Henry Moore: The Artist in Wartime

Henry Moore (1898-1986) was one of Britain’s greatest sculptors, and yet it was his drawings of Londoners sheltering from the Blitz that made him famous. Between September 1940 and the summer of 1941, at the height of the German bombing raids on London, Moore made more than 300 drawings, mainly of women and children sheltering on the platforms of the London Underground and in its tunnels, as the city was subjected to nightly air raids that killed some 10,000 civilians.

A selection of Moore’s Shelter Drawings was shown at the Hermitage in 2011 in an exhibition, “Blitz and Blockade”, which remembered the German aerial attacks on London in parallel with the beginning of the Siege of Leningrad in 1941. Drawings made by the young architect Alexander Nikolsky that he had sketched in the basements of the Hermitage during the Siege brought home an element of equivalence with Russia’s wartime experience.

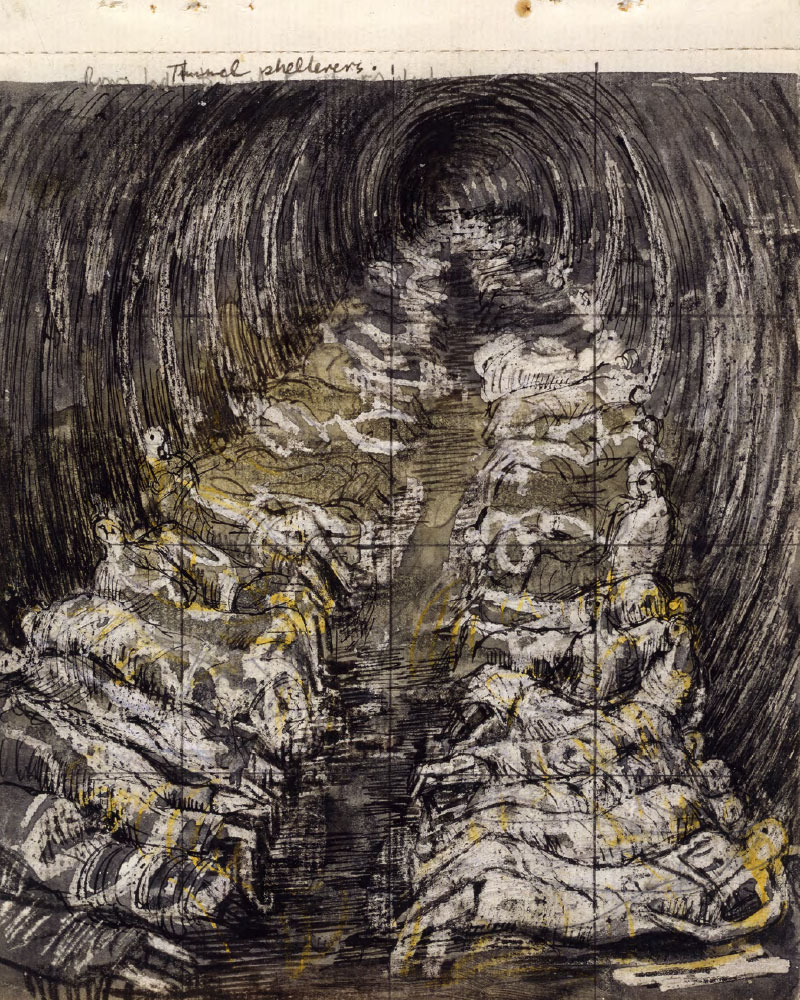

Henry MOORE. Study for “Tube Shelter Perspective: The Liverpool Street Extension”. 1940-1941

Pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour, wash, pen and ink on paper. 20.4 × 16.5 cm

© The Henry Moore Foundation, gift of Irina Moore, 1977

Photograph by Henry Moore Archive. Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation

In the gloom of this strange and terrifying underworld, life and death seem barely distinguishable as figures sprawl awkwardly, contorted in discomfort or slack with exhaustion. Bodies fade away and lose form under blankets. Hues of red, blue and a sickly yellow-green - the toxic colours of life expiring, or rallying - pull bone-white figures from an enveloping shroud of grey, as darkness, fear and damp claustrophobia close in.

At times, as viewers, we create the claustrophobia ourselves as we crouch over sleeping bodies, close enough to feel the breath of a woman whose mouth has fallen open, or to disturb the hollow-eyed, silent vigil of another. And yet, for all their vulnerability, Moore's figures have always been understood as paragons of stoic endurance that transcend the sordid details of individual suffering.

