WINDOW TO THE WEST

* Natalia Avtonomova, art critic, curator, specialist in Russian art of the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Head of the Department of Personal Collections of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. Honoured Arts Worker of the Russian Federation.

October 2022 marks 100 years since the opening of the legendary First Russian Art Exhibition, which took place at the Van Diemen Gallery in Berlin. It is difficult now to appreciate the significance of this far-reaching exhibition for Russia and for Western Europe—it undoubtedly played a key role in the development of experimental European art on through the 1920s and 1930s. The isolation caused by the World War II and various revolutions having subsided, in Europe new friendships and cultural exchanges arose between artists across the continent, as well as a wave of avant-garde exhibitions. Russian non-figurative art—“Malevich’s suprematism” and “Tatlin’s pro-constructivism” — began to gain popularity and spread quickly across art’s world stage. The constant flow of emigration from Russia undeniably facilitated this process.

ALEXANDER DREVIN. Non-Objective Painting (Artistic Composition). 1921

Oil on canvas. 124 × 95.5 cm. © Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The first half of 1922 saw a dialogue established within European cultural life between the numerous avant-garde groupings such as the Dadaists and Constructivists and the process of exchanging ideas in the cause of creating a single aesthetic platform also intensified. Meetings between artists also took place in Europe that year: in Paris, preparations were made for the international congress; the Founding Congress of the Union of Progressive Artists was held in Dusseldorf in May; and in September, Weimar hosted the Constructivist International Congress, with guests such as El Lissitzky, Hans Richter, Theo van Doesburg, Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, Tristan Tzara and Jean Arp. This “cultural kaleidoscope of a year” saw the appearance of new periodicals, international in spirit and in aspiration, in several European cities—in Berlin, the legendary journal “Veshch-Objet-Gegenstand”; in Brussels, the magazine on new plastic culture and authority on Neoplasticism “Style” (De Stijl); and in Vienna, the left-wing avant-garde “Ma”, published by Hungarian Lajos Kassak.

The concurrency in aspiration among many of the artists who overcame previous divisions expressed itself in a departure from the confined spaces of the studio and integration of their work into the community as much as possible, be it through architecture, interior design, stage design, political propaganda or advertising. “Not arranged space, but shaped reality” was the order of the day[1].

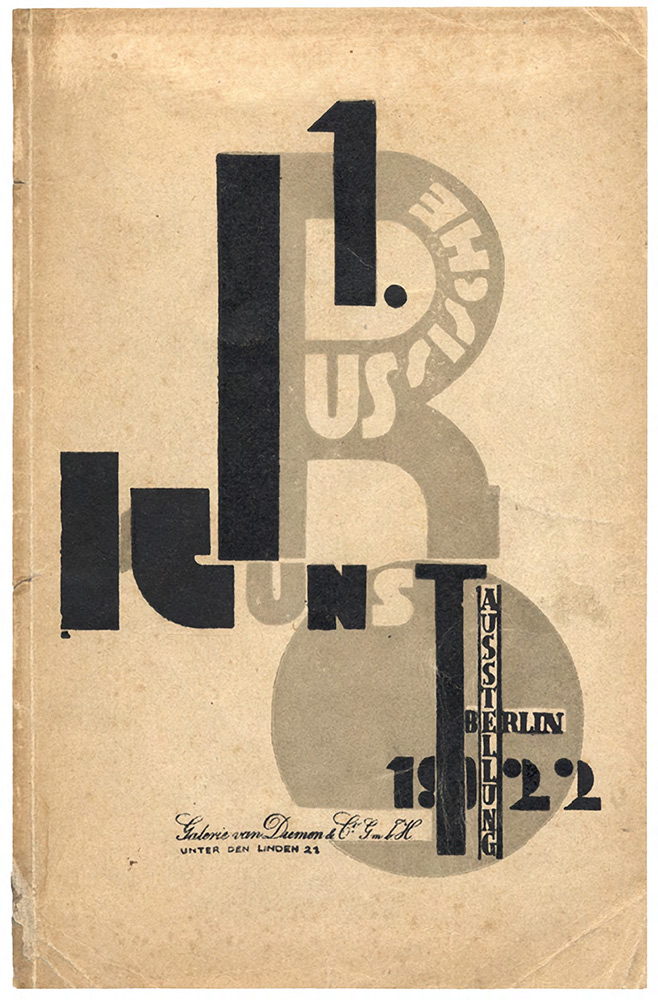

The catalogue of the First Russian Art Exhibition in Germany. Berlin, 1922.

