Shanghai Museum. SELFLESS COMMITMENT TO SOCIETY

The Shanghai Museum was inaugurated in 1952 on the site of the former racecourse building located at 325 West Nanjing Road, and in 1959 moved into the Zhonghui Building located at 16 South Henan Road. Following the advances of the decades and the accompanying evolution of society, construction of the Museum’s new building started at the People’s Square in the city centre in August 1993, under the auspices of the Shanghai city government. At the end of 1995, the Galleries of Chinese Ancient Bronze, Ceramics, and Sculpture opened on a trial basis. The new Shanghai Museum in its completed form was officially opened to the public on 12 October 1996.

Shanghai Museum at night

The new museum building has a total floor area of 39,200 square metres; its height is 29.5 metres. Its giant circular roof and square base, symbolizing patterns of Heaven and Earth respectively, create an extraordinary visual effect. The entire building is an elegant fusion of elements of traditional culture with a reflection of contemporary China. As a large-scale modern museum of Chinese ancient arts, Shanghai Museum has a heritage collection of more than one million items, including 140,000 precious cultural relics across 21 categories including bronzes, ceramics, calligraphy, paintings, jade, ivory, bamboo lacquer, wood lacquer, oracle bones, seals, and ethnic minority crafts. The Museum’s most distinguished collections are in its bronzes, ceramics, calligraphy and painting sections. The new museum has 11 galleries and three exhibition halls, which stage periodic loan exhibitions from Chinese or foreign museums and institutions.

Bronzeware is one of the most prominent ancient arts and crafts forms of China, and is unrivalled by any other ancient civilization for the richness of its forms, decorative motifs, inscriptions, and brilliant casting technology. It is believed that the Chinese Bronze Age began in the 18th century BCE and evolved through the historically recorded dynasties for about 1,500 years. During this period, bronzes were designed as implements for the ruling elite to use in rituals of worship, feasting, and on other ceremonial occasions. The type and quantity of bronze vessels used by the nobility had to correspond to the owner’s place in society and status. Important events from their own or their families’ history were often inscribed on them, thus preserving a large amount of precious historical information. Shanghai Museum’s collection of ancient Chinese bronzes is one of the richest in the world, containing nearly 7,000 works, covering various types of implements and many different eras. The collection impresses for its huge quantity of exhibits and the skill of their execution: together it comprehensively demonstrates the historical development of ancient Chinese bronze art from the 18th to the 7th century BCE. This group of museum pieces are national treasures, complete with a wealth of inscriptions and other such marks of distinguished provenance, which records their past ownership. Among them, the famous “Da Ke Ding” is one of the most prized items of Shanghai Museum.

Shanghai Museum has a wide variety of ceramic works, ranging from Neolithic hand-moulded ware and wheel-thrown ware made from terracotta, grey pottery and black pottery, through to painted porcelain with rich decorative patterns. Many items have both artistic and historical value. Especially important are the painted pottery pieces, many of which are particularly rich in design. The pottery of both the Songze and Liangzhu Cultures, unearthed in the Shanghai area, reflects the technological level of pottery firing in pre-historic times in the region.

The major part of Shanghai Museum’s Chinese porcelain collection consists of treasures handed down from antiquity, and it is justifiably famous both at home and abroad. It includes items that are emblematic of Chinese porcelain, which illustrate the historical development of the form. Among the proto-celadons of the Shang and Zhou periods, and celadons dated to the Han, Wei, Six Dynasties, and Sui and Tang periods, there are remarkable works that are characteristic of their time. From the Yuan dynasty onwards, porcelain from the area of Jingdezhen has outshone work produced in other areas. Many technological varieties of underglaze and monochrome glaze, such as the coating of blue-and-white porcelain and porcelain decorated in underglaze red, have been successfully fused to the body in the firing process. Jingdezhen became the country’s main base for porcelain manufacturing, and Shanghai Museum holds a comprehensive range of its porcelain ware, produced with exquisite workmanship during the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties - especially those last two periods - much of which is extremely rare. Among these are many blue-and-white porcelain pieces of outstanding quality, as well as wares decorated with enamels produced during the Yuan dynasty, and porcelain produced by an imperial kiln during the Hongwu (1368-1398), Yongle (1403-1424), Xuande (1426-1435) and Chenghua (1465-1487) eras of the Ming dynasty and in the late Ming dynasty. In addition, among the large number of works made in the Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong (1662-1795) eras of the Qing dynasty are masterpieces that reflect the true characteristics of their periods. Porcelain wares produced at Jingdezhen during the Ming and Qing dynasties constitute the most important part of the Museum’s collection.