It was this quality that commended them to Kenneth Clark, the director of the National Gallery and chairman of the War Artists Advisory Committee, a government agency set up to employ both young and established artists to record the war effort at home and abroad. Its War Artists Scheme built on an initiative begun in the First World War, when the work of Paul Nash and C.R.W. Nevinson, and other artists returning from the Western Front, prompted the British government to recruit official war artists: the first was Muirhead Bone, despatched to France in May 1916, followed in 1917 by others including Nash and Nevinson, William Orpen and Eric Kennington.

In 1918, responsibility for the scheme transferred to the British War Memorials Committee, which focused on the commissioning of large-scale works for a proposed Hall of Remembrance. The hall itself never materialized, but the project was the catalyst for notable works including “Gassed" (1918-19) by John Singer Sargent, “The Menin Road" (1918) by Paul Nash, and Stanley Spencer's “Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916" (1919), all now in the collections of the Imperial War Museum, London.

Set up in 1939, Clark's War Artists Scheme was far more ambitious, covering almost every aspect of the war effort, on every front. Established under the auspices of the Ministry of Information, the scheme was ostensibly concerned with propaganda, but in reality its scope was much broader. Speaking in a 1944 documentary film, “Out of Chaos", which reported on some of the scheme's efforts in the fields of the visual arts, Clark defined it as speaking “not of the facts but of what the war felt like".[1] By the end of the Second World War, some 6,000 works had been produced by about 400 artists, which were displayed during the course of the conflict in public galleries throughout Britain and the British Empire and Dominions, as well as, importantly, in allied nations such as America and in neutral countries. Henry Moore's Shelter Drawings were among the outstanding works produced under the scheme, along with Paul Nash's “Battle of Britain" (1941), Graham Sutherland's paintings of bombed London, and Stanley Spencer's series depicting shipbuilding on the Clyde.

The Shelter Drawings began as a private project for Moore, following an extended period during which he had struggled to find a subject. A sheet of vignettes entitled “Eighteen Ideas for War Drawings" (1940) gives some sense of his restless mind and eye as he explored the new material the war presented, but he did not settle on any particular direction. As Sebastiano Barassi of the Henry Moore Foundation has written: “Moore was in search of a powerful theme which would enable him to move beyond the mere chronicling of events and towards an empathetic expression of the times."[2]

Just days into the Blitz he found his theme: making his way home to Hampstead one evening, he witnessed the crowds of people camped out on the platforms of the Underground stations as his train passed through. Recalling the experience in 1967, Moore wrote: “I had never seen so many rows of reclining figures and even the holes out of which the trains were coming seemed to me to be like the holes in my sculpture. And there were intimate little touches. Children fast asleep, with trains roaring past only a couple of yards away. People who were obviously strangers to one another forming tight little intimate groups."[3]

These scenes must have gained a more personal resonance when in the first weeks of the air raids, the flat and studio that Moore shared with his wife Irina was damaged by a bomb, prompting their move to Perry Green in Hertfordshire, some 30 miles from London. Here they rented part of a farmhouse called Hoglands, which they would eventually buy along with the surrounding land and

buildings; it would remain Moore's home until the end of his life (and now accommodates the Henry Moore Foundation), with the new environment providing the artist with the space to pursue his interest in outdoor sculpture. As Barassi writes, “Moore was able to experiment with the siting of his work against a harmonious and constantly changing backdrop that shifted with the seasons."[4]

Artistically, the scenes in London's makeshift underground shelters appealed to Moore's most pressing concerns and he seems instinctively to describe them in sculptural terms, though sculpture was out of the question since the war had put materials in short supply. In fact, Moore was well-accustomed to using drawing to explore three-dimensional problems and his interest in volume, texture and weight, and the body's relationship to its environment were not compromised by restrictions on materials. “Sectional lines" placed at intervals on both the transverse and longitudinal axes function rather like contour lines on a map. They were first used by Moore in the 1920s and appear in the Shelter Drawings, where they emphasize volume and three-dimensional shape to suggest a sculptorly preoccupation with the construction of objects in space as opposed to their description in light and shade.

