Repin as the Mirror of the "People’s Will". REFLECTIONS OF THE "NARODNAYA VOLYA" MOVEMENT IN THE ARTIST’S WORKS

Ilya Repin was keenly sensitive to the reformist context of his time, and reflected the political nuances of Russian society in a number of his most important paintings, most significantly “They Did Not Expect Him”. Particularly revealing are those works associated with the “Narodnaya Volya”, or “People’s Will” organization, which was an integral part of the much wider sociopolitical “Narodnik” movement - from narod, “the people” - of the 1870s-1890s.

To understand the “Narodnik” movement in Russia, it is important to consider it as much more than a particular stage of the Russian Revolution, or even a social philosophy. It does not fit into the confines of any rigid theory - not only because it was never ideologically homogenous, but also because it was defined by a particular mood, a kind of spiritual tendency, that took over a wide section of the educated classes. Proponents of “communal socialism" believed that, historically, Russia was developing in the same direction as Europe; however, it would bypass capitalism with its “ulcer of proletarianism", and achieve a just social order by drawing upon the traditions of peasant communal life. Thus, the duty of the “educated minority" was to pay the poor masses of the people back for the labour and suffering that had provided for the privileged life that some in society enjoyed.

Some thought that improving the efficiency of everyday labour, and building schools and hospitals would pave the road to salvation, while followers of the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin believed in the purgative fire of “universal rebellion", which would work a transformation with the “instinctively socialist" Russian peasants and lead the nation to a new way of life. Those not convinced by Bakunin's assertion that the masses were ripe for social rebellion supported Pyotr Lavrov, a prominent philosopher, publicist and narodnik, who urged the educated elites to engage in a systematic effort of propaganda.

By the end of the 1870s, however, it had become clear that the Russian peasantry was not susceptible to such revolutionary exhortations. Occasionally, peasants and industrial workers would even hand rabble-rousing socialists over to the authorities, as they had ample reason to believe that listening to such agitators would get them into trouble.