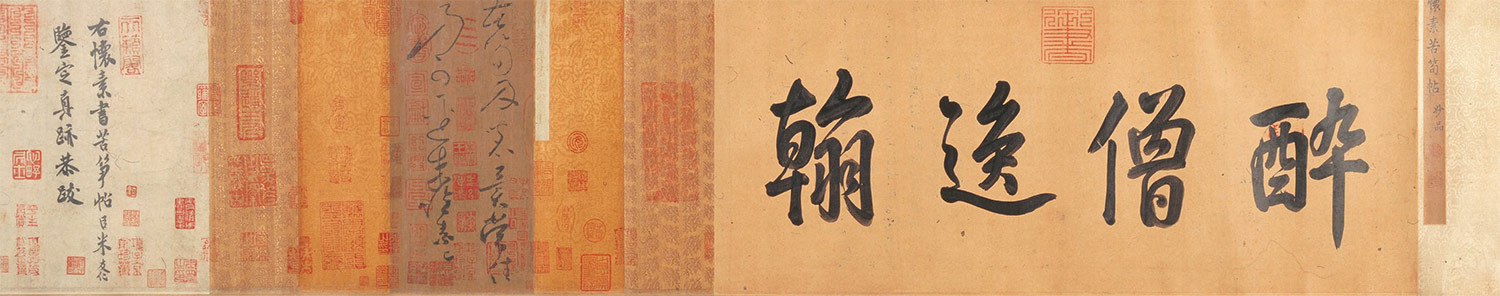

Bitter Bamboo Shoot Note.

Model Scroll in Cursive Script. Silk scroll. Huai Su, Tang Dynasty (618-907). Length: 25.1 cm

Shanghai Museum holds an extensive collection of calligraphy, including many ancient masterpieces by famous artists. Among pieces renowned in the history of ancient Chinese calligraphy are “The Letter from Shangyu in Running Script” by Wang Xizhi and “Note on a Duck-Head Pill in Semi-cursive Script” by Wang Xianzhi of the Eastern Jin dynasty; “Note on a Duck-Head Pill in Cursive Script” by Huai Su of the Tang dynasty; “Multi-View Pavilion Poetry Book in Running Script” by Mi Fu and “Letter of Reply to Xie Minshi in Running Script” by Su Shi of the Northern Song dynasty; “Autumn Meditation Poetry Scroll in Running Script” by Zhao Menfu of the Yuan dynasty; and “First and Second Odes on the Red Cliff Scroll in Cursive Script” by Zhu Yunming of the Ming dynasty.

There are also many exclusive works by renowned calligraphers, like “Thousand Character Classic Scroll in Cursive Script” by Gao Xian of the Tang dynasty. Surviving works by this master, a senior monk highly skilled in writing cursive script in the mid-Tang dynasty, are extremely rare, making this work of great research importance. In terms of quantity and quality alike, Shanghai Museum’s collection of calligraphic works produced during the Ming and Qing dynasties is comparable with its painting collection. They complement each other well, and together present a complete panorama of Chinese painting and calligraphy as it evolved during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