Evidently pleased with his newfound subject, Moore showed the first few drawings to his friend, Kenneth Clark, who duly commissioned him as an official war artist. For Moore, and other artists assigned to the home front, official status may have helped him to work unhindered in a climate of suspicion. Moore was a veteran of the First World War, and too old to serve in the Second, but an unofficial aim of employing artists was to save them from the active service which had claimed the lives of so many only a generation before. Clark cast himself in a paternal role, writing in November 1939 to his friend and long-term correspondent, the art historian Bernard Berenson, that he was busy, having taken on “the interesting but rather heart-breaking job of trying to find work for the thousands of artists who have been left practically penniless by the war. I have been doing this chiefly under the patronage of the Ministry of Labour, and really had to turn into a miniature labour exchange and Shadow Ministry of Fine Arts."[5]

From Moore, the War Artists Advisory Committee would buy 31 large drawings worked up from preliminary drawings in his sketchbooks, and during the war these were regularly on view at the National Gallery, in temporary exhibitions that showcased the fruits of the War Artists Scheme. The permanent collection of the Gallery had been evacuated to Wales when war broke out, leaving its building on Trafalgar Square, at London's physical and spiritual centre, empty: under Clark's leadership it took on a wartime pastoral role, providing Londoners with cultural solace and sustenance regardless of their means. In addition to exhibitions, the Gallery hosted lunchtime concerts which Clark described as a great success, with audiences of up to 1,000 almost every day made up of “people of all sorts who are prepared to give up their lunch in order to escape for a short time out of the ugliness and disorder of the present moment."[6] The concert series had been suggested by the pianist Myra Hess and performers included famous and unknown figures, including musicians from the Royal Air Force. Recitals were held each weekday, even during the Blitz, and were so popular that they continued for some time after the war finished. Writing in a new book published to coincide with the “Bill Brandt/ Henry Moore" exhibition at the Hepworth Wakefield Gallery, West Yorkshire, art historian Nicholas Robbins writes that Moore's reputation was transformed by the reception of his war work, and that “Clark's project of promoting a new national taste for modernism in Britain found perhaps its most public form in the exhibitions of war art held at the National Gallery."[7]

Moore's Shelter Drawings found broad and unprecedented appeal as an expression of solidarity with terrorized Londoners, but for all the particular challenges they presented, for Moore they were principally a development of well-established themes. The pairing of mother and child was already a recurring motif in his work, as was the reclining, specifically female figure. In his first Shelter Drawing, three women with small children on their knees present an opportunity to explore the peculiar dynamics between women drawn to each other through shared circumstances, with each nevertheless absorbed in the care of her own child. Elsewhere, the figures of mother and child take on a monumentality that has quasireligious overtones, and in “Mother and Child among Underground Sleepers" (1941) the woman's protective arm echoes the curved embrace of the tunnel.

In that work, Moore draws a parallel between the watchful mother and the womb-like protection offered by the tunnels to the rows of sleepers nearby. The visual potential of the underground shelters was obvious to Moore, and he found its most extreme expression in the unfinished extension to the Central Line of the Underground at Liverpool Street, which would run eastwards towards the city's docks, a key target of the German bombing. Here, just the tunnel had been dug, and with no platforms or rails installed, people were able to occupy its full width, as in “Tube Shelter Perspective" (1941). As Moore explained, it had “no lines, just a hole, no platform and the tremendous perspective,"[8] a void into which his endless rows of sleepers disappear.

In the stricken East End of the city, Liverpool Street station became a refuge for many thousands of Londoners displaced by heavy night bombing in September 1940, and for Moore it became a favourite site to visit, observe, and take notes. Though Moore's drawings often suggest an uncomfortable proximity to his subjects, he carefully avoided intrusive or insensitive behaviour. Though he spent nights in the shelters, he drew very little while he was there and preferred to make extensive notes that he could work up the next day, explaining: “A note like ‘two people sleeping under one blanket' would be enough of a reminder to enable me to make a sketch next day."[9]

This enforced delay before he began composing his drawings may have introduced the distance necessary to accord the particular dignity that is so characteristic of his subjects. Even so, Moore's transformation of the shelterers into timeless symbols of strength and courage was not accidental, and at the time Moore described them as “like the chorus in a Greek drama telling us about the violence we don't actually witness".[10]

Moore had rejected classicism earlier in his career, and in 1930 he urged the “removal of the Greek spectacles from the eyes of the modern sculptor".[11] That the Shelter Drawings prompted him to think in terms of Greek drama suggests that he had come to accept classicism as a means by which he might dignify his subjects. But just as the solid, resolutely three-dimensional forms of his mother-and-child pairings introduce timeless monumentality to the Shelter Drawings, they also highlight Moore's engagement with the prevailing artistic trends of the day. As early as the mid-1920s, Moore's work showed the influence of Matisse and Picasso, and his abstracted treatments of the body from the 1930s draw on cubist methods. The Shelter Drawings continue that dialogue with Picasso, and Moore's treatment of the female form quite clearly resembles Picasso's approach to similar subjects in works like "La Source” (1921).