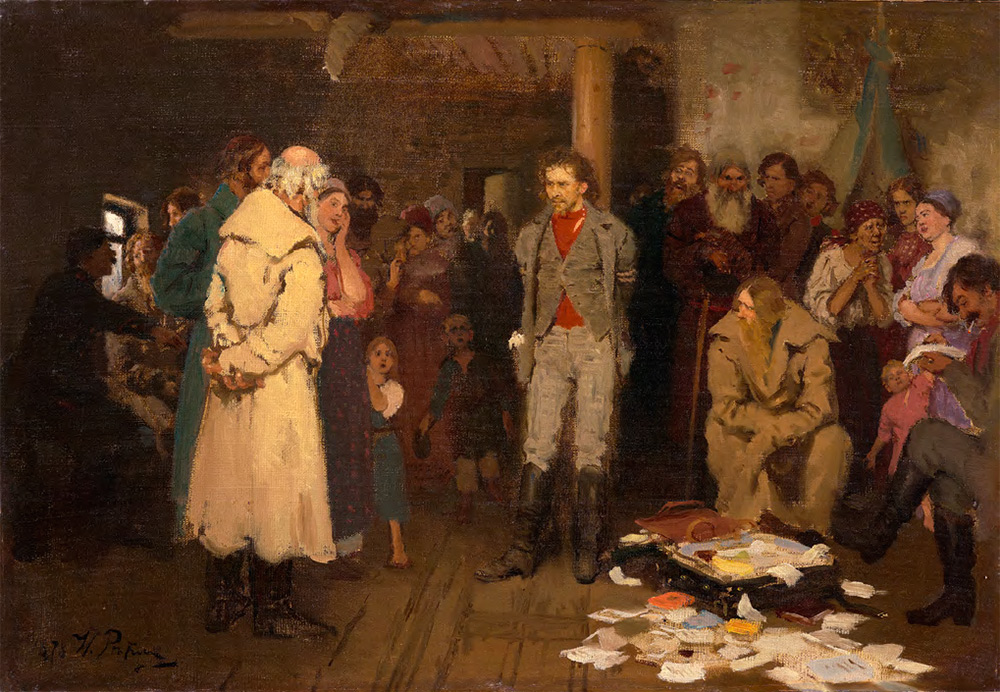

The scene in Repin's “Arrest of a Propagandist" (18801889, 1892, Tretyakov Gallery) is significant in exactly that context. The propagandist has apparently been betrayed not by a police informant but rather by a peasant - the agitator's rebellious rhetoric has left the peasant cold, his calls to action baffling. The revolutionary stares furiously at a dark figure in the left-hand middle ground. Who is he looking at - a Judas? Repin himself said that the traitor was the man sitting on the bench. The other people in the painting appear either indifferent or hostile, reacting to the arrest in the same way as the crowd that surrounded the figure of the propagandist in the first version of the painting, where he is depicted tied to a post (1878, Tretyakov Gallery). The chasm between the people and the “educated classes" was widening, magnifying the tragic split that would eventually lead to the emergence of revolutionary terrorism.

Ilya REPIN. Arrest of a Propagandist. 1878

First version of the painting with the same title (1880-1889, 1892, Tretyakov Gallery)

Oil on canvas. 38 × 57 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

“Arrest of a Propagandist" was Repin's last painting on the subject of the “Narodnik" movement. Essentially, the work is about the narodniks’ loss of hope, which was one of the reasons that many of them came to embrace the political terrorism of “Narodnaya Volya". The artist, sensitive to the events that unfolded around him, began working on this painting in 1880, possibly in response to a very high-profile mass trial, the so-called “Trial of the 193", which took place in 1878.

Investigations into anti-government propaganda were conducted in 26 governorates and led to the detention of thousands of suspects, of whom 193 were tried by the Special Court of the Ruling Senate. It became clear after the trial that 90 of those defendants, in the words of the prosecutor Vladislav Zhelekhovsky, were brought before the court “to create a background context", only to spend the best years of their lives in preliminary confinement “for nothing". From those 90 individuals, 80 were soon sent into exile under police surveillance, according to the standard practice in cases where there was no formally defined crime - it was, after all, impossible to convict for intention alone. However, the government believed it was both possible and advisable to administer punishment for just that.

Indeed, arrest faced both those who implored the peasants to action - to “pick up their axes" and rebel - and those who “went to the people" to explore the situation on the ground, “on reconnaissance". Some wanted to test themselves, to prove that they were worthy of the lofty calling and capable of serving the downtrodden, and existing in challenging living conditions, while others were ashamed of enjoying their comfortable life while the masses of their countrymen and -women lived in abject poverty. Some, under the guise of a carpenter or a shoemaker, engaged in revolutionary propaganda; others just followed the spirit of the time.

An entire generation was infected with the rebellious ideas that inevitably led to the tragic events which ended with the “Trial of the 193". It is worth noting that the future heroes of the “Narodnaya Volya" revolutionary movement had belonged to this generation of “Narodnichestvo" (peasant populism), and it was at their hands that Emperor Alexander II would die on March 1 1881. For a long time Alexander Mikhailov, one of the organization's leaders, lived among a community of Old Believers in Saratov. Sofia Perovskaya, who played an important role in planning the Tsar's assassination, had previously worked as a smallpox vaccination nurse in the Saratov Governorate. On August 4 1878, Sergei Kravchinsky (also known as Stepnyak-Kravchinsky) stabbed to death General Nikolai Mezentsev, Russia's Chief of Police, in broad daylight on a crowded street; five years before that dramatic event, Kravchinsky had been engaged in propaganda while disguised as a woodcutter. In 1877, the future fiery revolutionary leader Vera Figner, after leaving the University of Zurich to dedicate herself to bettering the lives of the Russian peasants, went to live and work as a nurse in the village of Studenitsy in the Saratov Governorate. Figner was one of those who strove to do real work to improve the bleak lives of real people, even if only by a little. Those who stayed that course would later be called proponents of “small deeds", whereas Figner went on to become an icon of the revolutionary “Narodnaya Volya".