Cover by El Lissitzky and introduction by David Shterenberg

Berlin was Europe's largest cultural centre in the 1920s, the “capital of the United States of Europe”, as Herbert Walden[2] called the city. In Ilya Ehrenburg's words, “the whole world was watching Berlin” and Russian art played a notable role there[3]. Russian emigration to the German capital rose steadily during this period: some 250,000 people of diverse backgrounds made up the diaspora. “Russian Berlin” was a meeting place and transit point, although it existed in an entirely self-contained state and was even distinguished by a certain insularity. “The city was the ideal training ground for those who wanted something new—for experimentalists, lone enthusiasts, reformers, revolutionaries[4]. Famous artists' cafes on Nol- lendorfplatz, such as Leon, Romanische and the famous “House of Arts”, were literature centres visited variously by Marina Tsvetaeva, Sergei Yesenin, Boris Pasternak and Vladimir Nabokov. The “publishing boom”, or in other words, the abundance of newspapers and journals being published in Russian, sparked an interest in Russian culture. Bubbling Berlin also became an attractive place for avant-garde artists visiting the capital, such as Alexander Arkhipenko, Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, Ivan Puni and Ksenia Boguslavskaya, Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, Serge Charchoune, El Lissitzky, Naum Gabo, Antoine Pevsner, Nathan Altman and others. Puni and Boguslavskaya's workshop, not far from Nollendorfplatz, became the meeting spot for Russian, Hungarian, Lithuanian and German artists. Both of the workshop's owners frequented the Board of the House of Arts, lead by Nikolai Minsky, Andrei Bely and Aleksei Remizov. The emigre cabaret “Blue Bird”, with a halo of exoticism and a line-up fit for the kitsch Russian soul, attracted an audience and lovers of all things Russian, including the head of Berlin's famous Der Sturm Gallery, Herwarth Walden.

In autumn 1921, the artist El Lissitzky was posted to Berlin from Russia, in order to establish contact with the artists and culture professionals of Western Europe. In March 1922, together with the writer Ilya Ehrenburg, who was living abroad as a correspondent, the two began to publish the international journal “Veshch” (“Object”), about contemporary art. With versions in Russian and German, the journal promoted the creative principles of constructivism[5]. The first issue began with a flagship article titled “Blockade of Russia Comes to an End”. The appearance of Veshch was considered by the article's author to be a sign of a new exchange of experiences and accomplishments between young artists from Russia and the West. “Finally, we realised the idea that we had come up with long ago in Russia-publishing an international journal of contemporary art. Everyone creating new values or helping in the creation of them has united around it,” wrote Lissitzky[6].

At this time, articles by Konstantin Umansky were appearing in the Munich journal “Ararat” (one of which was about the works of Vladimir Tatlin); his hugely informative book “New Art in Russia 1914-1919” had just been published. In Germany, Tatlin's artistic concept was adopted as a theory which blurred the lines between art and machine technology, and his design of the “Monument to the Third International” inspired Berlin Dadaists to create the series “Tatlinist Mechanical Constructions”. “Art is dead. Long live the new mechanical art of TATLIN!” — read the famous poster by German Dadaists George Grosz and John Heartfield[7]. It was initially proposed to name the Dadaist journal “Die Pleite” (“Collapse”) after Tatlin instead. Many German artists had created their own masterpieces based on the theories of the “great modernist” and “artist-engineer”, and leader of the German Dadaists Raul Hausman created the collage “Tatlin at Home” (1922) in honour of the Russian constructivist.

At the end of 1921, Wassily Kandinsky was sent to Berlin for the establishment of an international branch of the RAKhN — the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences — as well as to teach at the new educational centre Bauhaus, founded in Weimar in 1919 by the famous German architect Walter Gropius, who had invited Kandinsky. A unique situation came together at Bauhaus: Gropius put together an international avant-garde-oriented group of teachers and students, which included the leading artists and architects of the time: Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, Hannes Meyer, Mies van der Rohe. The school was conceived as a major pan-European artistic experiment and Kandinsky found himself amongst like-minded peers.

Kandinky's personal standing and the significance of his art in prewar Germany, as well as the friendly ties he had maintained with many German artists from the Munich period of his life, meant that he was well placed to establish contact between Russians and Germans.

The year 1922 marked drastic changes in relations between Russia and Germany. Perceptions of Soviet Russian art shifted substantially following the “First Russian Art Exhibition”, which had presented a comprehensive view of artistic developments in Russia as well as achievements in the area of arts education. The exhibition fuelled the West's acknowledgement of the authority of Russian innovators and familiarised them with the state and level of vocational training in Soviet Russia. Abram Efros aptly summarised the situation: “the Window to the West is beginning to open, slowly, with great effort, inch by inch — but it's opening, undoubtedly.”[8]

In March 1922, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee in Moscow created the Organising Committee for Soviet Art Exhibitions Abroad under the direction of Anatoly Lunacharsky. The avant-garde artists Tatlin, Shter- enberg and Malevich, as well as the art historian Punin, were all active members of the International Branch of the Fine Arts Division. Earlier, in 1921, David Shterenberg had been instructed to design “a plan to organise artistic and industrial exhibitions abroad, in cooperation with the People's Commissariat of Foreign Affairs.”[9] In February 1922, Shterenberg began organising exhibitions of Russian art in Berlin, in the Van Diemen Gallery, which provided exhibition space on favourable terms. The majority of the artists involved doubted the success of the planned show among international viewers because, they thought, the ratio of “left-wing” to “right-wing” artists did not favour the latter. “The ‘Non-Objectivists' and ‘Suprematists' are represented with a vast number of circles, squares, triangles and parallelograms — in colour and in monochrome (there is even a ‘white on white')” declared the magazine “Firebird”[10]. Yakov Tugendhold, writing after the exhibition's end, noted, “delivered by Shterenberg, practically for a pittance and relying on pure luck, and taking nearly a month on the way, this exhibition went from a trial run to a real, official event, a foreign debut for the People's Commissariat, for the benefit of the Committee for Famine Relief.”[11]

The organisers of the First Russian Art Exhibition in Germany. Berlin, October 1922.

