Restoration: the Discovery of a New Artwork by Yuri Pimenov

The paintings of old masters can sometimes harbour many secrets, which intrigue art fans and connoisseurs alike. A secret can be linked to a painting’s creation or its survival, but sometimes it hides within the painting itself, beneath layers of paint, waiting to be discovered by researchers and restorers.

There are many examples of paintings that are transformed once they undergo the painstaking work necessary to reveal hidden images and remove varnish darkened by age - Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch” is just one such example. The use of X-rays in analysis allows us to see aspects of the artist’s individual technique that are hidden from the naked eye - the steps in a painting’s creation - and sometimes reveals another painting beneath famous works, painted over by the artist. It was with the help of X-rays that the ‘lost’ painting by Isaak Brodsky “Alley in a Park in Rome” (1911) was rediscovered. It transpired that, in 1930, the artist had painted “Alley in a Park” over the original work, maintaining its composition but changing the clothes of the children and passers-by and adding trees. Ilya Repin often painted over his works: for example, the painting “Nun” is, in fact, a repainted portrait of Sofia Repina, nee Shevtsova.

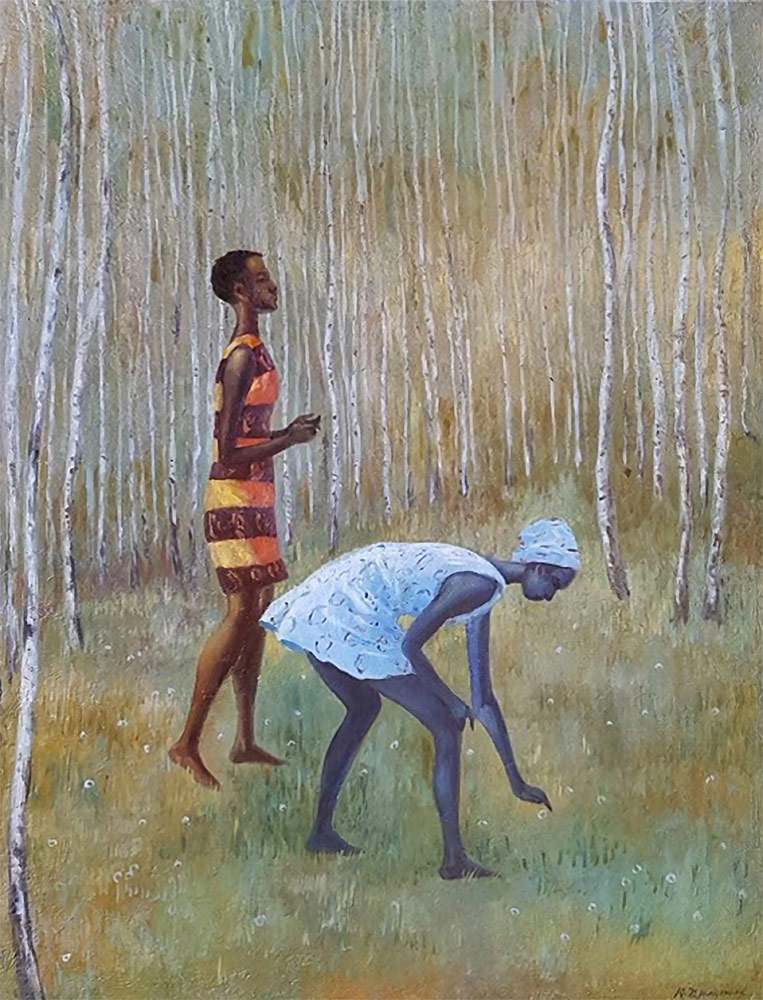

Yuri PIMENOV. Black Women in a Forest near Moscow. Late 1960s – early 1970s

Oil on canvas. 61.4 × 50.3 cm. Private collection, Moscow. The painting after restoration

When Pablo Picasso and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin didn’t have fresh canvases to hand, they often painted directly over previous works. Other artists, in contrast, applied a primer to the canvas before painting over their previous pieces, which makes it possible to peel back the layers and present a previously unknown new painting to the world. This was exactly the case with Yuri Pimenov’s work “Black Women in a Forest near Moscow” (late 1960s - early 1970s), beneath which was discovered the sketch “Venice. Bridge over a Canal” (1958).

