Moscow State Stroganov Academy of Design and Applied Arts Museum

The Stroganov Academy Museum is one of the most fascinating and unique museums in Russia. Founded in 1864, during Viktor Butovsky’s tenure as director of the Stroganov School of Technical Drawing (later to be renamed “academy”), the museum served to “advance the development of original creative talent and skills among the working classes.” The museum, located in a separate building at 24 Myasnitskaya Ulitsa, opened its doors on April 171868 and became Russia’s first museum to focus on the history of decorative and applied arts throughout the world, from antiquity to modern times. Still, the museum’s primary goal was to collect the works of Russian decorative art, in line with the Stroganov Academy’s original purpose to preserve and advance Russia’s rich artistic tradition.

Current exhibition at the Moscow State Stroganov Academy of Design and Applied Arts Museum. Photograph

The idea to create such a museum in Moscow took root long before the Stroganov Academy Museum was established; the Academy's founder, Count Sergei Stroganov promoted it as early as 1826, when he published an essay in “Vestnik Evropy” (“European Herald", issue 8) called “Regarding the need to provide training for artisans and establish a drawing school for them in Moscow”. Stroganov pointed out the need to “nurture national creative forces and general education as the source of energy for industrial development, and create a collection of models and samples to enhance craftsmanship and creativity in applied arts.”[1]

The Stroganov Academy Museum developed hand in hand with the school itself, which was founded in 1825 by Count Sergei Stroganov to “teach drawing as it relates to decorative and applied arts”. In 1860, dramatic changes took place in the life of Count S.G. Stroganov's 2nd School of Drawing, which was merged with the 1st School of Drawing at the Meshchansky Branch to form the Stroganov School of Technical Drawing, with a new charter and training for "draftsmen and decorative pattern designers for factories and workshops." In 1861, the historian Viktor Butovsky was appointed director of the restructured Stroganov School of Technical Drawing (an economist by trade, Butovsky was very well connected among Russian and Western industrialists). In this role, Butovsky made a great contribution to the development of applied and decorative arts education, as well as the revival of folk and ancient Russian artistic tradition. He led the Stroganov School of Drawing through one of the most important periods in its history.

This was the time when the School prioritised the study of Russia's ancient artistic heritage. Students copied objects of folk art, ceremonial religious objects, decorative patterns and headpieces in Russian illuminated manuscripts, which were all seen as cornerstones of the national movement in art. As part of the training, students went on expedition trips to Russia's oldest towns, such as Vladimir, Suzdal and Novgorod Veliky [Novgorod the Great], where they made plaster copies of ancient church architectural ornaments and casts of traditional household objects, as well as copying old Russian ornamental patterns.

It was the objects brought back from those expeditions that made Butovsky think that the School of Drawing should have its own museum dedicated to decorative and applied arts, not unlike the Museum of Manufactures (now the Victoria & Albert Museum) in London, which was founded in 1852 and was dedicated to the history of both the arts and manufacturing.

On January 17, 1864, Emperor Alexander II allowed the Stroganov School to start fundraising for the new museum, and personally donated a parcel of land measuring 3,600 square sazhens [apr. 16,400 m2] along the Myasnitskaya Ulitsa, along with existing buildings. Large donations began to pour in from merchants and patrons of the arts, among them M.G. Soldatenkov, A.A. Skorospelov, Khadzhi-Konsta, Savva Morozov, K.S. Popov, the brothers Botkin, P.A. Smirnov, I.I. Khludov and 40 other industrialists who resided in Moscow. A total of 109,984 rubles were raised and spent in part on the building for the new museum and in part on acquisitions.

Exhibition hall at the Stroganov School Museum of Applied Arts in Myasnitskaya Ulitsa, Moscow. Old Russian Art Hall. Photograph

The Stroganov Museum began building its collection by acquiring Old Russian folk art; at the same time, donations of artefacts flowed from the museum's many patrons. Among them were D.P. Botkin, P.P Vyazemsky, M.V. Kochubey, P.A. Kochubey, V.L. Naryshkin, Paolo Troubetzkoy, P.D. Saltykov, E.A. Ukhtomsky, E.I. Miussar, and many others with a lifetime commitment to philanthropy.