From left to right: David Shterenberg, Head of the Department of Fine Arts, Narkompros (Peoples Commissariat of Education); D. Marianov, Representative of the Russian Security Services; the artist Nathan Altman; the sculptor Naum Gabo; and Friedrich Lutz, director of the van Diemen & Co Gallery. Photograph

The “First Russian Art Exhibition” opened in Berlin on October 15, 1922, and proved a success. There were 15,000 visitors recorded in Berlin alone and, afterwards, the exhibition was moved to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where it ran from April 28 to May 28, 1923.

According to the memoirs of Nikolai Denisovsky, the exhibition's secretary, posters were printed and a catalogue published right there in Berlin to designs by Lissitzky. Within the catalogue, the cover of which featured the same design as the poster, a list of the works on display was printed on cheap paper, alongside an illustrated section on coated paper. Here were presented in black-and-white reproductions the works of 50 artists of the most disparate creative inclinations, from Arkhipov to Malevich. The catalogue's foreword was written by the exhibition's chief organiser, or commissar, David Shterenberg: “During the Blockade, Russian artists tried more than once to unite with their Western comrades, writing appeals, manifestos and more, and only now with the present exhibition can we talk of any sort of real step toward rapprochement. At this exhibition, we want to display the creative achievements of Russian art during the War and the Revolution. Russian art is very young still.”[12] Shterenberg pointed out the selection principles the Committee had followed when choosing works to show at the exhibition: “Only works from varying artistic movements can show how energetically Russia has been developing in recent times. The works of leftist groups show that kind of laboratory work that propels the construction of new art forms... We want this first attempt at demonstrating the artistic strength of our country not to be the last, and we hope that our Western comrades, whom we would love to see in Moscow and Petrograd, won't be left waiting for long. Together with the art flourishing and developing in older, more traditional forms, there is a new kind of art emerging, one which will try to meet the challenges of the present age and which tries to use the forces unleashed by the Revolution for the benefit of art.”[13]

The catalogue also included articles by German experts such as the National Art Commissioner Edwin Redslob and the writer Arthur Holitscher, which paid special attention to the unusual conditions of the war and the blockade under which the works on display were created.

The exhibition comprised more than 1,000 works of art, created mostly in the preceding five years from 1917 to 1922 — more than 200 paintings, 500 drawings (sketches, watercolours and engravings), a small number of sculptures, designs of theatre sets, costumes, architectural projects, and posters, and more than 200 decorative pieces: ceramics, stone works, embroidery, figurines, toys and clothing designed by Nadezhda Lamanova. Also shown were works by artists from different unions — the Union of Russian Artists, the “World of Art”, the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions, the Moscow Society of Artists, Jack of Diamonds, the Society of Young Artists, the Makovets, the Union of New Movements in Art, UNOVIS (Champions of the New Art), Zhivskulptarkh (Committee for the Synthesis of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture) — as well as works by artists living abroad — Alexander Arnsh- tam, Ksenia Boguslavskaya, Wassily Kandinsky, Nicholas Millioti, Ivan Puni, Marc Chagall, David Burliuk, Varvara Bubnova and Serge Charchoune among them.

Most artists of the older generation were well known by German art lovers from the prewar exhibitions of the Munich and Berlin Secessions. On display were Realist works such as Abram Arkhipov's “Reading the Papers” and “Decembrists in Chita” by Alexander Moravov, identified by Lissitzky as pieces “concordant with the revolutionary age”, as well as nostalgic, retrospective pieces by the artists of the “World of Art”, and Cezannist works by the Jack of Diamonds group. The press also noted pieces by Konstantin Korovin, Leonard Turzhansky, and Alexander Hausch, and critics admired Igor Grabar's “beautiful emerald Russian landscapes”, Stanislav Zhukovsky's delightful “images of winter” with their violet shading, and the “rich” subject matter of Boris Kustodiev's works. He was named the “Russian Titian” for his painting “Merchant's Wife Taking Tea by the Samovar”.[14]

In the central rooms of the gallery's upper floor, “leftist” artists, including Alexander Drevin, El Lissitzky, Kazimir Malevich, Olga Rozanova, Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Stenberg, Georgy Stenberg and Vladimir Tatlin among many others had their works displayed. Works by Robert Falk and Vasily Rozhdestvensky, as well as samples of “industrial art”, were shown in separate rooms.

Among these artists, the works of Nathan Altman, one of the organisers of the Berlin exhibition, were particularly highly praised. His drawings of Vladimir Lenin (1920) and paintings such as “Russia. Labour” (1921) and “Petro- Commune” (1919-1921) had great social resonance. They were written about as works with Socialist content: “On a red square, with the colour of dazzling sunny joy and the radiance of happy will, stand the strong, firm, resilient letters RSFSR. One feels that there is no force that could dislodge or destabilise them... Nathan Altman is a master whose art may be called revolutionary.”[15] Altman's work “Russia. Labour” was chosen by the Halle Artists Group as the cover for their weekly publication “Das Wort” in February 1923 and the head of the group Karl Volker associated his work “Greetings to Soviet Russia from a German Artist” with Altman's painting.