The question has often been asked why these revolutionaries could not simply live normal lives - nothing prevented them from gaining an education and finding meaningful work; they could teach or practice medicine, or find a similar occupation. The answer is, unfortunately, quite clear: in the Russian Empire it was all too easy to be considered a dangerous rebel. If an individual chose true service to the people over blinkered obedience to authority, and let their conscience guide them rather than following expectations and custom, even staying within the confines of the law could not save them from being labelled “enemies of public order".

It seems very likely that such had been the fate of the young man who features in Repin's most famous painting of this series, “They Did Not Expect Him" (18841888, Tretyakov Gallery). The work was first shown at the 12th “Peredvizhnik" (Wanderers) exhibition in 1884; despite its obvious narrative subject, the painting did not provoke objections from the censors. Some critics called the work “An Exile Returns to His Family", and such an interpretation does indeed seem correct. Although scholars often refer to the young man in the painting as a member of the revolutionary “Narodnaya Volya", he is probably a more moderate narodnik. It is hard to imagine a member of a terrorist organization being released from exile: the coronation of Alexander III in May 1883 brought no amnesty for political prisoners, and an escaped convict would not have come to his family's home.

Furthermore, although he is clearly unexpected, the young man does not appear out of place among his family: much about their shared cultural background is revealed by the interior of the room, with its portraits of the poets Taras Shevchenko and Nikolai Nekrasov (both beloved by the progressive Russian intelligentsia), and the engraving of “Golgotha", from Charles de Steuben's very popular painting. Even the barely discernable image of Alexander II on his deathbed does not seem out of place here - not all the narodniks, even those who were unfairly penalized by the government, or members of their families, believed that Alexander II, the “Tsar-Liberator" who had emancipated the serfs, had deserved assassination.

Ilya REPIN. “They Did Not Expect Him”. 1884-1888

Oil on canvas. 160.5 × 167.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Members of “Narodnaya Volya" represented a tiny fraction of the nation-wide “Narodnik" movement. Nevertheless, Repin's painting depicted a story that could be found rather widely in Russia at this time, and which was also popular with other contemporary artists. Thus, the fate of the young people depicted in Nikolai Yaroshenko's “The Student" (1881, Tretyakov Gallery) and “The Girl-Student" (1883, Kaluga Museum of Fine Art) could easily end up close to that of Repin's character. Vladimir Makovsky's “Social Gathering" (1875-1897, Tretyakov Gallery) echoes Repin's “Secret Meeting" (1883, Tretyakov Gallery; Repin called it by the less revolutionary title, “In the Lamplight"), and both paintings introduce the viewer to the many types of the Russian intelligentsia, drawn as they were from different social backgrounds. The political situation in Russia at the time was such that many protagonists of this kind might find themselves behind bars just for attending such a “social gathering", one that the authorities could easily interpret as a “secret meeting" of revolutionaries.

Interpretations of the characters in Repin's “They Did Not Expect Him" most frequently suggest that the young man has returned home to his mother, his wife (who is sitting at the piano) and two children. It is significant that the older child, a boy, seems very happy, while the little girl frowns

apprehensively - it is likely that she does not remember at all this man who had disappeared from her life when she was so young. This writer's suggestion is that the young man is not in fact a husband and father, but rather a brother and uncle. At this time, men and women dedicated themselves to the revolutionary struggle at a very early stage in their lives, usually when they were still students. In such circles, those over the age of 25 could be perceived as old, and for anyone who had a family, and especially children, such responsibilities would make them think very carefully before they abandoned everything for revolutionary ideals.

