Alexei Yavlensky in Siberia

Alexei Georgievich Yavlensky (1864-1941) gained world-wide recognition for his vital visual energy and the sense of intense spirituality and colour of his paintings. Russian by origin, and a figure with unbreakable cultural ties with the country, Yavlensky entered the circle of masters associated with the beginnings of the European avant-garde.

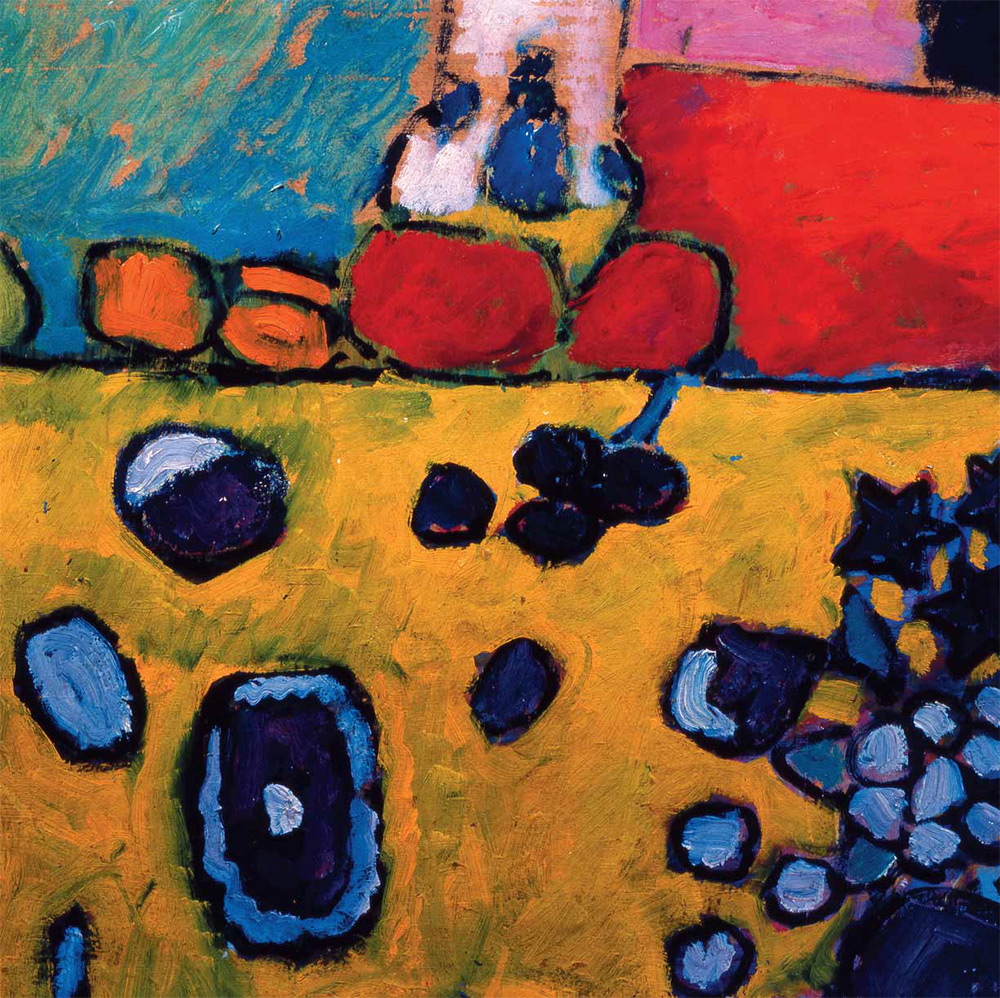

Still-Life with Garish Table Cloth. 1909. Detail

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum

Alexei Georgievich Yavlensky (1864-1941) gained world-wide recognition for his vital visual energy and the sense of intense spirituality and colour of his paintings. Russian by origin, and a figure with unbreakable cultural ties with the country, Yavlensky entered the circle of masters associated with the beginnings of the European avant-garde.

A graduate of Moscow's Military College, Yavlensky studied at St. Petersburg's Academy of Arts, before travelling to Munich in 1896 to continue his studies at the Aschbe school; in Germany he also became known as von Jawlensky. While in Germany and Switzerland he became acquainted with works of both classical and contemporary art; the outbreak of World War I and resulting political developments in Russia forced him into emigration. In Europe Yavlensky became a famous artist, enjoying real success with both art critics and the public alike.

Only his "motherland" remained indifferent to him. His art was ignored and his name forgotten, a phenomenon that can be partly explained by the fact that all his artistic heritage is abroad. Russian museums and private collections have no more than 25 of his works, half of them in the Siberian city of Omsk. They are mostly works dating from the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, allowing for an appraisal of Yavlensky's creative development - from academic portraits, to post-impressionist and fauvist landscapes and still lifes.

