Ars vs Bellum | World War I. 1914-1918. The Metronome of Memory

The “phenomenon of war” in 20 th century art as it emerged from World War I - a brief cultural resume, drawn from both sides of the conflict.

Kuzma PETROV-VODKIN. The Virgin of Tenderness towards Evil Hearts. 1914-1915

Oil on canvas. 100.2 × 110 cm. © Russian Museum

The 20th century seems somehow to have been late in beginning: in reality, it surely started in 1914, when the world of la Belle Époque came to an end. It calls to mind the lines of Anna Akhmatova's “Poem without a Hero":

"So along the legendary quay

Approached, not what the calendars say,

But the real Twentieth Century”

It was in the First World War that the foundations of Post-Modernism, that movement which finally took shape after World War Two, were surely laid. As one cultural era was replaced by another, a terrible wave of death engulfed the continent of Europe, like some beast- god Moloch, some Saturn devouring his children...

As new means of mass destruction appeared, the sheer choice of ways of killing multiplied: suddenly people came to be seen as masses rather than as individuals.

Aviation became a fighting force, chemical weapons were used for the first time, tanks appeared in 1916 on the war fronts of Europe.

Fine art “grew heated" as it tried on a “new mask of death", as the famous Russian art criticAndréi Tolstoy would describe the gas mask. The “softness" of Impressionism, of the Post-Impressionism and Pointillism that followed, was replaced by the harsh cruelty of Expressionism. The resulting sense of apocalypse, of universal tragedy, gave rise to an art of fear - a terrifying art with an anti-military direction, found in a new kind of work: Pavel Filonov's “The German War", 1915; Franz Rou- baud's “Dante and Virgil in the Trenches", 1915; Alexander Shevchenko's “Rayonist Composition", 1914; Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin's “In the Line of Fire (Attack)", 1916, and “The Virgin of Tenderness towards Evil Hearts", 19141915; Mark Chagall's “Wounded Soldier", 1914, and “War", 1915; as well as in the graphic sheets of Ivan Vladimirov and Nikolai Samokish.

The “Amazons of the Avant-garde" were caught up in the frenzy, too: in 1914, Natalia Goncharova created her lithographic series “Mystical Images of War", Olga Rozanova her cycle “War".

The concept of “visual agitation", poster art, reached Russia early on. The traditional form of the lubok, the cheap popular print with its slogans and stories, proved popular with amateur and professional artists alike: among those who created military posters were Nicholas Roerich and Kazimir Malevich, the brothers Viktor and Apollinary Vasnetsov, Konstantin Korovin and Leonid Pasternak.