The theme of revolution continued unbroken and dominated the mass-propaganda section, which, according to Lunacharsky, gave German viewers a “taste of Soviet Russia”. “Art has gone out into the streets; it lives in the streets and with the streets.”16 The exhibition displayed 20 posters from the period of the Revolution and the Civil War, as well as 10 ROSTA (Russian Telegraph Agency) posters by Vladimir Mayakovsky, a series of linocuts by Vladimir Kozlinsky (“Petersburg During the Revolution”, 1919) and eight woodcuts by Nikolai Kupreyanov (“Armored Trucks”, 1918; “Kremlin”, 1921; the album “Civilian Life During the Revolution”). One visitor to the exhibition noted that “the pictures capture you, whisk you away in a hurricane to Russia, towards the fiery-red letters “RSFSR” splattered all over the canvas, transfixing you.”[17]

Also marked as new experimental developments, the architectural projects displayed at the show were full of ideas for new buildings and images of cities of the future. Anton Lavinsky displayed his project “City on Springs”, El Lissitzky his proun “City” [proun was the name that Lissitzky gave to the abstract, geometric works that he produced in the early 1920s], and Naum Gabo the electrical power station design “Regarding (the Plan for) the Electrification of Russia”. Artists from the “Zhivskulptarkh” collective exhibited their projects for “socially new buildings like the House-Commune. and the House of Soviets.” Experimental “spatial constructions” were made using various materials and also presented in the sculpture section.

Adolf Behne, one of the closest associates of the architects Bruno Taut and Walter Gropius, wrote of the exhibition's content: “Kandinsky is not the dominant force here, and neither, of course, is Chagall. it is the Constructivists, the excellently showcased Malevich, Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Tatlin, Altman, and Gabo. What leading artists in every country want it is to directly shape life itself (Russians call it Productivist art). And Soviet Russia, from the very start, gave this great new objective every opportunity and an easy path.”[18]

It is interesting to note that, according to the German press, the Berlin show was significantly better than the seminal pre-war exhibitions of Russian avant-garde artists in the renowned Der Sturm gallery thanks to the comprehensiveness and diversity of its content. The role of discovering and popularising then little-known Russian masters such as Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall and Alexander Arkhipenko had fallen to its leader, Herwarth Walden. The renowned retrospectives of works by Russian avant-garde artists in Walden's Berlin gallery, as well as the publishing of their newest theories and reviews of their creations in his “Sturm” magazine, were defining moments in the pre-war “heroic” era of the European contemporary art scene. In 1921 and 1922, Walden organised exhibitions of the works of Ivan Puni, Serge Charchoune, and Lyubov Kozintseva-Ehrenburg and, in 1923, he was behind an exhibition at the Neue Kunsthandlung of models and sketches by Alexandra Ekster for Alexander Tairov's Kamerny Theatre, which was on tour at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin.

In the theatre section of the Berlin show, the German public were introduced to new Russian stage designs with experimental formal solutions and changes in the very language of scenography. Centre stage were 18 of Ekster's set and costume sketches for productions at Moscow's Kamerny Theatre and Jewish Theatre, including “Famira Kifared” (1916), “Salome” (1917) and “Romeo and Juliet” (1921). El Lissitzky also displayed his “theatre drawings” — sketches of figurines for an electro-mechanical staging of Aleksei Kruchyonykh and Mikhail Matyushin's opera “Victory Over the Sun”. Designs of innovative solutions for “sensational” theatre productions, including those of Georgy Yakulov for “Princess Brambilla” (1920), of Nathan Altman for “Uriel Acosta” (1921) and of Alexander Vesnin for “The Annunciation” (1920), were also on display.

“Propaganda ceramics” by artists from the State Porcelain Factory in Petrograd were well represented. Plates were decorated with portraits of Lenin and Karl Liebknecht, inscribed with revolutionary slogans such as “Workers of the World, Unite”, “Land for Workers” and “Long Live the Third International”, adorned with Soviet emblems, or a combination of all three. Small porcelain figures, such as Natalya Danko's “Policewoman”, enjoyed great popularity with the German public. Between 1921 and 1922, artists from the factory prepared a series of decorative works with inscriptions in German: Alexandra Shchekatikhina-Pototskaya's “Kampf gebiert Helden” (“Struggle Breeds Heroes”), 1921; “Russkiy i nemets. Proletarier aller Lander, vereinigt euch!” (“Russian and German [in Russian]. Workers of the World, Unite!”), 1921; and Alisa Golenkina's “Wir entflammen die ganze Welt mit dem Feuer der III Internationale” (“We Light up the Whole World with the Fire of the Third International”), 1922.

The exhibition also displayed works by students at the Moscow Higher Art & Technical Studios (Printing and Ceramics Departments), the Study and Work Studios for Decorative Arts, based on the former Central School of Technical Drawing of Baron Alexander von Stieglitz in Petrograd, and the Vitebsk Art Workshops, as well as the work of school pupils and younger children. It was the Berlin exhibition in particular, along with the active support of UNOVIS (Champions of the New Art) from Lissitzky, who was already working in Germany by the time the show opened, that helped to strengthen Malevich's standing and reputation as the leader of a new kind of art in the German world. The exhibition introduced German viewers to the creative works of students and followers of Malevich, united under the name UNOVIS. Coursework (24 compositions and 11 Cubist drawings) by students of the Vitebsk People's Art School (Lev Yudin, Anna Kagan, and Yefim Royak among them) showed the potential of this creative method and Malevich's pedagogical systems. Pieces by students at the Higher Art & Technical Studios (VKHUTEMAS), who, for the most part, would become organisers of the Society of Easel Painters a few years later, were also presented in Berlin and welcomed by the press.