Picasso's abandonment of Cubism from 1917 onwards was heavily criticized at the time as a cowardly retreat from the radicalism of his pre-war work. But in truth, his interest in more conventional modes of representation was part of a more general “Return to Order" that took hold in the aftermath of the First World War. Through the 1920s and until around 1950, artists who had been part of the avant-garde of the early 20th century began to draw on the language of permanence, universality, stability and ideal beauty codified within the classical lexicon.

Moore's own engagement with classicism took flight during the war. In the Shelter Drawings he developed a new strand to his interest in the reclining figure, turning the apparent obstacle of figures swathed in clothes and blankets into an opportunity to investigate the draped figure. Influenced by Surrealism, Moore had already begun to explore the dramatic potential of partially obscured forms in the 1930s, using black, in particular, to lend mystery to figures whose form can never fully be revealed.

The Shelter Drawings provided Moore with pause to consider the effect of draperies on a figure, which he found could reveal rather than obscure form, while also granting access to a visual language rooted in the antique and redolent of universal notions of nobility, thus drawing parallels between Londoners sheltering from the Blitz and the draped reclining figures of Ancient Greece.

In December 1942 the British illustrated magazine “Lilli- put" published a selection of Moore's Shelter Drawings alongside photographs of the same subject taken by Bill Brandt (1904-1983). The feature occasioned a meeting between the two artists, and Brandt photographed Moore in his studio where he chose a selection of Shelter Drawings to be reproduced alongside his photographs in a 10-page spread. The idea was an inspired one, demonstrating as it did not the superiority of photography over drawing, but the peculiarities of each medium. Both Brandt and Moore pictured the unfinished tunnel at Liverpool Street, but Moore's rows of sleeping figures contrast with Brandt's chaotic sea of bodies, obscured by clothes. Moore's figures are never quite portraits and the faces, often ghostly, are always indistinct, a decision that can seem like a mark of respect when compared to Brandt's sympathetic but rather intrusive portraits of sleeping women.

In fact, the juxtaposition of photographs and drawings shows a remarkable degree of congruence between the two sets of images, and Martina Droth, co-curator of “Bill Brandt/Henry Moore" notes that both “strike a darkly surreal note. Scenes of sleep rather than death, these claustrophobic pictures nevertheless carry the echoes of civilian casualties and the horrors of battlefields."[12] Though the immediacy of Brandt's photographs draws attention to individual plight in contrast to Moore's more timeless depictions, the “Lilliput" feature succeeds in reinforcing the common ground between them, and the pictures work together to strengthen and enhance each other's observations that, as Droth writes, “the people are stoic, the classes are united, their experience is collective, their suffering is universal."[13]

Looking at Moore's drawings next to Brandt's photographs helps to elucidate exactly how Moore managed to successfully avoid idealizing or romanticizing what he saw. Very rarely, as in his “Woman Eating a Sandwich" (1941), Moore discloses individual anguish. However, even in this case, where fear and sadness, and perhaps pain are gouged into the woman's face, we are seeing a type rather than an individual. In its exaggerated expression of grief, her face is a mask inspired perhaps by the non-western sculptures to which Moore had turned for inspiration in the 1920s.

Moore's drawing technique - a method he called “wax resist" - also proved important, and though it was one he had developed before the war it really came into its own for the Shelter Drawings. The technique relies on the incompatibility of watercolour and wax, and Moore describes how using “a light-coloured or even a white wax crayon, then a dark depth of background can easily be produced by painting with dark watercolour over the whole sheet."[14] Once the watercolour was dry, Moore would reinforce lines with India ink, and often used pencils and coloured crayons, chalk and wax, building up a surface that is thick with texture and tone, and evokes the filthy underground air. Sometimes Moore would scrape back the wax crayon in order to apply a layer of ink, and the effect is at times almost archaeological, or at least spectral, as pallid, waxy figures seem to need clawing back into view.

