The Met at 150. RUSSIAN ART IN THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART’S THOMAS J. WATSON LIBRARY

The Thomas J. Watson Library, the primary research library of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, holds more than one million volumes on art, archaeology, architecture, ornament and design. Founded in 1870 under the same charter as that of the Museum itself, the scope of the Library collection is as encyclopaedic as the Museum’s. Offering a strong complement to Russian art and objects in the Museum’s curatorial collections, Watson’s holdings promote awareness, understanding and appreciation of an even wider field of Russian art and material culture.

Reading room of the Metropolitan Museum of Art Library,

designed by McKim, Mead, and White, 1920

Watson’s collection of Russian journals, catalogues and other monographs on art and antiquities is one of the largest and most expansive publicly accessible research collections outside of Russia. The Library serves as a critical centre for visitors studying Russian art of all periods, movements, styles and mediums, as well as Russian- language readers researching non-Russian subjects (via publications and catalogues from major Russian institutions on non-specifically Russian themes).

In the present essay, I examine the Met Library's origins and history of collecting Russian art documentation, highlighting transformative moments and exceptional acquisitions from the past 150 years as well as recent developments and initiatives that attest to Watson's commitment to remaining a vital centre of support for Russian art research, open to all.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art was formally established on April 13, 1870, through an act of incorporation by the legislature of the State of New York. The act authorised the Museum's founders to establish and maintain not solely a museum, but “a museum and library of art" for the purposes of “encouraging and developing the study of the fine arts, and the application of arts to manufacture and practical life, of advancing the general knowledge of kindred subjects, and, to that end, of furnishing popular instruction and recreation."[1]

In 1880, after a decade of hosting exhibitions in rented spaces, the Museum opened a newly constructed, permanent building in Central Park, in the same location where it stands today. A “small, dark, damp room in the basement"[2] was designated as a storeroom for the approximately 200 books, pamphlets, and other publications that had accumulated over the museum's first ten years. The Library relocated to an above-ground location within the Museum in 1888 - still a single room, but with more hospitable conditions - and, in 1910, moved into an annexe to the Museum built specifically for the Library.

At the time of its opening, the Museum's permanent art collection was not much more distinguished than the Library's. Museum officials had high aspirations and intentions and they recognised that a strong research library was essential for informed, responsible collection building. In a 1906 report to the Museum trustees, Sir Casper Purden Clarke, the Museum's director at the time, stated: “In the building up of the collections of the Metropolitan Museum, the great work has to be done in a few years, and books will be amongst the most important tools used by us in achieving the result. I, therefore, propose that in dealing with the Library, the [Executive] Committee should place no restriction upon the quantity of books purchased, or the space necessary to properly house them."[3]

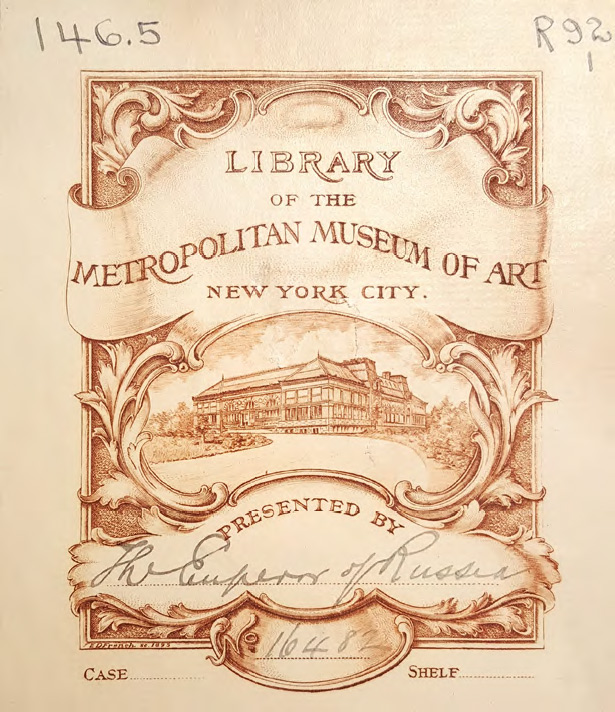

Donor bookplate inside the front cover of An Inventory of the Silver in the Court of His Imperial Majesty

acknowledging that it was “Presented by The Emperor of Russia”. Bookplate designed by Edwin Davis French, 1895