However, the critics noted that there were gaps in the exhibition, which could be explained by the fact that “the artists themselves, especially the ‘academic' ones, not believing in the serious possibility of a foreign show, gave far from their best work”. “The Germans did not get quite the right impression of Russian art. It seems to them that the ‘leftist' movement is pushing through in Russia and that the realistic forms of art are simply living out their boring days. Furthermore, at our exhibition the Germans did not see any truly major works, with very few exceptions,” Lunacharsky noted, pointing out that the exhibition could fully reflect “neither today's, nor particularly tomorrow's art. It reflected only those specific conditions in which we lived during those years—namely, a burst of energy from the left flanks of pre-revolutionary art.”[19]

The issue of the exhibition's content was further muddied by the fact that, in December 1922 (the Berlin exhibition opened on October 15) more paintings and graphic works by many more contemporary artists were added, as well as sculptures, stage designs, porcelain and glass- work. The additions, all by young Russian artists, were to come from an exhibition at the Moscow-based Museum of Artistic Culture, which ran from December 25 to 27, 1922. “Izvestia” newspaper stated specifically that the works were destined for Berlin, to be included in the ongoing exhibition, and then on to Paris, where the Russian art show was expected to be deployed next. In Moscow, works by Projectionist artists (Pyotr Williams, Zenon Kommissarenko, Alexander Labas, Sergei Luchishkin, Salomon Nikritin, Kliment Redko, Nikolai Tryaskin, and Alexander Tyshler) were shown. Shterenberg, having returned to Moscow to collect the additional art for the Berlin exhibition, took pieces by the aforementioned artists, as well as works from Alexander Vesnin, Ivan Kudryashov, Yuri Pimenov, Liubov Popova, Nadezhda Udaltsova and several other artists (paintings, illustrations, constructions, theatre set designs). He also took 40 sculptures by Sergei Konyonkov, as well as pieces of porcelain and glassware — in total, 193 works from 19 artists. It is known that the Berlin show paid for itself and any net gains from the exhibition and the catalogue, published in German with help from the “Workers International Relief” publishing house, were earmarked for hunger relief in Russia.

The exhibition also had financial benefits for Russian artists. During its run, about 50 paintings and a large number of decorative objects were sold. The famous American contemporary art collector Katherine Dreier acquired pieces by Malevich, Udaltsova and Alexander Drevin, as well as El Lissitzky's Prouns, dimensional compositions by Kazimir Medunetzky, designs by Rodchenko and the Stenberg brothers and sculptures by Gabo, all for the “Societe Anonyme”. Mayakovsky wrote: “The Americans are buying up constructions, paintings, manufactured pieces ... the German papers generally state that it is thanks to these artists in particular that Russia's visual arts will grow.”[20]

“The Russians, more so than in Germany or France, have embraced a stronger movement, a more plastic and dimensional force” (Paul Landau)”.[21] “Russians are more straightforward and certainly more energetic in their art than us Germans”. (W. Spael).[22] Reflecting on the First Berlin Exhibition's significant influence, Otto Nagel noted: “The New Russia has aroused the sympathy of the progressive German intelligentsia. We became acquainted with new Russian literature, we were enraptured by the first Soviet films that we saw in Germany. The first exhibition of Soviet art, which took place in Berlin, inspired lively interest. Friendly ties with the Soviet intelligentsia have been established.”[23]

The Berlin exhibition came to be “the first bridge, introduced in the postwar period, between the cultures of Soviet Russia and the West”. “The first breach in the spiritual blockade with which the West has surrounded Soviet Russia has been followed by a second. Russian art has served as a battering ram,” wrote Tugendhold.[24] He continued in the same key to say that holding exhibitions in other countries “is one of the biggest factors in the cultural export and spiritual propaganda of the RSFSR.” In the Berlin newspaper “Vossische Zeitung”, the famous art critic Max Osborn wrote with great admiration of the first show of Russian art abroad since the October Revolution: “This promising, carefully organised exhibition proves to us all that the Soviet authorities do not at all represent a naked experiment trampling on all that went before; on the contrary, under their rule, creativity and spiritual strength have only flourished.”[25] In the French newspaper “Air Nouvelle”, the art critic Waldemar-Georges dedicated four articles to the event: “It is the greatest pleasure that finally a fresh gust of wind has blown from Russia in art that reflects the life of a true mass artist.”[26] In the paper “Vorwarts”, John Shikovsky wrote that “the Russians have created an independent artistic culture”[27] and Fritz Stahl reported for the “Berliner Tageblatt” that “I doubt that any of the stable-currency states could pull this off now. There is no doubt that there is a unique harmony between the revolutionary art of these artists and the revolutionary nature of Soviet power itself.”[28]

It was suggested that art of “the left” was merely “the art of artistic problems”. According to Tugendhold, “the true centre of the exhibition's gravity, its highlight, has been seen by the European press in the works of the younger currents of the Jack of Diamonds' and newer groups.”[29]

Max Osborn wrote for “Vossische Zeitung” that “at the exhibition, you feel a passionate ... desire to express in new forms that constructive energy that turns the government and the world economy over.”[30]

The main result of the cultural ties thus established was the exhibition of German art in Moscow in 1924. The First General German Art Exhibition opened in Moscow in the halls of the Historical Museum on October 18, 1924, later moving to Saratov (December 1924-March 1925) and then Leningrad (May-July 1925). It was organised by the Russian branch of the Central Committee of International Workers Relief (Mezhrabpom) together with the Commission for Foreign Aid under VTsIK, and constituted the first showing of German revolutionary art. It was suggested that each of the German artists present their three best paintings or sculptures (graphic art and architectural models were accepted for the exhibition only upon special agreement).