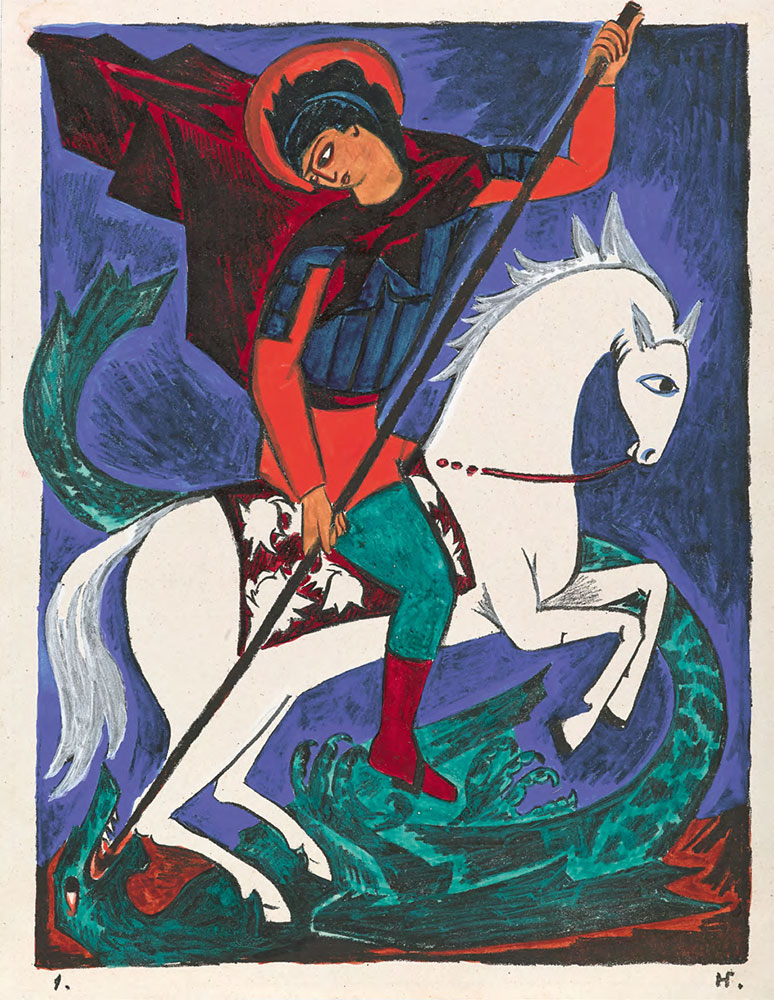

Natalia GONCHAROVA. St. George. 1914

Sheet from the album “Mystical Images of War”

Painted lithograph. 32.5 × 24.9 cm. © Tretyakov Gallery

Artists organized charity exhibitions and auctions to raise funds for the soldiers at the front. Painters even became absorbed in new aspects of the process of war: Konstantin Korovin worked with camouflage and colour-masking at Russian army headquarters.

Waves of anti-war sentiment appeared in the aftermath of war, seen in the German army in the work of Otto Dix (“War Cripples", 1920) and Max Beckmann (“Hell", 1919). In the 1930s, both artists would feature among Hitler's “degenerate" artists, alongside Georg Grosz, whose 1919 series of satirical drawings “Gott mit Uns" (God with Us) would be confiscated by the newly established German republic.

Harmony was replaced by disharmony, the absurdity of human existence revealing itself in images of spiritual and physical deformity.

If, at the beginning of the 20th century, European art had brought together artists from different nations to explore new directions in art collaboratively, the outbreak of war saw that internal unity discarded. In such a way, the “Blaue Reiter" (Blue Rider) association that arose in Munich - “one of the most stellar and impetuous, daring and short-lived artistic groups", in one critical description[2] - disintegrated: some of its members, like Alexei Yavlensky, Marianne Werefkin and Wassily Kandinsky left Germany, others, like Franz Mark and the volunteer soldier August Mack, would die in the war... For the German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, World War One ended in horrific nervous breakdown.

The fate of those who served in the French army was no less difficult, its list of casualties in conflict long.André Derain escaped death only by a miracle; George Braque was seriously wounded, Osip Zadkin, who served in the Russian military contingent in France, poisoned by gas. Guillaume Apollinaire's involvement in the war was brought to an end by shrapnel wounds to his head, from which he would never fully recover.

Upon his return to Paris, Apollinaire would publish his collection “Calligrammes. Poems of Peace and War. 1913-1916". The artist Fernand Leger took part in fighting near Verdun; the Cubist André Mare fought at Plessis-de-Roye; the poet and playwright Jean Cocteau worked as a medical orderly. The painter Moses Kisling, from the Foreign Legion, was wounded on the Somme, in the same battle in which André Masson, that early Cubist who would later turn to Surrealism, sustained serious chest injuries.

The British writer and critic J.R.R. Tolkien, the future author of the “Lord of the Rings" and other fantasy classics, went to the western front in 1915, serving in 1916 as a liaison officer at the Somme, the largest and bloodiest battle of World War I, in which more than one million soldiers were killed and wounded. Serving in the German army, Otto Dix (“Self-portrait as Mars", 1915), that future representative of Kulturbolschewismus and “degenerate" art, fought in the trenches on the opposite side.

The Dadaist and Surrealist-to-be Max Ernst, who was drafted into the army in 1914, would write in his autobiography: “On August 1 1914, M.E. died. He was reborn on November 11 1918." The British artist Paul Nash fought in the war, creating in 1918-1919 a series of works devoted to the Battle of Ypres. The future Nobel laureate Ernest Hemingway received his baptism of fire on the Italian front. His no less famous compatriot Walt Disney, who signed up as a volunteer, as well as the English writer Somerset Maugham became ambulance drivers.

Britain's eminent senior man of letters, Rudyard Kipling, who had won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907, that figure whose work had extolled the Britain Empire's past wars, was engaged with the work of the Red Cross: he was devastated when his son, John, died in combat in 1915. Fighting in the Austro-Hungarian army, Jaroslav Hasek drew on his wartime experience for his “The Good Soldier Švejk".

Mankind experienced the cruelty of bloody conflict, for which a new pictorial, plastic, poetic and musical language would be required - the language that would come to be spoken by the post-war “Lost Generation", those figures disoriented by their experience as survivors.