The core of the Library's collection from its earliest years has been the documentation of art and visual and material culture from antiquity to the present day, from all parts of the world. From the outset, the Library was intended to be a resource for not only museum staff and curators, but the public at large. To that end, the Library's reading room saw constant, heavy use by museum administrators and curators, as well as outside art historians, art history students, artists and designers. Industrial-arts and fine-arts classes used the library's print holdings and photographic study collection as source material for study, tracing and inspiration.

In the library's first few decades of existence, the collection grew slowly and modestly. With limited funds to purchase books and serials, the library's principal source for acquisitions was gifts and donations from Museum trustees, administrators and benefactors such as Samuel P. Avery, Luigi Palma di Cesnola and Edward C. Moore. The focus of the earliest library acquisitions closely paralleled the primary exhibition interests and collecting aspirations of the Museum staff: archaeology, antiquity, medieval art, arms and armour, decorative arts, painting, sculpture, textiles and costume.

At the start of 1905, after 25 years of active collecting, the total number of volumes in the Library's collect i on numbered 8,593; of that number, approximately ten titles were from Russia. (Only one title was in the Russian language; the others were in French or German.) Five of the ten titles came to the library in 1892 as gifts from Moore. A silversmith who served as the jewellery design director and head of the silver workshops at Tiffany & Co. from 1851 to 1891, Moore amassed a collection of 2,000 extraordinary objects from around the world to serve as sources of inspiration. Upon his death, he left the collection to the Museum and 460 books to the Library[4].

Moore's gift included one of the most monumental, extravagant art publications of the 19th century: Fedor Solntsev's “Antiquities of the Russian State", published by Imperial Command of Sovereign Emperor Nicholas I[5]. Financed by Nicholas I, “Antiquities" presents more than 500 chromolithographs bound in six folio-sized volumes, that reproduce renderings by Solntsev of medieval artifacts in Imperial collections in Moscow. The publication presents an extraordinary collection of religious objects, vestments, regalia, arms and armour, clothing, household implements and architectural ornament, all in exquisite detail.

Fedor SOLNTSEV. Antiquities of the Russian State Moscow, 1849-1853

Prominent private Russian collectors also donated publications to the Met Library. In 1889, Nikolai Mikhailovich Postnikov, a Moscow dealer and collector recognized for having assembled “the largest of all the nineteenth-century state and private collections" of icons[6], donated a catalogue of his collection[7]. Princess Maria Tenisheva gave the library a copy of “Talachkino: l'art décoratif des ateliers de la princesse Ténichef" (St. Pétersbourg: Édition Sodrougestvo, 1906), and Princess V.P. Sidamon Eristoff donated a copy of a collection catalogue of antique Russian embroidery and lace: “Sobranīe russkoĭ stariny Kn. V.P. Sidamon-Ėristovoĭ i N.P. Shabelskoĭ: vypusk I-ĭ, vyshivki i kruzheva” (“Antiquités russes, collection princesse Sidamon-Eristoff et Mlle. N. de Schabelskoi" (Moscow, 1910).