Moore only worked on the Shelter Drawings for a year, and when the government began to convert the London Underground into official air raid shelters equipped with canteens and bunks he embarked on a new subterranean project, also commissioned by the War Artists Advisory Committee, drawing coalminers at Wheldale Colliery in Yorkshire in the part of England where the artist was born (Moore's father had worked in the same mine).

The imaginative possibilities of life underground preoccupied him even while he was ostensibly above ground. In “London Skyline" (1940-1941), from the First Shelter Sketchbook, an apocalyptic sky glows red, and though the familiar silhouettes of buildings are discernible, the picture is dominated by a devastated landscape that seems to be a kind of No Man's Land, neither entirely under, nor entirely above ground. Figures sit in an underground cave, and with large, bone-like forms suggest some barren, prehistoric landscape.

In the same sketchbook, Moore took this imaginary landscape still further, a faceless white head smashed open like a bombed building to reveal cracked plaster and crumbling bricks inside. This fascination with the new, melancholy landscape that had been created by nightly bombing raids would produce some of the Second World War's most haunting works of art: Moore's drawings echo the psychological landscapes made by painters such as John Minton and Graham Sutherland, and later by the novelist Rose Macaulay, whose 1950 novel “The World My Wilderness" appropriates bombed London as a metaphor for its heroine's troubled mind.

For Moore, the Shelter Drawings would provide a stimulus for much that he would go on to create, including the sculpture that would define the rest of his artistic career. His first sculpture following the Shelter Drawings was a “Madonna and Child" (1943-1944), carved in brown Hornton stone for the church of St. Matthew's, Northampton and very clearly related to the Shelter Drawings in the modelling of the faces and the attention to the body as revealed through clothes. The subterranean world of the Shelter Drawings would also provide inspiration for a series of drawings Moore made in 1944-1945 to accompany the publication of a radio play, “The Rescue", based on Homer's “Odyssey", written by Edward Sackville-West that was first broadcast in 1943. In that work the tunnel at Liverpool Street is reincarnated as the Naiad's Cave, an exhausted shelterer as a sleeping Odysseus, in early echoes of scenes that would continue to resonate for the rest of Moore's career.

As the conflict drew to a close, Moore's re-engagement with sculpture naturally accelerated. “Perhaps now that the war is completely over, the isolated, cut-off feeling we've all had, particularly here in England, may quickly go," he recalled at the time. “Though I myself think that I have been particularly lucky throughout the war. Happiest thing of all is that I have been able to go on working all through - although not all the time at exactly what I would have liked - that is I've not been free to give the majority (and proper proportions) of my time to my real work of sculpture. But that's no longer so."[15] His reputation, too, buoyed by the Shelter Drawings, was increasing incrementally outside his native land: a solo show in America in 1943, at the Buchholz Gallery, New York, was followed by his first major international retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art there three years later. The period of relative inward-looking that the war had brought was over: the acclaim that the wider world would accord him so generously in the remaining four decades of his life had begun.

“Bill BrandtlHenry Moore" is at Hepworth Wakefield to 1 November 2020, then Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, Norwich (22 November to 28 February 2021) and Yale Center for British Art, USA (15 April- 18 July 2021). The accompanying book is published by Yale University Press.

- Kenneth Clark speaking about the War Artists project in the 1944 documentary “Out of Chaos", directed by Jill Craigie. https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-out-of- chaos-1944-online

- Barassi, Sebastiano. ‘To Look More Intensely: Henry Moore and Drawing’//“Henry Moore Drawings: The Art of Seeing". Henry Moore Foundation, 2019, published on the occasion of the exhibition “Henry Moore Drawings: The Art of Seeing", Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green. P. 16.

- “Henry Moore. Shelter Sketchbook". Marlborough Fine Art and Rembrandt Verlag, London and Berlin, 1967. N.p. Quoted in “Henry Moore Drawings: The Art of Seeing". P. 16.

- Barassi, Sebastiano. “Nature and Inspiration", published on the occasion of the exhibition “Henry Moore at Houghton Hall: Nature and Inspiration", in collaboration with the Henry Moore Foundation May 1-September 29 2019. Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green. P. 20.

- Kenneth Clark in “My Dear BB...: The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Kenneth Clark, 1925-1959", edited and annotated by Robert Cumming. Yale University Press, London/New Haven, 2015. P. 233.

- Ibid. P. 234.

