A Premonition of the Future. THE GRAPHIC WORKS OF VASILY CHEKRYGIN FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE TRETYAKOV GALLERY

“The subject of my art is the human spirit...”[1]

Vasily Chekrygin

The 120th anniversary of the birth of Vasily Chekrygin (1897-1922), the painter and graphic artist whose work many influential critics have called unique in the visual arts of the 1910s-1920s, fell on January 19 2017 Timed to coincide with that anniversary and organized as part of the project “The Tretyakov Gallery Opens Its Reserve Collections”, the show introduced the public to the Tretyakov’s collection of Chekrygin’s graphic works.

The history of the creation of the Chekrygin collection is linked to the acclaimed art scholar and museum professional Anatoly Bakushinsky. In one of his articles about Chekrygin's art, Bakushinsky wrote: “The extraordinary sweep of the creative daring, the inexhaustible wealth of imagination, the visionary approach to creative ideas, the monumentality of forms, so rarely seen in modern art, produce on the viewer a strange impression. All this distinguishes Chekrygin's art from that of his contemporaries, while also firmly anchoring it in the true and deeply tragic visage of modern times."[2]

In 1923, Bakushinsky organized Chekrygin's posthumous exhibition at the Tsvetkov Gallery, and brokered an arrangement between the Tretyakov Gallery and Chekrygin's widow resulting in the acquisition of 30 eminent works by the artist. Nearly all of those featured prominently in the new exhibition, along with others donated to the Gallery in 1969 by Alexei Sidorov, the prominent scholar of graphic art, and by the famous collector of the Russian avant-garde George Costakis in 1977. The Tretyakov collection of Chekrygin's graphics, today the equal of that held in any museum, comprises more than 400 works, most of which were acquired in the 1970s-1980s from his family.

The show featured 64 works attesting to the artist's fantastic talents and the grandeur of his formidable ideas, many of which were never realized. Many of the pieces on view were created by Chekrygin during the last three years of his life, which he himself described as a period of “frenzied" drawing. At that time the artist worked with tremendous creative enthusiasm on graphic sketches for his future frescoes “Existence" (1920-21) and “Restoring the Dead to Life" (1921-22). As if sensing that he would soon die, he produced more than 1,400 graphic pieces in a short period.[3]

The earlier stage of Chekrugin's creative activity, when he was influenced by Larionov's Rayonism, was highlighted at the exhibition by the multi-figure compositions he created in the 1910s. The artist produced fascinating semi-abstract images using the expressive power of light and darkness. In these compositions the human figures, as if in the process of “transformation", melt into streams of light, which in these pieces structures the space and lends to the images a special radiance and spirituality (“Spring").

At that time Chekrygin was known in Moscow circles as a participant in the futurist exhibitions and other such provocative shows.[4] Then very young and sensitive to everything new, the artist fell under the sway of the idea that traditional artistic values were unimportant: such a point of view was preached and practiced by his fellow students at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, Vladimir Mayakovsky and David Burliuk. With his characteristic fearlessness he focused on pure experimentation and soon became a prominent figure of the avant-garde. Chekrygin's works were presented at the so-called “Exhibition No. 4", organized by Larionov and featuring Futurists, Rayonists and primitivists, and received favourable reviews from several Moscow critics. Such experimentation with forms, however, was just “a first step" for the artist, a move in search of his direction in art, and unlike many avant-garde artists he never scorned the achievements of classical art; the spiritual component of the image had always been of crucial importance to him. Thus, the artist's friend and fellow student at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture Lev Schechtel (Zhegin) reminisced that Chekrygin was always "talking about the Spirit, spirituality, Christ."[5]

His illustrations to Mayakovsky's first collection of futurist poems “I!" are a case in point. For this unique work, published in 1913, which proved a real gem of the Tretyakov Gallery exhibition, Chekrygin designed fonts that emulated Old Slavonic script and biblically themed illustrations.[6] Zhegin wrote that the poet felt confused by the artist's work, because it was did not accord with futuristic aesthetics: “Well, Vasya," Mayakovsky grumbled, “once again you've come up with an angel - you'd better paint a fly, it has been a long time since you last did!".[7] Remarkably, Chekrygin soon lost interest in abstract forms and with his characteristic fervour started a bitter dispute with the Suprematists and Constructivists, as he defended the achievements of classical art. According to the accounts of the artist's contemporaries, the panache and uncompromising stance which distinguished the “frantic" Chekrygin's pronouncements about art, to which he was fanatically dedicated, left no one indifferent.

