THE PROPYLAEA FROM THE OTHER SIDE

* Alexander Rozhin (born 1946), Art History graduate of Moscow State University. Full member of the Russian Academy of Arts, member of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Arts, Academic Secretary of the Artists’ Union of the USSR (1975-1980), Editor-in-Chief of “Tvorchestvo” magazine (1980-2002), Editor-in-Chief of “Tretyakov Gallery Magazine” (since 2003). Pro-rector for Research of the Surikov Moscow State Academic Art Institute (2006-2014). Awards include the Gold Medal of the Russian Academy of Arts and the Arkady Plastov Award. Author of over 300 publications in Russia and abroad.

The Year of Germany in Russia is no ordinary - no conventional - undertaking. It represents a true continuation of the “affairs of days long gone” - their transition into modern times. The following articles cover almost 200 years of Russo-German relations in the sphere of arts & culture, and special attention is given to the period from the 1920s to today, excluding the tragic events of the Second World War. The aim of this piece is to remind readers of the brighter and more exciting realities of this bilateral partnership, to which this author has been participant and witness.

FRANCISCO INFANTE. Soul of the Crystal. 1961

Acrylic plastic, metal. 30 × 30 × 30 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The majority of my colleagues and I, members of the creative intelligentsia of the USSR, were familiar with the names and works of many renowned Western European artists, including those of West Germany. Of course, East German artists were not only known to us, we also visited exhibitions of their work in Russia, and they had similar opportunities to view our work in East Germany. Our respective Ministries of Culture and creative unions enjoyed even closer ties but we all knew them well, and some of us even fostered personal relationships with our German colleagues such as Willi Sitte, Walter Womacka, Werner Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Otto Nagel, Fritz Cremer, Kathe Kollwitz, Lea Grundig, Bernhard Heisig and Hans-Hendrik Grimmling. At the time, the Artists’ Union of the USSR lead this cultural collaboration with colleagues from other countries. Having close links with East German artists did not exclude us from collaborating with colleagues from West Germany or other western nations, and by the end of the 1970s these relations were beginning to strengthen in earnest, further assisted by the later detente and glasnost - at this point, the Federal Republic of Germany came to lead this cultural rapprochement. The Artists’ Union of the USSR, as one of the most democratic and transparent non-governmental creative organisations, presented counter-initiatives to our foreign peers. And so, the Central House of Artists, under the ownership of the Artists’ Union and the Art Fund of the USSR, started hosting major exhibitions of foreign contemporary art. One of the most unforgettable events was the debut exhibition of works by Western artists from the Deutsche Bank collection, where for the first time Russian viewers saw the works of the British painter Francis Bacon, the French artists Arman and Yves Klein, Lucio Fontana from Italy, Roman Opatka from Poland, Czech artist Stanislav Kolibal and Hungarian Victor Vasarely. It was a genuine revelation after the exhibition that had shaken public consciousness in 1959: the American National Exhibition in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park, where we first saw originals by Andrew Wyeth, Robert Rauschenberg, Grant Wood, Jackson Pollock, Jasper Johns, Mark Rothko and others. Deutsche Bank launched a series of large-scale viewings of eminent artists from around the world and, of course, from East Germany. On the Soviet side, the starting point was a proposal from the Artists’ Union of the USSR, initially suggested by then-First Secretary Tahir Salahov, to begin a non-monetary exchange with similar non-governmental organisations abroad. Among the first contracts for the exchange of delegations, exhibitions and informational materials were agreements made with the Artists’ Unions of West Germany, Finland, Israel and others, as well as with individuals and collectors. And so, from the German side, Peter Ludwig appeared on the Soviet horizon and, later, Gerhard Lenz and others. Deutsche Bank played a significant role on the German side in realising exhibitions and related activities, as did airline company Lufthansa, Dresdner Bank and a number of other financial organisations and industrial corporations, universities and museums, including the Free University of West Berlin, Ruhr University in Bochum, Düsseldorf Art Academy, the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen and the Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museum in Duisburg. The interest was mutual, as evidenced by exhibitions of Russian art in Germany and German art in the Soviet Union and the publication of articles by German art historians and critics in our journals, including pieces by Armin Zweite, Karl Eimermacher, Hannah Weitemeier, Jürgen Harter, Tina Baumeister and Gottfried Bohm. Furthermore, Soviet artists were invited to take part in international events such as the Youth Triennale of Drawing in Nuremberg and the Biennale of Graphic Art in Baden-Baden, both organised by our German colleagues.