- Robbins, Nicholas. ‘Exhibiting Art in Wartime’//“Bill Brandt/Henry Moore". Yale University Press, London/ New Haven, 2020. P. 98. Hereinafter - Brandt/ Moore.

- Wilkinson, A.G. “The Drawings of Henry Moore". London, Tate Gallery (with Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto), 1977. P. 32.

- “Henry Moore. Shelter Sketchbook", quoted in “Henry Moore Drawings: The Art of Seeing". P. 17.

- “Henry Moore. Shelter Sketchbook", quoted in “Places of the Mind: British Watercolour Landscapes 1850-1950", edited by Kim Sloan, British Museum, 2017. P. 166.

- Moore quoted in “The Mythic Method: Classicism in British Art 1920-1950". Published to coincide with the exhibition “The Mythic Method" at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, October 22 2016-February 19 2017. Pallant House Gallery, 2016. P. 34.

- Martina Droth, in Brandt/Moore. P. 18.

- Ibid.

- James, Philip. “Henry Moore on Sculpture". MacDonald, London, 1966. P. 218. Quoted in “Henry Moore Drawings: The Art of Seeing". P. 14.

- Henry Moore, quoted in Henry J. Seldis, “Henry Moore in America". Phaidon, London; Praeger, New York, 1973. P. 65.

Modern archival-toned gelatin silver print from original 1943 negative. 25.7 × 25.4 cm. National Portrait Gallery, London, purchased 2004

© Lee Miller Archives, England 2020. All rights reserved: www.leemiller.co.uk

Pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour, wash, pen and ink, conté crayon on cream lightweight paper. 20.4 × 16.5 cm

© The Henry Moore Foundation, gift of Irina Moore, 1977

Gouache, ink, watercolour and chalk on paper. 27.9 × 38.1 cm

© Imperial War Museum, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Gouache, ink, watercolour and crayon on paper. 48.3 × 38.1 cm

© Tate Gallery, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Watercolour, gouache, ink and chalk on paper. 27.9 × 38.1 cm

© Tate Gallery, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on cream medium-weight wove paper. 27.4 × 37.6 cm

© The Henry Moore Foundation, gift of the artist, 1977

Photograph: The Henry Moore Foundation archive. Signature: pen and ink l.r. Moore/40. Inscription: pencil u.l. searchlights; u.c. Flashes from ground; gunshells bursting like stars; u.r. Night & day - contrast; u.c.l. devastated houses; bomb crater; u.c.r. contrast of opposites; contrast of peaceful normal with sudden devastation; c.l. disintegration of farm machine; fire at night; c. Haystack & airplane; Nightmare; c.r. contrast of opposites; Burning cows; l.c.l. spotters on buildings; barbed wire; l.c.r. Cows & Bombers; Bombs bursting at sea

Graphite, ink, watercolour and crayon on paper. 38 × 56.8 cm

© Tate Gallery, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Graphite, ink, watercolour and crayon on paper. 38 × 56.8 cm

© Tate Gallery, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Watercolour, gouache, ink and chalk on paper. 48.3 × 43.2 cm

© Tate Gallery, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Graphite, ink, gouache and wax on paper. 38.1 × 55.9 cm

© Tate Gallery, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Ink, watercolour, crayon and gouache on paper. 41.9 × 38.1 cm

© Tate Gallery, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Graphite, ink, wax and watercolour on paper. 48.3 × 43.8 cm

© Tate Gallery, London. Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee, 1946

Gelatin silver print. 22.9 × 19.4 cm

© Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York

© Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour, wash, pen and ink on cream lightweight wove paper. 18.1 × 16 cm

© The British Museum, London, bequeathed by Lady Clark

Gelatin silver print. 22.8 × 19.6 cm

© Hyman Collection, London

© Bill Brandt/Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour, wash, pen and ink on paper. 33.7 × 54.6 cm

© Hepworth Wakefield (Wakefield City Art Gallery). Presented by the War Artists' Advisory Committee, 1947

Pencil, wax crayoncoloured crayon, watercolour, wash, pen and ink on paper

© The Henry Moore Foundation

Photograph: Michel Muller. Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation

Hornton stone. Height - 150 cm. St. Matthew’s Church, Northampton, gift of Canon J. Rowden Hussey. Photograph by Henry Moore Archive. Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation

Pencil, wax crayon, charcoal, wash on paper. 52.3 × 44.9 cm. Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia. Photograph by Marcus Leith

© The Henry Moore Foundation