Yuri PIMENOV. Venice. Bridge over a Canal. 1958

Oil on canvas. 61.4 × 50.3 cm. Private collection, Moscow

Detail of the painting after restoration

It was acquired in the USA by a collector from Moscow, who considered their purchase an extremely fortunate one, given that the works of Pimenov are largely located in museum collections and are infrequently available to buy. The painting “Black Women in a Birch Forest” was known only from the catalogue of an exhibition held in Tokyo’s Gekkoso gallery in 1975 and a description by the artist Igor Dolgopolov in the book “Yuri Pimenov” (2009). According to his account, all the paintings included in that exhibition were sold. The painting bought by the Moscow collector is a version of the famous one. When Russian experts examined it, they were struck by the thick, yellowed layer of varnish that covered the oil paint and which was not at all characteristic of the artist’s works. The varnish gave the work a monochrome appearance, and the owner - on expert advice - turned to the restorer Vasily Ruga to strengthen the pigment layer and remove the yellowed varnish. When Ruga analysed the painting, he noticed that the colour of the paint visible through the craquelure did not form part of the colouring of the piece, which allowed him to surmise the existence of another work hidden below the surface. With the help of X-rays, it was revealed that, beneath “Black Women in a Forest near Moscow,” there was indeed another painting, an upside-down urban landscape. Having done a number of tests, Ruga discovered that the artist had applied a layer of water-based primer over the earlier work before beginning the new painting. With time, this layer of primer became thinner and the bonding with the paint became weaker, leading a previous owner to cover it with a thick layer of varnish to strengthen the surface, a varnish that ultimately yellowed with time. This discovery led to the idea of peeling apart the various layers, given that the presence of the primer meant that the upper layer of paint was not in direct contact with the lower layer, which meant that there was a real chance of dividing the two compositions and transferring the upper painting to a new canvas.

The process of cleavage or separation between layers of paint is one of the most challenging tasks related to the restoration of paintings. Igor Grabar approached the problem as far back as the 1920s in the research and administrative centre he founded for the study and preservation of artistic treasures (now known as the Igor Grabar All-Russia Art Research and Restoration Centre) and, since then, the technique has continued to develop.

In the early days, the exfoliation of small fragments of later sections of paint was carried out with the aid of acetic acid. In the 1940s, well-known restorers, such as Vasily Kirikov, Viktor Filatov and Viktor Bryagin, carried out research into the process, on which basis later experts concluded that its success is often largely dependent on the talent and knowledge of the restorer themselves.

In the 1950s, restorers abandoned the use of acidic and alkaline solvents due to the effect their fumes had on pigments and paint layers. Restorers decided to adopt “volatile” solvents that posed no danger of penetrating deep into the layers of the actual painting. In the 1970s, researchers at the All-Russian Central Scientific-Research Laboratory for the Conservation and Restoration of Artistic Treasures in Museum Collections concluded that it is best to strip layers from small sections – around 10 x 10 cm - of a painting at a time before joining them carefully together Research into the cleavage was also undertaken abroad. Of one example, described in a paper on restoration, it was written: “a metal chest was prepared with a piece of fleecy fabric soaked in a solvent laid at the bottom and a metal grille placed on top to hold the artwork.”[1] The use of such a system means that the upper layers of the painting are acted upon by the vapours of the solvent being used.

To this day, no universal method of separating between layers of paint has been invented. Everything depends on the painting or icon in question and an individual strategy is adopted in each instance.

The preparations for the cleavage of this painting began with the creation of an appropriate base onto which the upper layer of oil paint could be transferred. A classic doubling canvas was prepared on a sub-frame, then covered by a series of layers - the first made up of starch, the second of 5% sturgeon glue, the third of 7% sturgeon glue without honey and the fourth of sturgeon glue with honey.

In order to protect the upper layer of paint from damage during the transfer, a protective paste was applied to its surface. This was done using cold 5% sturgeon glue to avoid it penetrating to the layer of water-based primer beneath. At the same time, it was necessary to prepare a film that would preserve the layer of paint applied by the artist. The restorers put together a box the same size as the painting’s canvas, the bottom and sides of which they covered in polyethylene plastic. They then poured a pool of PVB 10% solution diluted with ethanol into the bottom of the box in order to form the actual film. Even when completely dry, this film came away from the polyethylene plastic and, most importantly, maintained its elasticity. They placed the film atop the protective paste now covering the upper layer of the painting, having first wiped the paint with alcohol to give it a temporary stickiness lasting just a few seconds (until the alcohol evaporated). They then smoothed the film with a fluoropolymer spatula to make sure that it was lying smoothly across the entire surface and that no air bubbles were trapped between the layers.