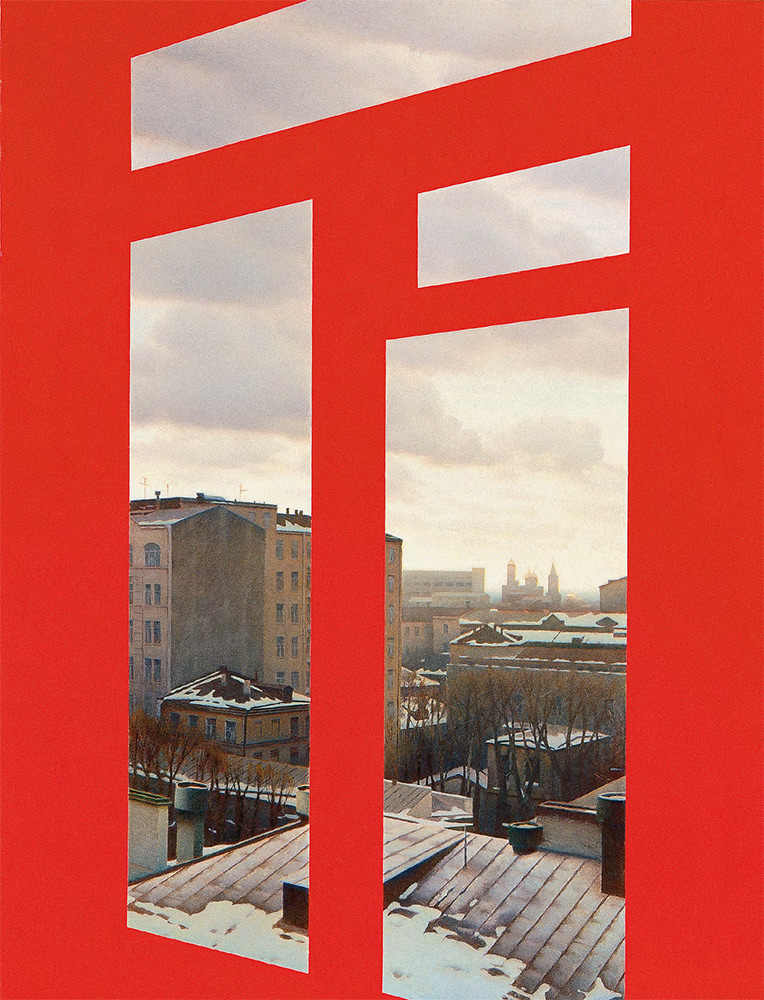

ERIK BULATOV. Moscow Window. 1995

Oil on canvas. 190 × 140 cm

Ekaterina and Vladimir Semenikhin collection, Moscow

Of course, there have been a number of similar breakthrough events at an intergovernmental level, which have aspired to portray the globality of the artefacts and artworks: the “Moscow - Paris / Paris - Moscow” exhibitions of 1981 and the 1996 “Moscow - Berlin / Berlin - Moscow” exhibition in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow marked almost 15 years of extensive exchange of cultural heritage between European nations, dominating the mainstream - as a kind of globalisation. Issues of national identity and internationalisation became more sharply pronounced with the emergence of postmodernism. However, these issues had also existed previously, during antiquity, the Renaissance and Romanticism, when Pushkin had written about them: “he spoke of the coming times when the people, having forgotten their strife, would unite into one family” (1834). Similar ideas occupied the minds of other poets too - thinkers of the Romantic era such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Heinrich Heine, Byron and Adam Mickiewicz.