The question of how Yavlensky's works reached Omsk, given that the artist himself never visited Siberia, is fascinating. In the summer of 1891, when he was a student of the Academy of Arts, Yavlensky travelled to the Southern Urals with his friend Grigory Yartsev, to make some "plein-air" studies. But neither then, nor later, did Yavlensky travel as far as Omsk. Coincidentally, his Munich acquaintance David Burlyuk - another explorer of new directions in art - came to Omsk in 1919 where he arranged the parties - he called them "grandiausars" - and organized an avant-garde exhibition which had considerable local impact.

Could he have brought Yavlensky's paintings with him? The answer must be negative, since the Omsk museum collection is chronologically diverse, collected over twenty years before it "settled" in Omsk; furthermore, some self-portraits and portraits of the artist's brothers indicate that this collection must have belonged to one of Alexei Yavlensky's relatives. All available evidence suggests that the collection is in some way connected with Yavlensky's brother, Dmitry (1866-1920 ?)[1].

Following his departure for Germany Yavlensky met his brother Dmitry on a number of occasions. In 1898 he visited Yaroslavl gubernia (province) where Dmitry was working as a county-clerk in Romanov-Borisoglebsk. Evidently it was then that the artist painted Dmitry's portrait - until recently registered as the "Portrait of an Unknown Man in Grey". Again, there is no doubt that Alexei Yavlensky met his brother in St. Petersburg in 1906, where the artist had come to participate in an exhibition organized by Diaghilev; at that time Dmitry was working in the Internal Affairs Ministry. Yavlensky participated in a number of other exhibitions in St. Petersburg, sending his pictures from Munich[2]. Perhaps Dmitry collected his brother's works after the exhibitions had ended, and in such a way a collection of Yavlensky's pictures gradually accumulated in Dmitry Yavlensky's St. Petersburg apartment.

At the end of 1913 Dmitry Yavlensky accepted a position as Governor-General of the Steppe region. Moving to Omsk, he may have brought his collection of Yavlensky's works with him. Rapid career changes were typical for the prewar and war time, and from that date the fate of Dmitry Yavlensky was closely connected with the collection. In September 1915 he was appointed as Governor of the Akmolinsk region, not far from Omsk, and three months later he became Governor of Pskov and later of Mogilev, both regions in the west of the then-Tsarist Russian empire. It is easy to imagine the mess of such hasty preparations for departures: perhaps, indeed, the collection was left in Omsk, given that the Yavlensky family probably intended to return there. The Revolution and subsequent Civil War clearly complicated their plans and hopes.

In November 1919 the Red Army conquered Omsk and at the beginning of 1920 local Communist officials began preparations for opening the Omsk KhudProm (arts and crafts college, named after Mikhail Vrubel), with a connected museum. It is likely that at that time. Yavlensky's works were taken - expropriated - to the museum (no inventories have been found).

In 1930 the college was closed, with part of its collection transferred to the art department of the Western-Siberian Regional Museum, which later (in 1940) was transformed into the Fine Arts Museum.[3] According to records, Yavlensky's works were at first exhibited in the Museum, but were soon sent into storage:[4] they were not listed in the museum catalogues of the 1940s and 1950s. It was only at the beginning of the 1980s that these works became the object of special attention, with accompanying first steps undertaken to investigate their origin.

Simultaneously, three paintings, the "Portrait of an Unknown Man", the "Portrait of a Military Man with a Cigarette" and the "Portrait of an Unknown Man in Grey" - all transferred from KhudProm in 1932 and attributed to "an unknown artist of Valentin Serov's circle" - were targeted for research.

Establishing the identity of the young man - the sitter in the "Portrait of an Unknown Man" - was the most important investigative task. The composition of the portrait - the sitter's head three- quarters turned, and his gaze apparently reflected in a mirror - hinted that the work might be a self-portrait. However, comparison of the portrait with other selfportraits from different collections of the late 19th and early 20th centuries produced no results. Experts from the major Russian museums could provide no attributions. In this case the solution of the problem came from nothing less than constant communication with the portrait itself! The opportunity of hanging a work of art - in this case the "Portrait of an Unknown Man" - on the wall of the room of the museum's fund keeper is a rare privilege indeed.

The image of the subject revealed itself in a book on the "Der Blaue Reiter" (The Blue Rider) movement; it contained a self-portrait of Alexei Yavlensky painted in 1914 from a private collection in Bern. It was only reasonable to suppose that the author of the other portraits - that "unknown artist of Serov's circle" - was also Alexei Yavlensky. This suggestion was confirmed by descendants of the artist from Lucerne, Switzerland; the Omsk portraits were finally included in the complete annotated artist's inventory (Catalogue Raisonne).[5]

The authors of the catalogue fixed the name of the sitter in the "Portrait of a Military Man with a Cigarette" (c.1893) as another of the artist's brothers, Sergei. The portrait may have been painted in St. Petersburg, where Sergei Yavlensky studied at the Military Juridicial Academy. The free manner of its brush strokes, its dark colours with contrasting light effects, and energetic relief modeling of form reveal the work of a genuine disciple of Ilya Repin, confirming Alexei Yavlensky as a true follower of the old masters. Perhaps it is no accident that Ilya Repin, in jest, used to call Alexei Yavlensky a "Velazquezlad", quite the young Velazquez.