The next step was to select the type of solvent that would be used to separate the layers. Tests were carried out to this end on a small section of no more than 1 x 1 cm. The task was a complex one, insofar as the solvent had to have very specific properties - it had to be capable of penetrating the upper layer of paint and the primer without affecting the painting lying beneath. After a thorough series of experiments, a suitable solvent was identified, consisting of one part white spirit, one part water and one part alcohol. The upper layer was softened by the alcohol fumes - but held together thanks to the protective paste and PVB film - while the water-based primer between the paintings became more elastic. However, as the alcohol quickly evaporated, its effect was maintained by the more stable white spirit (which doesn’t dissolve oil paint) and water, which prevented the fumes from penetrating any further into the layers of paint. In this way, the mix of solvents acted only upon the upper layer of paint and the water-based primer, leaving the lower layer of paint untouched. All that was left was to decide upon the length of time the painting was to be exposed to the solvent mixture - anywhere from 30 minutes to three hours was possible.

In the end, the following process was developed: the painting was generously coated in the solution (one part white spirit, one part alcohol, one part water) for a moderate exposure time of two hours, before an incision was made using an ophthalmic scalpel along the upper edge, beginning from the corner. Then, the restorers began to remove the upper layer of paint, supporting the pigment with a pair of tweezers and working gently to prevent the layer from tearing. It was necessary to slice the primer roughly in half, so that a portion of it was left on both the upper and lower layers of paint, protecting them from harm. When a significant portion of the painting was revealed, the paint layer began to dry out. In order to prevent this, it was essential to dampen it from both the inner and outer sides (in those parts that had already been separated) using a vaporiser filled with a carefully selected solvent. Once approximately 20% of the painting had been separated in this manner, the upper layer was gradually rolled onto a drum to prevent any fractures. The principle of rolling paintings in the process of cleavage mirrors that of rolling oil paintings for transportation.

The work demanded speed and intricate precision. It was made more complex by the highly textured nature of the painting hidden beneath, which meant that the slightest slip could have caused the loss of a thickly applied brush stroke. It was also clear that the process could not be paused even for a moment - from start to finish, it lasted close to eight hours.

Immediately after the process of cleavage had been completed, and while the painting wrapped around the drum still retained its elasticity, it was transferred onto the doubling canvas. The work was copied from the roll onto the new base. The restorers then smoothed the work through a fluoropolymer film and wrapped it in a large quantity of paper before placing it under a marble press for stabilisation. A day later, seeing that the excess moisture and solvent had not been fully absorbed, they replaced the paper in order to complete the process. They replaced the paper repeatedly over the course of three days, and then kept it under the marble press for another two weeks to ensure that the transferred layer was entirely stabilised on its new base. The second, underlying layer was also strengthened, using 5% sturgeon glue as rapidly as possible, and pressed under a weight for 24 hours.

Two weeks later, after the painting was completely dry, the cigarette paper was removed with the help of a cotton wad moistened in warm water in just the same way as protective seals are usually removed.

The cleavage was carried out successfully, but several months’ worth of restoration work was still required before the artist’s paintings could be presented to the general public. Yuri Pimenov’s finely executed “Black Women in a Forest near Moscow”, with its complex colouring, was revealed fully after the removal of the thick layer of yellowed varnish. The painting that had been hidden underneath was revealed to be, as had been anticipated, the exquisite Italian sketch “Venice. Bridge over a Canal” (1958). We can only speculate as to the reasons why, 10 years after its creation, the artist decided to paint over it.

The professional knowledge, intuition, inner certainty and craft demonstrated by the restorer Vasily Ruga have enabled us to enrich the historiography of Pimenov’s cultural legacy and add to the public’s understanding of the exhibition of one of the classics of Soviet art, which was presented in a major exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery in 2021.

The experts listed below rated the restoration work highly:

Aleksei Rudyagin, artist and first-category restorer;

Vladimir Markovin, artist and higher-category restorer;

Leonida Trubnikova, higher-category restorer;

Larisa Yasnova-Golitsyna, artist and second-category restorer;

Igor Vinogradov, first-category restorer;

Eugenia Alyokhina, art historian;

Lyubov Lapteva, art historian and expert on the art of Yuri Pimenov;

Aleksei Berezin, restorer, expert-technician.

- Viktor Filatov, Restoration of Russian Icons. Moscow, 2007

Details of the painting before the restoration

Details of the lower middle part of the painting before the restoration, with a pigment loss, where one can see the underlying paint layer of a different painting

After the transfer of the upper paint layer onto a new base

Test section of layer separation

The painting after the layer separation

The painting after reinforcement of the artist’s paint layer covered with a protective paste, upon thorough removal of surface contamination

The painting after restoration

The painting after restoration