Repin worked very hard on the main figure in “They Did Not Expect Him". In one version, it was actually a young woman (the portrait of Alexander II on the wall is missing in that variant). The artist made repeated changes to the head and face, for the last time in 1888, after Pavel Tretyakov had already purchased the canvas. In that final version, there seems to be a question in the young man's eyes: how will he be received at home? Can his choices in life have been justified? This is no fanatical revolutionary, one who remains steadfast in his beliefs - everything about him speaks of doubt. “Uncertainty" seems to me to be the key word in understanding this painting.

The family's reaction to the young man's return, like society's reaction to the revolutionaries, particularly the most radical among them - everything involved such uncertainty. Many were in two minds about the terrorist tactics of “Narodnaya Volya", especially after the tragic events of March 1 1881. (Repin himself had witnessed the execution of those members of the organization whose actions had resulted in the death of the “Tsar-Liberator".) On the one hand, those revolutionaries were heroes; on the other, murderers. But what had pushed them to murder, what had driven them towards terrorism?

The authorities failed to appreciate the peaceful and constructive opportunities that the narodniks and their efforts brought to the country's rural population. Russia's repressive government saw potential rebellion everywhere, and consequently even more young people were drawn into the ranks of the opposition. It is possible that “Under Police Escort. A Muddy Road" (1876, Tretyakov Gallery), Repin's first painting on the topic, was a reaction to such “repressions disproportionate to the crimes concerned".[1] After all, the campaign of “going to the people", “Narodnichestvo", and the mass arrests that followed both reached a peak in 1874-75.

Ilya REPIN. Under Police Escort. A Muddy Road. 1876

Oil on canvas. 27.2 × 53.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

With no guarantees of civil rights, many felt they had no protection from the government and thus resorted to protest involving force. On January 24 1878, an otherwise unremarkable young woman, Vera Zasulich, came to the reception room of the Governor of St. Petersburg, Fyodor Trepov, and shot her handgun at the venerable general. Her gesture was a response to the flogging that the general had ordered as punishment for the political prisoner Alexei Bogolyubov, who was under arrest when he failed to greet Trepov with the mandatory gesture of respect.

Zasulich stood trial and was acquitted by the jury. An adoring crowd of young supporters was waiting for her as she left the court, thus protecting her from being sent into administrative exile. Paradoxically, in that particular historical context such an action could be seen as a way of upholding the law.

Since this political climate made it impossible to conduct effective socialist propaganda, the goal of changing the form of government and establishing constitutional rights - in other words, political struggle - inevitably became a priority. Without the support of the population, political struggle could only be conducted in the form of terrorism, which was the most “effective" way to “utilize miniscule revolutionary resources".[2] Radical ideas emerged within the larger “Narodnik" movement, giving rise to spontaneous terrorist activity, and the demand to make that course the guiding principle of revolutionary struggle grew. Such were the circumstances that gave rise to the appearance of “Narodnaya Volya" in 1879.

It was a time when anyone engaged in political terrorism could expect to die for their ideals. Repin created a portrait of someone like that in his painting “Before Confession" (1879-1885), which he titled simply “Confession"; in 1936, reflecting the character of those new times, its title was changed to “Refusing Confession".

Ilya REPIN. Before Confession. 1879-1885

Oil on canvas. 48 × 59 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Repin was inspired to paint this work by Nikolai Minsky's poem “Last Confession", and eventually, since censorship made the painting's exhibition impossible, the artist gave it to Minsky. The poem was published in 1879 in the first issue of the underground “Narodnaya Volya" magazine. Fulfilling a role as the organization's publication, “Narodnaya Volya" did not want to be in opposition to Russian society, and the magazine was intended to create a favourable impression of the revolutionaries and their actions among the public.

It was Repin's friend, the art critic and historian Vladimir Stasov who brought the magazine “Narodnaya Volya" to the artist: he had found the illegal publication in the postal delivery box of the National Library, where he was working at the time. Dedicated to executed revolutionaries, Minsky's poem appeared alongside the last letter of the revolutionary Solomon Wittenberg, whose execution was announced in the same issue.