Around 500 works from more than 130 artists and architects were displayed, all united by the spirit of innovation and the desire to create new art. The exhibition was “universal” and represented a varied spectrum of creative attitudes in the German art world of the 1920s, as well as a large number of artistic groups: from the Secessionists to the pro-Communist “Red Group” (George Grosz, Otto Dix, Erich Drechsler, Franz Seiwert, Rudolf Schlichter, and Otto Nagel among them), as well as the “November Group” (including Rudolf Belling, Walter Dexel, and others), the “Union of Berlin Artists” (Hans Baluschek), representatives of the “Academy”, Bauhaus, Sturm and many more. Alongside paintings and sculptures, the exhibition displayed architectural models of workers' settlements and factory buildings, posters and graphic design. Renowned German artists Otto Nagel and Eric Johansson accompanied the exhibition to Saratov and Leningrad and, as Nagel later recalled, it roused great interest, with visitors standing in long queues just to get into the halls of the Historical Museum. After the show's closing, some of the pieces were acquired by the museum branch of the People's Commissariat for Education (Narkompros): five paintings, 17 illustrations and one sculpture, which were later transferred to the Museum of Modern Western Art.

In a foreword to the exhibition catalogue, Richard Oehring wrote of two of its special features: the first, a showcase of the works of “a group of German artists who deny apolitical art and make it their aim to artistically represent social justice and give realistic and clear forms to the working masses”; the second, a demonstration of the achievements of German architects who, thanks to Germany's technological progress, “created new, deeply efficient forms and architectural methods”.[31] The catalogue's other author, the renowned architect Adolf Behne, noted in his article “Trends in Contemporary German Art” the one-sidedness of the exhibition and the “unfortunate white spots” that appeared as a result of the fact that, in contrast with the First Russian Art Exhibition, the German exhibition was put together exclusively from the collections of the artists themselves and had no support from the state. Johansson wrote explanatory notes for the catalogue and provided descriptions of the participants and artistic groups.

Unlike the art of France, German art was known for its predominantly graphical origins and for being ruled by intellect and reason. In numerous reviews of the Moscow exhibition, a distinct sense of tragedy, grotesqueness and heightened anxiety was noted, particularly in the works of Dix, Nagel, Johansson, FelixmQller and other members of the Red Group and November Group. According to Alexander Fyodorov-Davydov, Expressionist intensity, pictorial acuity and formal dynamism were all inherent to these artists and their works and the sense of “universal rejection” and despair was shocking. Most of the works had a volcanic, explosive emotional force. The artists increasingly withdrew from reality, protesting against it. Figures of workers in the art of Heinrich Hoerle, Hannah Hoch, Albert Birkle and Karl Volker were often interpreted as hideous and grotesque, as victims of an ever more technology- focused world. A special emphasis was placed on erotic themes: sexual motifs in the works of Dix, Griebel, Hoffman, Nagel and Schlichter were noted for the hypertrophied scale of their naturalism and their fixation on detail — in them, one could sense the cynicism and chaos of the postwar period. “The horrible war... and its tragic consequences, which filled art with the figures of homeless cripples, widows, orphans, diseased children.”[32]

The exhibition demonstrated the undeniable blossoming of the art of drawing in Germany. Illustrations by Kathe Kollwitz, Grosz, Dix and Schlichter were attributed to the development of a new order in German art. These artists, part of the “Red Group”, united under the banner of the anti-bourgeois revolution. Satirical drawings of the “Verists”, as they called themselves, were their main theme. These included disfigured characters, grimaces of horror, mockery, anxiety and tension, protest and battle against the bourgeois lifestyle and the middle classes.

In connection with the opening of the German exhibition, the Academy of Art Studies hosted several talks by cultural figures, experts, and artists. At the meeting on October 19, Professor Aleksei Sidorov presented the paper “The Significance of Modern German Art for Russian Artistic Culture” and the artist Otto Nagel gave a brief explanation of “Contemporary Trends in German Art”, followed by talks from Fyodorov-Davydov (“German Art for Us”) and Ilya Kornitsky (“Form and Content of Modern German Art Based on Exhibition Materials”) on October 23. Leading Russian art critic Yakov Tugendhold wrote an overview in which he noted the importance of the general atmosphere of German art that surrounded the Moscow exhibition, how it was “ecstatic, filled with a heightened passion and an intensely agonising sharpness, a shift toward life's truths.”[33] “Truth” came to be the Verists' motto, as they saw it as their task to identify class conflict in art and use it as a propaganda tool.

Tugendhold, along with Adolf Behne, pointed out that the exhibition “had several gaping holes” — there were no works in the catalogue by a number of famous artists, for example, the classics of Expressionism like Franz Marc; only a small number of pieces by masters such as Oskar Kokoschka, Paul Klee and Emil Nolde were shown and there were no sculptures by Ernst Barlach or Wilhelm Lehmbruck.