China was one of first states to develop lacquer, producing items for various purposes. A red-lacquer wood bowl unearthed at the Hemudu Neolithic Site in Yuyao, Zhejiang province dates back about seven thousand years. The first peak of lacquerware production came during the Spring and Autumn period, the Warring States period, and continued on through the Qin and Han dynasties. It saw lacquerware production appearing in many locations, with an accompanying increase in varieties of form, while lacquer was used more widely than in previous times. Because of significant improvements in technology, lacquerware production was classified as a professional job. After the Han dynasty, lacquerware gradually developed from articles for daily use into sophisticated artworks, and many new types emerged. Thus, the industrial art of lacquer-making, including burnishing to expose engraved gold or silver (jinyfn ping tuo), inlaying lacquer with mother-of-pearl, and carved lacquer, evolved during the Tang and Song dynasties. Lacquer techniques gradually improved in the Yuan dynasty and many noteworthy achievements were made, as a number of renowned experts emerged. The Ming and Qing dynasties were a golden age of lacquer production, achieving unprecedented heights in terms of both production quantity and variety, with combined varieties of lacquer techniques developed by masters of the form. Lacquerware-making received imperial attention and encouragement. Official and private lacquer workshops co-existed and developed in parallel, and the two directions both influenced and learned from one another.

Although furniture may be usually intended for everyday use, Chinese lacquered furniture can be imbued with the connotations of classical aesthetics in its shapes, lines and decorative motifs, showing the deep charms of Eastern culture. Ancient Chinese furniture, as a medium of both lifestyle and ideas, conveys a sense of the customs and ritual systems, as well as the aesthetic tastes of antiquity. It stands out for its distinctive artistic features. The literati and elegant scholars of the Ming dynasty paid great attention to furniture design and interior furnishing. They combined their aesthetic points of particular charm and interest with artisans’ virtuosity, utilizing yellow rosewood and red sandalwood among other precious materials: their hardness, elegant colours and gorgeous textures enhance both ornamental and artistic appeal. As a result, the Ming dynasty saw the appearance of a number of masterpieces. Furniture-makers and cabinetmakers of the Qing dynasty focused on its dimensions and exquisite ornamentation, and artisans became skilled at carving. They often used a variety of materials and an approach that combined multiple techniques to create furniture in magnificent styles that was popular at court and among high society. Shanghai Museum’s collections of Ming and Qing furniture produced in those dynasties consist of museum pieces, donated by the collectors Wang Shixiang and Chen Mengjia, which demonstrate the simple, unadorned literati style of the Ming, and the exquisite carvings of the Qing dynasties.

Other categories of heritage collections include fields such as coins, ancient jade, imperial seals, and carving: they are of considerable scale and contain numerous famous artefacts, with some including complete series of objects. The Museum’s collections of cultural relics of the country’s ethnic minorities (which are rarely shown in a general art museum) reveal its openness to new and different directions, as well as the breadth of its interests. Acquisition of most of these artefacts was made possible by the provision of funds from the state. Some works returned to their homeland from collectors overseas, while others, formerly in private collections, have been donated to the Museum. A small part of the relics came as a result of exchange with associated museums, while there are also articles obtained from archaeological excavations. Many such items show traces of their rich histories, including the varied events that they have witnessed.

Since the opening of its new building, Shanghai Museum, as one of the most important institutions in the region, has arranged several exhibitions to show to the public art treasures that represent the cultural achievements of humanity, as part of series of thematic programmes such as “Civilizations of the World,” “Relics from China’s Remote Provinces and Provinces with Rich Collections of Artefacts,” and “Treasures of Chinese and Foreign Art”. The Museum has organized exhibitions that generated great resonance among viewers, such as “Star of the North - Catherine the Great and the Golden Age of Russian Empire”, “Splendours of Smalt - Art of Yuan Blue-and-White Porcelain”, “Barbizon through Impressionism: Great French Paintings from the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute”, “Faberge: Legacy of Imperial Russia”, and “The Armoury Treasury of the Russian Sovereigns”.