The revolutionary credo approved individual acts of political terrorism and regarded them as the ultimate self-sacrifice. Stepnyak-Kravchinsky, after his successful assassination of Mezentsev, fled Russia and became a writer. His novel “Andrei Kozhukhov" described the terrorist's state of mind before attempting an assassination as an all-consuming “egotism of self-sacrifice" of one destined to die: Kravchinsky certainly knew the feeling at firsthand.

Semyon Frank, the renowned philosopher and researcher of the ethics of the radical intelligentsia, has noted how revolutionaries, in sacrificing their own lives on the altar of the wellbeing of humanity, “do not hesitate to sacrifice others, too", whom they saw as either innocent martyrs or accomplices of the evil of the world order. Revolutionaries envisaged their fight against the latter as their “most immediate goal and the main method of realizing their ideals". As Frank wrote in his 1907 study “Vekhi" (Landmarks), “This is how intense devotion to the future of humanity gives rise to a fierce loathing of living people, and the longing for Heaven on Earth becomes a passion for destruction."[3]

In the early years of his reforms, the young Alexander II had once noted: “There is much goodness and true nobility in the character of our young people today, and Russia should expect a great deal from them if they are given the right direction; if that does not happen, the very opposite will follow."4 History has shown clearly how the “direction" chosen by that youthful generation could find no common ground with the course taken by the Russian monarchy.

- Shcherbakova, Ye.I. “’The Misfits’. The Road to Terrorism. 1860s-1880s.” Moscow, 2008. P. 111.

- Ibid. P. 116.

- Frank, Semyon. ‘The Ethics of Nihilism' // “Vekhi (Landmarks): A Collection of Essays on the Russian Intelligentsia". Moscow, 1990. Pp. 166-167.

- “The Revolutionary Movement in the 1860s". Moscow, 1932. P. 45.

Tretyakov Gallery. Detail

Tretyakov Gallery. Detail

Oil on panel. 34.8 × 54.6 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas. 104.3 × 175.2 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Graphite pencil, stump, whitewash on brown paper. 9 × 17 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Graphite pencil on paper. 24.8 × 16.6 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Drawing for the initial concept of the painting “They Did Not Expect Him” (1884-1888, Tretyakov Gallery). Graphite pencil, stump on grey paper. 29.6 × 21.7 cm

© Russian Museum

Oil on canvas. 108.5 × 145.6 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas. 88.8 × 62.3 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas. 131 × 81 cm.

© Kaluga Museum of Fine Art

Oil on panel. 23.4 × 14 cm

© Russian Museum

Sketch of the first version (1883-1898, Tretyakov Gallery) of the painting “They Did Not Expect Him”. Pencil on paper. 31.4 × 19.9 cm

© Rostov Regional Museum of Fine Arts

Sketch for the painting “They Did Not Expect Him”. Graphite pencil on paper. 36.8 × 26.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Original version of the painting with the same title (1884-1888, Tretyakov Gallery). Oil on panel. 45.8 × 37.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Preliminary drawings for the painting “They Did Not Expect Him”. Graphite pencil and stump on paper. 27.4 х 22.7 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Study of the face for the painting “They Did Not Expect Him” (1884-1888, Tretyakov Gallery). Pencil on paper. 30.8 × 23.4 cm

© Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki

Pencil on paper. 29.9 × 21.7 cm

© Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki

Sketch of the head of the returning exile for the painting “They Did Not Expect Him”. Oil on canvas. 40.5 × 35 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Oil on canvas mounted on cardboard. 36.5 × 26 cm

© Nesterov Bashkir Art Museum, Ufa

Pencil on paper. 31 × 23.5 cm

© Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki

Sketch for the painting “They Did Not Expect Him”. Graphite pencil on paper. 30.8 × 23.4 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Version made before the correction of the head of the man entering the room. Pencil, stump on paper. 24.5 × 27.5 cm

© Radishchev Art Museum, Saratov

Photograph by Sergei Levitsky