For a further period the identity of the sitter of the "Portrait of a Man in Grey" remained unclear, until, in 1999, Dmitry Yavlensky's grand-daughter entered the investigation. Her family archive included a photograph of her grandfather from the period of his service in Yaroslavl. Close comparison between the portrait and photograph proved that the sitter was indeed Dmitry Yavlensky.

While in Germany Alexei Yavlensky experienced the influence of contemporary artists, especially the great impact of Vincent van Gogh which can be evidently seen in Yavlensky's landscapes of 19051906 from the south of Bavaria ("La Montagne" (The Mountain), "The Street"). His separated brush strokes and contrasting complementary colours manage to depict the energetic movement of natural forces. Yavlensky's admiration for Matisse and other fauvists was vividly expressed in the "Still Life with Garish Table Cloth" (1909), a painting characterized by its flat compositional decision, simplified forms and loud clear colours.

One of the first students of the Omsk KhudProm College told the author of this article that at the beginning of the 1920s Yavlensky's paintings decorated the walls of the college library, and that there were many more pictures than are now in the Museum. Such memories inspired hope for future discoveries which recently became real, with their location in the Soviet period painting collection of the Omsk museum. The discovery took place at a meeting of the funds' commission in February 2002 where works of art from the reserve collect-ion were carefully examined. Their revelations were a source of real joy for all present; for this critic, the major object of interest was a rather small still-life, a bunch of yellow Spring flowers in a white- blue vase. Its wide, free brush strokes, fresh bright green, the water in the cup, light blue and pink flashes on the background, and the darkened edge of the cardboard seemed so familiar... No doubt it was a Yavlensky. The fact that this still-life had been in the Omsk KhudProm College where in the 1930s the whole collection of Yavlensky's works was kept provided additional supporting evidence.[6] In the course of further investigat-ions Yavlensky's still- life was carefully compared to the etalon Yavlensky's works and a stylistic analysis carried out; the results convinced the attribution board that it was indeed a Yavlensky.

Archival documents of 1954 stated that the "Still-life with Yellow Flowers" was on a list of works of art "to be written off and transferred to other cultural institutions". In such a way, the still-life should have been hung on the walls of a theatre; luckily this decision was never to be realized. 30 years later the still-life was placed in storage in the subsidiary fund of Soviet- era art. This sunny still-life "lived" in a file behind the shelf for another 20 years.

The fate of the Yavlensky Omsk collection is so much like the fate of the artist, whose name was forgotten in Russia for many decades. This small part of the artistic heritage of this outstanding master, preserved in Siberia, gives a fortuitous opportunity to determine his place in the history of Russian culture, and to form a true notion of the development of Russian art at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

- The State Archive of the Omsk Region. re: for details see the corresponding note in Russian

- In the 1900s Yavlensky participated in the following St. Petersburg exhibitions: the "New Society of Artists" (1905), the "World of Art" (1906), the Forth Exhibition of the "Union of Russian Artists" (1906-1907), "Garland" (1908), "Salon" (1909), "Salon" of Vladimir Izdebsky (1910).

- In the process of the investigations into the Omsk Yavlenskys it turned out that there are some works that could be connected to the KhudProm collection. This refers to a study for the self-portrait with a portrait of Elena Neznakomova on the reverse side - a work from the visual art collection of the Omsk Historical-Regional Museum. In 1940 when the art department was transferred to an independent institution, the "Self-portrait" was still not registered in the file with the works of some other artists, and was in the storage of the regional Museum. It was registered in 1990 only.

- "The Vase with Flowers and Fruit" (oil on cardboard, 62x47) was in the collection. In 1968 it was given to a Moscow private collection in exchange for "A landscape" of Martiros Sarayan.

- Re: Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky, Angelica Jawlensky. Alexej von Jawlensky. "Catalogue Raisonne of the Oil Paintings.Vol. 1: 1890-1914". London-Munich-Mainland-New York, 1991.

- In framing, the lower part of the still-life is cut off - therefore, the author's signature is probably lost.

Oil on canvas. 71 by 57.5 cm

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum

Oil on cardboard. 48 by 62 cm

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum

Private Archive (Moscow)

Oil on canvas. 71 by 58 cm

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum

Oil on canvas. 74 by 50 cm

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum

Oil on cardboard. 48 by 67.5 cm

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum

Oil, Tempera on cardboard. 41.5 by 33.3 cm

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum

Oil on cardboard. 61.5 by 47.5 cm

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum

Oil on cardboard. 33.8 by 67.7 cm

The Vrubel Omsk Art Museum