This new language emerged from the fields of the First World War, it was mastered by those who fought in so many different capacities: the “hussar poets" like Nikolai Gumilev and Nikolai Tikhonov, or the artilleryman Valentin Kataev; the machine-gunner Mikhail Zoshchenko, warrant officer engineer Vsevolod Rozhdestvensky or artillerist Vitaly Bianki, the reserve commander Alexander Kuprin; medical orderlies Konstantin Paustovsky and Alexander Vertinsky, field doctor Vikenty Veresaev, or the nurse Demian Bedny; war correspondents like Mikhail Prishvin, Valery Bryusov, Alexei Tolstoy, Sergei Gorodetsky and Ilya Zdanevich.

That classic of Belarusian literature, Yanka Kupa- la, served in the road construction detachment of the Warsaw Military District Transportation Division. The artist Georgy Yakulov - a veteran of the Russo-Japanese war - sustained serious wounds. Writers Mikhail Bulgakov and Sasha Cherny worked in front-line hospitals. Mikhail Larionov was called up from the reserves. The painter Vasily Shukhaev fought on the Riga Front. The writers and artists Viktor Shklovsky, Anatoly Mariengof, Kazimir Malevich, Pyotr Konchalovsky, Velimir Khlebnikov, Nikolai Milioti, Pavel Filonov, Nikolai Burliuk were all mobilized. The young artists Wladimir Burliuk and Nikolai Le Dantu died in conflict.

The great literature of the 20th century, the literature of World War I, was born - with its de-romanticization of existence, dehumanization of society, degradation of human values: a literature of war.

Alongside all that appeared the romanticized friendship and brotherhood of war camaraderie, of compassion and love aestheticized in a new literature: Ernest Hemingway's “A Farewell to Arms", Mikhail Sholokhov's “And Quiet Flows the Don", Erich Maria Remarque's “All Quiet on the Western Front" and “Three Comrades". Henri Bar- busse, invalided out of the army more than once, wrote his famous anti-war novel “Under Fire", for which he received the Prix Goncourt. In the next generation came Britain's Richard Aldington with his “Death of a Hero" and “All Men Are Enemies", Russia's Alexei Tolstoy with “The Road to Calvary", and Vienna's Stefan Zweig with “Conscience Contre Violence" (The Right to Heresy).

At the outset of World War I, Alexander Scriabin gave charity concerts for the front: in the feast of sound and colour that is his “Prometheus" (1908-1910) his contemporaries seemed to catch the rhythms of impending world cataclysm. Before war broke out, composers were writing marches, among them the 1912 “Farewell of Slavianka" by trumpeter Vasily Agapkin, that melody that would become a lasting symbol of Russia.

But what that protracted war demanded was requiems. “Musical pacifism" emerged during World War One, as composers searched for new ways to express the inhumanity of suffering and the humanity of compassion, attempting to convey the beating of the ashes of the innocent fallen: Claude Debussy with his “Nodl des en- fants qui n'ont plus de maison", 1915; Maurice Ravel, who drove a truck between the front line and the rear, with his “Le Tombeau de Couperin", 1914-17, and Max Reger beginning his “Requiem" in 1915, foreseeing the outcome of the war. Hans Eisler completed his oratorio “Oratorium gegen den Krieg" (Against War) and later “Epitaph auf ei- nen in der Flandernschlacht Gefallenen" (Epitaph at the Tomb of the Dead in Flanders).

By the end of that conflict, Alban Berg and Anton Webern of the New Vienna School were pacifists by conviction. Berg expressed his hatred of the barracks in his opera “Wozzeck", already in the style of Expressionism. Sergei Rachmaninoff's response to the war came with his immortal “Vespers" of 1915. Igor Stravinsky wrote “The Soldier's Tale" in 1918, while that classic of British music, Ralph Vaughan Williams, remembered his own wartime experiences in his “Pastoral Symphony", from 1922.

Among those who fell in World War One there were no doubt many gifted - very likely brilliant, indeed - musicians, writers and artists and performers. Those who survived were forever burned by the flame of war. When Nikolai Gumilyov found out that Alexander Blok might be sent to the front, how succinct was his response to Anna Akhmatova: “That would be tantamount to frying nightingales."

And how eloquent that universal appeal, made in 1915 by Zinaida Gippius, that poet who lived on from her Silver Age glory to see the end of World War Two:

“At the last hour, in darkness, fire,

Let the heart never forget:

No excuse for war!