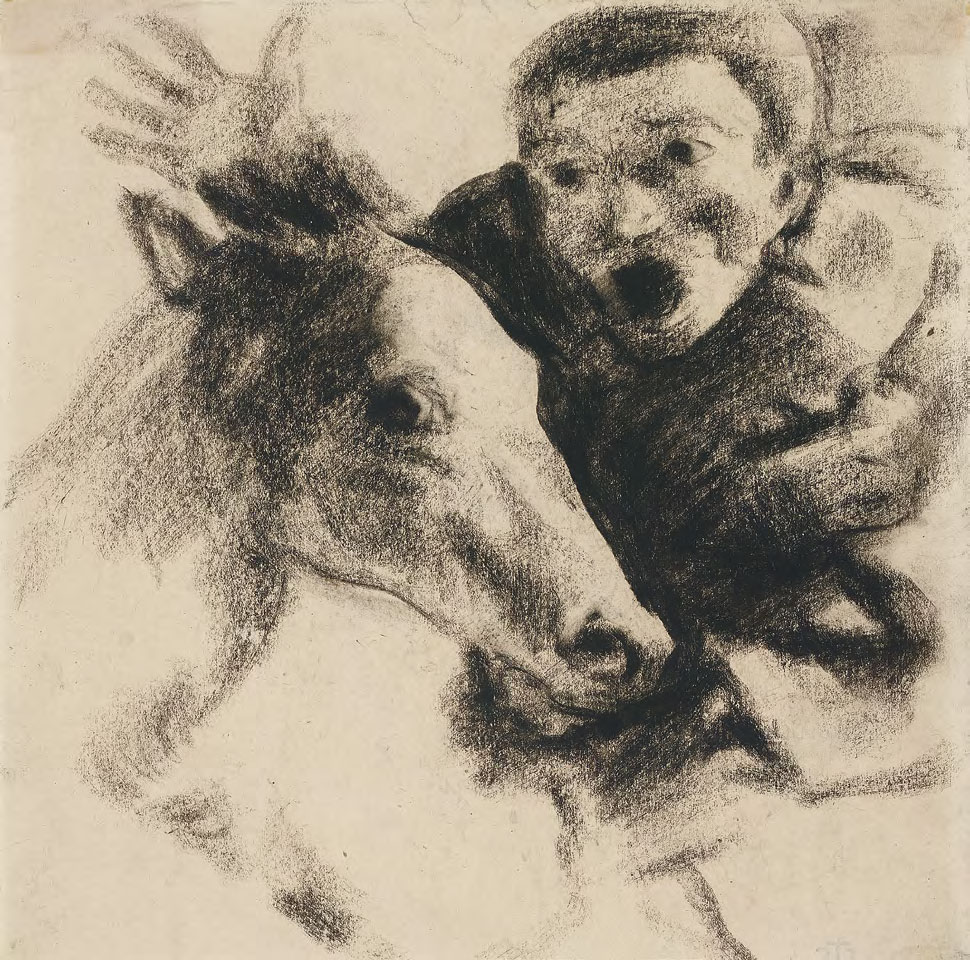

Chekrygin's formative years as an artist coincided with the period of the revolution and the civil war. He witnessed brutal fratricidal warfare, starvation, cold, destruction and terror. In his graphic series “Uprising" and “Faces", Chekrygin powerfully and expressively presented the terrible realities of the world that surrounded him. Using the materials that were the easiest to find at that difficult time - paper and compressed charcoal - he hurriedly captured on paper the symbolic images that came to his mind. Works such as “Execution by Shooting", “Screaming Woman", “Crying Woman" and “Heads of a Slave and a Horse" were produced at the height of his creative inspiration. The contrasts of tones of light and dark and the rhythmic quality of the black and white spots highlight the inner tension of the images, lending them a profound meaning and demonstrating a tragic vision of the revolutionary events. It would be not unreasonable to argue that these images, monumental in form and emotionally charged, were produced by Chekrygin as he was preparing for the fresco titled “Existence", a project that he had begun to consider in mid-1920. The artist's surviving notes show that he planned a composition consisting of three series of images on historical and contemporary themes.[8] In addition, in the multi-figure compositions and their individual details some sort of overarching plan for the composition can be traced, which justified presenting these pieces as a single group at the show. This general “existential" imagery was complemented by gripping pieces from the “Orgies" and “Crazy People" series, as well as his portrait sketches.