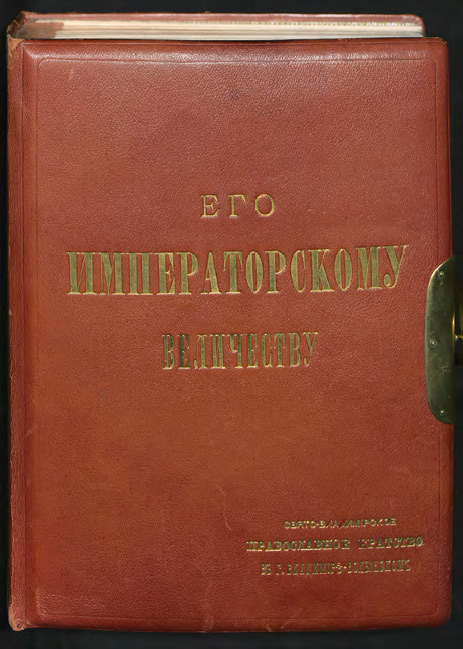

Library reports in the “Museum Bulletin" in 1907 and 1908 acknowledge receiving catalogues of Russian Imperial collections as gifts from “The Emperor of Russia, through the Ministry of the Imperial Court": “Die Vasen-Sammlung der Kaiserlichen Ermitage (St. Petersburg, 1869) and “Opisi serebra dvora Ego Imperatorsk- ago Velichestva (Inventaire de l'argenterie conservee dans les garde-meubles des palais imperiaux): Palais d'Hiver, Palais Anitchkov et Château de Gatchino", edited by Baron Armin von Foelkersam (St. Petersburg: T-vo R. Golike i A. Vilborg, 1907). A bookplate honouring the donor, Nicholas II, attests to the gift.

In addition to collectors, Russian artists and their estates have contributed significantly to the Library's collection and continue to do so today. Five books illustrated with silhouettes by popular 19th century artist Elizaveta Bem were donated posthumously by a relative of the artist. Russian and Ukrainian artists who resettled in the United States, such as Alexander Archipenko and Abraham Walkowitz, also donated catalogues and photographs of their work for the library's photographic study collection.

By 1915, the Library's collection had grown from 8,593 volumes, in 1905, to 34,873, and the number of Russian holdings had increased from approximately 10 to 65. The dramatic increase in overall acquisitions between 1905 and 1915 was made possible primarily thanks to a museum benefactor, Jacob S. Rogers, who, upon his death in 1901, left $5 million from the liquidation of his estate to the Museum. Rogers's will stipulated very specifically that the funds were to be used to establish an endowment, the principal sum of which could not be diminished, and the interest from which could be used for “the purchase of rare and desirable art objects, and in the purchase of books for the Library of said Museum, and for such purposes exclusively."[8]

Within the first ten years of the Rogers Fund, the library was able to acquire a remarkable number of what are now widely regarded as crowning examples of Russian printing and art-book production: “History and Monuments of Byzantine Enamels" (Frankfurt, 1892), a catalogue highlighting 43 early Byzantine, Georgian and Kievan enamels from the collection of Aaron Zwenigorodskoi[9], with text by Nikodim Pavlovich Kondakov; “Drevnosti Bosfora kimmeriiskago, khraniashchiiasia v imperatorskom muzeie Ermitazha" (St. Petersburg, 1854); “Tsarskoselskii arsenal, ili, sobranie oruzhiia" (St. Petersburg, 1869); and the four-volume opus, “History of the Russian Hunt from the Tenth through Nineteenth Centuries" by Nikolai Kutepov, which features commissioned illustrations by an all-star roster of artists, including Be- nois, Lansere, L. Pasternak, Repin and Viktor Vasnetsov among others (St. Peterburg, 1896-1911).

The Rogers Fund enabled the Library to initiate subscriptions for current Russian art and architecture journals such as “Starye gody" (Petrograd, 1907-1916) and “Apollon" (Petrograd/St. Petersburg, 1909-1917). From antiquarian booksellers, the Library acquired older issues of these and other periodicals, such as “Viestnik iziashchnykh iskusstv" (St. Peterburg, 1883-1890), and text and atlas volumes of the archaeological periodical “Compte Rendu de la Commission Imperiale Archeologique". Thousands, if not tens of thousands, of titles have been purchased by the Library through the Rogers Fund since 1904, and the fund remains one of the principal sources for new library acquisitions, including Russian titles, to date.