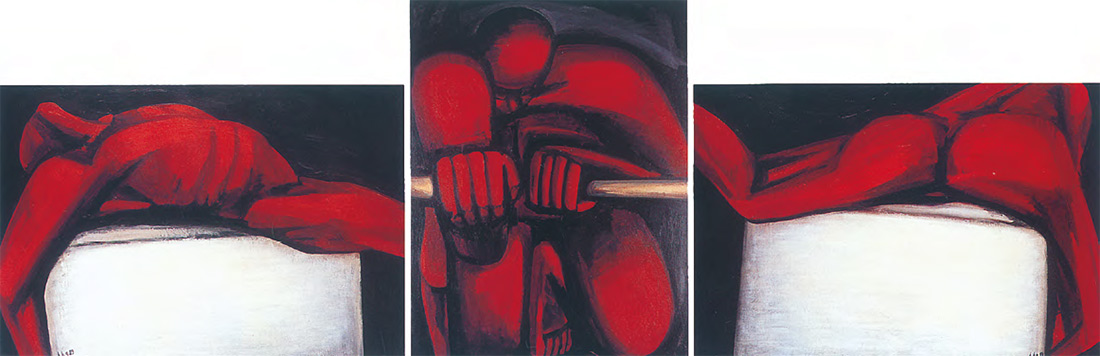

HANS-HENDRIK GRIMMLING. An Oarsman Triptych. 1983

Oil on hardboard. 100 × 150 (2), 150 ×120 cm

Let us return to the second half of the 20th century, to the emergence of new movements and trends: abstract expressionism, photorealism (hyperrealism), performances and happenings, video art, the coexistence of conceptualism and traditional figurative art. These movements and their related styles and trends were in fact represented in the Russian art scene, and accompanied by intense discussions between born-again reformers and orthodox zealots with traditional values. All of this took place amidst foreign artists' personal exhibitions of their own visual, realistic and non-figurative art and its virtual models, including events organised by Roger Somville, Giorgio Morandi, Günther Uecker, Jannis Kounellis, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Gilbert & George, Jean Tinguely, Max Weimer, Rufino Tamayo, Francis Bacon, Salvador Dali and, more recently, Joseph Beuys in MOMA (Moscow Museum of Modern Art) in 2012; Louise Bourgeois and George Baselitz in Garage art gallery; Anselm Kiefer in the Hermitage in St Petersburg; Ilya Kabakov in Moscow's New Tretyakov; Gerhard Richter in the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre in Moscow; and Tadashi Kawamata at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. In their own way, these integrative processes co-opted and reflected the works in the Gerhard Lenz collection shown in 1986 at Moscow's Central House of the Artist.

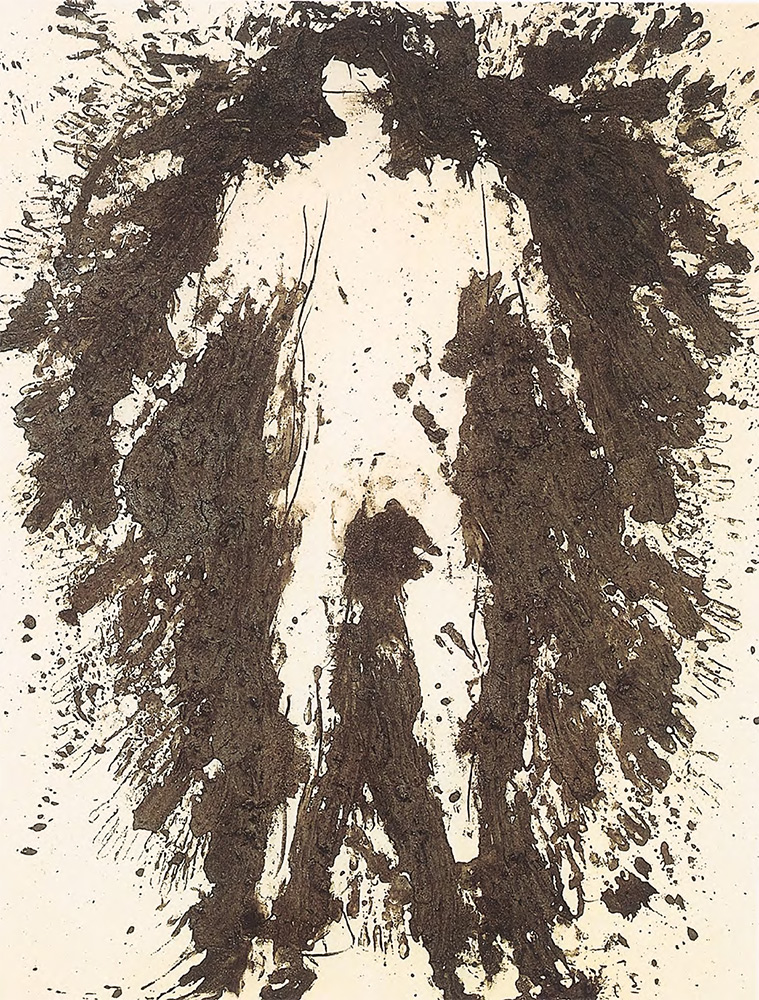

GUENTHER UECKER. Man of Ashes. 1986

Ashes, glue on canvas. 200 × 160 cm

In this regard, one must note Lenz's role in establishing and expanding direct contact between masters of fine art in the East and the West. On his own initiative and using private funds, he often invited many Soviet artists to Germany as well as to his estate at Soil (Austria). He organised discussions and creative meetings between artists from the USSR and Germany and other Western European nations, which allowed for an open dialogue to be initiated between them. I recall the names of only a few of the participants on the Soviet side: Andrey Vasnetsov, Stepan Dudnik, Igor Obrosov, Nikolai Andronov, Pavel Nikonov, Tahir Salahov, Radesh Tordia (Georgia), Oleg Vukolov, Eduard Steinberg, Suhrob Kurbanov (Tajikistan), Nazym Babaev (Azerbaijan), Dace Liela (Latvia), Olga Grechina, Andrey Volkov, Dmitry Nadezhin, the art historians Alexander Morozov, Alexander Kovalev, Vitaly Manin and Oleg Butkevich. They are all representatives of different generations, bearers of various aesthetic traditions and preferences. The unity of a range of ambitions and trends, slogans and manifestos was reflected in their works, which nonetheless allowed them to find a shared language and points in common in their opinions of contemporary and future art in its traditional and avant-garde forms.

If talking about personal perceptions and understanding of modernism in its contemporary form, then, in the opinion of this author, this movement must be thought of as a game of intellectual skill. The main question, then, is to figure out whose rules to follow.

In this regard, we would like to recall a fragment of an interview by the famous French art historian and cultural philosopher Pierre Restany with Sylvain Lecombre, in which he noted that “At the end of the 50s, we experienced the final phase of the country's reconstruction, an economic boom started... The Fourth Republic was, as far as I could tell from the watchtower, experiencing not only an economic and social upturn, but also the oppressive influence of the United States on its politics and economy.

“Both of these factors substantially sped up historic processes, but intellectual and artistic ferment was growing with a speed reminiscent of that at which political agitation normally develops, dragging everything into its maelstrom”. (“Sammlung Lenz Schonberg”. Stuttgart 1989, p. 83)

Restany's view of the situation in France was projected onto the state of affairs and culture of a number of countries in post-war Europe - a process characteristic of both today's situation and the understanding of postmodernism. In general, one may consider that the growth of integration and globalisation has brought about significant change to the cultural life of modern society. This process is without beginning or end, and is complex and contradictory.

Interaction between members of the creative intelligentsia of various countries might not have been so multifaceted and lively without its stimulation by motivated financial institutions and the participation of cultural figures such as Christos Joachimides, Peter Ludwig and Gerhard Lenz, whose contributions and roles cannot be underestimated. It is also necessary to highlight the important part played by international art fairs and exhibitions: the Venice Biennale, Art Basel (Switzerland), FIAC (France), “Documenta” in Kassel, the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, Kunsthalle Düsseldorf and Hamburger Kunsthalle, the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, Lenbachhaus in Munich, the museums in Berlin and Dresden, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, as well as the Russian and Berlin Academies of Arts. Of course, a panoramic view of the current state of the arts in the European community - the function of international organisations such as AIAP, ICOM, AICA, UNESCO and the British Council - also reflects the contradictions of the discourse on contemporary art policy, in which certain transformations occur, and the age-old face-off between ideology and money switches sides. This is, in our opinion, the key problem, the resolution of which is hindered by inappropriate views on the role and aims of the arts in modern society. These issues remain unsolved for the time being.

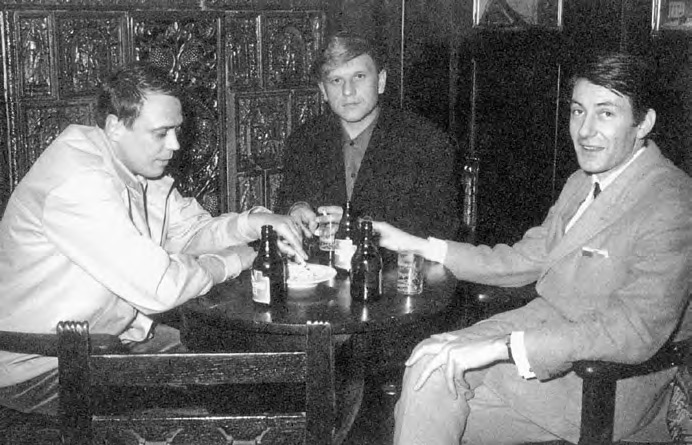

The ZERO Group: from left, Guenter Uecker, Heinz Mack, Otto Piene. 1961

Photo

Borrowing the words of Heinrich Heine, “and even here, in broad daylight, black shadows walk around”. In order for the situation not to resemble a tug-of-war, it is important that we remember the mutual role and responsibility of Germany and Russia in this process, if not as allies, but as partners headed either into the foreseeable future, or to nowhere.

Bronze, granite. 75 × 40 × 35 cm

Oil on canvas. 90 × 95 cm

Oil on canvas. 160 × 200 cm

Photo

Oil on canvas. 110 × 80 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Mixed media on canvas. 70 × 100 cm

Mixed media on hardboard. 175.8 × 174.5 сm

Oil on hardboard. 170 × 274 cm

Photo

Photo paper, black-andwhite printing, wood, hardboard. 145 × 90.5 × 3.7 cm

Glass, metal. 234 × 167 × 336 cm

Installation

Photo