Heads of a Slave and a Horse. 1920

Compressed charcoal on paper. 23.5 × 22.5 cm

However, Chekrygin soon became absorbed in another, truly fantastic subject. At the end of 1920 the artist, after reading the works of Nikolai Fedorov, the religious thinker who was one of the pioneers of Russian cosmism, became a devoted follower of his teaching.[9] The philosopher viewed nature as a force that not only gave birth but also one that brought death: thus, he advised learning to control the natural environment in order to overcome starvation, illnesses and, finally, death itself. The triumph over death, and bringing back to life all the dead who had ever lived and resettling them on other planets should become, according to Fedorov, “common cause" for the inhabitants of Earth.

The philosopher did not consider that his idea of establishing a new world, and creating an immortal and transformed individual was utopian. As he saw it, this ambitious goal could be achieved through a synthesis of theory and applied science, art and religion, as well as the fraternal unity of all “sons of man". He wrote: “Through rational beings, nature achieves a full knowledge of self and full self-government, reproduces all things that have been destroyed and are being destroyed on account of its still existing blindness."[10] Admirers of Fedorov, both as an individual and as a philosopher, included Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, Nikolai Berdyaev, Vladimir Solovyov, Vyacheslav Ivanov, Valery Bryusov and Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Berdyaev wrote that the originality and power of Fedorov's philosophy consisted “in his extraordinary, singular awareness of the human being's active mission in the world, in his religious demand to approach nature actively, regulating and transforming it".[11]

Chekrygin was deeply impressed by the philosopher's ideas about regulating natural processes and populating the universe with human beings. “I'm reading Nikolai Fedorov, a Moscow philosopher," he wrote. “His thoughts are similar to mine... The dead brought back to life - not the Resurrection. We, sons of dead fathers, are the doers, bringing them back. It's not passive expectation of the miracle of Resurrection. The fathers raised from the dead will settle on the stars, whose movement is to be regulated by the collective will of all the living."[12] Following in Fedorov's footsteps, the artist became acutely aware of the phenomenon of death as the key problem of human existence, conceiving an unprecedented idea to create a monumental mural on the theme of “Restoring the Dead to Life". In five sketches that he made in 1921, which were probably intended as the compositional centre of the fresco's middle tier, the artist created an impressive picture of universal salvation. Conveying through visual means the philosopher's idea of bringing all people back to life, not only the righteous ones, Chekrygin pictured all the figures in a flurry of activity: either already rising, or in the process of freeing themselves from the captivity of death. Masterfully using the techniques of graphic art - line, spot, and contrasting tones of light and dark - the artist attained an imagery that matched Fedorov's vision of the resurrection, according to which scientists would use the radial energy sparked by vibrating molecules.

Multi-figure Composition with a Sphere. 1921-1922

From the series “Restoring the Dead to Life” (1921-1922). Compressed charcoal on paper. 39 × 31.2 cm

According to Fedorov, the light from molecules would be of crucial importance, so the artist also focused on light, which not only shapes form in his pictures but also symbolizes spiritual transformation, “spiritualizing" the figures of people which emerge from nothingness back into life, and to which the artist lends a thick materiality (“Sitting Figure with a Lantern"). In another series of images, eager to create “a purified image of enlightened flesh", he applied the subtlest shades of black, striving to achieve the stunning transparency and ephemeral quality of the figures whicih inhabited Fedorov's universe (“Composition with an Angel"). Fedorov believed that the human being, who previously only looked up at the sky, was bound sooner or later to become a “swimmer" across the universe. For the second half of the 19th century it was an absolutely utopian statement - but one which proved to be prophetic. Impressed by these ideas to populate other planets, Chekrygin produced his “Composition", an amazing image of Fedorov's future world, in which the newly reborn, immortal individual manages the “senseless" cosmic forces.