Alexander II gave the museum one of the most important gifts it ever received, a 140-piece collection of Russian and Western European ceramics and porcelain manufactured at the Imperial Porcelain Factory in St. Petersburg, as well as at the Sevres, Meissen, Berlin and Vienna royal factories. In 1899, the Stroganov Museum of Decorative and Applied Arts was named after Alexander II.

Tea service with fête galante paintings. Meissen porcelain factory. Mid 18th century

Porcelain, overglaze polychrome painting, gold plate

At its inception, the museum also received a large collection of Asian art from the heir to the Russian throne, the future Emperor Nicholas II. The gift included examples of Japanese lacquerware, furniture, ceramics and vases. Later on, many members of the Russian Royal Family made donations to the museum, including Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna, who was the patron of the Stroganov School of Technical Drawing, and Grand Dukes Sergei Alexandrovich and Vladimir Alexandrovich.

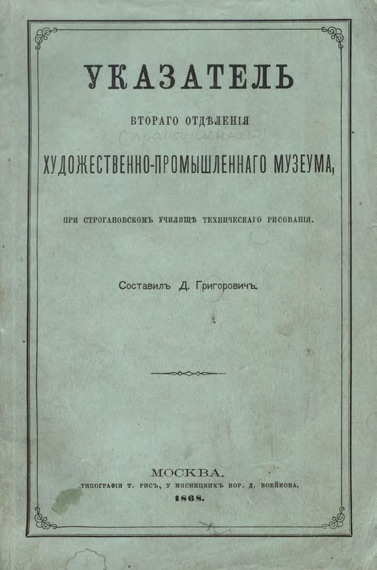

Dmitry Grigorovich, a famous Russian writer who attended the Stroganov School of Drawing as a youngster in the 1830s, credited it with giving him a lifelong love for the arts. He donated a priceless collection of Western European furniture from the 15th to 17th centuries and compiled the museum's first directory, which was published when the museum opened its doors in 1868.

When the Stroganov School of Technical Drawing first welcomed visitors to its new museum - the school's own students were among the first ones - the collection was divided into three topics: the arts proper, manufacturing and natural history; the total number of exhibited items reached 3,000. It was at the museum that “students, craftsmen, manufacturers and anyone who was interested in it could study artefacts from all over the world that included pottery, textiles, furniture, carvings, enamels, glass, crystal, wallpaper, decorative objects, ironwork and engravings."[2]

Directory of the Design and Applied Arts Museum. By D.V. Grigorovich. 1868

The museum played an important role in the training process at the Stroganov School of Technical Drawing - every day, classes took place in its halls, as the students learned to measure, copy and sketch. This practice reflected the basic principle of learning “through copying original works of art" that the school practiced in the late 19th century. Studying artefacts at the museum was the first step in learning the history of world art and shaping the students' artistic taste. At the same time, constant contact with the works of Old Russian art and decorative folk objects taught them to love and respect their “unique national artistic heritage." To this day, the Stroganov Academy keeps up this beautiful tradition and always includes classes at the museum in the curriculum.

Along with hosting classes, conducting research and publishing, the museum engaged in creative work by organising a variety of workshops, at which students trained in making woven and printed textiles, creating sculpture and painting pottery, porcelain and faience; chromolithography and electrotyping workshops engaged professional lithographers.

Later on, workshops began to sell their students' works to the public, as well as showing them at both national and international exhibitions - the Stroganov School of Technical Drawing was an active participant.

Thus, the school received a diploma for the ceramic objects it showed at the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia in recognition of their unique national character. The school was also honoured with a diploma for its participation in the 1878 Paris World Fair. Thanks to these exhibitions, the Stroganov School gained wide recognition for its work, both in Russia and abroad, in Europe and North America.

Certificate of Award from the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia for ceramics (ornamental clay tiles) presented by the Stroganov School Museum of Applied Arts

In 1892, the school moved to a new building at 11 Rozhdestvenka, which had been renovated by the architect Sergei Soloviev for that purpose. As a result, available museum space was expanded and was now comprised of 10 halls, each of which was dedicated to a particular historical period.

Ancient and Old Russian art was allocated a total of three halls, to accommodate the museum's most extensive and interesting collection. These halls offered a chance to see everything that represented Russian antiquity, including examples of wooden household objects, carved wood, pottery, hammered copper, silver and enamelled artefacts, a collection of glass objects, Russian silk fabrics, embroidery, lace, and traditional folk costumes.

Another hall was dedicated to ancient art and housed plaster and bronze copies of original sculptures, electrotype copies and original works of ancient Greek art, including vases, glass vessels and terracotta as well as Etruscan masks.

The art of Medieval Europe, the Italian Renaissance, various French styles and Asian art were each exhibited in a designated hall. Another hall showcased examples of contemporary commercial art, representing its best artistic achievements and greatest historical value. This section housed the icon of St. Alexis, the Metropolitan of Moscow and All Russia, in a silver-gilt setting decorated with enamel, and an icon oil lamp, made in the Russian Revival style by the Pavel Ovchinnikov jewellery house, a gift to the Stroganov School. Modern-day fabrics, majolica, porcelain and glass products were also exhibited in this hall.

In 1896, Nikolai Globa, a painter and educator, was engaged as director of the Stroganov School of Drawing, an appointment that ushered in a truly magnificent era in the school's history. Globa served as director of the museum as well and worked relentlessly to preserve and grow its collection. At the same time, Stanislaw Noakowski, an art historian and renowned architectural landscape artist, was the museum's custodian.

Nikolai Globa, Director of the Stroganov School of Drawing and the Emperor Alexander II Museum (1896-1917). Photograph

The museum continued to grow its collections of Western European and Asian art. At the end of the 19th century, the Stroganov Museum commissioned special workshops to make copies of a number of works from the largest European museums, including the Louvre and the National Library in Paris, the Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon, the Vatican, the Uffizi Gallery, the British Museum, the Capitoline Museums and the museums of Naples, Turin and Munich, as well as the Imperial Hermitage. In particular, ancient Roman artefacts and the art of the Middle Ages in Western Europe were represented in the form of electrotype copies. To showcase the art of furniture making, a magnificent copy of Marie Antoinette's dresser from Garde-Meuble was ordered.

Krater. Late 19th century. Copy of an original from Hildesheim. Alexandria. Second half of 1st century BC

The year 1899 marked a momentous event in the history of the Stroganov School of Technical Drawing and even more so in the history of its museum: on May 6, the museum was named after Emperor Alexander II and became The Alexander II Museum of Decorative and Applied Arts. Donations followed; Fyodor Schechtel and Lev Kekushev, who both taught at the school at the time, donated a sum equivalent to their wages for the museum's needs.

Also in 1899, a well-known Moscow merchant, State Councillor Konstantin Popov gave the museum his substantial collection of Eastern art. Although the collection became the property of the Stroganov School of Drawing, the Emperor issued a decree officially naming it the K.S. Popov Museum. One of the best private collections in Russia, it was valuable and extensive and included decorative objects from China, Japan and Persia.

The Alexander II Museum of Decorative and Applied Arts was one of the few collections that were open to the public. By 1977, it housed more than 8,000 works of art.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Stroganov School of Technical Drawing went through several reorganisations: in 1918, it was known as the Free State Art Studios; in 1920, it merged into the Higher Art and Technical Studios (best known by its Russian acronym Vkhutemas), which, in 1920, became the Higher Art and Technical Institute (Vhutein), only to be divided in 1930 into a number of independent higher educational institutions. As a result, the Stroganov Museum's collection was distributed among several major national museums, including the Historical Museum, Tretyakov Gallery, Museum of Oriental Art, Museum of Ceramics, Ethnographic Museum of Soviet Nations, and Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts.

The Stroganov Museum ceased to exist. It was as late as 1945, when the Stroganov School of Drawing was reinstituted, that the decision was made to also bring back the museum. Some artefacts were returned from the previously mentioned museums and others came from various museum funds all over the country. Just as had happened in the 19th century, after the Second World War, the museum continued to receive donations. One example was the 1960 gift of a unique collection of Russian ceramics that had belonged to Alexei Filippov, an artist and art scholar who graduated from the Stroganov School of Drawing and went on to teach there. The collection included ceramic pieces by Mikhail Vrubel and Alexander Golovin, decorative ceramics made at the Abramtsevo workshops and by the Murava cooperative, exquisite examples of Russian porcelain, ceramic tiles, majolica and early Soviet porcelain designed in the 1920s and 1930s by Wassily Kandinsky, Vladimir Favorsky, Mikhail Lebedev, Pyotr Vychegzhanin and others.

When members of the Stroganov School of Design and Applied Arts Student Research Society went on expedition trips to old Russian towns in the 1950s and 1960s, they bought back wonderful works of folk art: spinning wheels, washing paddles, wooden chests, rubels (wooden instrument to smooth linens) and carved wooden window frames.

Today, the Stroganov Academy Museum houses more than 11,000 works of decorative and applied arts, sculptures, paintings and drawings, ranking among major museum collections, both in Russia and abroad.

The museum is especially proud of its unique collections of ancient art and Russian, Western European and Far Eastern porcelain and ceramics.

Ancient art is represented by artefacts from early Eastern Mediterranean cultures of the 2nd century BC, Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome up to the Late Roman Empire period. The collection is quite extensive and diverse and includes sculpture, small sculpture, terracotta figurines, ceramics and glass vessels.

The museum's collection of Ancient Greek and Italian vases is unique and includes all main types of vessels: amphorae, hydrias, kraters, alabasters, canthari, lekithoi, olpae, pelikes, kylikes and bowls. These vessels are decorated with paintings of every style - geometrical, Orientalised, black-figure, red-figure - and illustrate the work of large ceramic manufacturing centres at different times, such as Corinth, Attica, Boeotia, Tarentum, Campania and others, serving as a visual guide to the characteristic styles and places of manufacture.

As for the museum's collection of small sculptures, our Tanagra terracotta figurines dating back to the 4th and 3rd centuries BC and miniature clay satyr masks decorated with slip are worthy of a special mention. One figurine of a young Greek woman stands out: draped in gracefully folding clothing, she is a perfect and timeless example of the beautiful medium of small sculpture. As a whole, the museum has acquired a comprehensive collection of antique sculpture, which includes reliefs (fragments), decorative sculpture, sculptural portraits, represented both by the 19th-century casts and original works of the 4th century BC - to the 1st century AD.

The museum's Western European ceramics section is one of the most complete, featuring world- famous Meissen porcelain of the 18th and 19th centuries and items manufactured at the Vienna, Berlin, Ludwigsburg and Nymphenburg porcelain factories, as well as the so-called “small" manufacturers of Thuringia. The Sevres porcelain factory and private manufacturers of Paris are represented by strikingly beautiful individual pieces from the 18th and 19th centuries. The museum's permanent exhibition also includes Wedgwood Jasperware and basaltware, the manufacturer's famous creamware, as well as porcelain in the colonial style from other British manufacturers. Porcelain by the Danish Royal Manufactory in Copenhagen featuring underglaze painting with salts and expressive sculptural motifs reflects the technological innovations and aesthetic aspirations of the Art Nouveau style in ceramics at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Vase decorated with zodiac signs. England Wedgwood. 1800s

Jasperware

Eastern decorative art is mostly represented by exported Chinese and Japanese pieces from the 17th to 19th centuries: large and small Chinese vases, bowls and plates, drinking bowls, tureens with underglaze cobalt-blue painting and magnificent colourful enamel patterns in the style of famille rose and verte (pink and green). Japanese pieces include, first and foremost, vibrant Imari porcelain manufactured in the late 17th and early 18th centuries and the luxurious Satsuma pottery of the 19th century.

As for Russian porcelain of the 18th century, the museum houses items manufactured at the Imperial Porcelain Factory and the Gardner Factory. Examples of 19th-century porcelain from numerous private Russian manufacturers include those made by the workshops of Popov, Batenin, Markov, the Gulin and the Kornilov brothers, as well as the major "porcelain monopolist" Matvei Kuznetsov. The Stroganov Museum also holds a fairly extensive collection of Russian 17th to 19th century architectural and stove tiles made in Moscow, Yaroslavl, Kostroma, Veliky Ustyug and other locations.

Our collection also includes decorative ceramics from almost all former Soviet republics (now independent states), such as Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. This collection is an essential educational tool that creates a comprehensive picture of many national pottery-making traditions and their unique features.

Over the years, our museum has accumulated a notable selection of textiles - we have many examples of embroidery, needlework, lace, woven and printed fabrics from almost all periods and regions of the world, with the focus on Russian, Western European and Eastern silks and brocades from the 17th and 18th centuries. We also have a number of unique textiles, for example, Italian embroidery, silk and velvet dating back to the 16th century. Our collection of Russian woodblock-printed fabrics from the 18th and 19th centuries provides a good record of how traditional fabric manufacturing changed through the evolution of patterns and technology. In addition, the museum houses a great selection of Russian Orthodox Church vestments and ritual textiles - altar cloths, vestments, liturgical veils and Aȅrs - showcasing the rich variety of techniques and decorative materials, such as gold embroidery, lace, precious brocade and velvet fabrics.

The Stroganov Museum has also collected beautiful examples of metalwork, with some dating all the way back to antiquity. Along with some works from the 1st century BC, electrotype copies of famous works from Boscoreale, Pergamum and the Hildesheim Treasure are on display. The art of Medieval Europe is represented mostly by electrotype copies of artefacts from major French and German museums - the Stroganov Museum commissioned these copies in late 19th century. These works are mostly ritual objects created by the master craftsmen of Limoges: 12th-century tabernacles, pastoral staff knobs, reliquaries and Gospel treasure bindings. All of these pieces are decorated with continuous ornamental patterns of champleve enamel. Painted enamels by Limoges master craftsmen such as Jacques P. Laudin (1603-1629) illustrate an interesting point in the evolution of Renaissance decorative metalwork: the tendency for enamel art to draw closer to painting.

Our collection of Russian decorative metalwork of the 17th-20th centuries is probably the most comprehensive one. It includes such typical Russian tableware of the 17th-18th centuries as copper and tin wine cups and bowls - stopas, bratinas, charkas, yendovas - decorated with engravings and hammered ornamental patterns. Unique Russian enamels made in Veliky Ustyug in the 18th-19th centuries stand out due to their outstanding quality of craftsmanship. The museum also housed remarkable works manufactured in the Urals and Siberia, dating back to the first half of the 18th century.

A special place in this collection belongs to religious objects: patens, liturgical dishes and plates, chalices, folding altars, wedding crowns and tsatas (part of icon decorations) made from hammered and filigree silver, tin, copper and brass and decorated in various techniques, such as cloisonne enamel on a scan (Russian tradition of filigree), as well as painted and openwork enamel. All these pieces are masterfully executed in vibrant colour and exquisitely decorated. Also well worth mentioning is our extensive collection of baptismal crosses and wearable icons (12th-19th centuries), cast in copper and sometimes decorated with enamel. Our collection of decorative metal objects allows the visitor to visualise the evolution of artistic styles and the variety of metal-working techniques in different cultures.

The Stroganov Museum's furniture collection includes examples of almost all styles and periods, beginning with the Renaissance. Along with original works, the museum houses copies of the best pieces created by Russian, Western European and Asian furniture makers, which helps fill the gaps in the collection and showcase the main stages in the development of this craft. Most of these copies were commissioned from European museums at the end of the 19th century, and include some French furniture by Jean-Henry Riesener and Guillaume Beneman. As for the originals, the museum houses some unique 17th-century German, 18th-century Italian and 19th-century Russian furniture; there are two remarkable cabinets by the French cabinetmaker Mathieu Befort Jeune, whose attribution was confirmed in 2008 during restoration by the Academy's experts at its Department of Furniture Restoration. Another extraordinary piece is the tower cabinet with four chairs in the Russian Revival style; manufactured in 1903 at the Imperial Stroganov School workshop, it is decorated with stylised papier-mache ornaments and brass overlays.

The museum also houses some Asian furniture, including traditional Chinese and Korean pieces, as well as a 19th-century Japanese cabinet decorated with carvings and porcelain inserts with battle scenes.

Russian folk woodcarvings represent a large part of this section: carved wooden friezes from the 18th-19th centuries in the so-called “riverboat" style; carved exterior house decorations, such as window casings, cornices (primarily 19th century); spinning wheels, washing paddles, rubels and other household objects - kovshi and skobkars (traditional drinking vessels), salt cellars and cradles (mostly from the 19th century), decorated with characteristically vibrant and sumptuous traditional folk ornamental patterns (17th-18th centuries).

Images carved in wooden blocks used for printing fabric and making gingerbread offer a perfect opportunity to study the folk carving tradition and its sculptural expressiveness - starting with the 17th century, these patterns were so popular that they continued to be copied and used until the late 19th century. Our collection of chests and decorative boxes (made in Veliky Ustyug in the 17th and 18th centuries, they are bound in intricate cast iron and decorated with multi-coloured mica and paper) is also unique.