In China’s cultural world, Shanghai Museum has always been a leader in foreign cultural exchange, and has conducted exchanges with foreign museums and cultural institutions from the 1980s onwards. The first cultural exchange office of China’s museum sector was established in 1985, dedicated to serving the cause of international cultural exchange at Shanghai Museum. Over more than 30 years, the Museum has facilitated over 130 loan exhibitions outside China, which have toured Asia, Europe, North and South America, Oceania, and another 27 countries and regions. Most of the exhibitions were staged after the completion of the new museum in 1995. Shanghai Museum, through its rich, exquisite collections, organized these loan exhibitions to interpret and demonstrate Chinese culture in its breadth and profundity.

Shanghai Museum has established lasting and amicable co-operation with many famous museums and institutions around the world, deepening and expanding cultural exchange. Since the 1990s, Shanghai Museum has signed memoranda of co-operation with well-known institutions such as Tokyo National Museum, the British Museum, the State Hermitage Museum, the Berlin State Museums and other entities, involving research, work on collections, archaeology, education, exhibition-planning, heritage conservation, and photography of artefacts, among other fields.

Shanghai Museum has also been very active in academic exchanges. Along with various types of temporary exhibitions, the Museum often holds high-level international conferences on various subjects, inviting foreign experts and scholars for in-depth exchanges on exhibition themes and content, and to promote the development of related disciplines. It held two high-profile international Museum Leaders Forum in 2012 and 2015 respectively, and invited the world's top museum officials to those meetings, including curators from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, the State Hermitage Museum, the Tokyo National Museum, the Musee du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, and other institutions. This kind of high-level dialogue between international museums is of great significance to the Museum’s business expansion and exchange work with Chinese and foreign museums. Shanghai Museum successfully organized and hosted the “22nd General Conference & 25th General Assembly of the International Council of Museums” at Shanghai World Expo Exhibition & Convention Centre, held 7-12 November 2010. This was not only the largest international conference in the history of Chinese museums, but also the first time that the General Conference of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) had been held in China since its inception in 1946. Shanghai Museum, which was involved throughout the conference, not only enhanced its reputation and status in the international museum community, but has also since expanded its spaces for international cultural exchange.

Shanghai Museum’s public education service also stands out in the Chinese cultural and museum sectors. Regular educational activities consist of guided tours, educational readings, public lectures, master classes on the applied arts, cultural excursions, screening of documentary films, theatrical performances, thematic tours, exhibitions and workshops, volunteer activities, activities for the Museum’s friends, and education aimed at younger generations. The Museum, through such activities, carries out a wide variety of levels of education from different perspectives for viewers and visitors, in order to meet the cultural demands of different audiences. At the same time, it takes advantage of developments in digitization and network platforms to implement some of its educational programs, which is playing a pioneering role in the museum community in China. It organizes nearly 200 sessions of academic lectures for the general public each year, which has become a trademark programme among Shanghai Museum’s educational activities. In addition, there are a series of educational activities tailored to different groups such as children and young people. All such activities are extremely popular with audiences.

Shanghai Museum has been a pioneer among China’s museums in the conservation and restoration of cultural heritage; it established a heritage restoration workshop and a conservation laboratory in 1958 and 1960, respectively. Since 1987, it has assumed responsibility for the mission of the Shanghai Test Laboratory for Conservation Science of the Ministry of Culture of The People’s Republic of China. In 1989, the academic journal “Sciences of Conservation and Archaeology” was founded. In 2005, the Museum became Key Scientific Research Base of Museum Environment, State Administration for Cultural Heritage of The People’s Republic of China, and the Qualification Unit for the Restoration of Movable Cultural Relics. In 2015, after the renovation of a 9,142-square-metre space, a seven-storey laboratory was completed, integrating the conservation and restoration resources of Shanghai Museum into the Shanghai Museum Conservation Centre (SMCC). The Centre, under the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, supports the missions of operating a key research base for innovative research and of editing and publishing academic journals, in addition to heritage conservation, heritage restoration, scientific and technological archaeology, and research and application on the ancient crafts.