From 1925 to 1929, annual Russian acquisitions by the library began to rise dramatically: it added more Russian titles in those five years than in its first 55 years combined, bringing the total number of Russian holdings from approximately 95 at the end of 1924 to 225 by 1930. Although the Met continued to buy retrospective, out- of-print material whenever offered, it also began acquiring newly published, contemporary Russian material in greater volume, from sources in Germany and the United States.

In addition to new publications from Moscow and Petersburg, the Library purchased a significant volume of books published in Berlin, the main centre of Russian- language publishing in the early 1920s. The publishing house Petropolis is particularly well represented in the collection, through catalogues and books illustrated by Russian modernist artists such as Boris Grigoriev, Mstislav Dobuzhinskii and Nathan Altman. Library purchases reveal a sustained interest well into the 1930s in contemporary Russian and Ukrainian artists working in illustration and graphic design (Alexandre Jacovleff, Pavel Kuznetsov, Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva and Sergei Chekhonin, among others); theatre and costume design (Lev Bakst and Anatoli Petrytskyi); and Russian modern and avant-garde art in general.

The spike in Russian-language acquisitions beginning in 1925 also coincides with the emergence of a number of Russian-language booksellers in New York City, dealing extensively in new and antiquarian art publications and illustrated books.[10] The Library's Russian holdings increased even more dramatically in the 1930s through gifts from Soviet cultural agencies and direct publication exchanges with museums such as the Tretyakov Gallery, the State Museum of Modern Western Art, the Hermitage and the Georgian State Museum, among others.

Considerable scholarship has been devoted to the history of book sales by Soviet authorities from Imperial library collections to American institutions, often via intermediary booksellers in the 1930s and 1940s. Like other institutional collectors at the time, the Met purchased Russian material from the New York-based booksellers who figure most prominently in these histories: Simeon Bolan, Katerina Nikanorovna Rosen and H.P. Kraus. In comparison to other institutions such as the Library of Congress, New York Public Library, and Harvard University that were acquiring thousands of volumes “en bloc", the volume of book acquisitions by the Met was extremely modest.

Album of photographs from the archaeological trip made by Professor A.V. Prakhov in Volyn in 1886. Kiev, 1889

Front cover and interior illustration

In the early 1940s, Bolan and Rosen were two of the Met's primary sources for general, less precious Russian art catalogues and monographs on pre-Revolutionary and Soviet art, artists and artist organisations. From H.P. Kraus, the Library purchased rare, often elaborate, collection catalogues, major reference works and photographic albums of Russian architecture antiquities, and archaeological expeditions. Since 2008, an initiative by the Library to make the most rare and unique Russian items in its collection available online has led to most of these titles being scanned and posted on the Library's Digital Collections web portal, for free viewing and download.[11] There, one can access catalogues such as “OpisanTe kollektsii narodnykh pisanok"[12], a richly illustrated catalogue of more than 2,100 pysanky in the collection of Lubenskī ĭ muzeĭ E.N. Skarzhinskoĭ, and “Al'bom fotograf ī ĭ k arkheologicheskoĭ poiezdkie professora A.B. Prakhova na Volyn' v 1886 godu", a photographic album of antiquities recorded by Adrian Prakhov on an expedition to Volyn in 1886.[13] Four titles purchased in the 1940s by the Library bear traces of Russian Imperial ownership: three contain ink stamps or bookplates of Alexander III, including this Prakhov album, and one bears the stamp of “Tsarskosel'skaia dvortsovaia biblioteka’’.