The fact that in June 1923 the “Society of Friends of the New Russia” was founded in Germany (members included the artists Kathe Kollwitz and Max Pechstein and the critics Max Osborn and Adolf Behne) bore witness to the mutual interest that Russian and German cultural figures had in each other. From May 1924, the Society began to publish the journal “New Russia”, with contributions from Nadezhda Krupskaya, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Nikolai Semashko and Georgy Chicherin.

Mayakovsky wrote: “Despite trying to distance itself from us politically, Europe does not have the strength to suppress its interest in Russia; it tries to give this interest an outlet by opening up the vents of art.”[34]

In conclusion, we would like to express our hope that the 2022 exhibition in Berlin will serve as a memorial and attest to a continued interest in Russian art.

This article was written with the help of materials from the following publications:

- Yavorskaya, Nina. “First General German Exhibition in the USSR. (1924)” // “Cultural Life in the USSR. 1917-1927”. Moscow, 1975. p. 353

- Ol'brikh, Kh. 1922 “The Soviet Exhibition in Germany. Background and Lessons.” // “Links Between Russian & Soviet Art and German Artistic Culture.” Moscow, 1980. pp. 162-175

- Zump, G. “Exhibitions of German Art in the Soviet Union in the Mid-20s and Their Evaluation by Soviet Critics” // “Links between Russian & Soviet Art and German Art Culture.” Moscow, 1980. pp. 183-192

- Lapshin, Vladimir “The First Exhibition of Russian Art. Berlin. 1922. Materials on the History of Soviet-German Artistic Links” // Soviet Art Studies '82. No. 1 (16) Moscow, 1983. pp. 328-362

- Finkeldei, Bernd. “Under the Sign of the Square. Constructivists in Berlin.” // Moscow-Berlin /Berlin-Moskou. 1900-1950. Moscow, Berlin, 1996. pp. 157-161

- “Herwarth Walden and the Legacy of German Expressionism.” Edited & compiled by V. Kolyazin. Moscow, 2014

- Adkins, Helen. “Erste Russische Kunstausstellung. Berlin 1922” // Station der Moderne. Berlinische Galerie. Berlin, 1988. pp. 184-215

- Richter, Horst. I. “Russische Kunstausstellung. Berlin 1922” // Erste Russische Kunstausstellung. Berlin 1922. (Reprinted Cologne, 1988)

- Schirren, Matthias. “Soul and Act. Avant-Garde Architecture and City-Building in 1920s Berlin” // Moscow-Berlin / Berlin-Moskou. 1900-1950. Moscow, Berlin, 1996. p. 214

- Dmitrieva M. E. “Russian Artists and 'Der Sturm'". // Herwarth Walden and the Legacy of German Expressionism. Edited & compiled by V. Kolyazin. Moscow, 2014. p. 319

- Ehrenburg Ilya. “People, Years, Life." Moscow, 1990. p. 388

- Alms Barbara. “Der Sturm" in the Second Decade of the 20th Century. Internationalisation of One Art Project. // Herwarth Walden and the Legacy of German Expressionism. Edited and compiled by V. Kolyazin. Moscow, 2014. p. 64

- The Blockade of Russia Ends... Veshch (Object). 1922. No. 1-2. March-April. p. 1

- Rodchenko A. M. Article. Memoirs. Autobiographical Notes. Letters. (Compiled by V. A. Rodchenko). Moscow. 1982. p. 115

- Izyumskaya M.A. German Dadaists and Russia. Paths of Collaboration // Russia-Germany. Cultural Links, Art, and Literature in the First Half of the 20th Century. Materials from the academic conference “Vippers' Readings-1996”. 19th edition. Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. Moscow, 2000. p. 56

- Efros A. Us and the West. Artistic Life: Bulletin. 1920. No. 2 January- February. p.1

- Archives of D. P. Shterenberg. // cited in: Lapshin V. P. First Exhibition of Russian Art. Berlin. 1922. Materials for the History of Soviet-German Art Relations. Soviet Art Studies. 82. No. 1 (16). Moscow, 1983. p. 328

- Russian Art Exhibition in Berlin. Zhar-Ptitsa. 1922. No. 8. pp. 23-24

- Tugendhold Ya. A. Art Exhibition in Berlin. “Russian Art”. 1923. No. 1. p. 100

- Shterenberg D. P. Article for the Programme Leaflet for the Russian Art Exhibition in Berlin. Private archive. // cited in: Lapshin V. P. First Exhibition of Russian Art. Berlin. 1922. Materials for the History of Soviet-German Art Relations. Soviet Art Studies. 82. No. 1 (16). Moscow, 1983. p. 336

- ibid.

