Anticipation of Victory. THE ARTISTS REMEMBER

Sergei Tkachev

In the winter of 1942 Sergei Tkachev was badly wounded in the shoulder. “I came under fire, a direct target,” he would remember. “I was running from side to side, this way and that, but a German bullet caught me in the shoulder. My sleeve was all red, my white glove staining with blood. An officer ran in my direction. ‘Wounded, are you?’ he asked. At that point I burst into tears. It was my right arm - how was I to become an artist now?” In the thick of combat, pinned down by enemy fire, this young soldier had only one thing on his mind, cherished only one dream - of returning home and becoming an artist!

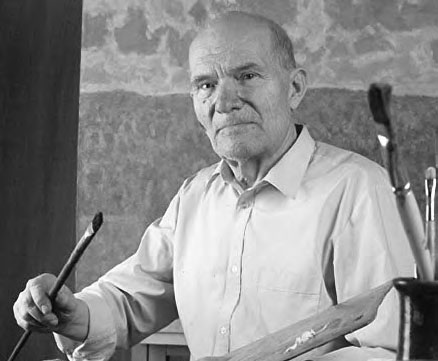

Yefrem Zverkov

An artist would often make decisions that would prove crucial for the future at moments of extreme difficulty. On one particular bright sunny day in May 1942 a squadron of the 301st Rifle Division was under heavy mortar shelling. At a moment when its seemingly endless roar subsided, Private Yefrem Zverkov was standing on the pitted soil amidst his dead comrades, his hair turned grey. “If I am to be spared death, I shall paint a beautiful flourishing Earth, a world filled with great calm,” he pledged.

Boris Nemensky

Boris Nemensky, who fought all the way to Berlin, would recall the events that led to his creating his painting “Mother”: “We had taken a village, and put up for the night in some woman’s hut. ‘You left us to the Germans, and now we’ve got to feed you,’ she kept complaining. Sometime after midnight I woke up to see that my sleeping comrade’s greatcoat had slipped off him, and the woman was covering him with a blanket. And she washed our footwraps too. You see, we were kith and kin to her! We understood then that, for us, she was another mother.

Later she said, ‘And my young ‘uns are off with the army too, maybe someone’s out there giving them the same kind of welcome...’ Before we left, we brought her in a whole stove load of firewood. We did what we could for her. Because she was a mother to us.”

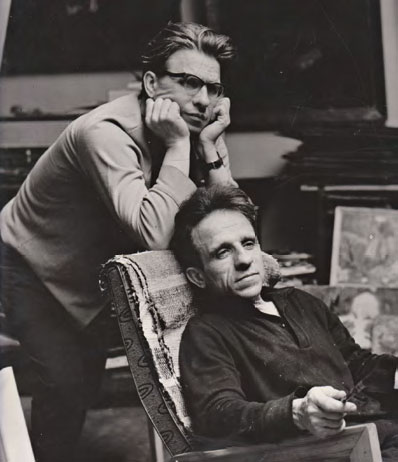

Viktor Tsigal. 1943-1944

Battlefield photograph

Vladimir Tsigal after a landing operation in Malaya Zemlya

Battlefield photograph, 1943

Viktor and Vladimir Tsigal

The battlefield images of the Tsigal artist brothers were created close to the frontline, often in direct line of fire, and offer a very special documentary record of the Great Patriotic War.

It was in 1942, while returning from Samarkand to Moscow, that Viktor Tsigal enlisted in a Volunteer Armoured Corps that was being formed in Sverdlovsk, joining its political department as a visual artist. “And off I went from Moscow on armoured vehicles and camions - across Russia, across Europe, across different fronts, for two and a half years,” he recalled. “Then, in 1945, I published in Sverdlovsk a collection of battlefield images ‘Combat Heroes of the 10th Volunteer Armoured Corps’ and made it my graduation work at the [Surikov] institute in Moscow.”

His brother Vladimir’s experience as a soldier was honed in direct proximity to conflict. “Life on the battlefield is like a convoluted and complex labyrinth,” he remembered. “Where is the space, between the bursts of machine gun fire and the deadly shrapnel, in which you can stay alive only if you don’t make that one extra step to the side, forward or backward - the step that will prove to be fatal?"

In his 1986 autobiography, Vladimir Tsigal described an astonishing episode aboard a mine-sweeper carrying wounded soldiers from Novorossiysk's burning assault lines to Gelendzhik - as if in a dream, a torpedo passed them by, very narrowly missing the ship. “And I beheld death. It slipped past us as a dark shadow. Infinitely long and dark death. All together we were saying, looking back at the sea: ‘It passed, it almost touched the vessel! A narrow miss!’”

Grigory Yastrebenetsky

Grigory Yastrebenetsky recalled the Leningrad premiere of Dmitry Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony (the “Leningrad”) at the Large Hall of the Philharmonia on August 9 1942: “My mother had bought tickets for the concert at the Philharmonia. I was on leave then and we happened to attend the first performance in Leningrad of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7. Sometimes now it’s said that there were orders to chase away any enemy aircraft for the duration of the concert. Actually, I don’t think that was true - there were quite enough problems as it was. I wouldn’t say the hall was packed. There were empty seats on a small divan next to us. No long ovation, either - it was just a concert, but a very good one! When it was drawing to a close, an air raid began, its sounds heard in the auditorium. But the musicians carried on to the end. Then mother and I walked out of the Philharmonia, and I picked up from the ground fragments of hot metal left by the air raid. Had I been aware of the historical importance of the moment, I would probably have kept one as a souvenir.”

Grigory Ushaev

Grigory Ushaev remembered how he learnt about the end of the war, about Victory. “I think it was the eighth of May. We were stationed at the time in Konigsberg. In the small hours of the morning, as the day was beginning to break, I was woken by the sound of terrible firing. Nothing out of the normal, but I jumped up - I’m a light sleeper. I grabbed my pistol and ran out into the street. And I saw our soldiers standing there, firing into the air. What astonished me was that they were doing this without saying anything. They were just firing in the air, not a word. Later I would create a work dedicated to that moment.”

The exhibition “Anticipation of Victory” at the Russian Academy of Fine Arts is devoted to the 75 th anniversary of Victory in the Great Patriotic War, an expression of profound respect and gratitude to those who, at the cost of their own lives, defended their homeland. It was they who made Victory possible.

The editors thank the Information Department of the Russian Academy of Arts and particularly Elena Klembo for assistance in bringing together this material.