Album of photographs from the archaeological trip made by Professor A.V. Prakhov in Volyn in 1886

Kiev, 1889. Detail of title page

By the end of the 1950s, the Library had managed to acquire many of the most essential reference works on Russian art published in the 19th and early- 20th centuries. In 1973, the Humanities Fund helped the Library fill in several critical titles that had eluded it with donations of books from the collection of Boris Bakhmeteff. Particularly noteworthy among the gifts is the exceptionally rare and significant 12-volume collection by Dmitrii Rovinskii, “Materials for Russian Iconography" (“Materialy dlia russkoi ikonografii") (St. Petersburg: Ekspeditsiia zagotovleniia gosudarstvennykh bumag, 1884-1891).[14]

In the 21st century, Watson Library has emerged as one of the largest and most expansive publicly accessible research collections on Russian art and design outside of Russia. Assistance and support from booksellers, gallerists, curators, librarians and museum colleagues throughout Russia and the FSU allows it to ensure that not only prominent Russian artists and institutions are represented in the collection, but smaller, independent galleries, collections, and publishers are as well, from major cities and beyond. In addition to art catalogues, monographs and periodicals, the Library is adding increasing numbers of contemporary Russian photobooks, artists' books and other artist-published editions.

Individual donors continue to play a critical role in building the Library's collection. Between 2014 and 2016, Charlotte Douglas, an American art historian most widely known for her scholarship on Kazimir Malevich and the Russian avant-garde, gave more than 1,000 print titles from her library that were not already held by Watson and three major microfiche collections. Charlotte's library, assembled over the span of more than 50 years, substantially expanded Watson's coverage of the avant-garde (especially Malevich and Russian women artists), as well as Russian painting of all periods, including modern and contemporary art from the 1970s to 2000. Many of Charlotte's books bear warm dedications to her by the authors or artists represented therein, including Dmitrii Sarabianov, Georgii Kovenchuk, Mai Miturich, and Francisco Infante.

Funds provided by the Library's patron group, The Friends of Thomas J. Watson Library, allow Watson to continue to purchase critical, out-of-print research titles that may have been overlooked or that were not easily obtainable when first issued, as well as more recent limited editions. Recent acquisitions made possible by support from the Friends group include the journal “Iskusstvo i khudozhestvennaia promyshlennost’’ (Art et industrie = Kunst und Gewerbe = Sztuka i przemysl = Művészet és ipar) (St. Petersburg: Imperatorskoe ob- shchestvo pooshchreniia khudozhestv, 1898-1902); avant-garde publications of the 1910s to the 1930s; Ballets Russes programmes; a complete set of the serial publication “WAM" (“World Art Muzei’’), published by Agey Tomesh and Arsenii Meshcheriakov from 2002 to 2008; and publications by Mikhail Karasik and artists of the Mitki art collective. Friends funds also supported the purchase of nearly 1,000 exhibition catalogues and monographs from all regions of the former Soviet Union from the collection of Viktor Kholodkov, a dealer and collector who emigrated from Russia to the United States in 1989.

The Imperial Porcelain Factory. Easter Eggs. St. Petersburg. Private Collection

Moscow: GRANY Foundation, 2017

Today, Watson holdings include more than 14,000 Russian language titles and 5,000 additional titles on Russian art, artists and material culture in English and other Western languages. Approximately 8,500 of those 14,000 have been acquired since 2010. As the Met Library steps into the next 150 years, it looks forward to serving as an even greater pillar of support for curators, historians, artists and members of the general public seeking a deeper awareness and understanding of Russian art and material culture.

- Charter of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, State of New York, Laws of 1870, Chapter 197, passed April 13, 1870 and amended L. 1898, ch. 34; L. 1908, ch. 219.

- Howe, Winifred E. A History of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; with a Chapter on the Early Institutions of Art in New York. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1913. p.304.

- As cited in “The Scope of the Library.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Library, 1905. Occasional Notes, no. 1. Supplement to the Bulletin for March, 1906. New York. p.5.

- An exhibition featuring more than 180 extraordinary examples from Moore's bequest, alongside 70 silver objects designed at Tiffany & Co. under his direction, will take place in conjunction with the 150th anniversary of The Met: “Collecting Inspiration: Edward C. Moore at Tiffany & Co.” will run from July 13 to October 4, 2020, in the Met Fifth Avenue.