- Lukomsky G. Y. Kustodiev and Grabar. (Exhibition on Unter den Linden). On the evening of November 3, 1922. No. 176. // cited in: Lapshin V. P. First Exhibition of Russian Art. Berlin. 1922. Mate-rials for the History of Soviet-German Art Relations. Soviet Art Studies. 82. No. 1 (16). Moscow, 1983. p. 336

- Lukomsky G. K. Notes from the Artist. Letters from Berlin. Among collectors. 1922. July-August. No.7-8 p. 5

- Lunacharsky A. V. Russian Exhibition in Berlin. // cited in: Lunacharsky A. V. On Fine Art. Moscow, 1967 T. 2. p. 96

- U. L. On the Exhibition of Russian Painting (Impressions of an Ordinary Citizen. On the evening of November 21, 1922. No. 191. // cited in: Lapshin V. P. First Exhibition of Russian Art. Berlin. 1922. Materials for the History of Soviet-German Art Relations. Soviet Art Studies. 82. No. 1 (16). Moscow, 1983. p. 344.

- Finkeldei Bernd. Under the Sign of the Square. Constructivists in Berlin. // Moscow-Berlin /Berlin- Moskou.1900-1950. Moscow, Berlin. Moscow, 1996. p. 160

- Lunacharsky A. V. Russian Exhibition in Berlin. // cited in: Lunacharsky A. V. On Fine Art. Moscow, 1967 T. 2. pp. 94-100

- M. (Mayakovsky V.V) Exhibition of Fine Art from the RSFSR in Berlin. Red Field. 1923. No. 2. p. 25

- Tugendhold Ya. A. Art Exhibition in Berlin. “Russian Art”. 1923. No. 1 p. 102

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Tugendhold Ya. A. Art Day Issues. Izvestia. 1922. December 24. No. 292

- Tugendhold Ya. A. Art Exhibition in Berlin. “Russian Art”. 1923. No. 1. p. 97

- ibid. p. 101

- Tugendhold Ya. A. Art Exhibition in Berlin. “Russian Art”. 1923. No. 1 p. 101.

- Tugendhold Ya. A. Art Exhibition in Berlin. // “Russian Art”. 1923. No. 1. p. 101

- ibid.

- Lunacharsky A. V. Russian Exhibition in Berlin. // cited in: Lunacharsky A. V. On Fine Art. Moscow, 1967 T.2. p. 97

- from “The History of Artistic Life of the USSR. International Ties in the Area of Fine Art. 1917-1940.” Materials and documents. Moscow. 1987. p. 107

- Adkins Helen. Create New Ways of Expression! German Political Art in the 1920s—Model for the USSR // Moscow-Berlin / Berlin-Moskou. 1900-1950. Moscow Berlin. 1996. p. 235

- Zump G. 'Exhibitions of German Art in the Soviet Union in the Mid- 20s and their Evaluation by Soviet Critics.' // “Mutual Ties Between Russian & Soviet Art and German Artistic Culture.” Moscow, 1980. p. 185

- M. (Mayakovsky V. V.) Exhibition of Fine Art from the RSFSR in Berlin. Red Field. 1923. No. 2 p. 25

Photograph

Oil on canvas. 53 × 63 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The portrait was painted during the exhibition in Berlin.

Photograph

Photograph

Oil on canvas. 104 × 88.5 cm

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Oil on canvas. 80 × 80 cm

© Kovalenko Krasnodar Regional Art Museum

© MOMA, New York

Oil on canvas. 52 × 34 cm

© Sukachev Irkutsk Regional Art Museum

Oil on canvas. 120 × 120 cm

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Oil on cardboard mounted on canvas. 42 × 64 cm

Private collection

Oil on canvas. 122 × 124 cm

© Sukachev Irkustsk Regional Art Museum

Oil on canvas. 110.5 × 87.5 cm

© Kaluga Art Museum

Oil on сanvas. Private Collection

Oil on canvas. 89.5 × 62 cm

© Nizhny Tagil Museum of Fine Arts

Oil on canvas. 93.3 × 126 cm

© Mashkov Volgograd Museum of Fine Arts

Ink on paper. 22 × 18 cm

© Kovalenko Krasnodar Regional Art Museum

Oil on canvas. 117 × 154.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 122.3 × 73 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Sketch for the stage decorations for Glinka’s opera “A Life for the Tsar”. Colourwash on carboard. 54.4 × 95.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

1987 reconstruction. Plywood 59 × 69 × 59 cm

© Museum of Personal Collections, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Watercolour, paper. 25 × 34 cm

© Kovalenko Krasnodar Regional Art Museum

Oil on canvas. 80.5 × 70.5 cm

© Vologda Regional Art Gallery

Oil on canvas. 46 × 55 cm

© Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

Oil on canvas. 39.5 × 31 cm

© Nizhny Tagil Museum of Fine Arts

Colourwash, bronze colour, lead pencil on carboard. 47.7 × 64.2 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Xylography on paper. 19.7 × 23.5 cm

© Yaroslavl Art Museum

Screen print, colourwash. Full collection of the works of Vladimir Mayakovsky. V. 4 1937

© Mayakovsky Museum, Moscow

Sketch for a production of the opera “Victory over the Sun”. Carboard, gouache and linocut. 17 × 20.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

LEF. 1923. No. 1. Pp. 61-63

Oil on canvas. 125 × 90 cm

© Central Museum of Contemporary Russian History, Moscow

Brush, quill, ink, watercolour on paper. 36.4 × 44.6 cm

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Linocut. 64 × 41 cm

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Ink, watercolour on paper. 24.3 × 32.5 cm

© Central Museum of Contemporary Russian History, Moscow

Lithography. 40.1 × 31 cm

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Paper, reproduction from lithograph

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

Paper, typographic paints

© Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow