CHOSEN RELATIONSHIPS. The Russian avant-garde as reflected in German art exhibitions

* Hubertus Gassner (born 1950) is an art historian and curator and was, among other things, Director of the Hamburg Kunsthalle from 2006 to 2016. Since 1972, he has continuously worked with the Russian avant-garde as an academic, curator and author and has organised many widely acclaimed exhibitions on the topic.

The brief epoch of the Russian avant-garde, as creatively charged as it was, has successfully established itself in the West - albeit not without confusion and obstacles. The interchange between German and Russian museums, artists and academics at the beginning of the last century did not take off again until the 1970s, with widely acclaimed exhibitions debuting previously unseen works and artists, presenting a differentiated picture of the various directions in art or, as a current show in Cologne’s Museum Ludwig does, taking a courageous look at the topic of originals and fakes.

KAZIMIR MALEVICH. Suprematist Composition. 1915

Oil on canvas. 66.5 × 57 cm

Museum Ludwig, Cologne. Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne

Separating the Wheat from the Chaff

In Memoriam Elbrus Gutnov, Vladimir Kostin, Valentina Kulagina, Alexander Labas, Sergei Luchishkin and Tanya Tretyakova for their friendship and support in the 1970s

“Don’t touch Russian art - This market is flooded with fakes” (“Finger weg von russischer Kunst - dieser Markt ist von Fälschungen verseucht”), warns the alarming title of Christian Herchenröder's article in the “Neue Zürcher Zeitung” on June 30, 2018, addressing the counterfeit scandals relating to Russian avant-garde works that have made headlines throughout the past decade. His sad summary ends on an expectant note: “Several museums, including Cologne's Museum Ludwig, are now examining their own Russian avant-garde collections in art-historical terms. The number of real works that will be left in the end indeed remains to be seen.”[1]

Exhibition view “Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake – Questions, Research, Explanations”. Museum Ludwig, Cologne, 2020

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Köln / Chrysant Scheewe

The exhibition at Cologne's Museum Ludwig, “Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake - Questions, Research, Explanations” (September 26, 2020 until January 3, 2021) presented the initial results of this examination process, which began in 2009, accompanied by a German/English catalogue. The result is shocking. Of the almost 100 paintings from this epoch owned by the museum, 49 paintings were checked for authenticity in terms of art-technology and painting technique. In the wake of the investigation, almost half of these paintings had to be written off as non-authentic or, put more directly, as fakes. And no significantly better outcome can be expected in the case of the additional 50 paintings that have not yet been completely examined. This is an extremely painful loss for the Ludwig collection. At the same time, however, it is a fantastic, courageous first step towards restoring this brief but important and creatively charged artistic epoch to a purer light. This comes in the aftermath of the flood of counterfeits in the Russian avant-garde market and collections over the last 30 years, which has even brought art itself into disrepute.

During the 1980s and 1990s, numerous exhibitions, publications and auctions fuelled an international boom of interest in this artistic epoch. The Russian avant-garde was imbued with the exotic flair of exciting new finds made behind the Iron Curtain, usually accompanied by an adventure story of the find having been discovered, dug out and brought by covert or official means to the West, where they were presented to astonished audiences as priceless objets trouvés. The series of counterfeiting scandals that occurred primarily in Germany and France (Klagenfurt 2000, Tours 2009, Passau 2012/13, Wiesbaden 2013-2018, Ghent 2018) broke this spell and the once glamorous presentations are now giving way to a more sober assessment and sense of disappointment among collectors, auction houses and museums.

KAZIMIR MALEVICH. Supremus No. 38. 1916

Oil on canvas. 102.5 × 67 cm

Museum Ludwig, Cologne. Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne

The causes, which still await resolution, follow from the complex interactions of stakeholders and the roles played by artists, buyers, dealers and dubious expertise in an international network. As far as Cologne's Museum Ludwig is concerned, even after the loss of purported top works, the approximately 600-piece collection of Russian art from the years 1905 to 1930, which the museum has owned since the bequest from Irene Ludwig in 2011, can still be considered one of the most important collections outside of Russia.

Comparable collection highlights can only be found at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam with its unparalleled Malevich collection, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid with its top works, the Thessaloniki State Museum of Modern Art with the Costakis collection, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in New York with the prize pieces it had already purchased in the 1930s.

The Avant-garde Emerges from the Spirit of Freedom

A brief look at the history and reception of the Russian avant-garde in Germany will illustrate the degree to which creative and communicative capital for understanding and mutual inspiration between the two nations is lost when interest in the art of the respective other culture is undermined by counterfeiting scandals. And not only that. Such a survey also reveals the extent to which the dramatic 20th-century social and political events co-determined the relationships between artists in both countries, the mutual reception of art and, ultimately, the development of art itself. The Russian avant-garde is born of the artistic movement “Mir iskusstva” (“World of Art”), itself founded at the end of the 19th century. The movement's symbolistic works, oriented on the one hand towards Western European modern art and on the other hand towards Russian folk art, made an essential contribution to the birth of the Russian avant-garde. The founder and maestro of the Ballets Russes, Sergei Diaghilev, was a member and patron of the movement and organised important exhibitions in Russia and abroad from 1898 until 1906. Diaghilev presented works of the group in 1906 in the Exhibition of Russian Art at the Autumn Salon (“Salon d'Automne”) in Paris. The exhibition was also shown the following year in Berlin - which also happened to be the year European avant-garde was born.

Expressionism, taking shape at the time in Dresden and Berlin, provided little or no inspiration to the younger generation of Russian artists. They looked towards - and often travelled to - Paris, where Cubism was unfolding, and to Italy and its Futurists. During its emergence, the Russian avant-garde united the two directions: the movement-obsessed, dynamic and intensely coloured compositions of the Italian Futurists and the seemingly more static analytical Cubism, which arranged the fragments of the dissected objects of its paintings in a lattice structure and limited its colour palette for the most part to white, grey and brown tones. This synthetic painting style, referred to as Cubo-Futurism, was the basis on which Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov developed their Rayonism. Exhibited for the first time in 1914, Rayonism resolved the object world into abstract ray structures. Cubo-Futurism served as the foundation for Kazimir Malevich's Suprematism with its geometric abstractions, shown for the first time in 1915 in St. Petersburg at the “0,10” exhibition.

In contrast to this majority of artists, the Russians working in Munich developed an expressive painting style, which gave German Expressionism its own flavour. Wassily Kandinsky, Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin, together with the German members of the Der Blaue Reiter artists' group - Paul Klee, Franz Marc, August Macke and others - developed something like a southern German response to the Dresden and Berlin Expressionism of the Die Brücke artists' group. In the 1910s, important meeting points for German and Russian artists arose at the painting school of Anton Azbe, where the Russian professors Igor Grabar and Dmitry Kardovsky led a separate Russian department, and at Marianne von Werefkin's salon on Munich's Giselastrahe. These two locations had been the breeding ground of the 1909 impulse for the foundation of the Neue Künstlerv- ereinigung München, from which Der Blaue Reiter broke away two years later. The external cause of the split was the refusal by the Neue Künstlervereinigung München to show a large abstract composition by Kandinsky in their exhibition.

Three years later, in 1912, as Kandinsky opened his first solo exhibition with abstract paintings in Herwarth Walden's Berlin gallery Der Sturm, it was virulently attacked by the majority of critics, as had been expected. In the following year, on September 20, 1913, Walden held an exhibition close to his gallery with more than 90 artists. In allusion to the “Salon d'Automne” held in Paris since 1903, he named the exhibition the “Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon” (“First German Autumn Salon”). Working through Kandinsky, Walden was also able to invite several artists living in Russia, including David and Vladimir Burliuk, Marc Chagall, Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov. In spite of the great hostility in the daily press, this exhibition, which toured Europe until 1914 and was of such great importance to the artistic avant-garde, meant a breakthrough in Germany for many Russian artists. This success in terms of public attention was, however, eliminated by the outbreak of the First World War shortly thereafter. Because of their Russian origin, Kandinsky, Jawlen- sky and von Werefkin were forced to leave Germany on very short notice. This also put an end to the Blauer Reiter after only three years. Jawlensky emigrated to Switzerland with Marianne von Werefkin; Kandinsky returned to Moscow, where he found himself confronted with the two extremely different tendencies of ‘non-representational' art: the geometric abstraction of Malevich and his followers, artists such as Ivan Kliun, Mikhail Menkov, Lyubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko, Olga Rozanova and Nadezhda Udaltsova, on the one hand, and Vladimir Tat- lin's Culture of Materials on the other. After Kandinsky took over as head of the Institute of Artistic Culture (InChUK) in Moscow and founded the department of Psychophysics at the newly founded State Academy of Artistic Sciences (GAChN), he returned to Germany in the winter of 1921. In 1922, he became the master of the workshop for mural art at Bauhaus, that has been founded by Walter Gropius three years earlier in Weimar. Kandinsky remained a member of Bauhaus until the National Socialists forced its closure in 1933.

Constructivism Revolutionises Art

Kandinsky was not the only Russian artist to settle in Germany after the October Revolution. In the years from 1919 to 1923, Berlin in particular was the new home to hundreds of thousands of Russian emigrants - so many that the Charlottenburg district was sometimes referred to as “Charlottengrad” and Berlin as “Berlinograd”. They brought with them the Russian intelligentsia and all manner of fine artists. This phase is examined in detail by Natalia Avtonomova in her article on the anniversary of “The First Russian Art Exhibition” (“Erste Russische Kunstausstellung”), held at the Berlin Galerie van Diemen in 1922, an event of paramount importance in the creation of awareness and understanding of the Russian avant-garde in the West. In addition to familiar works by Kandinsky, Archipenko and Chagall, works by Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin, Alexandra Exter, Lyubov Popova, Olga Rozanova and Nadezhda Udaltsova, Nathan Altman, Alexander Drevin and Ivan Puni, Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, El Lissitzky as well as Naum Gabo, Antoine Pevsner, Konstantin Medunetzky and Wtadystaw Strzeminski in particular captured the attention of the exhibition's visitors. German artists and art critics, together with a wide audience, “suddenly discovered in the East an entire generation of new artists and ideas” (Hans Richter[2]).

The year 1922 can be seen as the decisive moment in the post-revolutionary development of the Russian avant-garde. For the nascent Constructivists in Russia, “the last picture was painted” in 1922 (Nikolai Tarabukin[3]) - a decision in principle against the panel painting, whether figurative or abstract, which also led to heated controversy in Berlin. “The First Russian Art Exhibition” documented this transition from painting to autonomous visual objects. Shortly after the exhibition opened, Ivan Puni gave his lecture “Contemporary Russian Painting: The Russian Exhibition in Berlin” (“Die gegenwärtige russische Malerei. Die russische Ausstellung in Berlin”) in Berlin's Haus der Künste. Puni declared abstract art, which he himself had previously cultivated as an artist and organiser of exhibitions, to be bankrupt and, along with it, although less radically, Kandinsky's variant of expressive abstraction and the geometrical abstraction of Malevich's Suprematism, upon which the younger Constructivists built. Instead, Puni called for a return to objective-figurative painting, receiving support from art theorist and author Viktor Shklovsky, among others. Altman, Archipenko and Gabo spoke against Puni in favour of an autonomous constructive art (“Objektkunst”). Presumably, the poet Mayakovsky was the only one in this circle to have taken the position of Rodchenko's Constructivists, who especially in this year were fighting for the further development of aimless, autonomous constructive art for the design of everyday commodities. The author Ilya Ehrenburg and the Constructivist El Lissitzky took a moderate position in this heated debate on fundamental principles within the Russian avant-garde by attempting to convey the differences in “Veshsch-Objet-Gegenstand,” their periodical published in 1922 in Berlin. The magazine, which functioned as a platform for the opinions of Russian and international avant-garde artists in order to clarify the respective positions, published only two issues, the differences they had were so irreconcilable.

In response to the “First Russian Art Exhibition” in Berlin, the “First General German Art Exhibition in Soviet Russia” (“Erste Allgemeine Deutsche Kunstausstellung in Sowjet-Russland”) opened in Moscow in October 1924. It featured works from 126 artists, which were later also displayed in Saratov, Perm and Leningrad. Most of all, it was the Verists, such as Otto Dix and George Grosz, and the artists of the New Objectivity that influenced the young Soviet artists of the years to follow, who assembled in the artists' collective OST (Easel Painter's Collective) founded in 1925: Aleksandr Deyneka, Andrei Goncharov, Alexander Labas, Sergei Luchishkin, Yury Pimenov, Konstantin Vialov, Pyotr Williams and others. With its neo-figurative, but nevertheless modern paintings and graphics, this new generation of artists made a decisive artistic contribution to the conscious perception of the Revolution, although they were still far removed from the doctrine of “Socialist Realism” that would be decreed 10 years later.

The precursors to this pseudo-realism that supported the State in the 1930s were rather the Anti-Modernists, who came together in the Association of Fine Artists of Revolutionary Russia (ACHRR). After this group had appeared with an exhibition in Berlin in 1929, the Constructivist association OKTJABR, founded in late 1927 in Moscow, followed suit and organised an extensive exhibition held in 1930 in Berlin and other German cities. Their founding manifesto was composed by the German cultural politician and author Alfred Kurella, who, from 1927 until 1929, had served as head of the Visual Arts department of the People's Commissariat for Education of the RSFSR. In publications and lectures, Kurella, together with Moscow-based Hungarian art critic Ivan Matza, Russian art historian Alexei Fedorov-Davidov and Pavel Novitsky, the director of VKHUTEIN (very comparable to the German Bauhaus), formulated the principles and arguments for this association of revolutionary Constructivists. The association was subdivided into various sections: the architects with Moisei Ginzburg and the Vesnin brothers; the film makers with Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov and Esfir Shub; the photographers with Alexander Rodchenko, Boris Ignatovich, Eleasar Langmann; the photomontage artists with Gustav Klutsis, Valentina Kulagina, Sergei Senkin, Natalia Pinus; the typographers with El Lissitzky, Solomon Telingater, Nikolai Sedelnikov, Elbrus Gutnov and Faik Tagirov as well as the young OKTJABR section led by Vladimir Kostin - to name just a few of the illustrious personalities.

With the mediation of Alfred Kurella, the extensive “OKTJABR” exhibition was opened by the German ASSO (Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists of Germany) in 1930 in Berlin on MQnzstraOe 24. At the same time, 1930/1931, Kurella was working with Berthold Brecht and Walter Benjamin in Berlin on publishing a magazine entitled “Krise und Kritik” (“Crisis and Criticism”), which never appeared. Another member of OKTJABR was a friend of Brecht and Benjamin, author and art theorist Sergei Tretyakov, who also represented societally ‘operative' or ‘interventionist' art with the most modern art-technical methods and media. This is why this last association of Russian Constructivists included only one painter, Aleksandr Deyneka, who, at the time, was working more as a graphic artist than as a painter. The Constructivists of OKTJABR made no secret of their aesthetic roots in the geometrical abstraction of Suprematism. In 1929, as head of the department for Modern Russian Art (19291934), Alexei Fedorov-Davidov organised the last monographic exhibition of Malevich at Moscow's Tretyakov Gallery. The following year, Malevich was held under arrest for two weeks and interrogated, more than anything because of the several months he spent in Germany in 1927, during which he had maintained intensive contacts with the Dessau Bauhaus and artists and architects in Berlin. In Hanover and Berlin, he left behind 70 paintings that had been shown in 1927 at the same time the “Great Berlin Art Exhibition” (“Grossen Berliner Kun- stausstellung”) took place. There, they survived the war, were rediscovered in 1951 and purchased by the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1958.

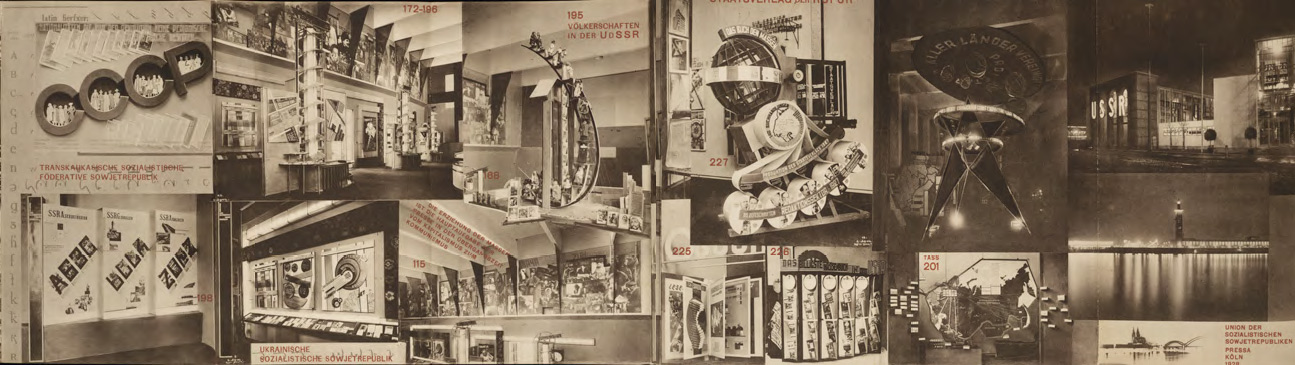

“PRESSA” in Cologne, 1928

Exhibition booklet. Designed by El Lissitsky

OKTJABR members El Lissitzky, Gustav Klutsis and Sergei Senkin attracted much attention at the legendary Cologne exhibition “PRESSA” in 1928 with their giant photomontage frieze and their three-dimensional, partially movable typo-photo installation. The photo and film section of OKTJABR also held its own at the 1929 Stuttgart exhibition “Film und Foto,” which has gone down in the history of photography as a milestone of New Photography, with El Lissitzky responsible for the dynamic-constructive presentation. The photomontage section of OKTJABR once again attracted attention in 1931 in the comprehensive exhibition “Fotomontage” in Berlin's Lichthof at the former Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts). The creative and intellectual leader of the group, Gustav Klutsis, wrote the exhibition catalogue's introductory article “Photomontage in the USSR” (“Fotomontage in der UdSSR”) for this last show. It was to be the last exhibition in which the Russian Constructivists were able to present their concept of an operative interventionist art to the German public. After that, OKTJABR was forced to dissolve: the avant-garde tendencies were no longer tolerated in the Soviet Union in late 1931. The following year saw the decision on the dissolution of all existing independent artist groups and the ordinance creating a central all-unions artists' group, putting a final end to the debates about an artform operating with the techniques of modern art. Just as the Nazi regime had done in Germany, Stalinism made a radical break away from all forms of modern influences in art.

The second half of the 20th century is overshadowed by the Second World War: for decades, trauma and mistrust characterised the relationship between Russia and Germany. To an even greater extent than the First World War, the Second World War buried in the debris the memories of the many fertile contacts between the artists of the two nations in the 1910s and 1920s. The suppression, defamation and repression of the artistic avant-garde in the Soviet Union during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s was another factor that contributed to the complete disappearance of the avant-garde from the public eye.

Delayed Rediscovery

An initial and thorough survey of the epoch of the Russian avant-garde, at the time locked away in the inaccessibility of the East, can be found in “The Great Experiment” by Camilla Gray, an extensive publication that was released in 1962 in London and by publishers DuMont Verlag in Cologne. Gray's idea was also the impulse for an exhibition in London's Hayward Gallery in 1972, “Art in Revolution: Soviet Art and Design since 1917,” which for the first time showed works on loan from Soviet museums as well as from Western private collections and reconstructions such as “Tatlin's Tower.” However, to the surprise of the organisers, shortly before the exhibition opened, the Soviet consignors demanded that the reconstruction of Lissitzky's “Abstract Cabinet” (“Kabinett der Abstrakten”) be closed and the abstract paintings by Malevich removed. After the debut in London, the exhibition was also seen with the title “Art in Revolution. Architecture, Product Design, Painting, Sculpture, Agitation, Theatre and Film in the Soviet Union 1917-1932” (“Kunst in der Revolution. Architektur, Produktgestaltung, Malerei, Plastik, Agitation, Theater, Film in der Sowjetunion 1917-1932”) at the Frankfurt Kunstverein and then in Stuttgart and Cologne. The German version of the exhibition had to make do without the Russian loans that had been withdrawn in London. Eckhart Gillen and I contributed an article to the catalogue about the artists of the group OST (1925-1929), which presented painters still completely unknown in the West, names such as Aleksandr Deyneka, Yury Pimenov, Konstantin Vialov and Pyotr Williams, even though these artists were not represented in the exhibition.

Gillen and I travelled to the Soviet Union in 1971 in order to attempt to organise an exhibition showcasing the entire diverse scope of the Russian avant-garde with loans from Soviet museums. The contacts and discussions began at the Tretyakov Gallery with the then time-honoured director Polikarp Lebedev, who, after all, had published a documentary volume in the 1960s on 20th-century Russian art, with texts giving voice to the avant-garde. The book was, in essence, an abridged version of the comprehensive and still exemplary text collection published by the theoretician of Constructivism and OKTJABR member Ivan Matza in Moscow in 1933. These two publications served as the basis for the documentary volume “Between Revolutionary Art and Socialist Realism” (“Zwischen RevoIutionskunst und Sozialistischem Realismus”), published and commented on by Gillen and myself in 1979. Our negotiations with the museums and the Soviet Ministry of Culture lasted until 1977, when after a long but always respectful preparation phase, the exhibition "Kunst aus der Revolution: Sowjetische Kunst während der Phase der Kollektivierung und Industrialisierung, 1927-1933" (“Art from Revolution: Soviet Art during the Industrialisation and Collectivisation, 1927- 1933”)[1] could open at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin's Hansaviertel district. For the first time in the West, this show presented exclusively loans from Soviet museums, in particular from the State Tretyakov Gallery, the Shchusev State Museum of Architecture and the Lenin State Library of the USSR (now the Russian State Library), all in Moscow, as well as from the Russian Museum in Leningrad. The same can be said of the important exhibition curated by Klaus Gallwitz, also in 1977, at the Stadelsches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt am Main, “Russian Painting 18901917” (“Russische Malerei 1890-1917”). The exhibition was the first time in the western Bundesrepublik that works of the Russian avant-garde from Soviet museums could be shown as they had been in Berlin. Although the works on loan here were exclusively from State collections, the third major exhibition in this year presented works from the private collection of the legendary Greek collector George Costakis, assembled in Moscow since 1946, as “Works from the Costakis Collection: Russian Avant Garde 1910-1930” (“Werke aus der Sammlung Costakis. Russische Avantgarde 1910-1930”), presented at the art museum in Dusseldorf immediately after Costakis left the Soviet.

Art Diplomacy during the Cold War

These three exhibitions represented an initial step towards collaboration between Russian and German museums and exhibition houses. Nevertheless, the cautious, albeit friendly, rapprochement continued to be accompanied by conflict. Thus, for example, on the Russian side, the exhibition's title was listed as “Art from Revolution” (“Kunst aus der Revolution”), whereas we retained our programme-oriented title “Art in Production” (“Kunst in die Produktion”). This difference of opinion resulted not only in two different titles for the exhibition, but also in two different catalogues. The colour pages were printed in a small additional volume with an introductory essay by the deputy director of the State Tretyakov Gallery, Vitali Manin. The cover of this volume bore the title “Art from Revolution” (“Kunst aus der Revolution”) and the essays of the German work group appeared in black and white only in a printed volume of the same format, with the title “Art in Production” (“Kunst in die Produktion”). When official visitors from the Soviet Union, such as Peter A. Abrassimov, the Russian ambassador in East Berlin, came to the show, the volume of German essays had to be hidden under the sales counter. But although small irritations like these were bearable, the next conflict proved rather more difficult. The East Berlin Slavicist Fritz Mierau had written about Mayakovsky's suicide for the catalogue of the exhibition “Mayakovsky - 20 Years of Work” (“Majakovskij - 20 Jahre Arbeit”), organised in 1978 by the curators of the exhibition “Art from Revolution - Art in Production” in partnership with the Mayakovsky Museum in Moscow and which opened in Berlin in February of that year. However, the Russian consul in West Berlin had forbidden us to publish the article, which was nevertheless included in the catalogue. Another political conflict arose the same year in the collaboration for the exhibition “Paris - Moscou,” which, on the Western side, was originally planned to be a triple constellation: “Paris - Moscow - Berlin.” The Soviet side, however, would not tolerate this combination because of the special status of Berlin. Thus, not only were there two catalogues for one and the same 1977 exhibition in Berlin, there were also two separate exhibitions: “Paris - Berlin 1900-1933” opened in 1978 at the Paris Centre Pompidou, with the curatorship led by Werner Spies, followed by “Paris - Moscou 1900-1930” one year later at the same location.

The exhibition “Kazimir Malevich. Works from Soviet Collections” (“Kasimir Malewitsch. Werke aus sowjetischen Sammlungen”) represents a highly contradictory milestone on the longer way to the rapprochement of the various positions, causing much confusion among the participants. All previous exhibitions of the best-known artist of the Russian avant-garde (next to Kandinsky) were required to make do without paintings from the Soviet museums. Then, in 1980, Jürgen Herten, then the director of the Städtische Kunsthalle Dusseldorf, succeeded for the first time in presenting an exhibition on the leading figures of the avant-garde composed exclusively of works almost completely unknown in Germany and originating in the storerooms of the Russian Museum in Leningrad and the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. A bitter note was the stipulation by the Russian consignors that the works on display were not to be supplemented with works from Western museums. Both sides had planned that, after Dusseldorf, the exhibition would move on to the Hamburg Kunsthalle and to the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden Baden. Russian ambassador Vladimir Semyonov, in office in Bonn since 1978 and himself a collector of the more moderate Russian avant-garde, worked to make this tour a reality; the tour had already been publicly announced. This was an unprecedented gesture in bilateral cultural exchange between the two states. Shortly before the end of the first engagement in Dusseldorf, however, the Russian Ministry of Culture declared, to the amazement and rancour of the German partners, that the works had to be brought back to Russia immediately. The general perplexity in the German art world and press regarding this decision remained unresolved for several years, until Vladimir Semyonov explained to Jürgen Harten that, during the course of the Dusseldorf exhibition, the leading party ideologist of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail A. Suslov, had placed an article speaking out against Malevich in “Pravda” in order to bring about the immediate return of the artworks. Even the well-meaning ambassador was powerless against Suslov. Luckily for all those involved, such times have long since receded into history.

In spite of the consternation evident in the German media, this incident didn't stop Harten from holding to the agreement made with the Soviet Ministry of Culture. It provided for a total of five exhibitions of Russian avant-garde works in the Kunsthalle Dusseldorf. In 1982, the Malevich show was followed by the first exhibition of Aleksandr Deyneka in the West with exclusively Russian loans; in parallel, the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg showed a retrospective of Alexander Rodchenko, featuring primarily works from the museums of the USSR. The International Tatlin Symposium took place in 1989 from November 25 to 27 in the Kunsthalle Dusseldorf, with high levels of participation on the part of Russian specialists. The symposium prepared the first retrospective of Tatlin, an artist and adversary of Malevich, which was then presented in 1993 in Dusseldorf. Before that, in 1990, the major exhibition “Pavel Filonov and his School” (“Pawel Filonow und seine Schule”) was presented in Dusseldorf - completing the pantheon of the Russian avant-garde - and was followed in 1997 by the comprehensive exhibition of their great predecessor and model Mikhail Vrubel, which also later moved to the Haus der Kunst in Munich.

New Works, New Friendships

As a counterpoint to these monographic exhibitions, from 1988 until 1992, a substantial German Russian American working group prepared the most comprehensive exhibition on the Russian avant-garde to date. Entitled The Great Utopia ("Die Große Utopie"), the exhibition was shown at the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and, finally, at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Based on existing research, exhibitions and experiences on on such a significant epoch of modern art, the more than 1,000 works were to create nothing less than a mosaic of all directions, tendencies and artistic subgenres within the Russian avant-garde in a great synthesis that occurred, more than anything, because here, for the first time, the Russian side made the storerooms of the countless provincial museums available. These storerooms had been the silent resting places of many works that had been sent there by the artists in the course of self-organisation during the 1920s and had remained virtually unseen since then. The exhibition thus offered the visitor not only a comprehensive survey of the avant-garde but also an overwhelming number of works that had never been seen before, many of which have enriched numerous subsequent exhibitions on various subjects around the world.

The working sessions, which took place in the three countries over the course of three years, resulted in an intensive and spiritual sense of community among the participants, based on mutual understanding and generated many longstanding friendships - an experience that none of the members would want to have missed. If there had once been a fundamentally contradictory position in the argumentative discussions in this group, it now would have to bear a diametrically inverted sign. The participants from the USA highlighted the sociological perspective of the members of the avant-garde and emphasised their socially committed objectives, while the Russian academic art experts defended the absolute autonomy of art against its instrumentalisation for political and societal purposes. And the Central Europeans felt called on to mediate between the two positions, a process which took place in a friendly atmosphere of mutual agreement.

Outlook

In keeping with the ideological principles of the 1977 exhibition “Art in Production,” I have taken the Constructivist approach of an operative, consciousness-raising art that intervenes in life and works with the latest technical means: in individual exhibitions on Gustav Klutsis and Solomon Telingater, in thematic exhibitions on the afterlife of Malevich's “Black Square” in art up to the present or on the images of the “Tired Heroes” (“Müden Helden”) by Ferdinand Hodler, Aleksandr Deyneka and Neo Rauch as well as in two books on the works of Alexander Rodchenko. Given that so many interesting and successful exhibitions on the art of the Russian avant-garde have been shown over the last 50 years in Germany, a comprehensive exhibition and publication on the Constructivist group OKTJABR remains one topic still awaiting attention. “The Great Utopia” made the first step, the 2018 Art Institute of Chicago show “Revoliutsiia! Demonstratiia! Soviet Art Put to the Test” pointed further down this road, as did an exhibition in the Kunsthalle Mannheim in the same year, co-organised by the Tretyakov Gallery, “Constructing the World: Art and Economy 1919-1939” (“Die Konstruktion der Welt. Kunst und Ökonomie 1919-1939”).