Chekrygin translated Fedorov's project of universal salvation into the compelling and persuasive idiom of visual art. Produced with soft-pressed charcoal and graphite, his pictures captivate the viewer with their perfection. Through his dynamic style, based on the beauty of flexible, smooth lines and deep glimmering chiaroscuro, he achieved a stunning picturesque quality in his imagery. Tellingly, Chekrygin regarded all that he created in the last two years of his life as fragments of a fresco - this reveals the passion that he had for monumental forms, which could reflect the entire harmony of the universe. Zhegin recalled: “The approach to space, composition, colour and texture itself - everything revealed in him the soul of a great fresco artist. He was even at that time talking about frescoes as his lifelong commitment, brushing aside all the trivia of everyday life that could get in the way of carrying out this ‘most important project'."[13] The series “Restoring the Dead to Life", in which every composition seems like a fragment of a grand mural, became Chekrygin's main creation. Bakushinsky characterized the artist's works on this theme as a “stirring artistic vision": they reflected “the great joy of anticipation of the new heaven and the new earth - the new human being in new, heretofore unseen social and cosmic relations".[14]

Multi-figure Composition. Five details. 1921

From the series “Restoring the Dead to Life” (1921-1922). Compressed charcoal on paper. 48.4 × 38.7; 48.5 × 38.3; 48.7 × 38.2; 48.5 × 38.3; 48.8 × 38.7 cm

Working on “Restoring the Dead to Life", Chekrygin became close to the group of artists and writers who created, in the spring of 1921, the “Art and Life" alliance of artists and poets (known from 1924 as “Makovets"). His associates from among them saw in him a true innovator, a brilliant theoretician and philosopher, so it was only natural that he actively participated in the elaboration of the principal provisions of the alliance's manifesto and was the main exhibitor at its first show. Unlike the “leftwing" artists, the members of “Makovets" never rejected the achievements of realist art in the widest sense. The group's manifesto, titled “Our Prologue", clearly articulated Chekrygin's idea of reviving art while maintaining a “steady continuity from the great masters of the past and unconditionally reviving the organic and eternal foundation of art".[15] The “Makovets" artists were also attuned to the ideas of the transformative role and spiritual community (sobornost) of art championed by religious philosophers such as Berdyaev, Ivanov, Solovyov, Fedorov and Pavel Florensky.

Chekrygin set out these ideas in an article published in the “Makovets" magazine after his death. According to the artist, modern art provides only a glimpse of the forthcoming renovation of the universe - making “the soil ready for a synthesis of live arts... only then will art lay bare its hidden powers and become a triumph of the creative endeavour of heavenly architects building heaven."[16] Fedorov's idea about the rise of a new productive art to shape the universe of the future was of paramount importance to Chekrygin. In his treatise “On the Cathedral of the Reviving Museum" (1921), dedicated to the philosopher's memory, Chekrygin created an august image of his cosmic church-cum-museum, in which learning and art were to come together within the fold of a living religion that united knowledge and faith. As he wrote: “The Son of man knows that he is not called to destroy the rise of the world but to complete its ascent in a purity undreamed-of, to open up the beauty of the blossom of the earth and the universe in a new and perfect freedom and incorruptible light."[17]

Chekrygin's art is as original as his personality. He not only possessed singular creative talents but also had a propensity to think philosophically and at length about life and art. Zhegin remembered: “His life was remarkable for its inner intensity and integrity... He certainly couldn't be unaware of his singularity. ‘I'm not a genius, but I'm touched by genius,' he told me once."[18] Nor could the artist's friends fail to notice his prophetic ability. Chekrygin, it seems, had a rare aptitude indeed for seeing the future. Thus, long before his tragic death, he wrote in one of his letters: “I don't know what my life's journey will be, but I have a premonition of it, and like a road at night, here it is, before my very eyes - and of my end: a violent death."[19] Unfortunately, this terrible prophecy was fulfilled when the artist had only just turned 25. Although his life proved very short, Vasily Chekrygin succeeded in finding his unique path in art, leaving to posterity a vast artistic legacy, a large part of which consists of graphic pieces, whose compelling, impressive imagery reflects both the spirit of the revolutionary age and of Russian religious thought.