As for paintings and drawings, our museum houses works executed mostly in the 17th-21st centuries in a range of graphic techniques (engraving, pencil and pen drawing, watercolour, gouache), as well as paintings, such as monumental frescoes, temperas and lacquer miniatures.

Our visitors can see fragments of original 17th- century Russian frescoes; first-class copies of the Italian Renaissance paintings, both monumental and easel examples; miniature lacquer paintings from China and Japan (19th and 20th centuries). We have a unique collection of drawings and sketches by renowned Russian artists and architects of the early 20th century, including works by Mikhail Vrubel, Stanislaw Noakowski, Sergei Yaguzhinsky, and Fyodor Schechtel. The museum has also accumulated a significant number of graphic sheets executed by the school's students in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These works are valuable because they reflect the learning standards and requirements at the Stroganov School at different stages of its history and allow us to trace the evolution of applied-arts education in Russia.

There are some smaller collections at the museum, which cover such subjects as ethnography and archeology, stone sculpture and plaster casts, and artefacts made from a variety of materials, numbering close to 400 items in total.

Our museum treasures all artefacts that are related to the history of the Stroganov School, be it archival documents, photographs of workshops and their products, students' drawings (they include first class sketches and compositions) or other works in a range of media, executed in the early 20th century. These works are an integral part of our collection as it relates to the school's history; they reveal our students' distinct creative style and clearly illustrate the Stroganov School's educational standards and practices, with its original commitment to “cultivate the students' creativity and refined artistic taste."

Additionally, our displays include the works of the school's distinguished educators of the present day (late 20th - early 21st centuries), as well as the best graduation and course projects of recent years.

Students during class at the Stroganov Academy of Design and Applied Arts Museum

Modern photograph

Currently, our museum's collection serves as a base for training and research work by the school's undergraduate and graduate students and educators. On the whole, the goal of the Stroganov Academy Museum is to preserve and enrich the celebrated heritage of Russia's oldest educational institution.

- A. Hartwig. School of drawing for decorative and applied arts, established in 1825 by Count S.G. Stroganov: its origin and expansion up to 1860. Compiled by A. Hartwig. Moscow, 1901. P. 133.

- Moskvich. Stroganov Central School for Technical Drawing in Moscow // The Arts and Manufacturing of Decorative Objects. Moscow, 1899. Issue 5. P. 288.

Porcelain. Overglaze polychrome painting

Photograph

Terracotta, lacquer, painting

Photograph

Gift of Emperor Alexander II to the Stroganov School Museum. St. Petersburg, Russia Imperial Porcelain Factory. 1855-1881

Porcelain, overglaze polychrome painting, gold plate

Photograph

Carved oak, gilding

Plaster copy. 19th century

Clay, engobe, lightblue and pink paint. Greece. 4th-3rd century BC

Porcelain, overglaze polychrome painting, gold plate

Moscow, Russia. Abramtsevo decorative ceramics workshop. Circa 1900

Majolica, metallic glaze

Porcelain, decorated with underglaze cobalt painting, overglaze red painting and gilding

Porcelain, overglaze polychrome painting, gold plate

Copper, enamel, painting

Copper and painted enamel

Cast pewter

Copper with stamped silver overlays on white enamel

Cast copper, painted enamel, repoussé decoration

Copper, cloisonné enamel

Handwoven with gold threads and chenille

Velvet embroidered with gold thread

Braids, silk, pearl beads, tinted glass

Walnut, ivory, inlay, veneer

Walnut, pewter, ivory, inlay, veneer, carving

Birch and oak wood, bronze, cabinetry, veneer, tinting

Carved oak

Paris, France. Original by master cabinetmaker Guillaume Beneman, executed in 1787 for the Château de Compiègne Council. Room. Mahogany, bronze, marble, polish, cast metal, gilding

Clock. Workshop of Pierre-Philippe Thomire. Paris, France. Early 19th century

Clock in the style of Louis XVI. Paris, France. 18th century. Marble, bronze, enamel, patination, gilding

Candelabra. Paris, France. Workshop of Pierre-Philippe Thomire. Early 19th century

Tempera on canvas. Early 20th century

Oil on canvas

Oil on canvas

![Jug decorated with Rocaille patterns, stamped “ИМФ 1762 г. Сибирь” [Siberia]](https://www.tg-m.ru/img/mag/2020/2/art_67_02_24_1.jpg)