevniki. Etyudy ob iskusstve], (Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya, 2006), p. 20.

- T. Mavrina, “Moscow. Forty Forties” [“Moskva. Sorok sorokov]. Ibid, p. 354.

- Ye. Dobrenko, “Late Stalinism. Aesthetics of Politics” [“Pozdniy Stalinizm. Estetika politiki”], in 2 vols., vol. 1 (Moscow: Novoye Literaturnoye Obozreniye, 2020), p. 12.

- Diary entries from the artist’s archive. Quoted from: A. Sheludchenko, “The Literary Lukomorye of the Artist Tatiana Mavrina” [“Knizhnoe lukomor’e khudozhnitsy Tat’yany Mavrinoy”], pp. 259-260.

- “I had the idea of working on fairytales during the war, when I was living in Zagorsk... In my mind’s eye, I purposely replaced the weathervanes atop crumbling spires with Pushkin’s Golden Cockerel. But I did not start my task until I had had wandered the streets of Moscow to my heart’s content, until I had travelled the historic cities of Russia, scrutinised folk art in museums and villages, sketched everything a hundred times.”

- T. Mavrina, “Gorodets Painting” [Gorodetskaya zhivopis’] in: T. Mavrina. Etudes on Art. Materials for a Biography of the Artist [Mavrina T.A. Etyudy ob iskusstve. Materialy kbiografii khudozhnika], p. 48.

- Ibid, p. 52.

- T. Mavrina, “Diaries” [“Dnevniki”] in: T. Mavrina. Colour Exultant: Diaries. Etudes on Art [Mavrina T.A. Tsvet likuyushchiy: Dnevniki. Etyudy ob iskusstve], p. 127.

- N. Dmitrieva, “Tatiana Mavrina. Graphic Art. Painting” [“Tat’yana Mavrina. Grafika. Zhivopis’”], (Moscow: Sovietsky Khudozhnik, 1981), pp. 11-12.

- In the text accompanying her 1970 album “Zagorsk”, Mavrina wrote: “I always loved and still love to include in landscapes of the Lavra various buildings and streets, and venomously blue kiosks, brighter than the sky, or intolerably blue bread trucks and random people with bags [...] But these “second-rate people”, or rather masters of the earth - for there are more of them - they are for me more interesting, more Russian; how much more interesting is the provincial Empire style, the fantastical cottages of homespun architects, than the capital’s beauties and princely chambers.” Quoted from: A. Shelud- chenko, “Tatiana Mavrina’s Books of Travels” [“Knigi Puteshestviy Tat’yany Mavrinoy”] in: On Books: Bibliophiles’ Magazine No. 3 (47) [Pro knigi: Zhurnal bibliofilov № 3 (47)], 2018, pp. 63-66.

- T. Mavrina, “On Ancient Russian Painting (Our Collection)” [“O drevnerusskoy zhivopisi (Nasha kollektsiya)”] in: Colour Exultant: Diaries. Etudes on Art [Tsvet likuyushchiy: Dnevniki. Etyudy ob iskus- stve], p. 314.

- Ibid, p. 315.

Oil on canvas. 71 × 48.5 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Indian ink and brush on paper mounted on paper. 29.5 × 24.3 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Indian ink and brush on paper. 31.2 × 29.3 cm

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Indian ink and brush on cream-coloured paper. 14.6 × 20.4 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 68 × 68 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 65.5 × 80.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Watercolour on paper. 29.6 × 38.3 cm

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Watercolour and bronze paint on paper. 43.8 × 31.8 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Indian ink, pen, brush, watercolour and white on paper. 14 × 19 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Watercolour, white, ink, pen and wax pastel on grey paper. 28.8 × 21 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Watercolour, gouache, Indian ink and pen on paper mounted on paper. 28.7 × 20.7 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Indian ink, pen, watercolour and white on light blue paper. 28 × 19.5 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Watercolour, white, Indian ink, pen and wax pastel on grey paper. 28 × 20.1 cm

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Watercolour, gouache, Indian ink and pen on paper mounted on paper. 20.8 × 28.7 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Watercolour, gouache, Indian ink and pen on paper mounted on paper. 24 × 33.5 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Indian ink, pen and brush on paper mounted on paper. 32.5 × 24.3 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Indian ink, pen and brush on paper. 34 × 25.2 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Watercolour, white, brown Indian ink and lacquer on paper. 31.7 × 36 cm.

Vladimir Dahl State Literary Museum, Moscow

Pastel and white on black paper. 32.2 × 25 cm

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Gouache and tempera on handmade paper. 53 × 38.5 cm

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Indian ink and pen on paper. 19.5 × 25.1 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Indian ink and pen on paper. 20.4 × 28.6 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Tempera, watercolour, silver paint and blue pencil on paper. 40 × 54 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Watercolour, gouache, tempera and pastel on handmade paper. 39 × 54.3 cm.

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Gouache, tempera and silver paint on handmade paper. 38 × 59 cm

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Watercolour, oil and white on paper. 51.7 × 37.7 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Watercolour, white, tempera and wax pastel on handmade rag paper. 38.2 × 45.4 cm

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Tempera, gouache, silver paint and pastel on paper. 52.6 × 38 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Watercolour, gouache and oil on paper. 39.9 × 51.5 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Tempera, watercolour, gouache and pastel on paper. 39 × 50.7 cm.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Gouache, watercolour and pastel on paper. 38.3 × 49 cm

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow

Gouache, tempera, silver paint and watercolour on handmade paper. 51 × 39 cm

Aleksander Sheludchenko Collection, Moscow