- Quoted from: Murina, E.; Rakitin, V. “Vasily Nikolayevich Chekrygin”. Moscow: 2005. P. 21. Hereinafter - Murina, Rakitin.

- Bakushinsky, Anatoly. ‘V.N. Chekrygin’. In: “Russian Art”. Moscow: 1923. Nos. 2-3. P. 15.

- Vasily Chekrygin died on June 3 1922, after he was accidentally hit by a train between Pushkino and Mamontovka stations.

- Chekrygin’s innovative artwork was first exhibited in the winter of 1913-1914 at the 35th (Anniversary) exhibition of the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture; as punishment for his participation in the show, the Levitan stipend that he was receiving was suspended for one year; this, in turn, caused him, in February 1914, to leave the school where he had successfully studied for three years.

- “‘Makovets’ (1922-1926): A Collection of Materials on the History of the Group”. Moscow: 1994. P. 94.

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. “I! Illustrations by Vasily Chekrygin and L.Sh.”. Moscow, Kuzmin and Dolinsky Publishing House: 1913. L.Sh. - Lev Schechtel (Zhegin). A sketch of the cover of the book featuring four poems was designed by Vladimir Mayakovsky.

- Zhegin, Lev. “A Memoir of Vasily Chekry- gin”. Edited, with preface and annotations by Nikolai Khardzhiev. In: “Panorama of Arts”. Moscow: 1987. No. 10. P. 212. Hereinafter - Zhegin.

- Zhegin. P. 200.

- Nikolai Fedorov’s works were published in 1906-1913 as “The Philosophy of the Common Cause” by the philosopher’s friends and students, Vladimir Kozhevnikov and Nikolai Peterson.

- Fedorov, Nikolai. “Works”. Moscow: 1982. P. 633.

- Berdyaev, Nikolai. ‘The Religion of Resusc- itative Resurrection (Nikolai Fedorov’s ‘The Philosophy of the Common Cause').' In: “Fantasizing About Earth and Heaven”. St. Petersburg: 1995. P. 190.

- Murina, Rakitin. P. 218.

- Zhegin. P. 215.

- Bakushinsky, Anatoly. Studies and Articles. Moscow: 1981. P. 172.

- ‘Our Prologue’. In: “Makovets: A Magazine of Arts”. Moscow: 1922. No. 1.

- Chekrygin, Vasily. ‘On the New Emerging Stage of Pan-European Art in the Making’. In: “Makovets: A Magazine of Arts”. Moscow: 1922. No. 2. P. 14.

- Murina, Rakitin. P. 250.

- Zhegin. P. 210.

- Murina, Rakitin. P. 217.

Compressed charcoal on paper. 34.4 × 27 cm

Sketch for the composition "Uprising". Compressed charcoal on paper. 42.8 × 38 cm

Charcoal, lead pencil on paper. 15.6 × 12 cm

Compressed charcoal, lead pencil on paper. 19 × 17.1 cm

Sketch. Compressed charcoal on paper. 43.4 × 27.8 cm

Charcoal on paper. 48.5 х 41.6 cm. Gift of George Costakis, 1977

Compressed charcoal on paper. 22.7 × 20.5 cm

Charcoal pencil, fixer on paper. 21.6 × 23.3 cm. Gift of Alexei Sidorov, 1969

Sanguine on paper. 29.7 × 22.4 cm

From the "Crazy People" series. 1921-1922. Charcoal on paper. 26 × 25.6 cm

Compressed charcoal on paper. 22.7 × 27.8 cm

Compressed charcoal on paper. 31.6 × 30 cm

From the series “Restoring the Dead to Life” (1921-1922). Charcoal on paper. 30.8 × 23.8 cm

From the series “Restoring the Dead to Life” (1921-1922). Compressed charcoal on paper. 36.3 × 28.3 cm

From the series “Restoring the Dead to Life” (1921-1922). Charcoal on paper. 24.2 × 28.8 cm

From the series “Restoring the Dead to Life” (1921-1922). Lead pencil on paper. 25.5 × 37.8 cm

From the series “Restoring the Dead to Life” (1921-1922). Charcoal on paper. 37.8 × 44.1 cm