Forever and never, ‘No!'"

GEORGY IVANOV

In 1913, still in bliss not understanding

The future that awaited us,

Our champagne glasses raised at toast’s demanding,

The New Year thus we met with cheerful fuss.

How old we have become! The years have glided,

The years have glided - and we missed them as they passed...

But yet this free and deathly air’s abided

And still, I’m sure, our recollections hold them fast -

That winter’s happiness and wine and roses.

And so we must through leaden gloom,

As fate to deadened eyes exposes,

Behold a lost world in its tomb.

Translation by Rupert Moreton

VELIMIR KHLEBNIKOV

War in a Mousetrap

Anyway, young men are cheaper nowadays, no?

Dirt-cheap, slop-cheap, coal-chute-cheap!

Pale apparition, scything our man-crop,

sinews all sunburnt, be proud of your work!

“Young men dying, young men dead...”

1919

Translated by Paul Schmidt, 1989

VLADIMIR MAYAKOVSKY

You!

You, wallowing through orgy after orgy

owning a bathroom and a warm snug toilet!

How dare you read about awards of St. George

from newspaper columns with your blinkers oily!?

Early 1915

Translated by Dorian Rottenberg

WILFRED OWEN

Anthem for Doomed Youth

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

- Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs, -

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Published in 1917

SIEGFRIED SASSOON

Dead Musicians

-

From you, Beethoven, Bach, Mozart,

The substance of my dreams took fire.

You built cathedrals in my heart,

And lit my pinnacled desire.

You were the ardour and the bright

Procession of my thoughts toward prayer.

You were the wrath of storm, the light

On distant citadels aflare. -

Great names, I cannot find you now

In these loud years of youth that strives

Through doom toward peace: upon my brow

I wear a wreath of banished lives.

You have no part with lads who fought

And laughed and suffered at my side.

Your fugues and symphonies have brought

No memory of my friends who died...

GUILLAUME APOLLINAIRE

A la memoire du plus ancien de mes camarades Rene Dalize mort au champ d’honneur le 7 mai 1917

On ne peut rien dire

Rien

de ce qui se passe

Mais on change de Secteur

Ah ! voyageur egare

Pas de lettres

Mais I’espoir

Mais un journal

Le glaive antique de la Marseillaise de Rude

S’est change en constellation

Il combat pour nous au ciel

Mais cela signifie surtout

Qu’il faut etre de ce temps

Pas de glaive antique

Pas de Glaive

Mais l’Espoir

ALAN SEEGER

I Have a Rendezvous with Death

I have a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple-blossoms fill the air –

I have a rendezvous with Death

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

It may be he shall take my hand

And lead me into his dark land

And close my eyes and quench my breath -

It may be I shall pass him still.

I have a rendezvous with Death

On some scarred slope of battered hill,

When Spring comes round again this year

And the first meadow-flowers appear.

God knows ’twere better to be deep

Pillowed in silk and scented down,

Where Love throbs out in blissful sleep,

Pulse nigh to pulse, and breath to breath,

Where hushed awakenings are dear...

But I’ve a rendezvous with Death

At midnight in some flaming town,

When Spring trips north again this year,

And I to my pledged word am true,

I shall not fail that rendezvous.

Ink on paper. 22.6 × 18.3 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Poster for the exhibition of the Society of Moscow Women Artists. Print on paper. 75 × 93 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Alexander Levenson printing workshop. Print on paper pasted on fabric. 124 × 93.6 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Moscow, Alexander Levenson fast-printing workshop. Lithograph

Chromo-lithograph on paper. 100 × 70 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Colour print on paper. 37.8 × 56 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Colour print on paper. 37.7 × 55.8 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Lead pencil and watercolour on paper. 30.5 × 21.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Chromo-lithograph on paper. 116 × 70 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Chromo-lithograph on paper. 101 × 71cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Chromo-lithograph on paper. 98 × 70 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas. 69 × 98 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas. 100 × 201.5 cm

© Tretyakov Gallery 1. Patočka, Jan. “Heretical Essays in the Philosophy of History”. Minsk, 2008. P. 148. 2. https://

Detail of monument. Bronze. Moscow

![Unknown artist. It’s All for Victory! Subscribe to the Military 5 1/2 % Loan. [1915–1916]](https://www.tg-m.ru/img/mag/2020/1/art_66_03_13_1.jpg)