- Solntsev, Fedor. “Drevnosti rossiiskago gosudarstva, izdannye po Vysochaishemu poveleniiu Imperatora Nikolaia I”. Moscow: Tipografiia A. Semena, 1849-1853.

- Vzdornov, Gerold I. “The History of the Discovery and Study of Russian Medieval Painting” (Boston: Brill, 2017), p.302; translation of “Otkrytie i izuchenie russkoi srednevekovoi zhivopisi” (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1986).

- “Katalog khristlanskikh drevnosteT sobrannykh moskovskim kuptsom Nikolaem MikhaTlovichem Postnikovym” (Moscow: Tipo.-lit. I.N. Kushnereva, 1888).

- “Report of the Trustees for the Year. 1901.” Annual Report of the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 32, 1902, pp.18-19.

- Published in an edition of 200 copies, “History and Monuments” was published in German as “Geschichte und Denkmaler des byzantinischen Emails”, in French as “Histoire et monuments des emaux byzantins”, and in Russian as “Istoriia i pamiatniki Vizantiiskoi email”. The Library purchased a German copy in 1907, and received a French copy as a gift in 1944. This publication and the Zwenigorodskoi enamels collection have special significance for the Met: the collection ultimately was purchased by J.P. Morgan and given to the Met in 1917.

- A significant number of books in the Met’s collection purchased during this period bear labels or other notations of one firm in particular: Central Book Trading, a Russian-language bookstore and publisher that officially began operating in Greenwich Village in 1925.

- “Rare Books Published in Imperial and Early Soviet Russia.” Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections.

- KulzhinskTT, S.K., sost. “OpisanTe kollektsii narodnykh pisanok”. Moskva: Postavshchik VysochaTshago dvora T-vo skorope- chatni A.A. Levenson, 1899. Full text available via TJWL Digital Collections.

- Prakhov, A.P. “Albom fotografTT k arkheologicheskoT poiezdkie professora A.B. Prakhova na Volyn v 1886 godu”. Kiev, 1889. Full text available via TJWL Digital Collections.

- Rovinskii’s other magnum opus, “Russkiia narodnyia kartinki” (St. Petersburg, 1881), was purchased by the Museum through another endowed acquisition fund: the Harris Brisbane Dick Fund.

Moscow: printed by A.A. Levenson, 1899

а collection of Central-Asian ornamentation, recorded by N.E. Simakov. St. Petersburg, 1883

St. Petersburg, 1869

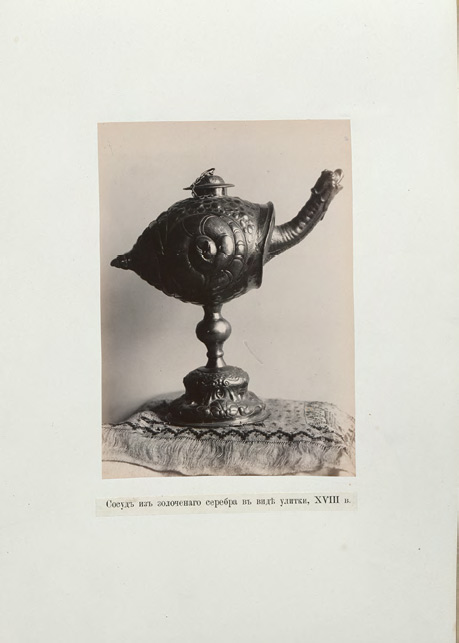

Illustration from: “A Historical Account of the Museum of Russian Antiquity, known as the Workshop and Armory Chamber located in Moscow”. Moscow, 1807

Illustration from: “A Historical Account of the Museum of Russian Antiquity, known as the Workshop and Armory Chamber located in Moscow”. Moscow, 1807

Saint Petersburg: Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, 1898–1902

Text by V. Khmuryĭ. [Kharkov]: State Publishing House of Ukraine. 1929

Imprint: annual almanac of printed graphic art “Ot’tisk”. St. Petersburg, 2001-2005