The fruitful collaboration between German and Russian museums, academic art experts and artists, which has lasted since the 18th century, stands before a far- reaching future. This future is enhanced by splendid exhibitions as well as objective research projects that increase our knowledge about the diverse world of Russian art. Among the research projects, we find the Cologne exhibition mentioned earlier, “Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake.” Led by the deputy director Rita Kersting and lead restorer Petra Mandt, the specialists have done more than identify a large number of fakes. They are also highlighting the certainty about the inventory of first-rate works that are found to be authentic beyond any doubt and that present the vitality of the art of that period to German and international visitors alike. It is to be hoped that the courageous project of the museum directors in Cologne will inspire many others to follow their example.

Further events that will continue the dialogue have been announced: the exhibition on Russian Impressionism in Potsdam's Museum Barberini; the major exhibition on Romanticism at the Tretyakov Gallery and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in 2021; the reconstruction of the “First Russian Art Exhibition,” 1922, 100 years later by the Staatliche Museen in Berlin; a show planned jointly by the Hamburg Kunsthalle and the St. Petersburg Hermitage (2023/24) on the Russian relationships with the major German Romanticist Caspar David Friedrich - all further milestones on the very special path of German Russian art relations.

- Two editions were released for the exhibition: Kunst aus der Revolution: Sowjetische Kunst während der Phase der Kollektivierung und Industrialisierung, 1927–1933: [ Katalog] / Neue Ges. fur Bildende Kunst Berlin (West) in Zsarb. mit der Staatlichen Tretjakov-Galerie Moskau, UdSSR; [Organisationsleitung Christiane Bauermeister-Paetzel, Eckhart Gillen]. Berlin : Neue Ges. für Bildende Kunst Berlin (West), 1977; Kunst in die Produktion! Sow. Kunst während der Phase der Kollektivierung u. Industrialisierung, 1927-1933 Materialien anäßlich der Ausst. "Kunst aus der Revolution", Akad. Der Künste, Berlin (West), 20. Febr. bis 31 März 1977.

Graphite pencil on paper. 49.6 × 33.4 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Gouache, watercolour, bronze paint on paper. 18.4 × 36.5 cm

Private collection

Oil on canvas. 89 × 71.3 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 53.5 × 53 cm

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (Solomon Guggenheim Foundation, New York)

Oil on canvas. 200 × 300 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 64 × 44 cm

Private collection, Moscow

Photo: Berlinische Galerie, Museum of Modern Art

Photo: Berlinische Galerie. Museum of Modern Art

Mixed media on board. 66.8 × 49 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Carton. 61 × 48.5 × 34.5 cm

Annely Juda's Fine Art Collection, London

Oil on canvas. 120 × 67 cm

© Russian Museum

Oil on canvas. 106.5 × 106.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Photo: Igor Palmin.

© MOMus-Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection, Thessaloniki

nGbK Berlin, 1977

Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. 1981

nGbK Berlin, 1977

Group photo

From left to right: Christian Borngraber, Eckhart Gillen, Tina Bauermeister, Hubertus Gassner, on the right side: two curators/conservators from the Soviet Union

Photo: nGbK Berlin / Jurgen Henschel

Oil on canvas. 260 × 212 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Oil on canvas. 213 × 201 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

nGbK Berlin, 1977

Photo: nGbK Berlin

Artists’ association IZORAM (Fine Art Studios of the Working Youth). The exhibition “Kunst aus der Revolution: Sowjetische Kunst wahrend der Phase der Kollektivierung und Industrialisierung, 1927–1933” (“Art from Revolution: Soviet Art during the Industrialisation and Collectivisation, 1927-1933”)

nGbK Berlin, 1977

Photo: nGbK Berlin

Ink and coloured ink on paper. 32.4 × 19.7 cm

MOMA, NY

Collection of Kunsthalle Düsseldorf

nGbK Berlin, 1978

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Foto: Rudolf Nagel

© Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, Foto: Rudolf Nagel

15.5 × 11.5 cm

15.5 × 11.5 cm