It has 24 conservation scientists and 16 conservation technicians, and is equipped with a range of advanced scientific research and restoration equipment. It strives to integrate modern technology with the traditional methods of painting, calligraphy, bronze, and ceramics restoration, in order to enhance the capabilities of research and innovation and to improve techniques of heritage conservation. In addition, it carries out international academic exchange activities: in 2016, for example, it offered assistance to St. Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum in restoring the ancient Chinese calligraphy and paintings on silk from its collection.

Shanghai Museum is the only entity that has qualified leaders of archaeological excavation teams in Shanghai city. The Archaeology Department of Shanghai Museum, established in 1956, is responsible for archaeological fieldwork and research in the Shanghai region. Archaeological work in Shanghai began in the 1930s, and over the past 80 years, 32 ancient cultural sites have been discovered in the city. Among them, four sites have been declared to be of national cultural heritage, with 11 sites under the historical relic protection programme at the municipal level of Shanghai city. The Songze, Guangfulin and Maqiao relic sites are not only national cultural heritage, but also locations at which prehistoric archaeological cultures were first defined, and from which they received their names.

Shanghai Museum has carried out orderly surveys and excavations at these sites. It initially constructed a chronological framework for covering the period starting from Majiabang culture, through Songze, Liangzhu, Guangfulin and Maqiao culture, to the Zhou dynasty, forming three pillars of archaeological research in the Shanghai region: Fuquanshan and the origins of Chinese civilization, and the study on the progress of Liangzhu civilization; cultural pursuits of early settlers in Guangfulin and Shanghai; and Maqiao and interrelations between human survival and changes in the natural environment. Among them, the Guangfulin archaeological project at the Songjiang district of Shanghai city won the Archaeological Field Work Award at the first China Archaeological Conference. As well as such excavations of early civilizations, archaeological discoveries at the Qinglong Town site corroborated that the area was once a major hub on the Maritime Silk Route during the Tang and Song dynasties, providing new evidence for the study of the Maritime Silk Route. The Yuan Sluice site at Zhidanyuan, with the ruins of the country's largest hydraulic engineering system (built in the Yuan dynasty) so far discovered, was chosen as one of 2006 “Top Ten Archaeological Discoveries in China”.

In order to better fulfil Shanghai Museum’s unique role in the promotion of history and culture, exhibition and education work, and to improve the public appreciation of art and cultural awareness, Shanghai Museum is planning to build an additional East Building (with a space of about 100,000 square metres) in the Pudong district; construction is expected to begin in 2017. The East Building of Shanghai Museum will showcase ancient Chinese culture and integrate multiple disciplines of the arts, with particular emphasis on the collections of painting and crafts. The West Building exhibition plans will correspond with the Museum’s bronze- and ceramic-focused thematic display of ancient Chinese arts, to form an overall pattern of “one museum with two wings, linking the East and the West, to distinguish and to complement one another, and to match harmoniously”. To be in tune with the development of the times, Shanghai Museum must respond with expanding further the functions of research, educational experience, social services and cultural exchanges, and among other fields, play a better role in the modern system of public cultural provision.

Shanghai Museum aims to follow a non-profit principle to serve society and its development with its social function as a museum collection, including research and educational activity. It strives to maintain its status as “a leading museum in the country, and a first-rate museum in the world”, to become the world’s premier museum for collections centred on ancient Chinese art.

Shanghai Museum, exterior

Height: 23.5 cm

Diameter: 45 cm

Height: 93.1 cm

Height: 39.5 cm

Height: 44.4 cm

Height: 26.1 cm

Diameter: 45 cm

Height: 24 cm

Length: 26.1 cm

Length: 45.2 cm

31.2 x 53.1 cm

Height: 10.3 cm

Diameter: 31.3 cm

Diameter: 5.6 cm

Height: 66.7 cm

Height: 23.7 cm

Height: 112 cm

Height: 119.5 cm/div>

Height: 101 cm

Height: 25 cm